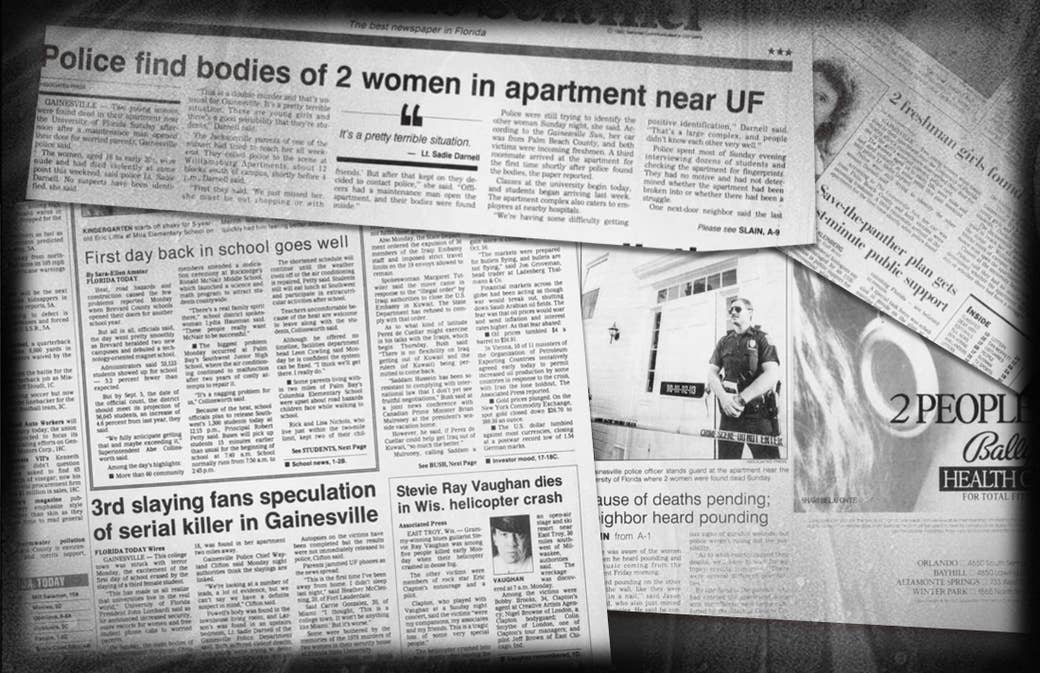

Everything that happened in Gainesville, Fla. happened very fast. The murders spanned just a few nights in August 1990. First, on the 25th, a Friday night, it was Sonja Larson and Christine Powell. On Saturday, it was Christa Hoyt. On Monday, the 27th, it was another pair of roommates, Tracy Paules and Manny Toboada. All of them were killed in their apartments. Hoyt's body was found propped up on a bed, bent over at the waist. Her nipples had been sliced off, and her severed head perched on a shelf on the other side of the bedroom. Some of the others were also mutilated. Every time, the weapon was a knife. Never a gun.

“We slept with steak knives last night,” one frightened junior at the University of Florida told the Associated Press at the time. Young people had just come back to town for the fall semester; four of the victims were students at the university. They were all living off campus, in the sort of ramshackle apartment buildings in dodgy neighborhoods that broke students often live in. There were no cell phones, no surveillance cameras back then. It was not so long before Ted Bundy, himself an accomplished killer of university students, had died in Florida’s electric chair.

Stories about the Gainesville mutilations were rampant. The bodies had been posed to strike horror in whoever came upon them. And the press kept repeating one rumor in particular, about a decapitation. You could not blame people for being afraid to walk the streets at night.

But the killings stopped after Paules and Toboada. Something changed. The police, for quite a while, didn’t know exactly what happened.

We've all seen Scream, which turns 20 years old today, but few know the true story that inspired it. The brutal murders of several young people that struck fear in a Florida community and sent ripples throughout the country. Most think fondly of the way Scream was able to humorously subvert the tropes of the horror genre in a stroke of postmodern, meta genius, but the fact remains that the story centers around a string of slayings. Teenagers "gutted like fish," as one of Scream's characters puts it. And in Gainesville in 1990, there wasn't any clever humor to take the edge off of what was going on.

For better or worse, however, the story is cinematic—and a young screenwriter named Kevin Williamson thought so too. Growing up in a tiny town on the coast of North Carolina, Williamson originally wanted to be an actor. But he got few roles, and couldn’t make any money, and as he told several journalists in the 1990s, he finally ended up housesitting in L.A. at someone's house in Westwood, a tony neighborhood near UCLA.

