When Virgil Abloh opened Off-White’s first brick and mortar store seven years ago in Causeway Bay, one of Hong Kong’s most popular shopping districts, he worked with Family New York, an architecture office run by Oana Stănescu and Dong-Ping Wong. As a group, they designed a store that went against every notion of traditional brick and mortar retail.

Instead of an all-glass window display and a door, the entrance is a public garden that invites passersby to sit and engage with the region’s local fauna. And as opposed to displaying products on shelves or racks with hangers, items are placed on tiered steps inspired by Hong Kong’s stone quarries, which also served as seating so the minimalist store could transform into a gallery or performance venue on a whim.

Stănescu, a 37-year-old architect, worked on this project completely through WhatsApp text messages with Wong and Abloh, and she’s helped some of today’s most creative thinkers bring their grand ideas to life. As a young architect in the 2010s she was working with clients like Kanye West, designing everything from his Parisian apartment to a seven-screen audio-visual experience for his “Cruel Summer” film premiere at the Cannes Film Festival in 2012. A few years later alongside Wong, she designed that iconic mountain that split in half and turned into a volcano during the Yeezus Tour in 2013.

But as much as we usually attribute impactful design to one architect—think Rem Koolhaas, Frank Gehry, and Le Corbusier for example—Stănescu emphasizes that the beauty of architecture is that it doesn’t come from a sole visionaire, it comes from many ideas, conversations, and collaboration. Being an open and ego-free collaborator who is able to pinpoint good ideas, listen to other creatives, and engage in great conversations about design is what’s helped her excel in a mostly male-led industry.

“I often feel like you’re there to essentially babysit a bunch of egos,” says Stănescu, who remembers going on job sites and speaking to construction workers, contractors, and project managers who didn’t take her seriously, or watching men have meltdowns over an issue with a client. “But ultimately the way I grew up and everything, I have to look at any situation and think, ‘How can I make the most of it and turn this into my advantage?’ I always find that people looking down on you or not taking you too seriously is a weird advantage because it’s on them in the end. I give them some time to wrap their heads around it because they eventually have to listen to you. And they should have the same goals as you, which is to get that stuff built as good as possible.”

Stănescu began studying architecture as a high school student and says she never knew it was a viable career option as a young girl in Reșița, Romania. “You had to be a lawyer, a doctor, or an economist in order to make a living and build a life,” says Stănescu, who was introduced to architecture by a creative friend when she was 16. Stănescu came of age shortly after Romania underwent a revolution that toppled a 44-year-old communist dictatorship in 1989. She recalls growing up in an environment that felt culturally out of sync with the rest of the world. Her father used to climb a mountain to catch a radio signal from neighboring Yugoslavia, just so he could record songs by The Beatles, which she notes was a luxury to listen to.

"You had to kind of just make the most out of what you could,” says Stănescu, when reflecting on her childhood. “So I think that attitude of looking at a circumstance, and thinking about how you can own it and what you can make of it, is something that's still kind of running in my DNA.”

Stănescu says her sense of practicality and pragmatism comes from her small town upbringing. Despite having little exposure to arts and culture growing up, she became attracted to the openness of architecture and how it could take shape in many different ways. After she graduated from the Polytechnic University of Timișoara, she kicked off her career as a student intern at the acclaimed architecture firm REX, formerly known as OMA New York, in 2006. It was her first major gig and she remembered feeling intimidated as a non-English speaker working alongside students from larger and fancier architecture schools. Although she felt lucky to be working in a young and non-hierarchical office, she said it was like walking into a library for the first time after barely knowing how to read. But it was also where she first learned the skills needed to become the collaborator she is today.

“In school, I felt like the work was very individualized. In the office, it was suddenly about putting an idea on the table, putting all our brains together to challenge that idea, and making sure it’s the best that it can be,’’ remembers Stănescu. “It meant basically putting ego aside and learning to engage in productive critique. That was a huge cultural and mental shift for me and I really enjoyed that. I was eventually given more responsibility and asked to do things that were way beyond my pay grade, which I was eager and excited about.”

