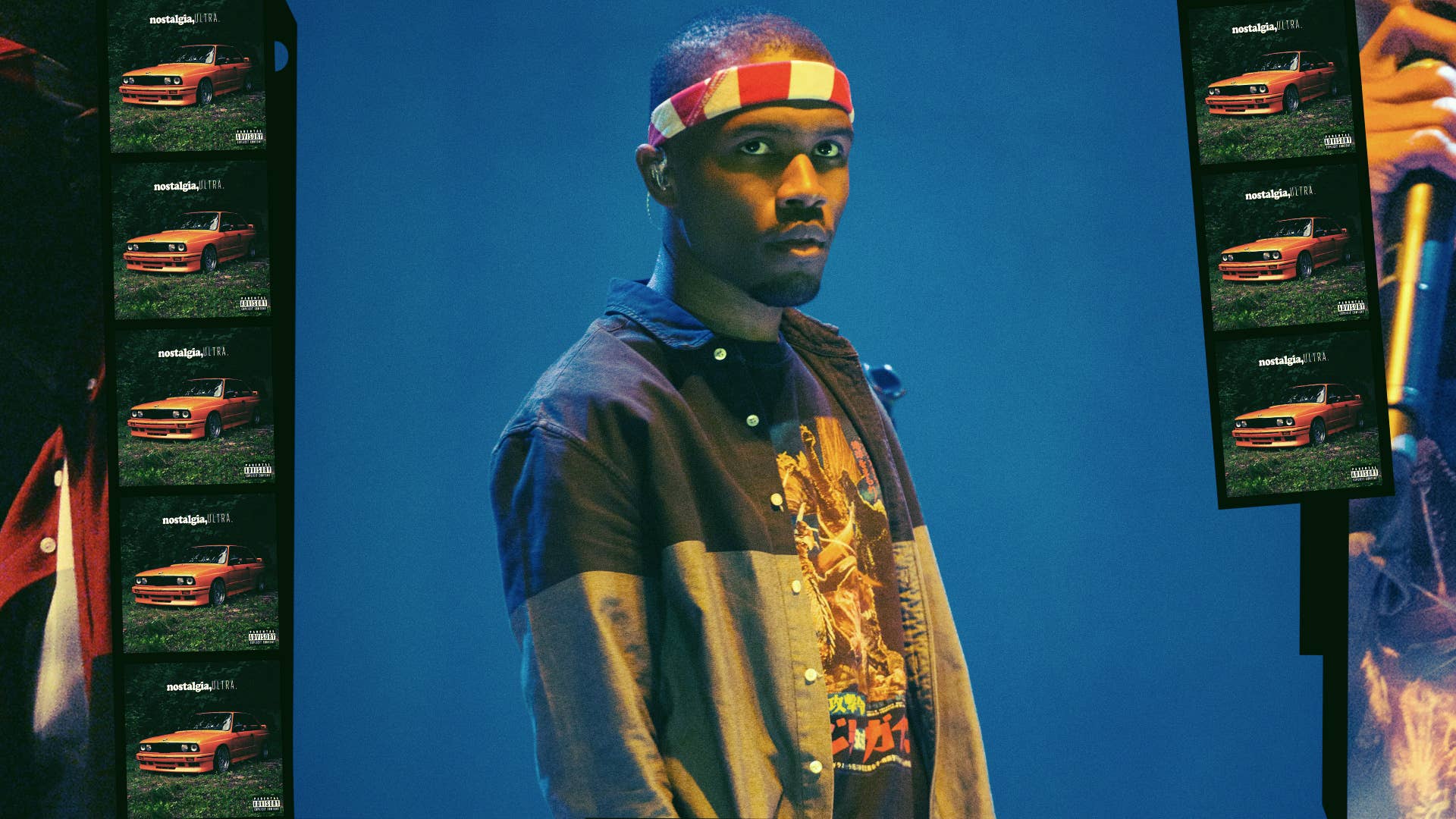

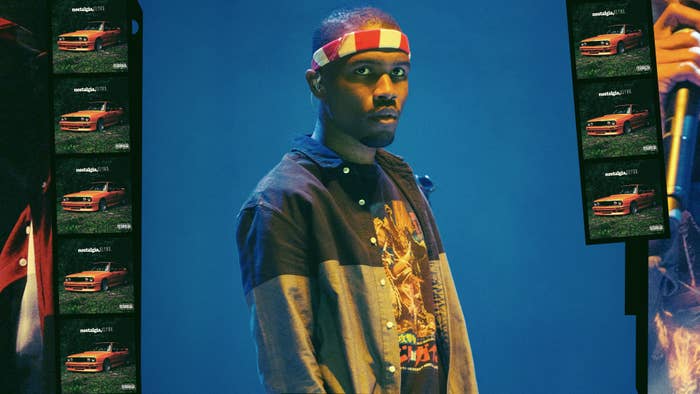

In the months leading up to Feb. 2011, Frank Ocean was a busy man. Searching for the perfect sound, he toyed around with different microphones and bounced around rooms in the home studio of production duo MIDI Mafia to make sure the energy was just right. He spread out photos of an orange BMW E30 M3 on a table in front of producer TROY NōKA to ensure his dream car would be dreamy enough for the cover of his debut project. He even watched Brandy cry over a “beautiful” song he had just recorded, only for him to re-cut it for the next six hours with his engineer.

By Feb. 16, Frank Ocean had almost everything where it needed to be. He was still missing two key ingredients for his introductory mixtape as a solo artist, though: the samples didn’t clear and, an even more difficult problem to shake, his label didn’t care. Neither of those things ultimately mattered, though. On that date, Frank still released Nostalgia, ULTRA. without clearances and without his label’s support, on a Tumblr page, under a completely different artist name, for absolutely free.

For his collaborators, it was a moment they’ll never forget. MIDI Mafia were relieved when Frank told them the project they helped fight for would finally see the light of day. Reggie “Red Vision”’ Rojo Jr. laughs now as he recalls the moment he spotted Frank’s Tumblr post, which contained a shoutout to the young engineer—who the singer affectionately referred to as the “raddest Mexican”—for working on what would be both of their first projects. TROY NōKA remembers it as the day he felt the stars aligning for Frank, who he had befriended years before, when the singer fled to Los Angeles from New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.