One night he happened to turn on the television, and there was a special on. It was about the Gainesville murders. It freaked him out so badly, he said, that he began to fantasize that a knife-wielding killer was waiting for him just outside the well-appointed house he was crashing in.

The experience is what gave birth to Scream, the screenplay Williamson promptly sold to the then-up-and-coming Weinstein Brothers for $400,000. The Scream movie went into wide release on December 20, 1996. It made over $80 million in its box office debut. As of now, it has grossed about $175 million, without counting the proceeds from the sequels. (If you did include them, you end up somewhere in the neighborhood of $600 million.)

As in Scream, the killer in Gainesville was what some who study serial crime would call a “marauder.” He appeared to be operating only in a small geographical area. The obvious assumption would be that such a criminal calls the area home. Some marauders are just lazy: they don’t want to have to travel far to commit their crimes. Others enjoy the terror they create. But there are risks to operating so close to your home: for one thing, people might recognize a criminal who flees the scene of the crime. Your chances of getting caught are that much higher.

Perhaps this explains why, within mere days of the murders, the police in Gainesville were already happy to tell the press they had a suspect. The man was a student himself, just 18 years old. His name was Edward Lee Humphrey, and on the Thursday following the discovery of the last set of murders, he had been arrested for beating up his grandmother. He had lived, for a time, in the apartment complex where Paules and Toboada resided and were murdered. A neighbor told the Associated Press that Humphrey had, from her vantage, had a “major crush” on Paules. “He’d fall all over himself to be near her or to help her. He’d go and sit by the pool and watch when she’d come out.”

Humphrey was obviously a promising prospect. There was the now-documented tendency towards violence, in the arrest for beating the grandmother. There was the personal connection to the victims. And there was the intriguing fact that, when Humphrey was taken into police custody, the murders had plainly stopped. The police department’s spokeswoman was hedging her bets, of course. “To me, it's frightening that there are so many candidates out there who could be considered candidates for a crime of this caliber," she said.

But she also called Humphrey a “very good suspect.” And the system appeared to agree. Humphrey was being held in lieu of bail, far longer than most assault suspects ever would have been. The police had heard by then that Humphrey was fond of wooded areas, so they had begun to search them. The police spokeswoman said they were doing it to try to eliminate Humphrey as a suspect, but it sure did not look that way to anyone watching the case. A writer named Ronald Smothers, a good crime reporter name if ever there was one, went down to Florida to check the whole thing out for the New York Times. He found the local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union up in arms, and the letters pages filled with people complaining that “mental illness is being put on trial.”

everything that happened in gainesville happened very fast...every time, the weapon was a knife. never a gun.

