I was 17 years old when I was first stopped and searched by the police.

Leaving my estate in Camberwell on an early Saturday evening, I had barely reached the bottom of the stairs before being apprehended by a white male and female duo. Stopping me entirely in my tracks, they waffled on about supposed criminal activity going on in the area—car vandalism or something—claiming I fit the description of one of the criminals. In my childlike innocence and confusion, I was cooperative with their demands to search me, which they did abruptly and swiftly. Failing to find what they were looking for, they let me go about my business but, like the first time you ride a bike, or your first kiss, that moment has stayed with me since.

In the wake of the recent murder of George Floyd by police officers in Minneapolis, Minnesota, stark reminders are being handed to black people in America and across the world of what little regard law enforcement have for us; how the cries for justice that followed the deaths of Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Philando Castille and countless other victims of police brutality continue to fall on deaf ears; how, even in Floyd’s desperate cries of I Can’t Breathe in his final moments, the police see us as nothing but disposable. The ensuing protests and riots across the United States have provided ways of releasing the pent-up anger inside the black community towards our systemic oppressors since time immemorial.

Over here in Britain, peaceful protests around the country have shown that the fight for justice for the black community is a global one, and that we recognise the struggle as our own and seek to actively fight it too. This period has also been one of deep personal reflection inward, towards the treatment of black citizens in this country, particularly by the feds. Despite what many white commentators on issues of race relations in England may argue—those who are outraged when Stormzy proclaims Britain is still racist, or when Dave makes a track celebrating black beauty and culture—this country’s hands are not free of blood. They never have been. Though not as overt as in the States, there is an insipid subversion prevalent in the British police system (and wider British life) that targets, terrorises and, on some occasions, kills black people.

Ask your dads, uncles and older cousins about growing up in Babylon, and the pattern of frequent objectification by the police will be telling.

The UK’s racism lies primarily in its age-old societal institutions, the police being a major arm of the discriminatory system. They degrade us when they randomly stop and search us. They target us en masse for violent crimes based on no actual evidence but are seemingly okay with the idea that we look more likely to commit crimes than most other races. They brutalize us for daring to fight for our innocence and rights. Ask your dads, uncles and older cousins about growing up in Babylon, and the pattern of frequent objectification by the police will be telling. When the Met Police launched their ‘stop and search’ initiative in the 1970s, according to Home Office reports, young black men were fifteen times more likely to be arrested than their white counterparts, an overwhelmingly disproportionate number that points to the preconceived prejudices of the police.