For the artist now known as Maejor, it took a plane ride and several nudges from friends to finally give Nostalgia, ULTRA. a try, before realizing that Frank Ocean was the same songwriter who he worked with on a track months before (which ended up on the mixtape). But the man he had known as Lonny Breaux—the detail-driven visionary who wrote songs for the likes of Justin Bieber and Brandy in the late ’00s—wasn’t Breaux any more. That winter day in 2011 marked the moment the world finally saw him as who he had become: Frank Ocean.

Ten years later, these memories serve as a reminder of the impact of Nostalgia, ULTRA. The surprise release was a paradigm shift, collaborators say, and one that set the stage for one of modern music’s most important figures. It boosted the credibility of Frank’s ride-or-die hip-hop collective Odd Future as a collection of creatives who were capable of, at that point, quite literally anything. And it helped set him up for a career of critically-acclaimed treasures, like his 2012 debut studio album Channel Orange, 2016’s label-exiting visual release Endless, and its immediate follow-up, Blonde.

On the 10-year anniversary of Frank Ocean’s breakout mixtape, we caught up with six collaborators, who shared stories about the making of the project. And frankly, we can’t help but feel nostalgic. This is an oral history of Nostalgia, ULTRA.

The beginnings of a solo artist

Stories from the studio

In the booth, whether it was at MIDI Mafia’s studio house in North Hollywood or TROY NoKA’s studio in Santa Monica, Frank Ocean’s collaborators began to question how few others at the time had noticed his genius. His imaginative storytelling, oftentimes drawing from different moments throughout history, left them stunned. And the effort he put into even the most minor aspects of the project made him, in their eyes, a “super perfectionist”; an artist who genuinely cared about the work he was creating. Even as his label made the studio sessions increasingly difficult financially, some of his collaborators fought to open his budget up and protect the recording environment for the sake of Ocean, and ultimately, the project.

