It was 4 a.m. on December 12 of last year when the FBI came for Rakem Balogun.

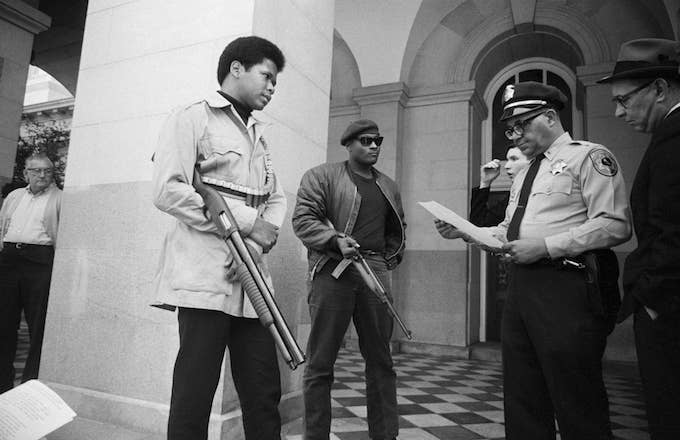

Balogun is a black Dallas-area activist with the Guerilla Mainframe organization. He’s also the co-founder of the Huey P. Newton Gun Club, which aims to “educate and arm black people in the U.S. and abroad.”

The Feds had a warrant for his .38 handgun, but that wasn’t really what they were after. The government had been following Balogun in ways both real and virtual for the prior two-and-a-half years. They saw coverage of an open-carry demonstration in 2015, and didn’t like what they claimed Balogun was chanting (“The only good pig is a pig that’s dead,” and “Oink oink, bang bang,” according to press reports).

Those chants started years of surveillance and eventually led to Balogun’s arrest. He had brought the gun on a trip out of state weeks before his arrest—in his luggage, unloaded and in a case, per airline regulations. And while Balogun thought he was licensed to bring it along, the authorities used a decade-old misdemeanor charge to determine he wasn’t. (Balogun’s attorneys are currently disputing this tactic—a trial is set for mid-May). And what did the authorities do with this clear and present danger? Took Balogun’s luggage for a day or so, gave it back (gun inclusive), and then waited another three weeks before bursting into his place in the early morning hours.

It didn’t take long before it became pretty clear that Balogun was most likely the very first person to be targeted by the FBI under their new Black Identity Extremist designation. The name is used to refer to people who, the agency believes, “in response to perceived racism and injustice in American society,” may engage in “premeditated, retaliatory lethal violence against law enforcement.” (Complex reached out to the FBI to ask if Balogun had in fact been labeled with the BIE designation, but they refused to comment, citing the fact that “the matter is ongoing”). The classification was discovered by the media in late 2017. Civil rights activists—and even former intelligence officials—railed against the new BIE classification, saying that it was an attempt to criminalize protected speech and political activity.

'Having Him Around Was a Threat to the Structure'

