Photographer Timothy White has been taking unforgettable portraits for decades. His subjects range from Adam Sandler to Aerosmith; Al Pacino to Andre 3000; Aretha Franklin to Axl Rose—and that’s just the A’s. If you’re ready to go down a deep rabbit hole, find the complete list (and see the photos) on his website.

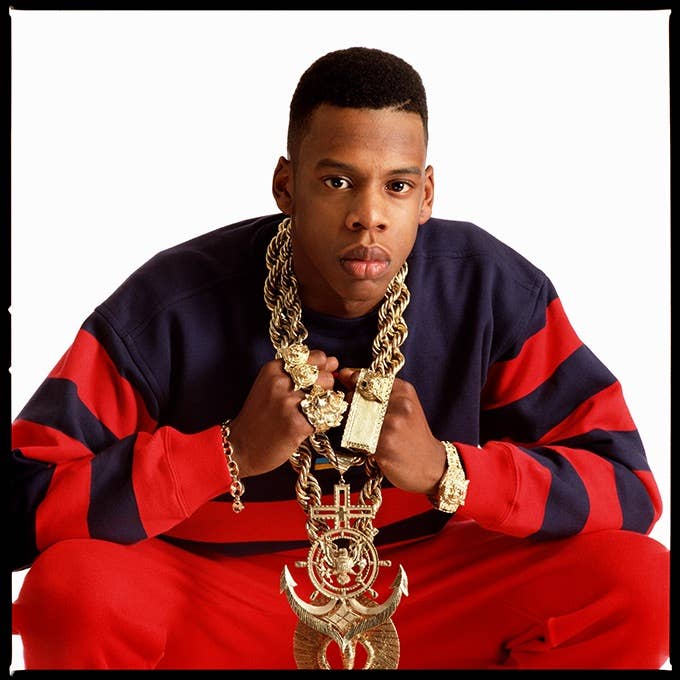

Last year, one long-forgotten flick resurfaced and gave White a whole new spin on a 30-year-old photo session. The photo, seen above, is a 1988 portrait of a then-unknown JAY-Z, still eight years away from releasing his debut album. At the time, he had a single appearance on wax to his name (High Potent’s "H.P. Gets Busy”—the Nas-mocked “Hawaiian Sophie,” where Hov makes a small cameo and appears in the video, wouldn’t even be released until the following year). Decades later, White remembers being impressed by the confident teenage JAY-Z.

In 1988, Timothy White was already well-established, having received his first big break at Rolling Stone, which he parlayed into gigs at many other magazines and record companies. We spoke with White to find out how this early-career Hov photo came to be. If you want to see the image in person, a large 30” x 40” print is being displayed as part of the HIP HOP Now show at the Morrison Hotel SoHo Gallery (116 Prince Street) in New York City.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you give me an idea of what you were doing, career-wise, when you took this photo of JAY-Z in 1988?

I’m shooting album covers and I’m doing all this stuff. I’ve got an agent in Los Angeles and all of these things are happening. ‘88 was a big year for me, picture-wise. I did Guns N’ Roses’ first Rolling Stone pictures and their first Rolling Stone cover. There were many, many others but that was a big deal to me.

I was doing a lot of hip-hop as well, and I got a phone call from a record company [EMI] to do the artist Jaz-O. I had this loft and we did some work in the studio. I rented a black panther, go figure.

Was the panther your idea?

I think it was my idea, but I don’t think my idea was to make a connection to the revolutionary group. I think it was more, “What do you have?”

Like, “You got a leopard?”

Yeah, and this guy had that. It really was a wild animal. Jaz was standing on a cyc [wall]. We built a platform and I drilled a hole through it and actually tied a chain down to the bottom so that the animal could lay down and be chained down. It was loose enough where it didn’t look like he was being pulled to the floor, but he was being held there—he couldn’t jump out and attack any of us. It was kind of weird.

So we did that, and then I went up to the roof and did some things on the roof with him and with the panther and other things.[Ed. note: a shot of Jaz-O on the roof with the panther would end up as the cover of his 1989 album 'Word to the Jaz'] Then a friend of his shows up: “Oh, hey, this is my friend JAY-Z.” JAY-Z shows up looking like he looked [in the photo], with all of that gold around his neck and the whole thing. [Jaz] told me a little background on him, that he was producing JAY-Z or working with him, and that he had named him—he had given him his moniker.

I said, “Let me get some pictures of you guys together.” I did some pictures of them together and then said, “You know what, let me shoot some pictures of him alone.” I shot a lot. There are hundreds of frames of both of them. But, interestingly, the album was Jaz-O. My database and everything read Jaz-O. And I never put it together because my career took off and I never looked back. So I had forgotten that I had shot JAY-Z—didn’t even know.