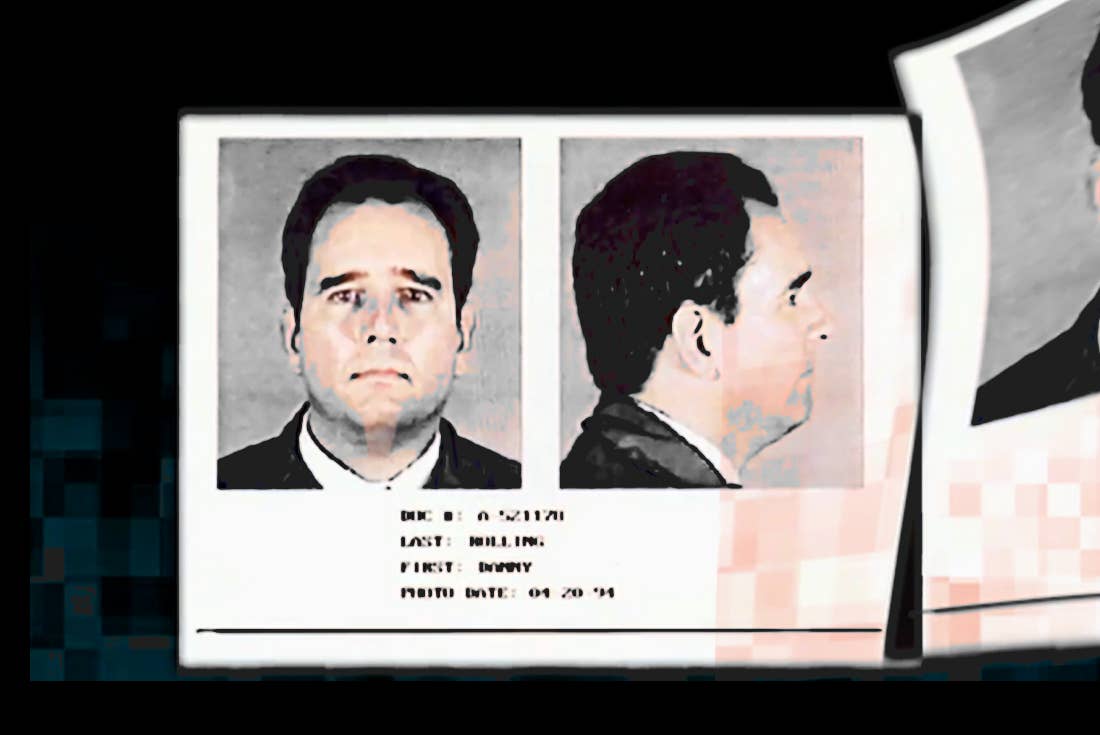

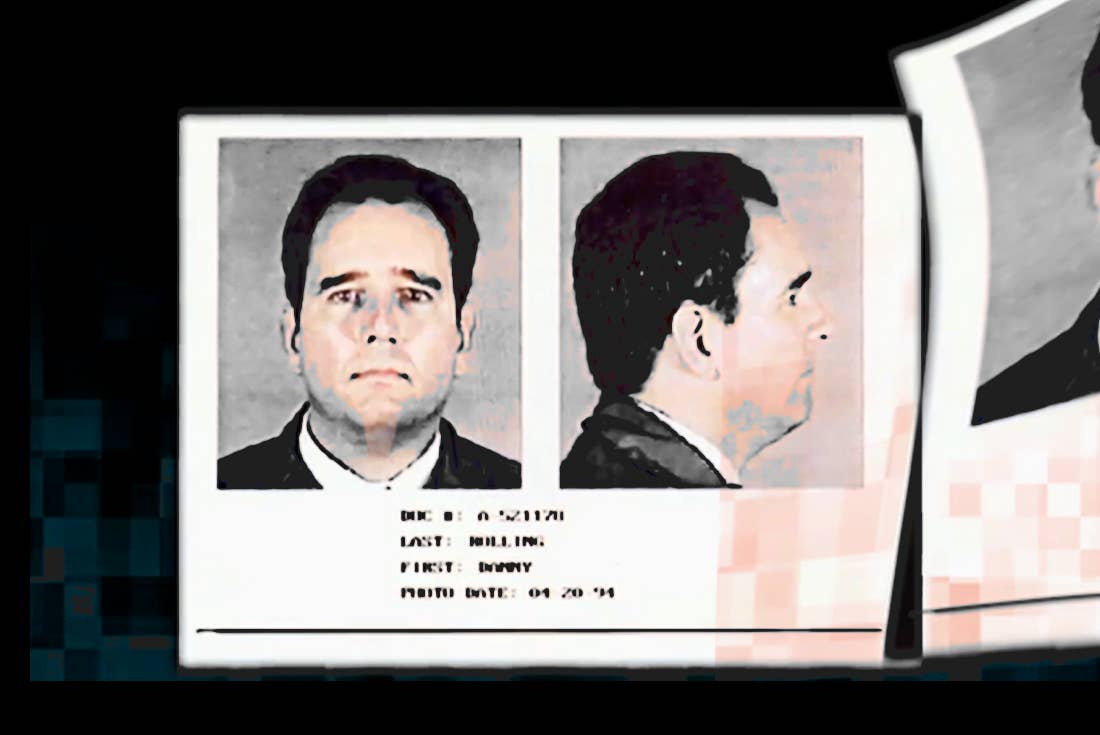

People often say that truth is stranger than fiction, but in the Gainesville case there was one cliched storytelling rule that reality obeyed. As anyone who watches a lot of scary movies probably already knows, the first, most obvious suspect usually isn't the killer. Humphrey would stay in custody; eventually he’d find himself in a state mental institution, thought too unstable for trial. But by January 1991, police came to understand that an entirely different person—36-year-old Danny Rolling, a man in custody in nearby Ocala—was more likely the killer.

Rolling was not from Gainesville; he was originally from Shreveport, La. He had come from what looked like a very ordinary home: dad, mom, brother. Rolling was the family screw-up. He was constantly being arrested, usually for theft. In May of 1990, he’d gone on the run from Louisiana authorities after shooting his father twice in the head. The father survived, but barely, losing an eye and an ear.