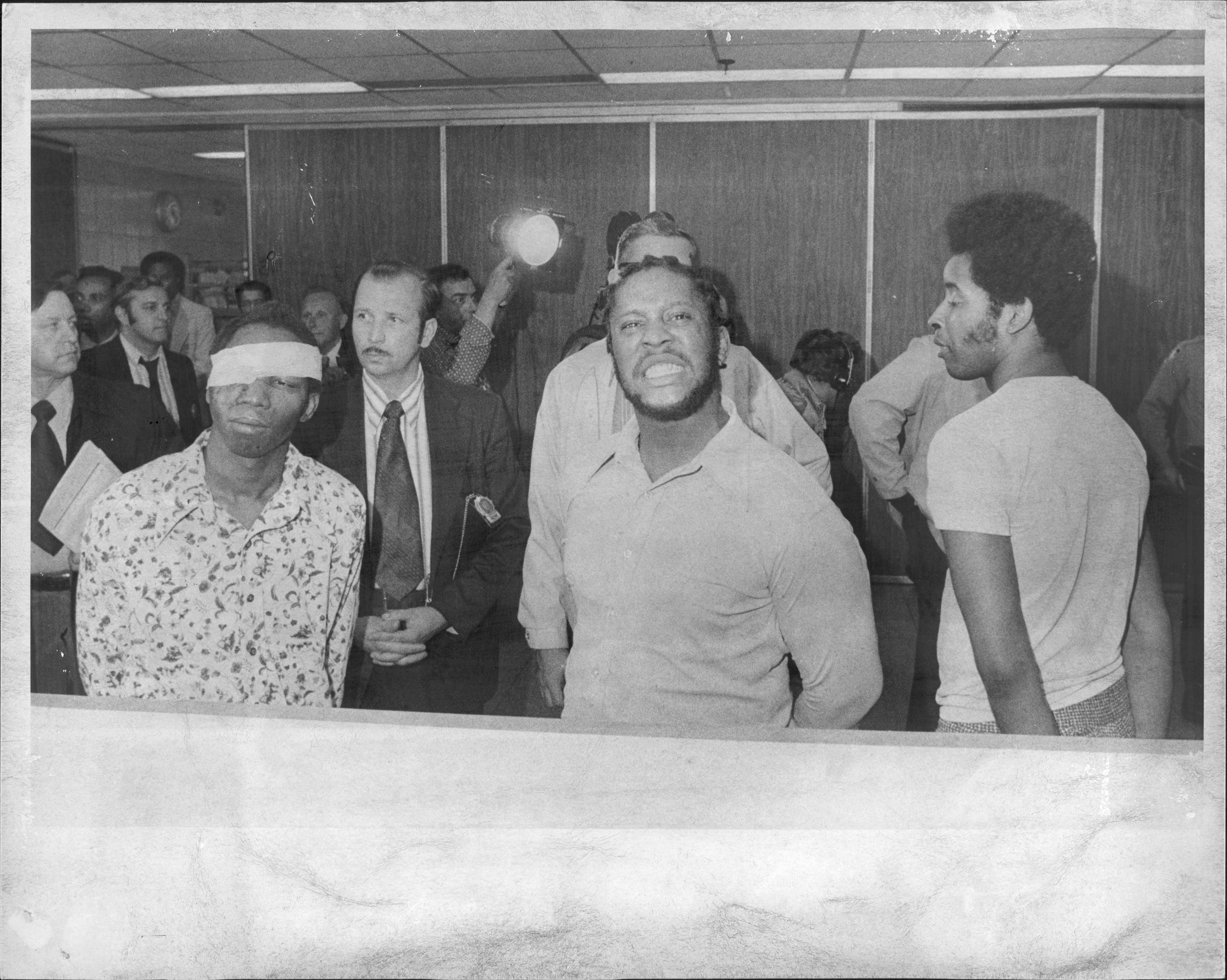

‘There Had to be Funerals on Both Sides’: The Creation of the BLA

‘Movements Had a Responsibility to Get Their Comrades Out’

