Comedy has always been a problem. Perhaps we just didn’t know about it until recently. Also, those who were aware might have simply not cared.

“Audiences,” those seemingly random masses of people brought together to witness events, have collective desires born out of dark impulses that are never addressed in their “normal” lives, so they often seek some purging or catharsis or vicarious thrill through popular entertainment. Among those forms of entertainment are the ideas and concepts disguised as jokes, sometimes forbidden, of comedians. At first, starting in the depression and then through the Second World War, sanitized mainstream comedy, which used the mediums of radio, movies, and the legitimate stage, tamped down those impulses in order to reach a vast audience by not offending the majority of it. For a long time, this formula worked. There was no offense in any above-ground entertainment. It was safe. It perpetuated the status quo—and lulled the audience into a state of pliant consumerism, as well. And yet it would never be enough to feed the voracious need for distractions to blunt the harshness of reality. That hunger, that insatiable desire—for success, for material, for substance, and the simply capitalistic desire to exploit a product for revenue—expanded the language of mainstream comedy until these more provocative concepts became not only acceptable but expected.

Comedy has always been “ghettoized.” Is that even the right word anymore? There was a time not long ago when there was a Borscht Belt and a Chitlin Circuit. The Borscht Belt, essentially a group of large hotels and bungalow colonies dropped into in the Catskill Mountains of Sullivan County, two hours north of New York City, where Jewish families “from the city” of all economic strata could go for the summer. A place to let the newly urbanized Jews retreat to the rural and rustic and pastoral nature of their collective pasts. But these properties always had a community room, makeshift theater, or nightclub on the premises. This is often where Jewish-American comedians would speak to Jewish-American audiences about life as a Jew in America, in routines replete with Yiddishisms and throwaway insults of other ethnic groups and, because it was such an overwhelmingly male bastion, a steady stream of insults directed at women, too—girlfriends, mothers, daughters, and wives, who served as common reference point punchlines and convenient punching bags that everyone could laugh at knowing that only they would get it and no one else would hear it. These casual insults were good-natured and never delivered with malice or venom or anger but nevertheless casually inculcated the audience into acceptance of these socially acceptable racist and sexist ideas. And, ironically, this seemingly unique brand of comedy became so pervasive it transcended the Jewish experience and became quintessentially American. It became synonymous with modern comedy. So from the end of WWII until the ’60s, when you watched a stand up comedian, whether they were Jewish or not, they were likely employing the style, the form, the structure of routines, the wording of jokes, the stagecraft, the “act,” as it had been pioneered by the Jews. But this was only one great seismic force that created modern comedy, and frankly, if not obviously, in retrospect, it spoke mainly, if not exclusively, to white America.

But perhaps the other greatest force in comedy during this time was African-American comedy. However, like professional sports of the time, African-American comedy could not cross the color line. African-Americans were segregated in all walks of society, and comedy was no different. That’s how the Chitlin Circuit emerged. These were nightclubs across the country that catered to Black audiences that were also hungry to be entertained, have a good time, and laugh but were forbidden from entering all-white venues. Since African-American comics weren’t about to enjoy any mainstream success, on radio, in movies, or on TV, once that medium became established, their routines were relegated to live performances in nightclubs and often recorded for posterity on what were called “party records.”

