While most of us were busy unwrapping gifts this Christmas and getting merry, a war was brewing. No, we’re not referring to the unfortunate slide towards global conflict, but instead of a far more entertaining, and thankfully less destructive war: the volley of dubs exchanged between Dot Rotten, Wiley, Jaykae and Stormzy. What began as a shot at Coventry-bred rapper JAY1 over a debt has rapidly expanded into a multi-directional spate of one-liners and chest puffing, as some of grime’s biggest names took to Twitter and the studio to air out grievances and claim supremacy. For die-hard fans of the genre, it’s an opportunity to see their heroes showcase their skills and to debate who really is the best. But for outsiders, it can be confusing.

The passion for verbal sparring in grime has always been among the culture’s most confounding aspects for non-initiates, right up there with reloads. For some, the sights and sounds of young, black and (usually) male artists aggressively cussing each other out in a series of boasts, threats and punchlines represent everything menacing and frightening about it. And while undoubtedly xenophobic and ignorant, let’s be extremely generous for a moment and admit that out of context, a grime clash can sound like the run-up to physical confrontations. But as any grime head will tell you, clashing is so much more than that. And to be honest, grime without war dubs would just be boring. Lyrical war is a fundamental component of the genre, one with a long and distinguished musical history.

Grime just wouldn’t be grime without clashing.

First, forget the notion that heated competition in black music is a new idea: jazz musicians in Harlem took part in “cutting contests” to prove their chops against rival players as early as the 1920s. More famously, reggae and dancehall soundsystems (from the 1960s to now) have long engaged in heated duels for supremacy—competing in terms of loudness, selection, and verbal jousting. This format has even been appropriated by Red Bull for their branded Culture Clash series. In many ways, these dancehall clashes served as the foundation for grime’s own verbal competition, with just a hint of US battle rap (celebrated in the movie 8 Mile) thrown into the mix. Unlike its predecessors, however, grime’s competitive spirit has proven resistant to being boxed into a single format. Perhaps because the scene came of age from 2000-2010, a time of rapid change in the music industry, the parameters for a clash have shifted every few years.

Before grime had even landed a genre tag, UK garage collectives like Pay As U Go and Heartless Crew were dueling live on stage at clubs like Destiny in Watford. At this early stage, the format was closest to dancehall clashes at events like Sting and Sunsplash in Jamaica, with patois-heavy bars over a DJ’s selection and hype mattering more than disses. This was the template for clashes at later events like Eskimo Dance, which often turned into impromptu competitions when rival emcees began trading bars on stage.

By the time venues were pressured to blacklist grime in the mid-to-late 2000s, the genre had expanded from a variant of garage to a full-fledged musical revolution, leveraging pirate radio’s local broadcasting as an alternate venue to spread the music (and war) to the masses. Every week, stations like Deja Vu and Rinse hosted shows by rival emcees and crews, which would turn into (occasionally impromptu) clashes. Wiley vs Lethal B and Crazy Titch vs Dizzee Rascal at Deja are all legendary clashes, and excellent examples of the form.

View this video on YouTube

Unfortunately, illegal radio stations turned out to be risky venues for clashing, given their illegal nature, with both Deja and Rinse eventually instituting temporary bans on live emceeing, after a few, shall we say, unfortunate incidents. And I point out the conflict that came from pirate radio clashes not to provide ammunition to grime’s detractors, but to show just how energetic, engaging and real clashes could be—and that fans absolutely loved them. As such, it’s unsurprising that as grime evolved from a youth-led subculture to an entrepreneurship-minded music scene, savvy emcees and DJs would look towards clashes to launch their own brands.

As emcees began focusing their bars on studio cuts rather than live clashes circa 2006, then-Kiss FM DJ Logan Sama compiled the week’s best in his epic War Report segment—and later a best-of CD. Jammer, meanwhile, launched his extremely successful line of Lord Of The Mics DVDs, taking live clashing from radio studios to his basement. At this point, between radio bans, weekly retorts and DVD clashes, the scene became more than a bit saturated with clashes and that enthusiasm for the practice died down with the hype around grime as a whole. And yet grime wouldn’t be grime without clashing.

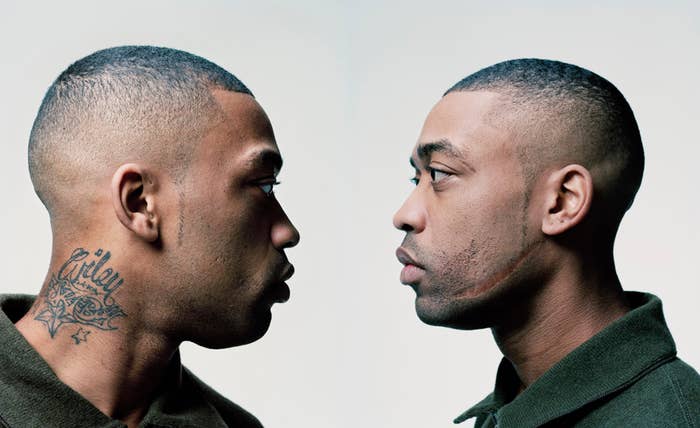

In the mid-to-late 2000s, we saw Skepta and Wiley go at it; Dot Rotten vs Wiley; Dot vs P Money; and Trim vs the world. By 2010, sending had became a part of the art of grime. Even if there was no real-life beef to back it up, emcees used these sparring sessions as a chance to sharpen their own skills.

I’ve always found clashes to be the moment where our favorite mic-men stop caring about mainstream success and focus their attention on the true essence.

When the genre found its second wind in the mid-2010s thanks to social media and streaming, it was a war in September 2013—between producers like Rapid, Preditah, Kahn & Neek, Slackk and more—that captured the attention of underground music media, reminding folk of grime’s energy and even serving as an introduction for newer producers like Inkke and Visionist. Crucially, this war omitted the verbal side of things entirely, with producers trading riddims in the style of dub-soundsytem operators instead. Even producers that opted out of the clashes benefited from the attention: Mr. Mitch, for example, unleashed a series of “Peace” dubs covering grime classics in a wistful, romantic fashion—an approach that later freed him to explore a more personal approach to music.

What is it about clashing that intrigues us so much? Maybe it’s just the natural, competitive spirit (after all, no one asks why footy fans want to see their lads claim a win over a hated adversary). Or maybe it fits into our era of social media drama and conflict? I have always found clashes to be the moment where our favourite MCs stop caring about the mainstream and all its trappings and focus their attention on the true essence: making music for truly dedicated fans, who know the ins and outs of each conflict, while not giving a fig about a crossover hit.