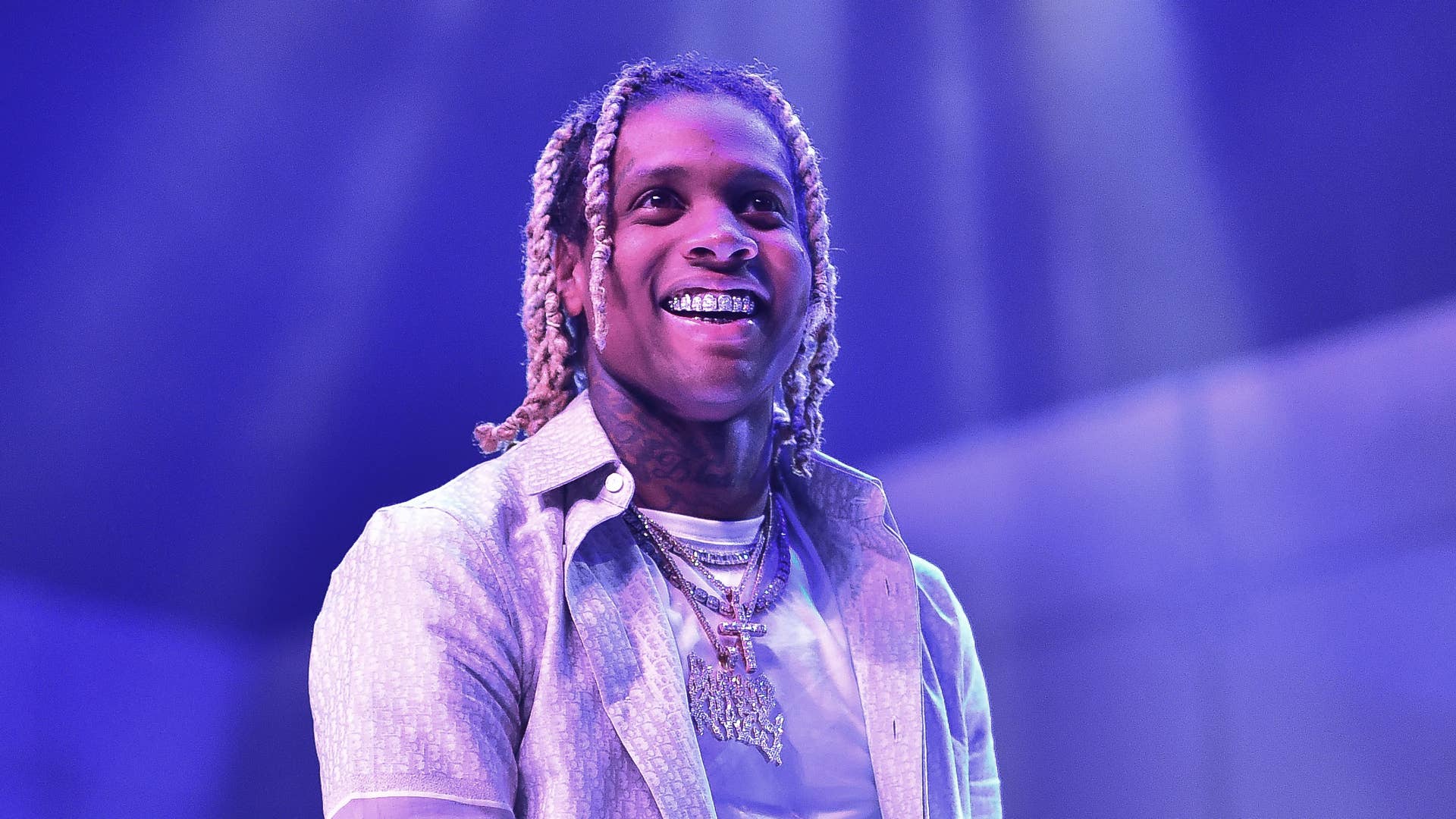

Last week, Drake released “Laugh Now Cry Later,” the first single from his next album, Certified Lover Boy. The melodic track features Lil Durk, a development that many didn’t see coming. Much of the discussion about the song centered around the notion that Drake gave Durk “a look,” continuing a trend of the Toronto artist helping entrench Migos and other then-emerging artists in the past.

But Durk isn’t a newcomer. He’s been in the game for nearly a decade. He was an important figure in Chicago’s early drill scene, and the syrupy brand of melodic trap he explored in the early 2010s helped influence the sound of a whole generation of new artists. Numbers be damned, he’s an influential figure in hip-hop. Drake wasn’t doing him a favor; he was paying homage.