Rolling was the sort of person who liked to pile crimes atop each other; at the time of that shooting, he was already on parole for marijuana possession. He’d eluded authorities by stealing $21 from a local couple and telling them he was going to “Dallas,” then leaving his Louisiana car in the parking lot of a Motel 6. When the police found the car, they staked the place out for three hours, but Rolling was already long gone.

He had resurfaced on Sept. 7, when he was arrested for armed robbery in Ocala. His tactics had been very simple: Rolling walked up to a Winn-Dixie manager, held a gun to his head, and emptied the cash registers. He had not bothered to disguise himself, and witnesses identified him afterward. He was held on the armed robbery charges for months, in lieu of a $25,000 bail. (It turned out later that this was the third time, in his life, Rolling had been arrested for robbing a Winn-Dixie. He robbed a Kroger only once.)

When news reports first began to link Rolling to the Gainesville murders, even his father didn’t believe it. “He may be disturbed, but he ain’t guilty of that,” he told the Shreveport Times. James Rolling was a retired police lieutenant; he had a reputation to protect. He was also, according to his own wife, a man who had been very hard on his wayward and frequently felonious son.

But authorities had more than their suspicions to support them. For one thing, Rolling was actually a suspect in another murder back in Shreveport. In November 1989, Julie Grissom, her father Tom, and her son Sean had all been stabbed to death in a manner very similar to the Gainesville deaths. The killer had posed their bodies, too, in similar ways to the Gainesville victims. Rolling was, in other words, an even more perfect suspect. And he’d been right there, the whole time, while the police focused on Humphrey.

In Ocala, he crashed a car as he tried to flee authorities. That was how they got him, just a week or so after the murders. In fact, just a day after the last killing, the police had chased Rolling to his campsite in the woods, where they found bloodied clothing. They also found dollar bills stained with theft-resistant dye. And they found a tape with Rolling’s voice on it. It was a long and rambling monologue, taped over several days in the last month before the murders. On it, he sang songs, and talked to his family:

Well, Dad, I hope you're doing better. You know...probably don't even wanna hear from me. Well, you know, pop, I don't think you was ever really concerned about the way I felt anyway. Nope, I really don't. You never would take time to listen to me, never cared about what I thought or felt.