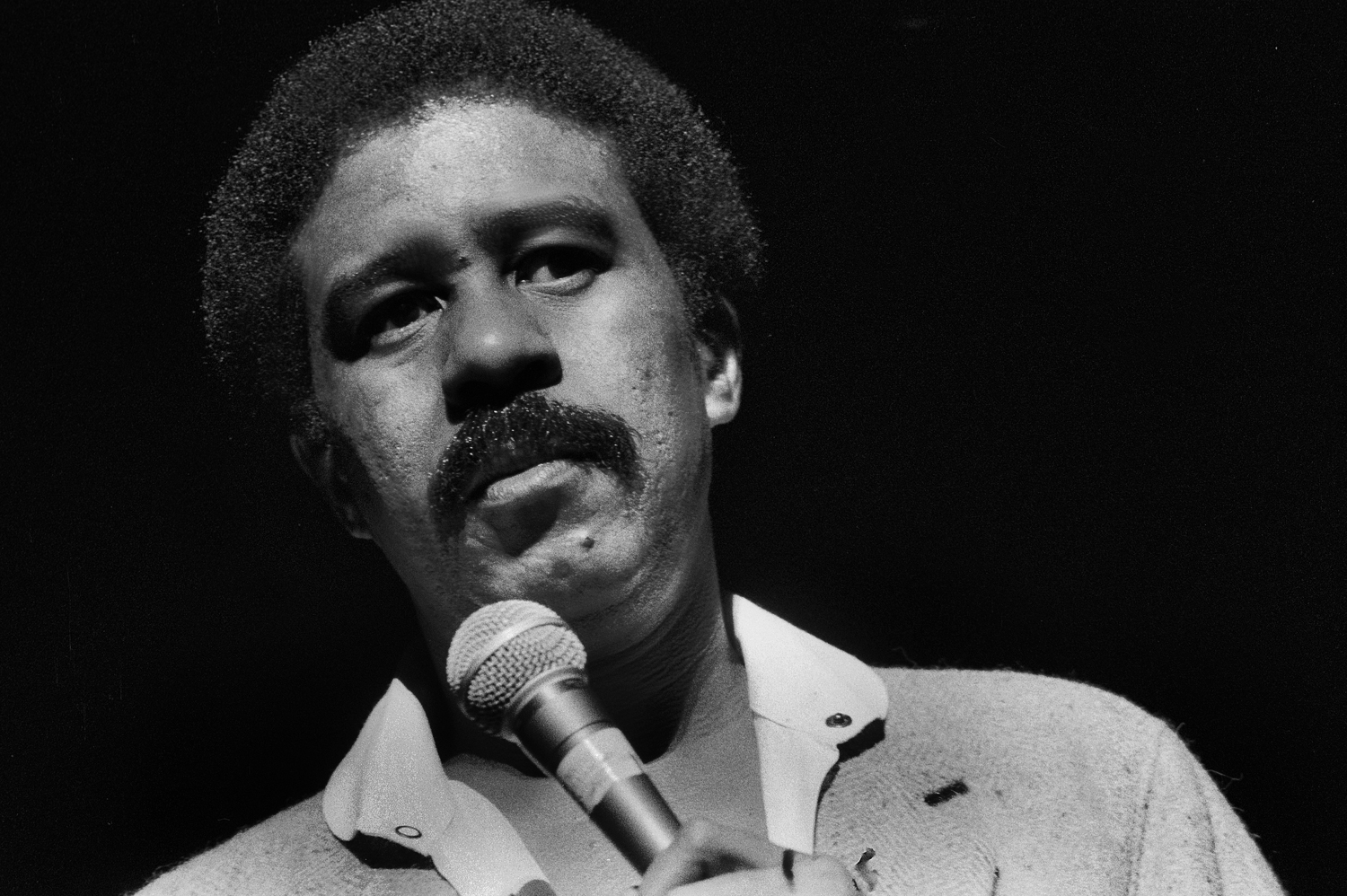

Listening to or watching Richard Pryor was like listening to freedom itself. It was as if Jimi Hendrix did comedy.

But institutional racism preventing Black performers from entering the mainstream of comedy also strangely liberated Black comedy. It allowed ideas and language and experiences to be discussed because there was no fear of fitting into any of the mainstream mediums. So while this comedy began as brazenly honest but often shocking, with crude sexual references and profane language, it evolved into Richard Pryor, who, no less than Genet or Burroughs or Bukowski, spoke with unprecedented originality and honesty and poetry about the underbelly of society and ourselves, only with humor. It was infectious to anyone who was exposed to it. Listening to or watching Richard Pryor was like listening to freedom itself. It was as if Jimi Hendrix did comedy. It was exhilarating and, once heard, could never stop reverberating—so much so that eventually this form of comedy, Pryor’s form of free-associative language and content without any restrictions, became the new mainstream for comedy. But when white comedians, living within the then-acceptable limits of the Jewish-American comedy paradigm, adopted these techniques without deep examination and analysis of the social ramifications, problems began.

