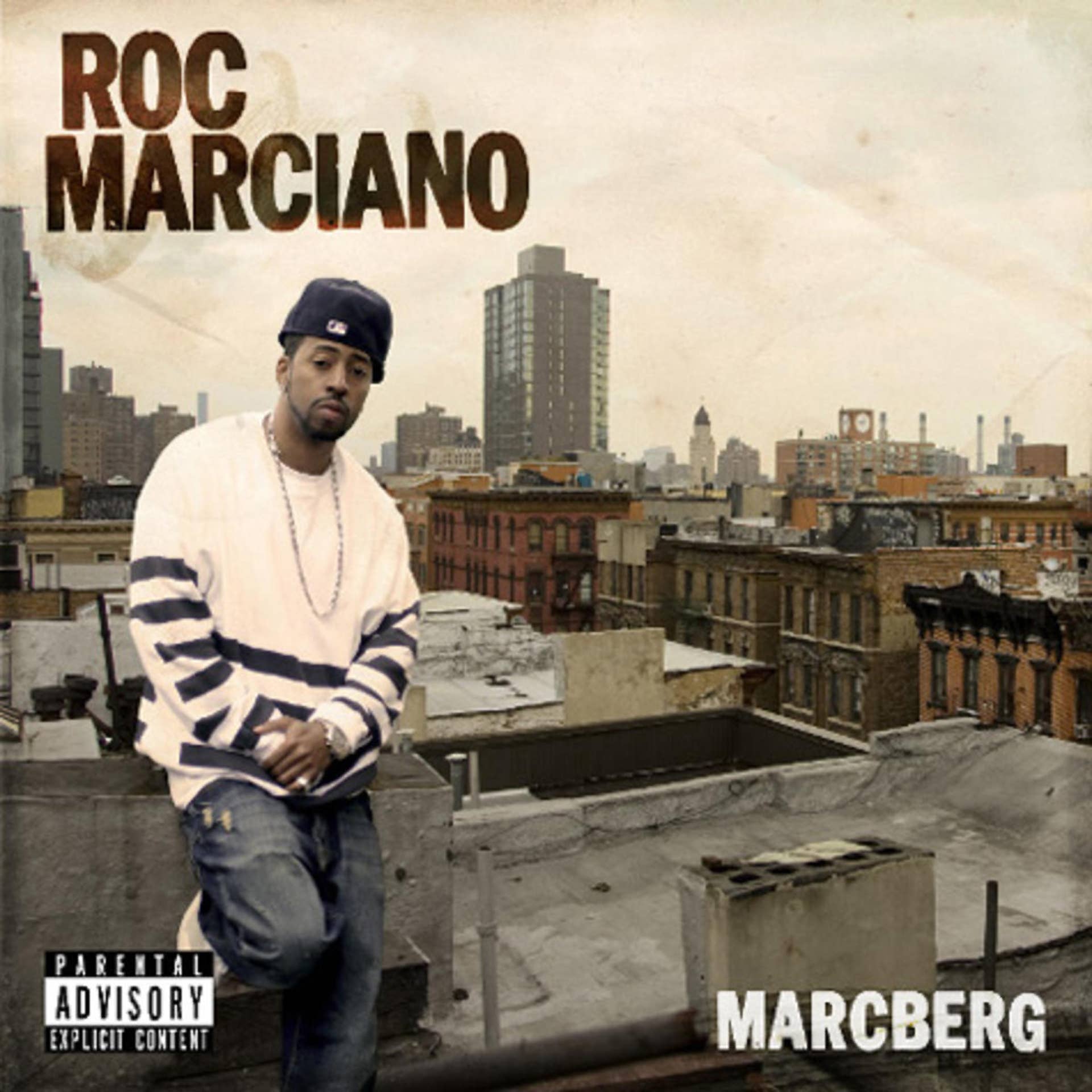

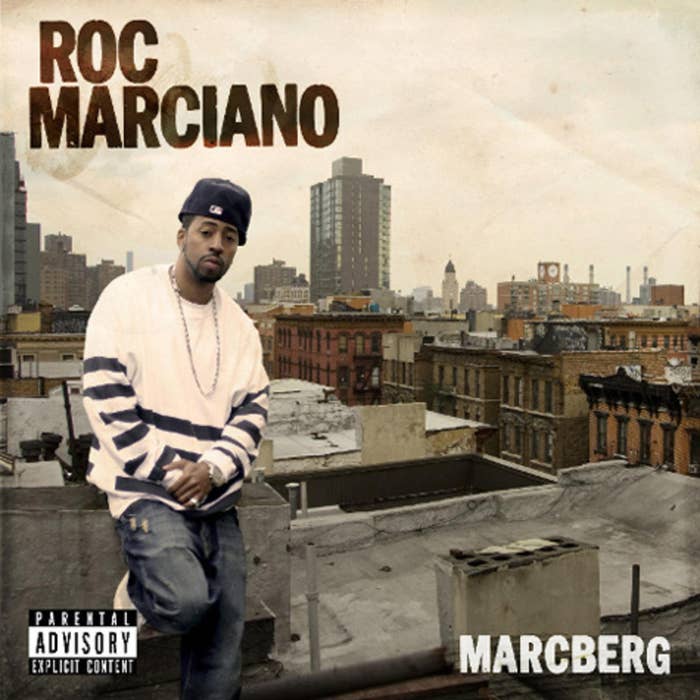

“Marcberg still sells.” That’s what Roc Marciano told me over plates of crustaceans at John’s of 12th Street in New York’s East Village in early 2019. A decade after its release, Roc’s debut album Marcberg has proven to be one of the more influential rap recordings this decade. The album helped revitalize a sound some thought was dead. It’s like he dusted off old scriptures and used them as a blueprint to write his own, making the East Coast remember its sound again. “I’m the Godfather,” he says now, reflecting on his influence.

Around 2010, New York rap was in a transition period, as the old guard had become wildly successful and mainstream. There was a growing appetite for new blood that could carry on the energy and sound that the JAYs, Nas’, 50s, and Dipsets delivered during the primes of their careers. New York was sounding like everywhere else and needed a shot in the arm.

Enter Marcberg.

It’s an album that came out of nowhere, from a former Flipmode member that sounded like nothing else at the time. In the years immediately following its release, I remember hearing folks talk about this album like it was the game’s best kept secret. And when I finally gave into my curiosity, I was blown away by finally finding what I had been looking for. From top to bottom, Marcberg is a showcase of lyrical prowess and expertly crafted production, and its DNA can be heard in the music of many New York-area