The reaction to “Laugh Now Cry Later” is another example of rap fans being too conditioned to evaluate cultural relevance through a capitalistic lens. Yes, in the music industry, some artists are regarded as more commercially palatable than others, so they’re primed to get bigger budgets that often beget bigger sales and stream numbers. But that doesn’t mean that a higher selling artist is inherently superior or more relevant.

Cultural relevance should stem from how compelling and influential an artist’s work is, not how deep their marketing budget goes. The music industry is an inherently exploitative buzzsaw. It’s common knowledge that many executives are out of touch and use numbers as the lowest common denominator. They’re run by the same people who needed to be forced by George Floyd’s murder to acknowledge that the music they profit from reflects real social issues. It’s the same industry where colorism among Black women in rap is blatant.

It’s questionable how much label execs even appreciate Black artists beyond their profitability, so why should their metrics shape the paradigm of how we evaluate Black artists? If we know capitalism works against Black America, then why should a capitalistic entity be dictating cultural relevance of Black art?

Categorizing artists by their commercial stature is inherent erasure, which has affected the perception of artists like Freddie Gibbs, Phonte, and CyHi the Prince of late. Their plight underscores a fact that’s obvious to some, but overlooked by many: impact and relevance in rap has to go deeper than numbers. It’s time to evaluate how deeply we’ve let capitalism skew our perception of cultural value.

In 2011, Drake dedicated a BMI Songwriter’s Award to Kanye West, Outkast, and Phonte of Little Brother. He said all three men influenced his songwriting prowess in different manners. While two of those acts make sense to most fans, many may take pause at Phonte’s inclusion, though Drake’s early material resembles the work of Phonte’s Little Brother and Foreign Exchange more than Kanye or Three Stacks. Phonte replied to Drake’s nod by noting, “I’d much rather he had dedicated himself to finishing a verse for one of me and 9th’s songs.” He also bemoaned, “To my knowledge, [a collaboration] is not happening. We’ve made contact with each other but all of my attempts to make something real happen have led to a dead end.”

Impact and relevance in rap has to go deeper than numbers. It’s time to evaluate how deeply we’ve let capitalism skew our perception of cultural value.

Drake twice collaborated with Phonte on Comeback Season’s “Think Good Thoughts” and 2008’s “Don’t You Have A Man.” But once Drake vaulted into a new level of fame, it apparently became harder for it to happen. Drake later replied to Phonte in a Village Voice interview, admitting, “That was my fault. I talked to 9th Wonder about trying to make it happen. We’ll get it eventually. He knows he’s one of the biggest influences on my career.”

But unfortunately, nine years later, it’s never happened. It’s unclear why the collaboration has yet to materialize, but Drake has frequently collaborated with other influences like Jay-Z and Kanye—two artists who are always commercially viable. A Drake-Phonte collaboration would have been an opportunity for Drake to introduce Phonte to a new generation of fans, but instead, there are young people who feel like a listener of Little Brother’s 2019’s May The Lord Watch, who questioned, “Listening to this Little Brother album and this Phonte nigga sound like Drake. Wtf going on?”

What is going on? Phonte and Little Brother were once deemed “too smart” for BET, who didn’t play their “Lovin It” video. Apparently, their mature approach to rap hampered their commercial viability. They’re not regarded as unsung because of a lack of talent, but because of an industry that didn’t know how to market them, and hence refused to. To see that circumstance meander into major publications crowning a Phonte disciple as the inventor of singing and rapping seems downright cruel. In this circumstance, we’ve let numbers make a falsehood true, highlighting the inadequacy of commercial metrics as a barometer of cultural value.

The same thing is happening with Freddie Gibbs, an artist who has released seven well-regarded projects in the 2010s, including two bonafide classics in 2014’s Piñata and 2019’s Bandana with Madlib. Just last year, Gibbs released two albums that heavily populated album of the year lists in Bandana and Fetti, but he was regarded as “absolutely irrelevant” by DJ Akademiks earlier this year (after Gibbs himself called Jeezy “irrelevant”). Akademiks contended on Everyday Struggle that, “Relevancy means is your music actually doing anything? And to be honest, other than the few people who f*** with Freddie Gibbs, what relevancy does he have?” The ease in which Akademiks could link “doing anything” with selling a certain amount of first-week units exemplifies the genre’s dependence on metrics to tell the tale.

