The novel coronavirus pandemic upended the lives of 55 million kindergarten to 12th-grade students across the country. As their parents confront impossible choices and their friendships are reduced to screens, many are faced with a school experience unlike any in American history. Now, as the summer comes to a close, some students are heading back to classrooms, and not always wearing masks while in attendance. Others will live with virtual learning for at least the first several weeks of the new academic year.

As with everything else in 2020, the start of the school year, combined with a lingering countrywide pandemic, has revealed the politicization of almost every facet of modern American life—all against a backdrop of socioeconomic inequality that seems to threaten the future of millions.

As school administrators were debating how and when to reopen, President Trump, along with Department of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, in July began insisting schools reopen for in-person learning, setting off a firestorm.

“Now that we have witnessed it on a large-scale basis, and firsthand, Virtual Learning has proven to be TERRIBLE compared to In School, or On Campus, Learning. Not even close! Schools must be open in the Fall. If not open, why would the Federal Government give Funding? It won’t!!!” Trump tweeted on July 10.

Democratic Presidential Joe Biden agreed with the need to reopen schools for in-person learning, but on his campaign website lambasted the president for failing to curb the virus’ spread and develop a real plan. After diminishing the spread of the virus he proposed a lengthy list of changes including improvements to distance learning, federal safety guidelines, and emergency funding would help close some of the pre existing and newly formed educational gaps.

After the president’s decree-by-tweet DeVos took to the Sunday morning talk shows to insist that in-person learning was best, while also echoing the president’s not-so-veiled threats that districts that failed to reopen risked losing federal funding.

“By reducing nuanced issues to a simple directive or judgment, she has attached her reputation—and President Trump’s reputation in turn—to those positions, making the issues as polarizing as the two of them,” wrote Jon Valant, a senior fellow with the Brookings Institute think tank.

The Department of Education refuted such claims, and instead, in a statement to the New York Times, accused “Democrats’ operatives, who are fear-mongering and denying the science that says it’s safe and better for kids’ overall health to be back in school.”

Here’s what you need to know about the return to school—and what might be to come.

Where things stand

Political bickering aside, school districts across the country are now facing reality and everything that means during the age of COVID-19 as students in many states began returning to school in mid-August.

Many districts expressed a desire for in-person teaching or some sort of hybrid model at the start of the summer and held onto them as the weeks and months progressed. Yet, as numbers spiked across the country, many had to face reality and began scrambling to distribute laptops to students and train thousands of educators in online teaching software.

Of the 15 largest school districts across the country, 13 decided to start the year with online only classes, according to a CNN report earlier this month. New York City opted into the plan and will start online on Oct. 5, making it 14, with only Hawaii planning to follow a hybrid plan. Teachers and parents across the island-state have been heavily critical of its health department’s failure to produce guidelines for returning to school as principles are being forced to follow their guts.

The health threat

As of Aug. 21, there were more than 172,000 nationwide deaths due to COVID-19 and more than 5.5 million confirmed cases, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A 42-year-old Mississippi middle school teacher and assistant high school football coach died while self-quarantining, refreshing concerns about the threat posed by asymptomatic individuals who might not know they’re infected.

And some of the first school openings earlier this month vividly illustrated the threat of packing students and teachers into classrooms. The Cherokee County School District north of Atlanta told nearly 1,000 students, teachers, and school staff to quarantine after 59 students and staff tested positive following the district’s Aug. 3 reopening. Georgia proved to be an early test case of school reopenings with in-person teaching, and though Gov. Brian Kemp wouldn’t mandate masks, he encouraged them in classrooms while confusingly also filing a now-dropped lawsuit against the city of Atlanta its mask mandate.

Parents in some districts rallied in support of education leaders’ decision to follow suit.

Cherokee public schools spokeswoman Barbara Jacoby told NPR the district “made clear” that “we anticipated positive tests among students and staff could occur, which is why we put a system into place to quickly contact trace, mandate quarantines, notify parents and report cases and quarantines to the entire community.”

Meanwhile, over the weekend of Aug. 15, the district was forced to close its third school since opening, ordering another 500 students to quarantine after 25 tested positive for COVID-19.

The academic threat

Along with the persistent threat to people’s safety and lives, closing in-person classes jeopardizes both short- and long-term academic progress, as well as students’ overall mental health. How well students, families, and school districts will be able to cope with and overcome these challenges largely depends on where they’re located, which, thanks to the property-tax-supported public school system across the country, all but ensures schools in the richest areas have the most resources while those with less get less.

“As it’s done with the country’s health care system, economy, and social safety net, the pandemic is exposing and exacerbating the deep inequities that have long shaped American public education,” according to an Education Week analysis of several surveys of school district administrators.

The Brookings Institute examined multiyear test scores of more than 5 million students nationwide and found that prolonged online learning may put “students may be substantially behind, especially in mathematics.”

Existing disparities in achievement may be exacerbated by new ones that have emerged in technology, with some districts unable to secure enough laptops for students to use from home, while many of those students themselves don’t have sufficient wireless internet access in order to be able to use them. Despite most schools starting the year with online learning, those already strained for resources will find themselves needing to spend more money on cleaning and protective equipment. Funds in the CARES Act, with special consideration given to poorer schools, yet millions of dollars were also funneled to private schools.

The psychological threat

Among one of the most important benefits students attending virtual classes are missing, and that teachers and parents are scrambling to replace, is social and emotional learning. From children in elementary school with stores of unbridled energy that grow larger each day to high-school-aged children who are learning to operate in complex social structures, many teachers and researchers say there’s far more than book learning going on inside classrooms and buildings.