‘Reading Her Book Helped Me to Feel Not Crazy’: The Legacy of Assata

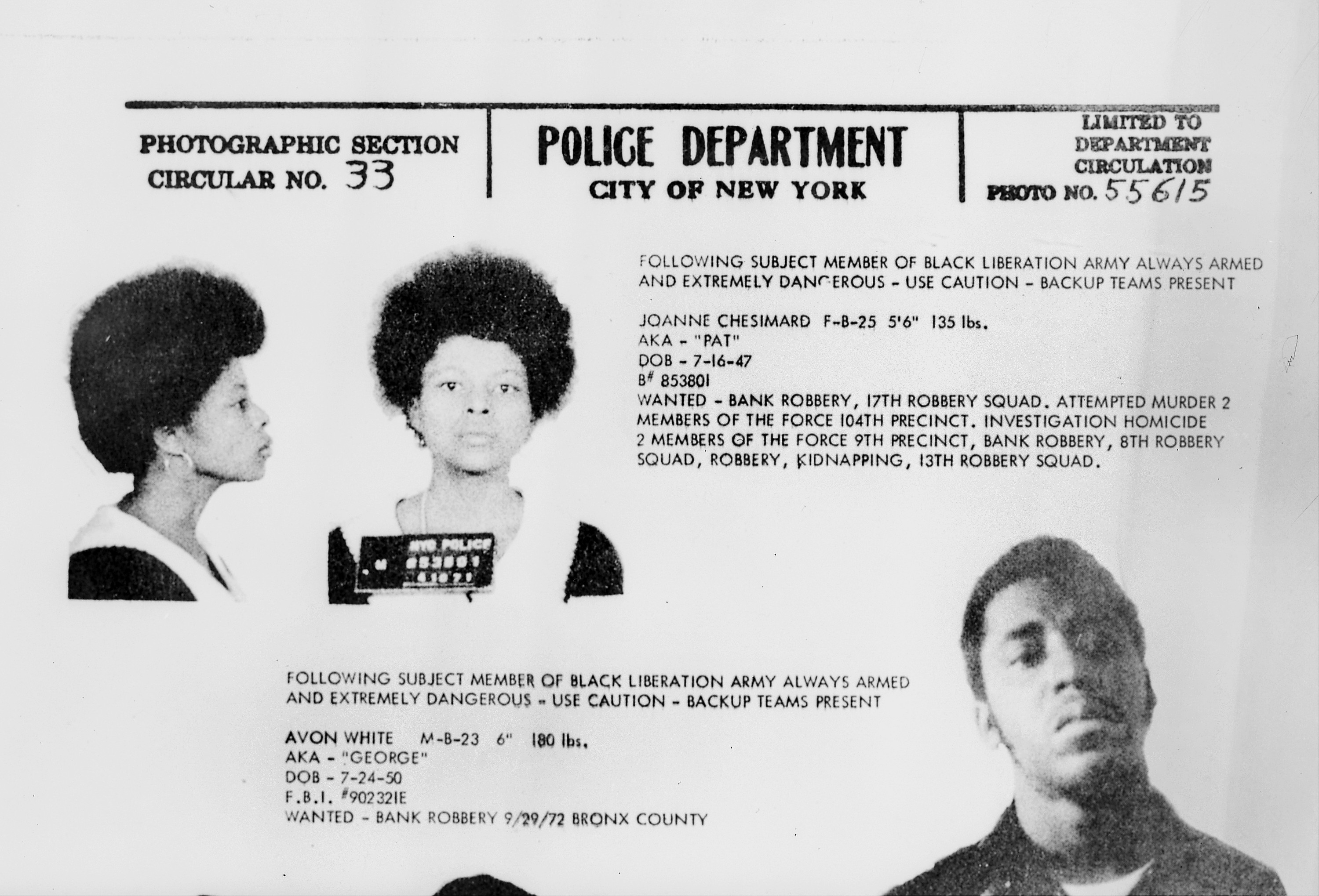

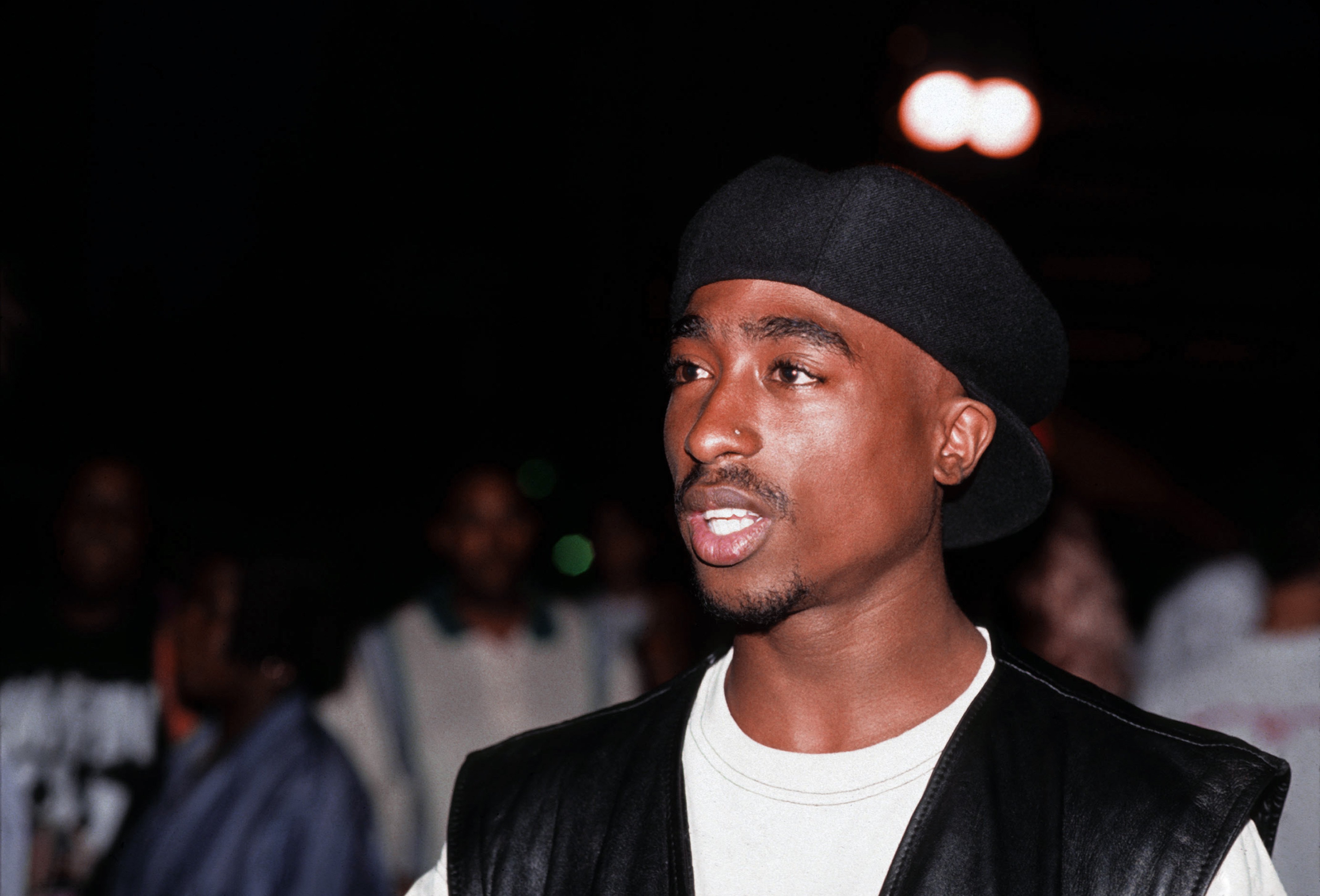

The most famous BLA-related jailbreak of all involved Assata Shakur. Shakur, 2Pac's godmother, was one of the BLA’s most notorious members, so much so that the police suspected her of being involved in every BLA-related incident where a woman—any woman—was seen. She was arrested in 1973 following a still-contentious firefight on the New Jersey Turnpike. Despite the fact that medical evidence showed that Shakur was shot with her hands up, she was ultimately convicted of murder in 1977—after, it should be noted, having not been convicted in half a dozen other cases.

On November 2, 1979, a collection of BLA members and associates known as “the Family” led a daring escape that proved successful. In the days after she gained her freedom, “Assata Shakur Is Welcome Here” posters—mocking her appearance on the FBI’s Most Wanted list—were hung from windows and carried in marches.

In 1984, after years of living underground, Assata was granted political asylum in Cuba, where she remains. The image of a black woman who fought back against police repression and remains free is a powerful one—something both sides acknowledge.

“I think [Assata] has always been a major thorn in the side of New Jersey police and the FBI because it really exposes COINTELPRO.” Berger says. “It exposes the drama of police abuse. The US had been so adamant about denying the existence of political prisoners and denying the history of political oppression in its own country. So to have a woman who escaped from prison and is granted political exile status really shows how false those denials are, and how racist both forms of violence have always been.”

For St. Louis rapper and activist Tef Poe, who was extremely involved in the movement in Ferguson after the police killing of Michael Brown, Assata’s story serves as inspiration. “We don’t have very many black revolutionaries that have actually beat the American war machine,” he points out. “We don’t have revolutionaries that have escaped the clutches of FBI. In Assata’s case, and many of her comrades, their stories offer a place of victory versus a continuing narrative of deceit, a continuing narrative of black revolutionaries going to jail or getting a bullet in their heads.”