Dirty Swift: It’s hard to say, but the majority of the tape was probably recorded at our house. We had like two or three recording studios in the house. It was like a community center.

TROY NōKA: I had a studio in Santa Monica. He would come by there all the time. Tyler, the Creator and Odd Future would be sitting on the floor. They were like kids, teenagers. They would be running in the hallway like, “Yo, I seen a ghost.” Like, bro, calm down. He would just come by the studio. It’s all love.

Bruce Waynne: Those different phases he was going through, it was like research. There was one point he set up one of the rooms in the house totally for his own vibe. He was there for maybe two or three days and he was like, “This isn’t the vibe.” He just kept going back and forth and he got into this groove. And when he got into that groove, it was over. It just started happening.

Dirty Swift: I remember him trying out different mics, and creating his own mics. He was just searching for sounds. I think Nostalgia was just a real experimental creation, and it came together over time.

Bruce Waynne: I remember when I walked into the session and I heard “Swim Good.” I was like, “What are we talking about?” He started laughing at me, and he was like, “Just sit back and relax.” I left, came back, and was like, “Yo, this shit is insane. But what are you talking about?” And then he told me. He got into this philosophical thing.

Dirty Swift: We did “Swim Good” in probably 10 minutes. I don’t remember when he wrote it. It was probably one of those 5 a.m. sessions and we woke up the next day like, “This is crazy.” At some point he’s like, “This is going on the tape.”

Bruce Waynne: I remember Swift walked in a little bit afterward and just started breaking the whole song down. I was like, “How do you fucking know what he’s talking about?”

Dirty Swift: He’s like 20 or 21 at the time and he’s talking about Vietnam and all these crazy topics. He would read and fact-check stuff. He’d be on his computer, on Google, just getting all these ideas. He’d go down these rabbit holes, and it was such a hard time pitching those songs for other artists, because he would have these things in there and they wouldn’t even be able to grasp how deep it was. It was really hard for him to write for other people.

He’s my favorite songwriter. I loved to wake up in the morning and be like, “Play me what you did last night.” I’d be like “Holy crap, this is amazing.” “Swim Good” was just another one of those.

Tricky Stewart: I thought he was a genius. His stories were Stevie Wonder-esque; they were Prince-esque; they were Michael-esque. It was some of the best storytelling, and the perspective, and the history of music that I had the utmost respect for. Even as a young person, I felt that Frank would be sitting next to the greats, when it was all said and done. [via The Fader, 2016]

Alex Al: I was definitely excited to work on music that was different artistically, and this particular song was original. From the very first time I heard the basic track of “Novacane,” I thought it was really unique in its sound. Nothing like that was on the radio at that time.

“He’s like 20 or 21 at the time and he’s talking about Vietnam and all these crazy topics. He would read and fact-check stuff. He’d be on his computer, on Google, just getting all these ideas.” – Dirty Swift

Dirty Swift: We were fighting with Def Jam a bit to get his budget opened up. We had to pay our engineers and stuff. There’s a lot of recording getting done for this artist to sign to Def Jam. It was a struggle to get the bills paid, so we were stressing about that, too.

Bruce Wayne: It was like, “This is my friend and he’s trying to figure out this tape.” So he’ll do a song with someone else and then play it for us and be like, “What do you think?” We’d give him our feedback and he’d either listen or he didn’t listen. We just gave him that room and that space to create. So when he was like “‘Swim Good’ is going on the tape,” we were like, “Whatever you want to do. The studio is yours, the engineer is yours, the room is yours.”