This new subject matter was considered extremist in a positive sense in the 1970s. It was now expected across the arts, in movies, music, theater, and certainly stand-up. Shocking. Beyond the pale. Offensive. Graphic. Raw. Explicit. And wildly successful. But never considered racist or sexist or hateful. Or if it was considered so, it may very well have been willfully and actively ignored in the rush to cash in. (Pre-cable television dominated by product advertising remained, with very few exceptions, very white and very safe). Instead, it was sold as new. It was hopeful. It was bold. It was edgy. It was boundary-breaking. It was consciousness-raising. It was conceptual, not ideological. It was thought to be a positive change in the culture. But perhaps most importantly, the market now demanded it. And although it’s just a minuscule period in the history of this culture, like all cultural moments in a capitalist society, those in the midst of it think it will last forever.

So words and ideas that were once forbidden were spoken aloud, and for laughs, onstage. And they were getting them. Where just a few years before, progressive comedians like Woody Allen were purportedly talking about themselves, relationships, and family but really creating carefully crafted fictional personas using uniquely structured jokes as verbal masks, Richard Pryor comes along and talks candidly, without artifice, about his dick and fucking and the fact that his mother was a whore and uses the N-word freely and strikes a chord in American culture. Suddenly the Black underground comedy of the party records meets the beat culture and jazz culture and hippie culture and especially the drug culture and evolves rapidly into the dominant mode of mainstream comedy, and to this day, whether you’re white or Black or any of the many other ethnic groups and genders that have entered stand-up, you are essentially now working from the Richard Pryor African-American paradigm of stand-up, which has replaced the Jewish-American mode of stand up in the same way that Marlon Brando and his raw, spontaneous honesty replaced and left behind the formal falseness of Laurence Olivier and the Shakespearean method as the dominant mode of acting.

But in the accelerated pace of the popular culture, the dialogue quickly coarsens with Sam Kinison and Andrew Dice Clay. Their acts are almost reactionary backlash to the perceived freedoms that society and stand-up were exploring, but using the techniques of this new permissive era and taking them to an extreme that starts to resemble today. They resented, at least in their comic personas, the idea that everyone was equal and we should all get along, as white men who still had dominion over this world but feared it is slipping away. These are early representations of what has flowered into the alt-right, white supremacy, and rampant, even violent, misogyny. They used hate language for laughs, big laughs, and pushed that boundary again. And because it was almost immediately met with mass approval and acceptance, there was never a moment of reflection or pause or examination of the ethics and responsibility and especially the consequences of their acts. Even a pioneer like George Carlin, who carved out his own niche among the many forces of comedy and navigated his way deftly through the decades as a singular voice, was forced—influenced by Kinison, particularly—to abandon his playful but subversive and complex use of language and ideas and adopt a much more blunt, bilious, bellicose, enraged, vulgar, and misanthropic style in his later years.

Yes, the liberation and discovery that had begun this journey had turned into a sort of shared anger on behalf of the audience and performer. Anger became more profitable than joy. Ironically, anger brought joy. Once that line became blurred and, like professional wrestling, the audience felt it was part of the show, the American id, that mother lode of uncontrolled impulse was tapped and could not be capped again. And each step along the way on this path ensures there will never be any going back. There is no undoing an Idea. Its acceptance may wane and wax, but once introduced, it exists.

the freedom is only an illusion, but the consequences are real.