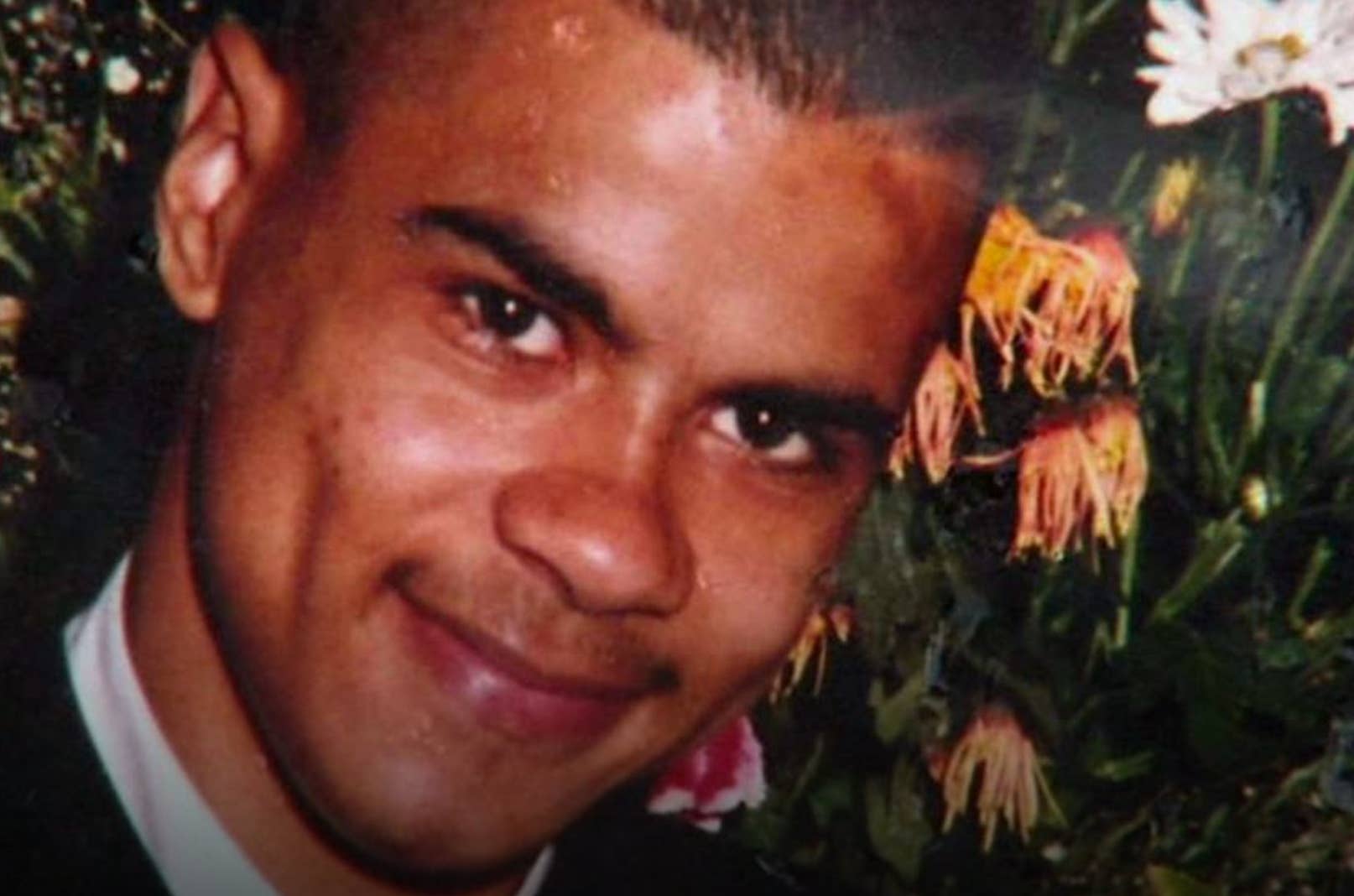

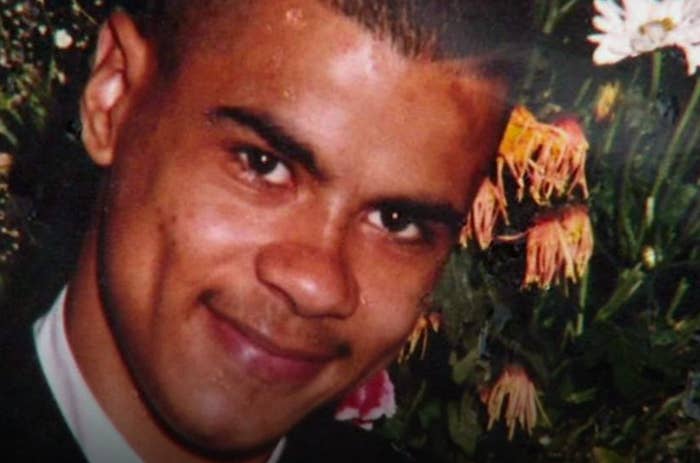

These prejudices dehumanise us to the point where, even as victims of crime, we are treated abhorrently. The 1999 Macpherson Report—concluded six years after Stephen Lawrence’s race-hate murder in 1993—stated that the police’s original investigation of the killing was severely flawed: failing to give first-aid to Lawrence when they reached the scene of his death, failing to follow obvious leads during their investigation, and failing to arrest the suspects. Crucially, the report concluded that the Met was institutionally racist; a conclusion that still rings true today. This institutional racism is a dark cloud over the police in that it convinces them that black people are not afforded the same rights as our white counterparts.

These forces shook the UK music scene to its core in 2011 when legendary reggae star Smiley Culture died after a police raid in his Surrey home. The circumstances of his death—despite the official explanation that a single, self-inflicted stab wound to the heart ended his life—will remain a mystery. Strong suspicions will persist that the police were more involved than they have made out. But what isn’t a mystery is the fact that—once again—the police had failed the wider black community at large and ignored our demands for answers in the wake of Smiley’s passing.

The sight of young black would-be activists uniting in the heart of London under a common cause of justice for black lives in the States is incredibly comforting.

Sheer negligence and a lack of a duty of care towards black people has spilled into direct conflict that has ended too many black lives too early. Just ask the family of Rashan Charles, the 20-year-old killed in Dalston, East London, in 2017 at the hands of the police. Or the family of Edson Da Costa, who died following police restraint in Newham just weeks later. Sean Rigg, Shane Bryant, Sheku Bayoh, Sarah Reed, and countless other examples prove that the police still have much to answer for. The 2011 death of Mark Duggan—who was unarmed and shot dead by police in North London and is very much a cornerstone in this complex modern history—let the black community know nothing had changed from our parents’ days and, even six years after the consequent riots, with the death of Charles, the police were on the same level of crud they’ve always been.

We, the black community in Britain, like our American cousins, find ourselves in a constant struggle against the arm of the state that is supposed to protect and serve us but treat us as second-class citizens when all is said and done. This country is rarely made to look at its own racism head-on. This country hides under its institutions, behind so-called ‘inclusive’ buzzwords such as ‘diversity’ and ‘multiculturalism’, feigned attempts at enacting equality. The powers that be ignore the very real problem of racism until a riot happens and they scramble for integrative solutions that, ultimately, don’t answer our pleas for justice or solve the problem of institutional racism. Events such as the 1981 nationwide riots or the 1976 clash between black youth and the police at the Notting Hill Carnival are just two of countless instances where black youth were made to look like the aggressors, rather than the victims of police confrontation.

The black population’s relationship with British police is fractured as a result, the generational anguish that has been taught to us over decades hardening to an unbreakable exterior of distrust. This violence towards us then trickles down to all walks of life; in education, in employment and in issues of citizenship, as the Windrush Scandal clearly proved. And yet, white Britons are quick to jump on the timeline to say Britain is categorically not racist. The sight of young black would-be activists uniting in the heart of London under a common cause of justice for black lives in the States is incredibly comforting. It shows we have a voice that we will use to combat the genocide of black people.

But we must not lose sight of the transgressions here, at home, that have been prevalent in our own society since the Windrush Gen first stepped foot in Britain in 1948. Understanding this is crucial, to honour those who have lost their lives at the hands of the law and all other forms of oppression, whether physical, emotional or mental. This country has an untold amount to answer for in that regard, and if it weren’t for that fateful night outside of my estate—my first conscious encounter with the racist machine—I probably wouldn’t know just how far the problem goes.