So [now] this man’s a mogul. I spent this time with him and did these really cool pictures, but I didn’t realize it until last year when I was going through my archive that I had shot this picture of JAY-Z. I went into the file and said, “Oh my god. There are some really great pictures in here.” I pulled that one out, printed it up, and hung it at my gallery in Los Angeles at the Morrison Hotel Gallery. That was on a Friday afternoon.

On Sunday morning, I get a phone call from my gallery director who said, “JAY-Z just bought your photograph.” I was like, “What? How fucking cool is that?” And then I went out to brunch and my phone was blowing up. It was from everybody who works for JAY-Z at Roc Nation, saying, “Who? What? When? Where?” Everybody forgot about this picture, basically.

He was just finishing up and coming out with 4:44, so I did a little licensing thing with them so they could help promote that last album. But that’s the story. Now of course, I go into the file and there’s a ton more pictures, but that picture kind of says it all to me. And it certainly documents a period in his life and in my life, as well as the time in pop culture history and hip-hop history.

he was a baby, but he didn’t come off as a baby. He was a really confident guy who had something going on and you could feel it. You could see it.

Did anyone on JAY-Z’s team tell you his thoughts about the photo?

It was sort of the same thing that I felt. The photo was both a part of our history that we forgot about and that didn’t really exist. It’s interesting because it really does represent something, time-wise, in the history of pop culture and hip-hop. In ‘89, I shot N.W.A., and I look back on that now and nobody has the kind of creative imagery that I have of N.W.A because after that moment when they broke, they got an attitude, basically [laughs]. They wouldn’t stand still for anybody, and almost all of the pictures are sort of grab shots in some way or the other.

When [the movie]Straight Outta Compton came out, everybody came to me for my pictures, and it was because they were unique. I had creative access to these guys before they got big enough to care. They were more excited about, “Oh my god, we’re being photographed by Timothy White for Esquire magazine.” They did what I wanted to do. “Hey, let’s go to the beach in Malibu and do some pictures there.” So when I looked at everything that came out of Straight Outta Compton, what was being asked of other photographers, there wasn’t anything quite as interesting. I think it was the same with JAY-Z. It’s so unique from that period.

When you think about that day in 1988, what about JAY-Z possessed you to want to take pictures of him even though he wasn’t your client?

First of all, he was a baby, but he didn’t come off as a baby. He was a really confident guy who had something going on and you could feel it. You could see it. He’s also got however much gold around his neck—which was real—so it was definitely interesting. “Who the fuck is this guy? What are we doing? What’s your future? What’s going on?” It’s funny because Jaz-O quickly disappeared, certainly from the public limelight, and JAY-Z appeared. The rest is history.

Do you have plans to do anything with any of the other photos from that day?

Oh, yeah. In fact, this move [Ed. note: White was moving his studio when I called] represents a big move to a new studio where we’re just digging into my archive.

I would shoot a cover for Rolling Stone magazine and I’d shoot 10 or 15 set-ups in a day. Hundreds and hundreds of frames of each set-up. Different backgrounds. Different lighting. Different clothes. But the magazine would pick one for the cover, two for inside, and I moved on to the next job. So much of it is still sitting in my archive. It’s a real rabbit’s hole. And that’s what we’re doing now—digging in and pulling things out. So I’ve actually pulled out a lot of images of JAY-Z already and scanned them. It’s just a matter of doing something with them, putting them in the gallery [Morrison Hotel Gallery] or publishing them as I move forward.

What can you tell me about the rest of the hip-hop show that’s at your gallery right now?

I put together a hip-hop show two years ago, and we did it in L.A. Part of it was, my gallery has a core business model which is classic rock, but there’s a whole new audience of people in their 40s that only grew up on hip-hop. I think that’s a really important part of who we are as a brand, but it also is our future as well. These are people that are old enough now to have expendable income to buy art. So from a business standpoint, that’s really important. It’s also a big part of what music history is about. So that’s really important, to be part of our collection and part of what we offer to the public.

I did a hip-hop show a few years ago, which was really great. I brought it to New York. I didn’t do it at the gallery. Instead, I did it at another venue and brought Darryl McDaniels from Run-D.M.C. to perform, as well as Decora, another young artist. In fact, he’s Whoopi Goldberg’s grandson.

I had him on stage too, sort of like Darryl was passing the baton to younger rappers. I had Whoopi as my guest host and Darryl as my guest host, and made a big event of it. That was really successful, so now we did another one this year with better and different pictures. There were some things that we dug out, which we hadn’t seen before, that I just loved. There are a couple of images of Biggie, who I’m a really big fan of. I love our shot of Snoop where it was just his braids and his chin and you couldn’t even tell who it was. There are a lot of great images in this new show, so I’m really excited by it.