Richard Pryor saw the proliferation of this new, ominous national mood that was using his comedy sensibility and formula to further agendas that he didn’t support and renounced forever the use of the N-word onstage. But the degradation and depravity in the dialogue continued unabated, and schoolyard jokes about dead babies and people with mental deficiencies or severe handicaps gave way to new depths of violence, racism, and sexism played for laughs. Sometimes, because the point of view was so fresh and unique, it could be argued that is was relevant and pertinent, especially if it was funny by the standards of the audience of that time. But more often than not, the humor and new latitude was parlayed for easy and cheap laughs. These simplistic laughs using shock value to blindly upend some superficial idea of the status quo without concern for consequences wound up creating a world in which freedom is absolute but consequences are nil. In fact, as it turns out, the freedom is only an illusion, but the consequences are real.

So that brings me to Louis C.K. and the comedy problem. I read that Louis C.K. had some bit about the Parkland survivors, which naturally got people in an uproar but reminded me of Lenny Bruce’s routine about Bobby Franks, the child murdered by the infamous Leopold and Loeb. Bruce’s routine involved the idea that Franks deserved to be killed because he was a “snotty kid.” Who would laugh at this? A nightclub audience coming to see a politically incorrect show late at night where forbidden ideas and words, from Black comics, female comics, fringe white comics, could be uttered. Not all that different, on the surface, from this recent set by Louis C.K. And audiences are still hungry to be challenged and provoked by stand-up material the way they are by a radical, transgressive movie or painting or poem or novel or play that they expect and want to be controversial. But up until recently, there was no social or digital media as a devouring force that must be fed material relentlessly. So when Louis C.K. does a set at an obscure club on Long Island, it is now impossible to keep it small and intimate and private. Just ask Michael Richards. But Louis C.K. knows this, too. He has been a massive success not just as a comedian, but as a marketer. He is a master manipulator of media and mediums. So we must acknowledge that even an experimental set in an obscure, out-of-the-way club is a major statement.

In a sense, he is telling America, “Fuck you. If you think that was bad, wait till my next set.”

With this new material, he is saying what most people would find abhorrent. But he is also saying something some people agree with. And, thirdly, he is saying something that some people find very funny. Remember, this questionable material was met with guffaws. I wonder how Louis feels about his audience—the one that has shunned him and the one that accepts him.

Can you admire Ginsberg? He was a member of NAMBLA. Can you admire Burroughs? He murdered his wife. Bukowski? Poor track record on beating and abusing women. Would we be able to ignore, even celebrate, their extremism today? It seems unlikely. For now, they are still in the canon—perhaps all to be rightfully reexamined at a later date. But who makes these decisions? Who sits in judgment? Is it society? Is it the market? Is it those manipulating the markets? Censorship, by the church or the kings or the corporations or the government or the prudes and hypocrites and self-righteous religious zealots in American society, is always intended to prevent you from learning something you have a right to know.

The country is not divided. It is broken. Into many pieces. And so is comedy.

I believe in absolute free speech. But I believe in the responsibility and consequences that go along with it. Sometimes it’s freedom and acceptance. Sometimes it suppression or ostracism. Sometimes it’s love. Sometimes hate. Sometimes it’s healing, and sometimes it’s suffering. Sometimes it’s violence. Regardless, in a supposedly free society, we can’t presume to tell writers, poets, novelists, essayists, playwrights, or comedians or just people “shooting the shit” on the street what to write or what to say and especially what to think. Most of our great art would be censored or have never existed under those conditions. If it were Turkey or Saudi Arabia, we might all be in jail. And who knows how far we are from that? But until then, remember, as it is, you don’t read all the books, see all the plays, or watch every movie or TV show or listen to all the music. And you don’t see every comedian, either. And there are many, laboring in obscurity, who are mining the same volatile field as Louis C.K—a comedy fueled by resentment and fear that the paradigm is shifting, and it’s leaving you behind.

The country is not divided. It is broken. Into many pieces. And so is comedy. Why wouldn’t it be? Gender, ethnicity, political affiliation—at first, the distinctions are stark. It’s hard to imagine these jagged fragments ever coming together. The very definition of what is funny, what is comedy, is being questioned. But that is good. And essential. A multitude of voices can be a healthy thing and lead to a new synthesis that creates the next paradigm in comedy. And maybe even in society.