It’s not surprising, then, that Assata Shakur has inspired many activists of this generation. One of the most active groups in the movement for black lives is even called Assata’s Daughters. The group, according to co-founder and organizing director Page May, “organizes young black people in the black radical tradition”—a tradition in which Assata plays a major role. For May and many other organizers, Assata’s 1987 autobiography was a key text in their political education.

“I was learning a lot about the true root causes of a lot of the problems in the world around me, and her book was really grounding,” May tells me. “It helped me process the grief and the trauma that comes with the moment where you start to understand the implications of anti-blackness being global and still very real and not going away anytime soon. Reading her book helped me feel not crazy. It also helped me better understand what was going on, and it gave me many examples of what resistance looks like.”

“THEIR STORIES OFFER A PLACE OF VICTORY VERSUS A CONTINUING NARRATIVE OF DECEIT, A CONTINUING NARRATIVE OF BLACK REVOLUTIONARIES GOING TO JAIL OR GETTING A BULLET IN THEIR HEADS.

“Every meeting with BLM and many other organizations, they start with a song about how it is our duty to win, how we have to protect one another, and how we have nothing to lose but our chains. [The words] were taken from Assata Shakur in the 1980’s when she was exiled,” explains Donna Murch. “Because people don’t know the history of the BLA, they don’t know that Shakur was a political prisoner turned revolutionary fugitive. So there’s already that connection there hiding in plain sight.”

One Last Mission

‘The Kennedys of Black Liberation’: 2Pac’s Family Legacy

At What Point Do We Actually Fight Back?

Members of the BLA may have inspired today’s activists in Ferguson and beyond, but their tactics by and large have not. Donna Murch attributes that to the very different—and even scarier, in many ways—political climate. She notes the existence of the Patriot Act, indefinite detention laws, and a seemingly never-ending War on Terror.

“The country is infinity more repressive than it was in the 1960s,” she says. “The kind of activism that not only the BLA but the Black Panther party engaged in—which is armed self-defense, police patrol, the legal use of unconcealed weapons, and carrying them as a symbol of their right to prevent state violence—that’s unimaginable today. Armed rebellion and armed struggle given the whole modification of laws over the last 60 years is very dangerous for black people.”

Tef Poe, who tells me he’s constantly wrestling with the question, “At what point do we actually fight back?”, saw the beginnings of armed resistance in Ferguson.

“I saw what that looks like,” he explains. “I saw what happens when the gang bangers meet and formulate a truce and decide that tonight, when the police try to enforce the curfew, what happens if we don’t go in? What happens if, when they bring out their guns, we bring out our guns? And what happens if, when the helicopter comes across Canfield [Drive], what happens if we shoot at the helicopter? Many people would suggest that that’s insane, but seeing the militarized police force five minutes away from my mother’s house, seeing buildings and schools that I grew up in inhabited as safe houses for people in the community that were protesting, and seeing teenagers walking around two summers with gas masks on, I would suggest that it’s not insane. I would suggest that it is very logical at that point.”

“The BLA produced Pac and then Pac produced the Ferguson generation. It’s a continuation of the same resistance that has been going on since the days of the slave ships.”

Page May makes sure to teach the young people in Assata’s Daughters about the BLA so that they can be aware of the complete history of black resistance.

“We are concerned with our young people understanding the history of what has come before them, both in terms of how did we get here, and also what have our people done and what worked and what didn’t,” she explains. “We’re not trying to say this is how we’re going to get free—because we don’t know—but we want to make sure young folks understand all the different ways that people have fought back, because that’s not what you learn. You don’t learn about the ways that black people actually ended slavery, and you don’t learn that the non-violence of the civil rights movement was a strategy. For some people it was also a morality, but we study it as a strategy and we can compare that strategy to the strategies of groups like the BLA without making moral judgments about it. We can talk about why the strategy shifted, did it need to shift—we can have those debates and young people can decide for themselves what they make of it. We have a conversation about the tactics of the BLA as a part of a conversation about power and how we’ve challenged power.”

Stand Up, Fight Back: Reckoning With the BLA’s Legacy