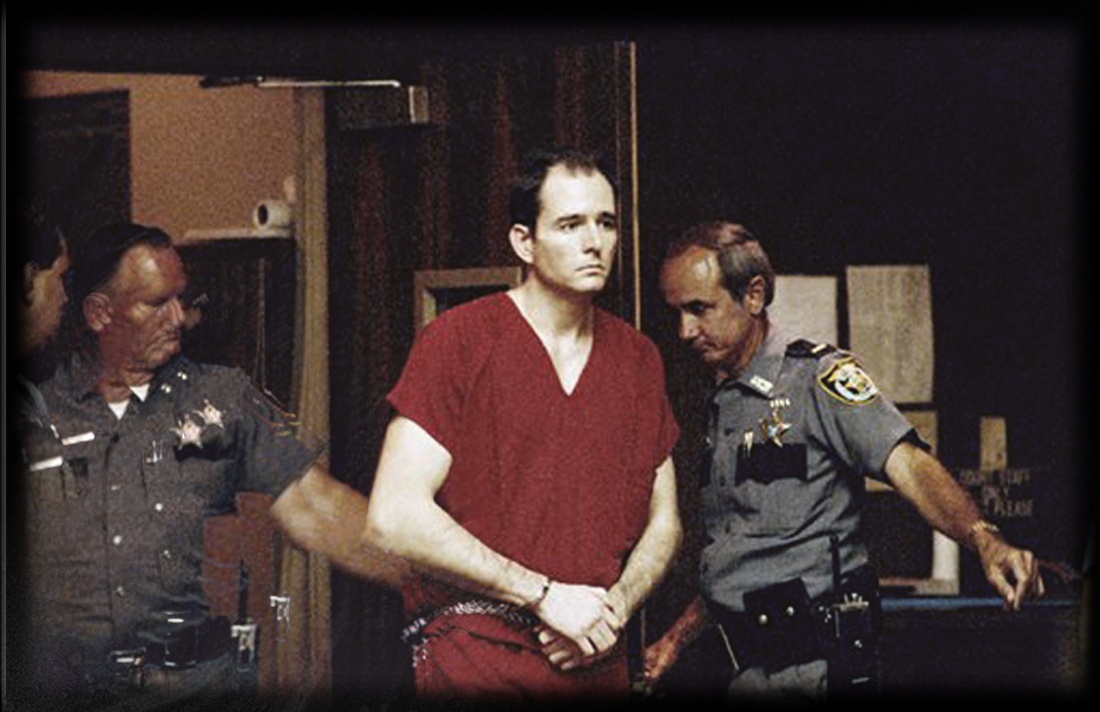

These were clearly the ramblings of a man unstable enough to commit the murderers. It took a while to put it all together, but by January it was obvious that Rolling was the killer. Rolling was tried first on the robbery charges in 1991, and given three consecutive life sentences for those. That trial gave authorities enough time to strengthen their case against him on the murders, for which he was tried in 1994. They played the tapes at the trial. Rolling, apparently, kept his head bent down as he listened.

“We don’t really believe in motives, Sid,” Skeet Ulrich’s Billy tells Neve Campbell in the climactic scene of Scream. “I mean did Norman Bates have a motive? Did we ever find out why Hannibal Lecter like to eat people? Don’t think so! See, it's a lot more scarier when there's no motive, Sid.” Billy and Stu do have motives though, much to their own annoyance: they’re thrill-seekers, sadists looking to recreate the scenarios of their favorite scary movies (along with some mommy issues for Billy).

In real life, Rolling’s motive was a lot more opaque. There was a trial for the Winn-Dixie robbery, one which got Rolling sentenced to life in prison. There was a trial for three other robberies he’d committed in Tampa, which piled another 170 years onto that first sentence. But there was no trial for the Gainesville murders, because Rolling simply pled guilty on the first day of the hearings. “Your Honor, I have been running from first one thing and then another all my life – whether from problems at home or with the law and myself,” the Orlando Sentinel reported him saying. “But there are some things you just can't run from.” No one needed to prove a motive here.

By then, Rolling had already established himself as a self-consciously theatrical fellow. He had a habit of singing in the courtroom, usually love songs addressed to his fiancée, Sondra London, a kind of serial killer groupie who would later be the subject of a short Errol Morris documentary. He seemed to enjoy the attention that his crimes had brought him. There were hearings, in the end, to determine whether or not he deserved the death penalty for the murders. Experts for the prosecution testified that Rolling had an antisocial personality disorder. They said that he knew what he did was wrong, in spite of any mental illness he might have. The jury believed them, and ultimately sentenced Rolling to death.

When it came time to explain his actions to the judge in the case, Rolling retreated into rhetoric:

There is so much I'd like to say, Your Honor, about our world and my beliefs and the destiny of man. However, I feel whatever I might have to say at this moment is overshadowed by the suffering I've caused. I regret with all my heart what my hand has done. I have taken what I cannot return. If only I could bend back the hands on that ageless clock and change the past. Ah, but alas, I am not the keeper of time, only a small part of history and the legacy of mankind's fall from grace. I'm sorry, Your Honor.

It appears that in being so coy, Rolling was simply biding his time—and protecting future income. He and his fiancée, Sondra London, had plans. The Florida state attorney’s office repeatedly sued to recover the proceeds from a book the two wrote together, and on a series of articles in a tabloid in which Rolling gave his account of the murders. They sued to stop him from selling his autographs.

All of these attempts to make money off the crimes still didn’t provide anything you could call an explanation for what happened. In the long, rambling thing (it’s difficult to call it a real book) that resulted from his collaboration with London, the culprit is mainly Rolling’s troubled upbringing. “As a child, my self-esteem was broken down,” Rolling writes. “As a result, there was an opening in my mind—a crack, if you will.” Out of that crack, Danny wrote, had come a “demonic entity who thirsted for blood.” He called this entity Gemini, and said that it was the reason he killed all those people.

Rolling would eventually be executed in 2006, though not before he sang again for the benefit of everyone present to watch him die. The song does not ever appear to have been identified, though CBS News reported that it was, “a hymn with the refrain ‘none greater than thee, O Lord, none greater than thee.’”

There is one last parallel to Scream, in all that. It wasn’t quite a motive, but we know this: Danny Rolling actually liked scary movies too. Apparently he saw Exorcist III at some point just before he embarked on his Gainesville spree. And in Exorcist III, which was a critical and commercial failure just like all the movies the Scream characters complain about, there is a demon called the Gemini. Rolling, just like the Scream killers, borrowed his explanation from Hollywood.