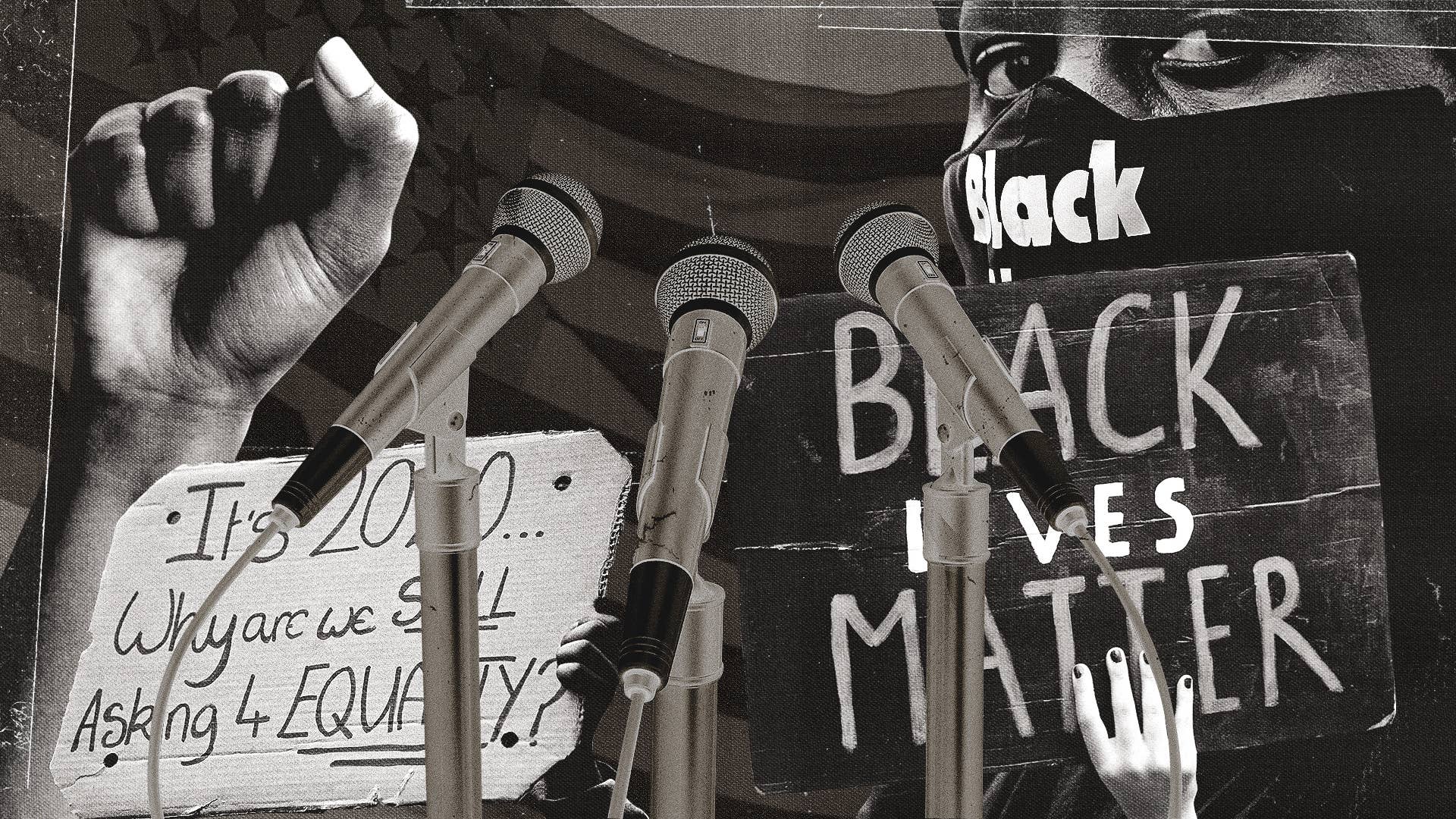

The music industry is primed for a reckoning.

Black Out Tuesday—the music industry’s first attempt to “stand in solidarity with the Black community” amid nationwide protests against police brutality and racism—was met with criticism from many, but it provoked a productive reaction. It inspired artists, listeners, and even some music executives to talk about what more could be done to support Black people.

“The music industry makes so much fuckin’ money off Black people, Black artists, Black listeners, Black supporters,” Kehlani tweeted on June 2. “These posts ain’t doing shit.”

“Wish these labels were as creative with ways to help black artists as they are with the 200 page 360 deal contracts they enslave their art and careers with,” Kenny Beats wrote.

Some major labels have started rolling out initiatives in response. Sony Music and Warner committed to $100 million donations to support “social justice and anti-racist initiatives.” Universal pledged $25 million. And last week, the Recording Academy announced it would be dropping the word “urban” from categories describing Black artists in hip-hop and R&B.

This is a good first step, but it’s just scratching the surface of the changes that need to take place in the music industry.

“I think donating money is great. I wouldn’t dismiss it,” artist Open Mike Eagle tells Complex. “I think if they’re helping organizations that do good work by giving them resources. That’s great. But I think the music industry might have it better. There’s a lot more that they can do as compared to other corporations.”

Complex spoke to several Black artists who offered some insight on what they would like to see change in the music industry.

Diversity in the boardrooms

Many artists point to the lack of diversity within boardrooms as a major problem. While there has been some progress in the last few years with more Black people being promoted and hired to executive roles, there is still a large discrepancy between Black people and white men in positions of power.