Dirty Swift: When Def Jam got involved, the engineers were like, “Am I getting paid for this?” We had to do that fighting. That messes up creativity a lot. Our frustration was just trying to keep the train moving and keep that supportive environment that he had the whole time. But once there’s money in the cloud, everybody starts wondering what’s going on.

Bruce Waynne: We were trying to protect the environment that we created. It put us in a different mode.

Tricky Stewart: Frank came in with the best intentions of being a great artist to a label. He was looking at it with an open mind. But bringing him into Def Jam was a little bit of a disaster. It was probably, in hindsight, a huge mistake on my part. The label wasn’t motivated by the signing. They didn’t give him the respect that I thought he deserved. I couldn’t really get Def Jam to respond to him the way that I wanted them to respond to him. [via The Fader, 2016]

Red Vision: He is actually a super perfectionist. Super, super duper perfectionist. My first impression of working on the album was like, “OK, well, holy shit. This is gonna be a really, really, really good learning experience for me because this guy is the real deal.” It was the best environment to soak up game and knowledge and really learn the ropes. It was like, “This is worth spending a lot of my time on, and going through some of the headaches. This is just unbelievable music we’re going to create.”

Alex Al: [The “Novacane” session] was highly creative, but really chill. I donʼt think Frank had recorded his vocals yet, but we knew his vibe and mood when we recorded the bass. I was intentionally sparse and supportive with the bass lines, but also melodic. The arrangement was there and you could tell the track was incredibly special. Tricky told me basically to just be myself on the track, and what you hear is what we came up with. I have a ’70s Fender jazz bass that Iʼve used extensively in the past with Michael Jackson, Sting, to Herbie Hancock, which Tricky just really loved, and he told me to always bring this particular bass to all of his studio sessions, especially this one for Frank. Tricky was always very serious about this bass, calling it the “Hitmaker Bass.” So thatʼs the bass we used to build a unique tone and sound to record the bass line for “Novacane.” Trickyʼs engineer, Brian Bluv Thomas, was also a master at recording the bass to sound big and full on “Novacane,” yet never overpowering the song.

Later, hearing the combination of Frankʼs lyrical poetry and Trickyʼs production, I thought this was an extremely original sounding record. Frank is an original artist and Trickyʼs production was amazing, too. Some real left-of-center, new Black music by a talented artist that was still accessible for radio.

TROY NōKA: He came through my studio in Santa Monica. I was playing him beats we had done. He was like, “Play me something that you’re not crazy about.” I played him this beat that I had just made the day before, one of those half-asleep-make-a-beat type songs. It was so simple: it was just piano and bass and four drum sounds. He was like, “Yeah, this is the one.” I’m like, “This one?” He goes in the booth and starts doing the melody. And then he’s singing “Lovecrimes” and I’m like, “What are you talking about?” By the time he got done with the shit, it was fire.

Maejor: Lonny came through the studio, and we recorded what later became “Dust.” The song was completely different, but it was the same kind of lyrics and the same structure. I thought he was super talented. And I only ever knew him as Lonny. I remember even when we were recording, he was very, very particular about his sound. He was taking it serious, which was dope for me to watch.

TROY NōKA: [For “Dust”], Frank came to me in a way of like, “I got this song” and I think he just sang it for me. I made a beat to it right there on the spot. I was working on a lot of pop stuff at the time, so I was putting little pop elements in there, like the little build. I made something from scratch and he went into the booth and sang it. That was that song. He told me that Bei Maejor had done another track to it, so I understood why he had a production credit on it when it came out, without touching the beat.

“It was such a hard time pitching those songs for other artists, because he would have these things in there and they wouldn’t even be able to grasp how deep it was. It was really hard for him to write for other people.” – Dirty Swift

Maejor: Months went by and he called me or messaged me like, “I’m working on the mixtape. Can I use that song that we did that day?” And it was just sitting on my computer. I wasn’t shopping the song or anything. We weren’t necessarily doing anything with it, so I said, “Sure, man, no problem. Just go ahead and use it.”