“The disruption to our schools and daily lives has underscored that resilience, relationships, agency, and emotional security are not ‘nice to haves’ in education but rather are foundational to learning and productivity,” wrote researchers from the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning.

Prior to the pandemic, the Learning Policy Institute (LPI) was working to implement social-emotional learning in Minneapolis, Baltimore, and Cleveland. The curriculum spans everything from five-minute breathing exercises to discussions on how to understand and regulate emotions, practice self-care, and for parents how to create supportive home environments. It’s a kind of learning that’s even more important in the midst of a national crisis that has shattered the realities of students, teachers, and their families, according to LPI.

“The COVID-19 pandemic may worsen existing mental health problems and lead to more cases among children and adolescents because of the unique combination of the public health crisis, social isolation, and economic recession,” researchers wrote in an April paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

With parents in many places unable to monitor children’s classroom attendance or performance due to work obligations, much of the onus seems to be put on teachers, who themselves might have children and are being forced to become technologists and psychologists in addition to educators, mentors, and mediators. Many over the summer found themselves with the impossible conundrum of wanting to ensure schools remain closed for safety while also being acutely aware of the harmful effects of the closures on students, and particularly disadvantaged students.

The predicament was too much for some, an EdWeek Research Center survey from early summer found that 10 percent of teachers said they were more likely to leave the classroom than before the pandemic.

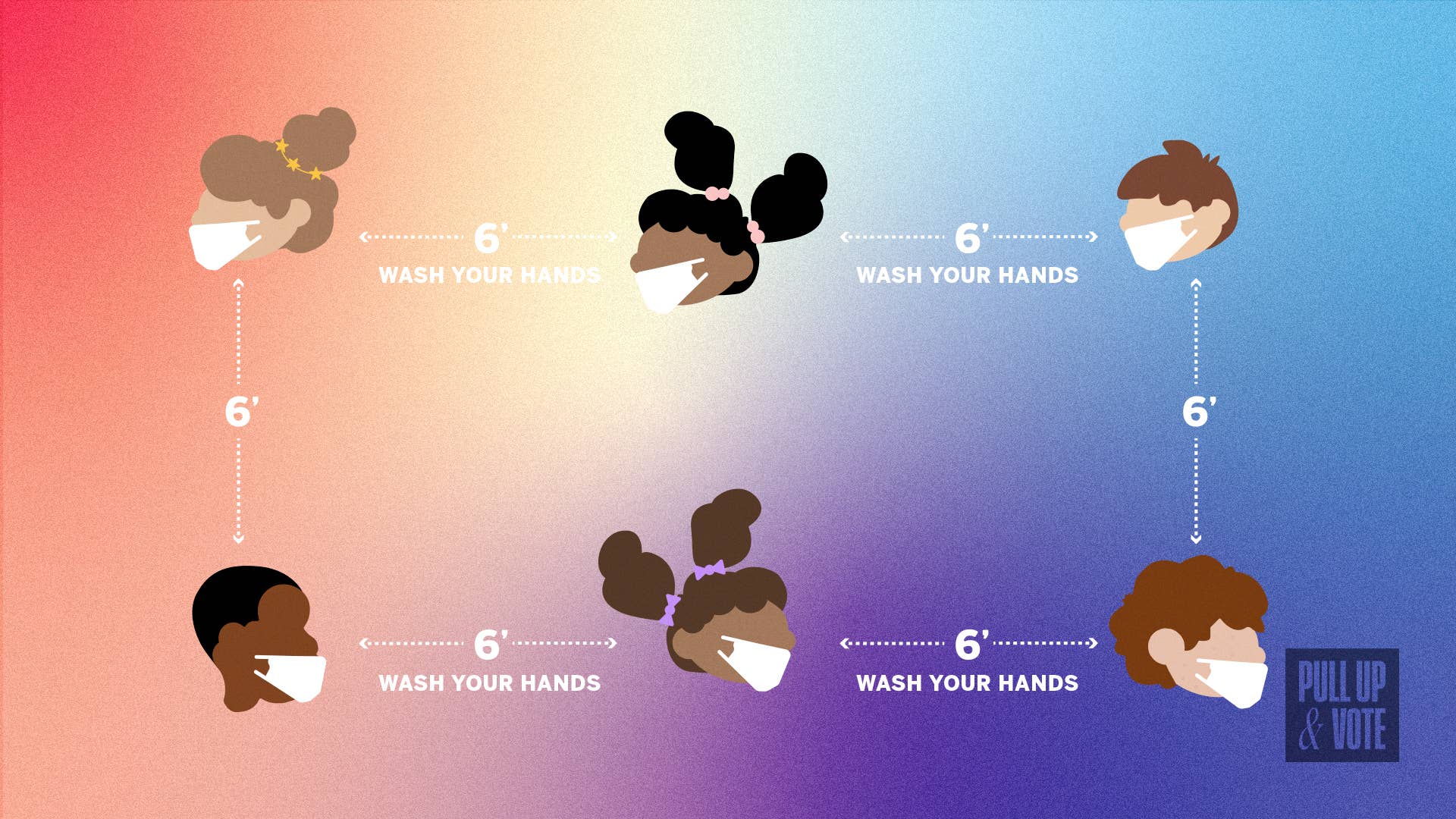

Don’t forget that you can do your part by visiting Complex's Pull Up & Vote site—where you can double-check your registration, register to vote if you haven’t, and request a mail-in ballot.