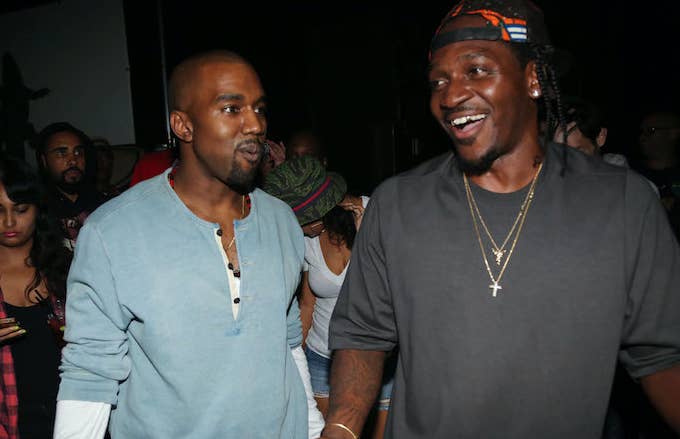

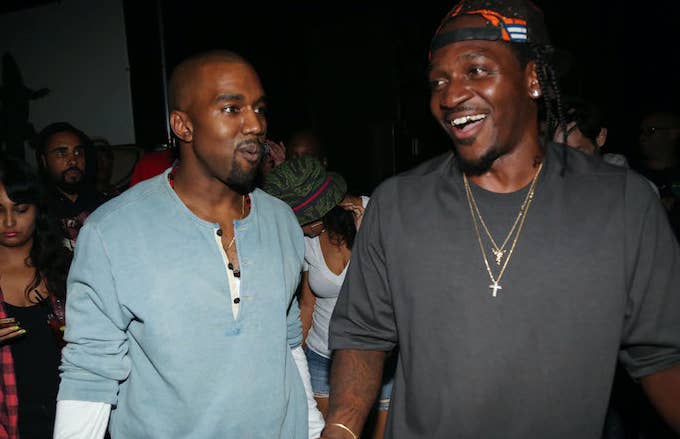

When explaining why he changed his album title from the long-planned King Push to Daytona, Pusha-T talked about “the luxury of time.”

His label boss Kanye West, on the other hand, made the entirety of his new album Ye in less than a month, re-working everything after his disastrous TMZ appearance on May 1. Everything was so last-minute that the album’s cover was literally shot on the way to the listening party.

It’s worth examining how two albums that have so much in common (they’re released by same label, were put out within a week of each other, and were produced by the same person) are, at heart, polar opposites. One is thoughtful, coherent, and detailed, and was in the works literally for years. And one sounds like what it is: something that was thrown together in a few weeks.

An examination of just one track on each record provides enough examples to make this clear. Ye’s opening number, “I Thought About Killing You,” sets the tone for the rest of the record in its inclusion of mistakes. Just about three and a half minutes into the song, Kanye leaves a lyric unfinished, leaving instead a bunch of muttered “um”s [the line in question starts at 3:26]: “Mhm, I don't see no, mhm, yeah, I don't see no, mhm, mhm.”

Just a few seconds before that, at the 3:06 mark, West mispronounces “cache” as “cash-ay” in order to keep the rhyme scheme going. Given Kanye’s history of neologisms (remember the classic “apologin” on "Can’t Tell Me Nothing"?), it might be tempting to believe this is on purpose. But it doesn’t seem purposeful, and there’s nothing elsewhere in the song to indicate that he’s aware that he’s saying the word wrong. Given that elsewhere in the song he didn’t even bother to finish lyrics (and that he now seems to think the height of wit is rhyming “outcome” and “without cum”), it seems safe to assume this is just a mistake.

It’s nearly impossible to imagine Kanye West—a man so obsessed with perfection that he re-worked his entire debut album after it was already finished—leaving a rhyme incomplete or using the wrong word. But there it is: he cares so little about the finished product, or was under so much time pressure, or so convinced that his unfiltered thoughts were genius, that he left literal gibberish on an album.

The lyrics that aren’t gibberish, though, aren’t much better. There’s a line about The Little Rascals—a show that hasn’t had a good joke made about it since Eddie Murphy did it in 1983. There’s an announcement that “I don’t do shit halfway”—a statement which, in this context, comes off as laughable. And the track culminates in the groan-worthy punchline, “Don’t get your tooth chipped like Frito-Lay.”

Pusha-T presents us with the exact opposite approach. Every line is thought out, and every rhyme brings an interesting connection and carries the narrative forward. A close look at “Santeria” reveals this.

The track is in large part about the death of Pusha’s road manager De’Von Pickett, who was killed during a bar fight in 2015. Though Pickett’s name doesn’t show up until near the end of the song, the track’s opening lines make reference to Pusha’s state of mind in the aftermath of the murder:

Now that the tears dry and the pain takes over

Let's talk this payola

You killed God's baby when it wasn't his will

And blood spill, we can't talk this shit over

The very next line quotes Psalm 23, and the religious imagery (Pickett, Pusha explained to Billboard, was “in the church”) continues throughout the verse. The song’s central tension—using words from the religious world to talk about Pusha-T’s very un-Christian wish to violently avenge his friend’s death—builds the whole time, until it culminates in a morbid joke about leaving his enemy in an unmarked grave: “Hey, it’s probably better this way/It’s cheaper when the chaplain prays.”

“Santeria” is certainly not the first time this particular mix of using sacred language to talk about the profane has been used in rap. Jay Z’s 2003 track “Lucifer,” which is about the death that year of Robert “Bobalob” Burke, the brother of Roc-a-fella co-founder Kareem “Biggs” Burke, is another superb example. Push’s spin on the theme belongs in the canon alongside Hov, a rapper who Push respects enough to quotetwice on Daytona.

These opposite approaches to lyricism—the uncorrected first draft versus the carefully considered composition—continue throughout Ye and Daytona, respectively. Over and over again, it’s ill-conceived jokes (“Thought I was gonna run—DMC, huh?”) set against surprising references, multiple meanings, and internal coherence (“Still do the Fred Astaire on a brick/Tap tap, throw the phone if you hear it click.”) It’s predictable puns about Tristan Thompson on one hand, and creative spins on the relationship between the drug game and capitalism on the other.

And ultimately, it’s about Pusha expending the time and effort necessary to cook up something great, while his boss rushed an inferior product out the door.