So he asked for the files, and I gave him all of the files. I think that’s when he took it with some of the producers he was working with at the time. I think he had to mold it into more of the sound that fit the rest of the project. That’s what I assumed, because from that moment, I didn’t hear anything else, until almost another six months down the line—maybe a year.

TROY NōKA: I was actually working with Mr. Hudson at the time. He was at my studio. I wanted to play “There Will Be Tears” for him. They wanted to even get him on the record. But I thought incorporating other songs and other genres was fly, because that’s what made it feel more like a mixtape. And that’s something a rapper would do. He could’ve just freestyled on it without the structure of the song or the intelligence that he learned from the years of songwriting. You could hear the intelligence that he learned to put in the work as a songwriter.

Red Vision: When we did “Strawberry Swing,” we were just trying stuff out. Just figuring out what felt right and what sounded right. [I remember] a normal day, he was like, “Yo, Reg, I got Brandy coming in to listen to some music and possibly lay some vocals on one of the songs.” So I’m super excited. I’m still young. Frank’s playing her a few joints. He plays her one specifically and she’s in tears, crying, saying, “This is perfect. Don’t do nothing to this song. This is absolutely incredible.”

She actually ended up laying vocals on “Nature Feels.” I engineered that one, too, so she hopped on that one. One of the songs that she was absolutely bawling over and going crazy for, still has not been released to this day. Soon as she left, Lonny tells me, “Hey, Reg pull that song up. The one that she was going crazy over. I’m going to work on the first four bars of the hook again, I feel like I have to recut this.” I can’t really be like, “Brandy was just…” Anyways, Lonny hears something that she doesn’t. We work on the same four bars for the next six hours, trying to get it right.

TROY NōKA: He really believed it and took it so seriously. I’ve seen him and his creativity—artwork spread across this table, the car, and everything like that. He takes it seriously. When you take stuff seriously, you’re unstoppable, because nobody can stop you from making things happen but you. We all have the power to bring things into existence that we see. So I always always believed in him.

Frank Ocean: When I did the artwork after we mastered it, I was feeling the same thing. That’s my dream car. It’s been my dream car for a minute. That E30 M3. That’s been my shit. I was the kid who had a bunch of car posters and girls in bikinis, all over my wall in middle school.

It’s nostalgic. It’s a longing for the past. That’s what this record felt like. I named it five minutes before we finished mastering. Right before we had to write the labels on the CDs and get out of there. ULTRA, because it’s also modern, because of the sonics of it. It felt right. That’s how I am. I just go with it. The only big debate was whether I was going to use the slash or the comma, but the comma felt right, too. [via Complex, 2011]

The surprise drop

It’s Feb. 16, 2011 and Frank Ocean—who at this point had been a member of rule-breaking hip-hop collective Odd Future for about a year—was tired of waiting to release his project. So he dropped ‘Nostalgia, ULTRA.’ on his Tumblr page, for free, for the rest of the world to finally hear. For some, it was a relief after years of watching him find himself. And for many of his collaborators, it came as a complete surprise. The sudden release of Ocean’s debut project led to Def Jam wanting to re-release it as an EP. Both “Novacane” and “Swim Good” were later released as singles, but the EP version of the project was ultimately scrapped.

Dirty Swift: He just hit us up like, “Yo, it’s out.” I went to Tumblr and I was like, “Holy shit, he finally did it.”

Bruce Waynne: We were like proud dads.

Dirty Swift: Maybe older brothers is a better way to put it… We were longtime producers. We were still like, “You have to set up your first single, you have to do this, you have to do that.” He just goes and pulls a picture online of some car, changes his name, puts this tape up on Tumblr under bluegrass. He just did whatever he wanted to do. And it worked.

Frank Ocean: Yeah, I tagged the album as bluegrass. I move a lot off instinct. I enjoy little details like that. I don’t want to seem like I have a cause against genres, or maybe I do, but I didn’t think about it that much. Bluegrass is swag. Bluegrass is all the way swag. [via Complex, 2011]

Bruce Waynne: He was saying the quality of music he wanted to put out and do, you don’t just put it on a mixtape. You don’t just give it away like that. After a while of just going through the frustration with the label, I think he was just like, “Fuck it.” This was the way he could do it without any interruptions.