“They need to hire Black people,” Killer Mike tells Complex. “That's what the Black community would like to see. There's been a whole mid-level management of sorts. The biz is wiped out. Where are our Roc-A-Fellas? Where are our Ruff Ryders? Or LaFace? Where are Suave House, Luke Records, Rap-a-Lot? Some are still here, but in smaller margins. My thing is, let’s see some hires.”

Hiring a more diverse boardroom will likely improve and strengthen relationships with artists, Drakeo the Ruler says.

“They need to hire Black people. That’s what the Black community would like to see.” - Killer Mike

“I need a label to understand my situations and what I’ve been through—police targeting, all that shit,” Drakeo explains. The rapper is currently being held in custody as he awaits a new trial for a 2018 case. “I can’t sign to no label and they want me to do popstar shit when I’m a street nigga. That shit don’t work. You have to understand me. Not no person that's just going to tell you, ‘Don't do this. Don't do this.’ You need somebody who is like, ‘I understand, bro. I'm not going to tell you what to do, but I think it'd be best if this.’ Motherfuckers, they just be like, ‘Don't do this, and don't do this.’ Then they want to drop you when you get in trouble. Like bro, this is what got me here. I been getting in trouble.”

Echoing Drakeo’s sentiment, Guapdad 4000 says, “If there was some type of cultural connection, some type of bond there with our upbringing and our knowledge, it would enhance the experience better.”

Reflection and education

Following the black out, major labels like Sony, Warner, and Universal pledged to form departments that would directly address diversity. A spokesperson for Def Jam Records also confirmed the company hosted a town hall meeting for employees on June 1. But those open forums mean nothing if the individuals in the room aren’t having open and reflective conversations.

Open Mike Eagle says it’s important that those discussions look at how companies have played a role in silencing Black voices.

“If they’re concerned about cultural conditions, think about their products and their systems as it relates to or affects those cultural conditions,” he says. “I don’t think that takes a ton of education. That just takes them taking a good, long look at how they do things to see if there’s a possible effect that they’re not quantifying.”

So, what are those questions they should be asking?

Open Mike Eagle outlines a few:

Are there mental health ramifications to the way they do business?

Is it possible that how they have promoted and groomed [artists] might have destroyed their life in some sense?

Is there support for these artists when they do need help—mental health, substance abuse?

Are they checking in with how their artists are actually doing?

Are they checking whether or not the images they are portraying is actually who they are?

“I'm not sitting here saying any of that is definitely what happens,” Mike adds. “But what I would want them to do, if they're taking a moment of reflection, is to start asking questions.”

Amending contracts

Most artists agreed that the first action the music industry should take to support Black voices is to amend or renegotiate recording contracts so that they are more beneficial to Black artists. That means adjusting language to be more comprehensible, lifting impossible multi-album commitments, and fixing ownership rights.

“When you got somebody like a record label, so deeply embedded into Black culture and literally have been terrorizing a lot of artists, the best thing that they could do is fucking amend some of them contracts,” Guapdad 4000 tells Complex. “Get some people out of these deals. Get some people off the shelf. That would be crazy.”

Many artists who sign typical label contracts forfeit ownership of their own music and only receive a percentage of the proceeds made through streaming and sales. In exchange for signing some of their music rights away, artists get signing bonuses and other perks, but these payouts are often seen as unfairly low. Take Megan Thee Stallion for instance. She received a $10,000 bonus after signing with 1501 Entertainment in early 2018. While the signing bonus may have sounded like a lot of money to a young college student, Meg ultimately signed a 60/40 agreement, meaning she only receives 40 percent of her music’s earnings. She’s currently suing 1501, alleging that the contract was “not only entirely unconscionable, but ridiculously so.”

“Shit looks smooth! Got all them followers, yachts, selling out shows and shit. Come to find out, the record label taking damn near all the fucking money,” explains Drakeo the Ruler. “They’re not getting any money on the fucking albums because they fronted them all this godman money. You can be noticed all you want, but you’re broke because the record label whooped your ass.”

Producer JoogSZN, who released Thank You for Using GTL with Drakeo on June 5, says producers also “get trampled” in major label deals. “For producers, it’s different than artists, because obviously the artist is in the forefront,” he explains. “So, producers don’t get noticed, and then a lot of times, they loop you out of your contract just off of simple wording.”

Allyship

Responsibility doesn’t just fall on record labels. Artists also say allyship can also come from non-Black musicians from other genres.

Over the last few weeks, we have seen a rise in non-Black artists using their platform to amplify Black voices. Selena Gomez handed over her Instagram account to several Black artists and leaders including Killer Mike to share information with her 180 million followers. But this sort of allyship shouldn’t stop once the moment has died down.

“I would love to see more people speak up,” Guapdad says. “We all should be coming together at this time. It don't make no sense. Niggas are in the house anyway. You're not even doing nothing.”

Allyship goes beyond a simple tweet or black square, though. Open Mike Eagle suggests the best way to be an ally is through conversation.

“Allyship is not about you coming in and telling people how you’re going to help them. Allyship is about understanding the situation that a person or group of people is in and seeing how you can support them to reach those goals,” he explains. “So allyship on any front is important, as long as it's really starting with true listening, rather than people coming in and trying to dictate how it is that people will achieve their goals.”