We have 50 Cent, in particular, to thank for the first-week sales argument. He was the first artist to place a heavy emphasis on first-week sales, visiting Hot 97 in his commercial heyday to read out other artists’ sales tallies. He also got involved in the famous first-week sales competition with Kanye West. But by 2015, the Queens rapper, who once ruled the radio, expressed a new understanding of success beyond the bounds of previous arbiters. He proclaimed, “You can’t really go by radio. You gotta put the music out, and let radio catch up.” And if they don’t, who cares?

The value of Black art needs to be reconsidered outside the scope of what corporations deem worth investing in.

G-Unit released The Beauty Of Independence in 2015, an EP that didn’t boast titanic sales or radio singles. But 50 noted it was a “fun” project that marked a chance for them to reach out to fans who love their gritty brand of rap. He told USA Today, “You can't stay in the cookie-cutter mentality, doing the same thing you used to do when things are dramatically changing around you. You've got a guy who says he's been in the music business for 20 years? Listen carefully to what they say after that because he probably has no f*ckin’ idea what's going on.”

No artist’s relevance should be framed by their adherence to oblivious record execs, and Gibbs is a prime example. He’s released a lot of his music independently, which will engender a more limited commercial scope than major acts. In the independent rap world, however, it’s not about metrics as much as fulfillment. The internet offers a chance for an artist to be self-reliant, building a relationship with fans who appreciate them for them, not a label’s ability to advertise them. Gibbs’ self-reliance allowed him to stick to his guns and become one of the most consistently high-caliber MCs of the 2010s, a dignification that supersedes any numbers.

Freddie Gibbs has actually said that the unprecedented attention he garnered from Bandana, released on RCA, weirded him out. He told Complex, “I stepped back because I got to a different kind of notoriety when I made Bandana. The rush of the people that was saying that they didn’t like my music at first, but now all [on] the bandwagon, that just gave me time to really be like, ‘Do I really even want to rap anymore?’ Rap, to me, is just so superficial.”

He had brushed against the cohort of fans who covet commercial relevance and didn’t enjoy how fickle they were. His statements reveal that sometimes, relevance is just a connection with fans clamoring to be in on a trending topic. That may allow an artist to strike while the iron is hot, but conditional engagement isn’t a sturdy basis for a lasting artist-fan dynamic.

It makes sense for artists to focus only on those who genuinely appreciate them. But even the basis for appreciation needs to be expanded. Last weekend, several CyHi the Prince Astroworld reference tracks leaked. It’s unclear specifically how much music CyHi ideated for Travis Scott, but the Atlanta artist has long been a crucial figure in G.O.O.D. Music brainstorming sessions, boasting over 30 writing credits on Kanye songs. Whether his contributions to Astroworld were a little, or a lot, the amount is believable. Despite his documented proximity to beloved artists though, it feels like CyHi doesn’t get his just due as an artist.

While discussing his contributions to Astroworld and Ye with Complex in 2018, CyHi said that across genres, “The biggest stars aren’t in there by themselves. It’s 30, 40 people—you got trumpet players, lyricists, writers.” The stars will go on to generate millions of units and sales, but contributing musicians are rarely mentioned, much less lauded, in the evaluation of the work. It’s an inherently capitalist dynamic. Whether it’s a Travis Scott studio session or an Amazon warehouse, almost every fortune subsists on the labor of people who go underappreciated in the process. We focus on the primary beneficiary, but ignore the workforce. In the arts, where so much of an artist’s career arc hinges on perception, that has to change.

Modern music fans aren’t accustomed to checking the credits for writers and other contributors, for many reasons. Once projects went digital, it was no longer a part of the process to dig through album booklets, which housed details of a project’s conception. And aside from high-profile releases, that’s still the case.

But even when songwriting contributions are reported on, they’re rarely factored into an artist’s impact on hip-hop. By sales-driven estimations, CyHi’s figures deem him commercially “irrelevant.” But how could that ever be the case when he’s contributed to some of the culture’s most impactful music?

CyHi also told Complex he was going to release a 7-track album with Kanye West, but it never happened. How could a G.O.O.D.-outsider, Nas, get one, but CyHi didn’t? The development could be attributable to a range of factors, but it certainly looks like CyHi’s contributions are being taken for granted. He was financially compensated for his Astroworld and Kanye contributions, but his cultural worth should be higher.

His circumstance is akin to that of Freddie Gibbs and Phonte’s, as artists unappreciated by an industry that gauges value by the numbers. That reality has manifested in different manners for these men, but they’re all attributable to the pitfalls of a capitalistic view of rap relevance.

The value of Black art needs to be reconsidered outside the scope of what corporations deem worth investing in. Too often, cultural appraisal is swayed by consumerism.