Stănescu could have stayed at REX post her internship, but she wanted to learn more. So she got her “second education” by working at other acclaimed architecture offices like SANAA in Tokyo, Architecture for Humanity in South Africa, and Herzog & de Meuron in Switzerland. “The people I worked for were people whose work I was always really interested in,” says Stănescu. “So I was able to learn from the source as I was practicing in these amazing offices, which were building insane projects all over the world.” After her second education she was hired to work at OMA before leaving to run Family New York full time. While working at OMA she met Kanye West. Stănescu’s relationship with the rapper began when West commissioned OMA to design his seven-screen movie experience for Cruel Summer. “The fact that he trusted me, asking me to do all this work and join him, was huge because I was still extremely young,” says Stănescu, whose relationship with Abloh came from working with West.

After Stănescu met Wong at REX, they recognized how well they worked together and went on to launch their own architecture office, Family New York, in 2010. Founded shortly after the start of the Great Recession, the office aimed to design “productive architecture.” Instead of following early-2000s trends to design opulent architecture that was built to dazzle—like the Burj Khalifa skyscraper in Dubai—Stănescu and Wong aimed to design spaces with a larger purpose.

Aside from establishing Off-White’s retail language and building iconic stages for stars like Kanye West, they also designed things like proposals for sustainable housing complexes in Dallas that would self-generate 100 percent of their own energy. Although Wong can’t pinpoint the exact reason why they worked so well together, he says Stănescu was direct and adept at siphoning through ideas to spot the best ones.

“She’ll absorb a lot of information, do a lot of research, figure out the approach and then edit, or even wait for other people’s ideas, then filter the best one. And I think that’s really unique,” says her former partner Wong. “It works really well when you’ve got people like Virgil who are constantly generating billions of ideas to be able to work with people like Oana who could go ‘Cool, cool, cool, cool, cool, but this one’s the one.’ It’s really rare to have that kind of editing capability and that kind of clarification.”

One of the duo’s most famous projects, which has been in development for over 10 years now, is +Pool. Designed alongside the creative studio PlayLab, Inc., +Pool is a plus-shaped floating public swimming pool for Manhattan’s waterfront that would also be able to filter 600,000 gallons of river water everyday. Although the project still has no set date for completion, the group behind +Pool has been talking to New York City’s Economic Development Corporation throughout 2020 ever since the NYCEDC requested design proposals for a “self-filtering swim facility in the East River” in 2019. Although Stănescu cannot say much about its status currently, she says that some exciting developments will be revealed this year. One of the +Pool’s co-founders, Archie Lee Coates IV of PlayLab, Inc., attests to Stănescu’s ability to stand her ground as an architect.

“Architects are really good about forming a position, arguing that position and showing the person on the other side of the table why that thing is important or key,” says Coates, who also credits Stănescu for introducing PlayLab, Inc. to Abloh. “And Oana’s just so good at it, it’s almost like a lawyer, like an empathetic one at that.”

Wong and Stănescu decided to close Family New York in 2018 and Oana now runs her own eponymous multifaceted practice, which she launched three years ago. Stănescu says she hasn’t felt much of a difference running her own studio versus running one with a male partner, but Elena Schütz, the co-founder of the architectural firm Something Fantastic, who’s known Stănescu since her days at REX, acknowledges how significant that is.

“It’s quite common in architecture to work with partners just because there’s a lot of pressure and it just helps to. Oana has her own firm and that in itself is something quite special,” says Schütz. “There are as many women as men who are studying architecture and just as many, if not more, women than men who are finishing architecture school. But then, people starting their own offices and heading firms, there’s definitely more men.”

Stănescu says one of the biggest reasons for launching her own practice was because she wanted the freedom to experiment more and to uncover some “stranger” aspects of herself creatively. After overcoming a battle with lung cancer in 2017, she began to reassess what projects mattered the most to her. While her younger self would have been excited to take on whatever came her way, she now finds that one good conversation that leads to a meaningful collaboration is better than 10 different ones. “I’ve been giving myself permission to do all sorts of things and it took me a long time to get here and assume that space,” says Stănescu. “So that means doing things that aren’t necessarily architectural. I’ve been a lot more eager to adventure as an amateur into territories that I wouldn’t have dared to before.”