Frank Ocean: Nobody likes hype. Well, I don’t like hype. Yes, it was a conscious decision. A couple of my close friends actually thought U was out of my mind [for not promoting the mixtape]. Thought I was “throwing it away.” [via Mustafa Abubaker, 2011]

Dirty Swift: We were so used to him, we were a little numb to his genius. So I think it was cool to see everybody finally see what we saw the whole time. Like, we were pitching songs and brought him to different A&Rs as an artist, like, “What do you think?∏ And they’re like, “I don’t know.” Don’t people see what we see? Like, he didn’t fit in a box. But we were like, “I think this guy’s a genius.” You know, it was really hard to understand why nobody recognized that right away. And then, when the tape came out, everybody was like, “This is next level. This is genius.” Finally, people saw what we were seeing the whole time.

Tricky Stewart: When you’re really special, your first work is going to be special. I knew it was special. I was getting on airplanes passing out his CDs to strangers. I printed out the CDs myself and sent them to every family member I had. If I saw somebody that was cute, I was giving it to her. I just knew that what I was holding needed to be heard. Frank was bubbling over with creativity and Nostalgia, ULTRA. was the first thing that he got a chance to get out there unobstructed, without anybody’s influence other than his own.

He had his own thoughts up there. In that moment, we lost Frank Ocean—as a major record company, and from this industry as we knew it. When the label rebuked him and he found himself, the label lost it for everybody involved. [via The Fader, 2016]

“After a while of just going through the frustration with the label, I think he was just like, “F*ck it.” This was the way he could do it without any interruptions.” – Bruce Waynne

Alex Al: Later on, when I heard the entire project in its entirety I thought, “Wow, this is gonna break new ground musically.” It reminded me of the impact when we all first heard D’Angelo’s Voodoo record, yet in a totally different way. Frank was in his own lane creatively, and the bass, chord progressions, drum programming, and production of the songs gave him great support.

Red Vision: I was at home in California and when it dropped. It was out of the blue, and I saw that he shouted me out. That was love, too. He wrote, “Special thanks to Reggie Rojo, the raddest Mexican.” That was hella random. Bruce told me to check his Tumblr account because that’s where he released it. I went to go look and I was like, “Oh shit, the album’s out.” I never heard the name Frank Ocean come up at all. It sounds a little classic, nostalgic, and serious. It described the entire tape.

Frank Ocean: I changed my name on my birthday last year. It was the most empowering shit I did in 2010, for sure. I went on LegalZoom and changed my fucking name. It just felt cool. None of us are our names. If you don’t like your name, then change your name. I’m only a few steps into the process, so I probably shouldn’t even be talking about this, but by the beginning of summer, I’ll be straight. I’ll be boarding planes as Christopher Francis Ocean. [via Complex, 2011]

Bruce Waynne: We really didn’t know it was gonna happen, because literally, he just woke up one day, and told everybody his name was Frank Ocean. It was on Tumblr. There were multiple conversations about how he wanted to release it, how he wanted to drop photoshoots, and all this other kind of stuff. And I think, like we said, he just put that shit out… He knew he wanted to change his name and build an aesthetic. So it just became more of an ongoing conversation. Frank Ocean is Frank Sinatra and Ocean’s Eleven. That’s where it all kind of comes in. The whole vibe and mystique and all that kind of stuff.

Dirty Swift: He was always evolving. Back then, it was just, “What’s he coming in with today?” So it wouldn’t surprise me if he changed his name again now, if that’s what he wants to do. He’ll ask people he trusts what they think, and then he’ll go off and just do his own thing. He’s always doing that. Nothing surprises me anymore with him.

We didn’t see him plan it. He just took everything, went away, figured it out, and it was on Tumblr. The Odd Future connect helped build momentum really fast, but we’re like, “Holy crap. This thing’s going viral.” From the label side, I can understand their frustration. He wasn’t listening to anybody, and just did his own thing. They could have tried to be more supportive. Labels are very corporate, so it’s hard when you just want to go out and release stuff.

Red Vision: I knew that it was gonna be dope. I knew that the music was crazy, but I did not really expect for it to go that fast. It really happened so fast. It’s crazy. But it was amazing to witness. It solidified myself and my craft. Like, you’re doing the right thing as an engineer.

Bruce Waynne: There weren’t a lot of R&B artists doing mixtapes. That was rare. You know? Like, that just didn’t exist.

Maejor: A few different people asked me, “Hey, did you hear Frank Ocean’s music? You should listen to music.” So I’m like, alright, let me get on a plane and let me check this guy out. So I played the mixtape. And I’m like, “That sounds like Lonny.” I was just so confused. And then I heard the song that we did. I wasn’t that close with him, where I knew what his plans were. I just knew him as Lonny, and we made a cool song. So it is all kind of connected. And obviously, by that time I was hearing about it, I’m sure many other people were hearing about it, too.

TROY NōKA: John Legend posted it, and I was like, “This is about to go crazy.” You could feel the momentum with the mixture of Odd Future turning up, and you could see the stars aligning from the outside. From the inside, it’s family. From the outside, it was like, “The stars are really aligning for bro.”

Frank Ocean: Drake reached out to me when the record came out and paid me a compliment about the sound of it. I respect Drake not only as a creative person, but as a business mind as well. I think Drake’s important. The moral of the story is Drake’s ill, and I’m ill. When I talk about the girl listening to Drake and Trey Songz on “Songs For Women,” that was more in sarcasm, and in jest, than it was in seriousness. I don’t think any person in a serious relationship is threatened by the person on the radio. It’s just a cool detail. It’s not like you’re going to go off on your girl because she’s listening to whoever. That doesn’t make any sense. That’s some other shit. Like, you’ll fuck with your girl. You might poke fun at her like, “You know I be recording and shit, but you don’t listen to my shit like that.” It’s funny. The shit doesn’t make it to a serious point, ever. [via Complex, 2011]

Dirty Swift: I remember hearing the story that people at Def Jam were trying to find this Frank Ocean guy and sign him. And the irony was they already had, you know, and it just goes to show you the label mentality. They just signed stuff and put him on the shelf.

Tricky Stewart: At the end of the day, I think Def Jam created a monster that they couldn’t control. He just treated them how he was treated. There’s too many artists out here with that story. Luckily for Frank, he was able to turn a negative time and a negative period into something that worked for him and his family. [via The Fader, 2016]

Dirty Swift: When “Swim Good” came out [as a single in October 2011], Def Jam was wanting to release the mixtape, so we had to get all that business sorted out and that was a pain in the ass. And then Def Jam just made it difficult at the time, [because] all the samples couldn’t get cleared. So we’re like, “Is this a mixtape or not? Is it gonna be an album?” It was supposed to be an album, but they couldn’t clear everything. So we were all caught up in that while this was going on. We didn’t have the luxury to just sit down and watch [the process]. There’s a lot of mystery about how he put it all together. At the end of it, he just went off to a cave and picked all this stuff.

We saw him struggling with the label, too. We even set up a showcase. Tricky came and he wanted to see how he performed. He rehearsed and did all his music at this showcase in one of those little rehearsal studios in L.A.. We set it up like a real show. There were all these hoops he had to jump through just to try to get recognized by the label, and finally he was just like, “Screw it, I’m gonna do my own thing.”

“He just goes and pulls a picture online of some car, changes his name, puts this tape up on Tumblr under bluegrass. He just did whatever he wanted to do. And it worked.” – Dirty Swift

Maejor: It was super cool to see how that came about. It even surprised me because I didn’t even know that Frank Ocean was the guy I was working with. And I think that’s what’s cool about the cover, too. He didn’t show his face or anything. I think it was kind of like a magical experience.