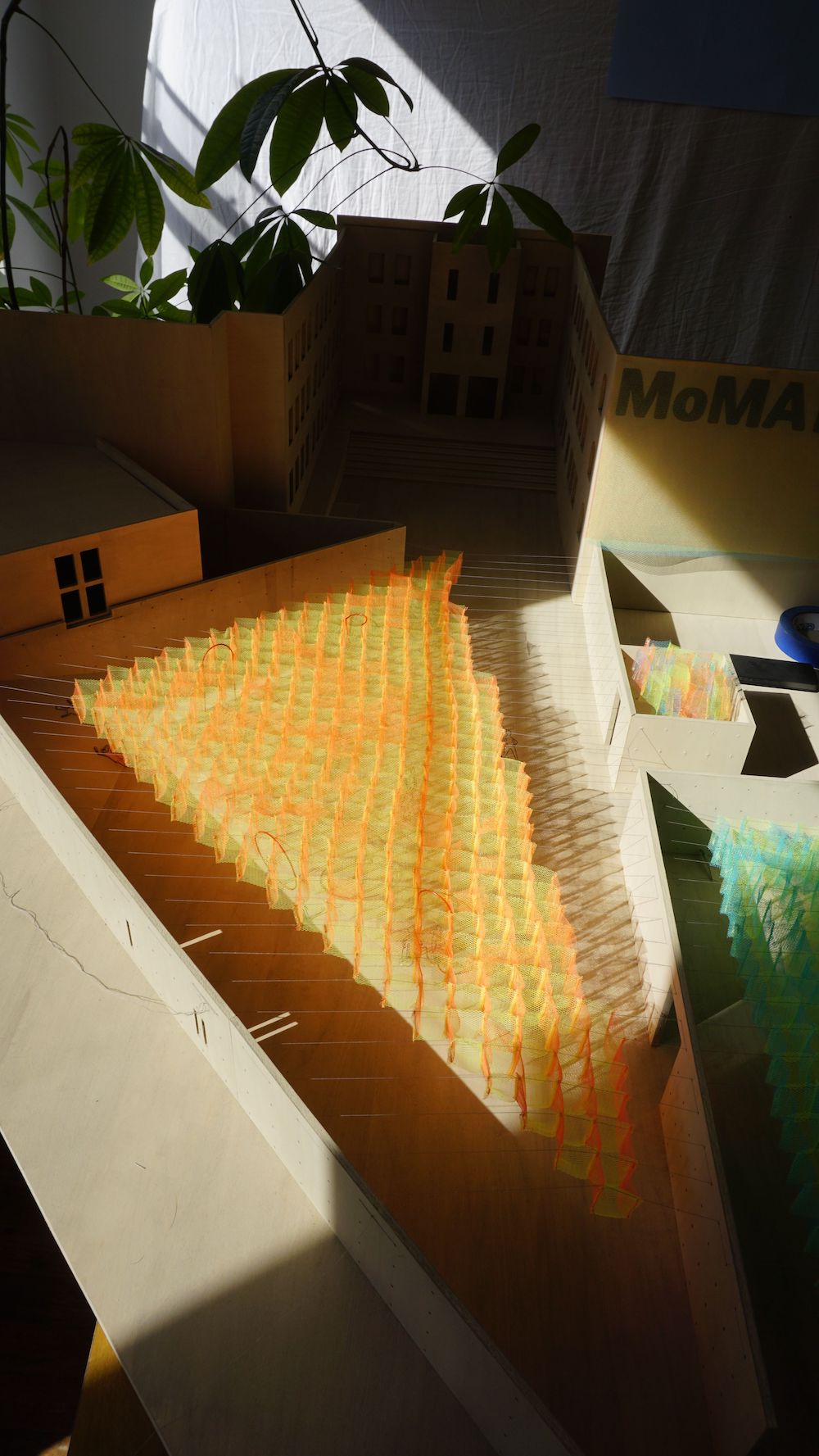

Her work continues to speak to culture and community. Although her ongoing project “Breather” and her recent collaboration with the artist Akane Moriyama for MoMA PS1 may come off to some as works of art rather than architecture, they show how Stănescu continues to push herself to do something new and redefine what it means to be an architect today. “Breather” aims to create a space where visitors can lie on an inflatable floor that replicates how lungs function under various circumstances, from yawning to coughing. Her proposal for MoMA PS1 with Moriyama, “Seriously Fun,” sought to suspend a large-scale cubic textile grid installation over PS1’s courtyard—where visitors could climb, sit, hang, and interact with the grid to change its appearance along with the natural environment. Stănescu’s ability to intersect different creative fields with architecture is how she’s inspired creatives outside her field, like Nike’s Senior Footwear Design Director Nathan Jobe, who invited Stănescu to help develop a collaborative project that never publicly materialized between Virgil Abloh and Nike.