Bruce Waynne: And then, after it started to connect, people started taking other records out of him and started leaking them [as The Lonny Breaux Collection]. It was like a nightmare, man.

Dirty Swift: So much music that we did, we did it for other people, too. It wasn’t even necessarily for him. And then it got tagged as his music with MIDI Mafia. It was like 30 songs out there. Nothing could be done with those songs anymore. That represents so much work.

Becoming nostalgic for ‘ULTRA’

Ten years later, the producers and instrumentalists who worked on ‘Nostalgia, ULTRA.’ consider it a turning point in music history. As they see it, Ocean built a movement; his own movement.

Red Vision: It’s a classic. As soon as it dropped, it made an impact. It just shifted R&B, or alternative R&B—you can’t really give it a genre. It’s so many different types of varieties and styles. It’s crazy.

Bruce Waynne: We look at it like we helped build the format of how music is actually done. How music is launched. You could be signed to a label, drop something, have real success, and still figure out how to get it into that system. There was no blueprint for that. Me, Swift, and Frank, I feel like that’s what we were doing.

Dirty Swift: It changed the game. The whole paradigm shift. After that was the Weeknd. After that was these new artists who came up in that alternative R&B lane. He was the first. And now it’s just, like, Beyoncé drops an album. There’s no promotion, she just puts it out like a surprise drop. That’s that’s the new way of doing it. But that’s because of Nostalgia, ULTRA. That was a pivot point.

Alex Al: Thereʼs only one “Novacane.” It’s special to have been a part of that on an artistic level. The song has definitely earned a place in hip-hop, R&B, and popular music history. Once in a while, when I hear both the regular version and the instrumental mix of “Novacane,” especially, it still sounds as other-worldly as when I first heard it, yet it has some earth to it organically.

TROY NōKA: It’s an undeniable classic. I look at the comments on some of the songs when I come across them, and I see people are still listening to it and enjoying it. That’s beautiful.

Red Vision: It was a big deal for mixtapes, and even just for songwriters. It influenced a lot of songwriters to just go ahead and pursue their artistry. It was definitely a moment. Man, I’m so glad that I’m tied to that legacy. I’m really grateful to be a part of the whole experience.

“It’s an undeniable classic.” – TROY NōKA

Maejor: It definitely feels like something that has become a part of popular culture, which is so because it was a mixtape and because of the story behind it, being signed to the label and they weren’t necessarily promoting him or whatever. And then he created this. That, for me as an artist, is so inspirational and cool to see that you can create your own path.

Dirty Swift: I have a lot of respect for him that he didn’t take the traditional path, you know, doing radio when they told him to do radio. He just put out music he really believed in and built his own movement. He went through a lot of iterations of what name he was going to use, what the mixtape was going to be called, and we watched that process. It was a game-changing event to be a part of that.

Tricky Stewart: The next time that there is a great talent in this business—I’m talking about those special talents—you can’t be so sure that he’s going to walk through your doors anymore. There’s other options out here. [via The Fader, 2016]

Bruce Waynne: It was like a physical maturity, watching Frank. We watched him start out with writing, being at the studio every day, just working records. We saw a lot of struggles in regards to things like, “Damn, man, I want to do this my way, but I’m writing these records for other people, so I got to write it this way.” And that tape was just more, like, “Fuck that.” He just drew a line in the sand, [showing] what he thought quality was and what his generation was thinking at the time. It kind of defined this generation. Look at all of these artists right now. They were all inspired by ULTRA.

Frank Ocean: One of the best pieces of advice I’ve ever heard was, “Continue doing what you’re doing.” I’m going to continue to be guided, and continue to progress. I’ll be getting on the road and working on new music. I’m nine or ten pieces into this next body of work. I’ll be writing with people that want to write with me, and that I want to write with. And that’s all. Just keeping it moving. Continuing to do what I want to do. [via Complex, 2011]