“Throwing her in the mix with a bunch of younger designers who aren’t as accomplished as her, and her being able to chop it up with them without having any kind of ego and really getting to know the team, was insane,” says Jobe, who frequently speaks to Stănescu for creative inspiration and mentions that she was one of the first people to test Nike’s experimental ISPA footwear line—alongside artists like Tom Sachs and NASA spacesuit designers. “If you’re into design, why can’t you work on the brand team or apparel team? If you meet Oana, that’s the kind of the invitation you get, which is very similar to Virgil. The thinking is quite open and fluid and that was apparent when I first met her.”

Recently Stănescu has been busy building art installations for the next Coachella and elevated “High Line”-esque parks in her hometown of Reșița, Romania—a project that started as her college thesis in 2007, and has recently received funding from the European Union. When Stănescu is asked how she designs these incredible spaces that all seem vastly different from one another, she simply says that ideas can easily be rescaled. “I understand why they seem very different. But in my mind, the consistency lies not in the form, but in the set of goals or values behind it,” says Stănescu, whose projects could take as little as 100 days to over a decade to complete.

When it comes to starting projects, she finds it crucial for a creative exchange to occur from the start. If she doesn’t feel it’s there from the beginning, she knows when to say no to an opportunity. From there, she approaches each one with an open mind and spends time researching the site, the program, and the context the project is situated in with non-judgmental eyes. She then writes a letter to herself and her client to nail down what she thinks the full potential of the project is and why she wants to do it. She does this to hold herself accountable and make sure she doesn’t lose sight of the initial concept and drivers behind the project as it continues to develop. To visualize her ideas, she draws them out and then makes models, as many as 50 at times, at different scales, to understand how the space actually feels. After she learns how something like light interacts with certain cracks or how specific material feels, it leads to even more ideas. This process can get complicated especially when projects start getting impacted by reality—when building code regulations, budgets, engineers, contractors and more begin to play a larger role.

“For me it’s the balance between her ability to think both in and outside the field of ‘classic architecture’ that makes her stand out from the crowd and help me build and develop ideas,” says Virgil Abloh. “Her humility and objectivity, and the way she looks at the world, is unique. It leads to the creation of a deeper design, not just on the surface, but a multi-layered design. She is also constantly learning and educating others. We’ve collaborated on a lot more than just architecture projects. She and I have spent a lot of time recently focused on education through different institutions including the AA in London, Harvard Graduate School of Design, and MIT.”

Perhaps one of the most pertinent examples of Stănescu reshaping the traditional ideas of what architecture can do is the “New Spaces of Justice” course that she taught at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design last fall. A collaboration between Stănescu, Abloh, Nóra Al Haider and the Legal Design Lab at Stanford University, the course addressed the impact COVID-19 had on the justice system, which has brought forth a number of complications since courts have gone virtual. The class challenged students to rethink virtual and physical court structures and come up with solutions that would make them more human-centered and less of a bureaucratic nightmare today. This spring, the collaborative class has transformed into a studio course at MIT that will actually work closely with courts in Massachusetts to assist them in redesigning “hybrid court houses,” which will bridge technological interventions that have been implemented during the past several months to address the needs of the justice system during a pandemic.

“It’s not like, ‘Here’s my fancy rendering,’ it’s work that actually has a direct impact on people,” says Stănescu. “It’s the kind of work that actually deals, in the most direct and straightforward way, on access to justice. On people being able to reach justice.”

When Stănescu is asked what else she wants to achieve, she simply says that she’s never one to make plans because the future never ends up being what you planned for. Her most ambitious goal right now is likely relatable to yours, which is to just be able to safely spend time with friends and loved ones again. But she hopes that wherever her work takes her, she is able to continue to bridge conversations with a wide array of people.

“I still feel very much like a toddler, opening doors and constantly discovering new things that just bring so much joy,” says Stănescu. “I think that joy, it doesn’t happen often. It’s a little bit like falling in love maybe, right? It can’t happen every day or it would lose its value.”