rappers who came after. From ASAP’s come-up in 2011 (Yams was a big Marci fan) to 2013’s Polo Sporting Goods by Retch and Thelonious Martin to Griselda, Marcberg emboldened a crop of rappers to lean into their East Coast roots and be themselves.

At the time, the gritty hellscape that Marcberg captured was considered to be underground. But now, with the success of Buffalo’s Griselda crew, the sound is starting to bubble over into the mainstream, just as the likes of Wu-tang and Mobb Deep did before them.

Celebrating the 10-year anniversary of the album, I got on the phone with Roc Marciano to talk about making this seminal masterpiece, laying the groundwork to become a sustainable independent artist, and how he plans to top these last 10 years in the next decade.

Do you remember the moment you knew what the sound of Marcberg would be?

At the time, I felt like the music I loved was lost. I wanted to make an album that spoke to me. I also wanted to put my best foot forward and show what I could do. It’s funny because me and Alchemist were talking about it recently, and he was like, “Yo, back when Mobb Deep was popping and New York rap was at its height, I felt like I was nice then, too. I felt like I could’ve participated in that era, too, but I missed [it].” So when I got a chance to actually do Marcberg, I felt like this was me coming in and adding my piece to the game. That’s what the creation of Marcberg was for me: it was like a chance to actually add my two cents in.

Were you worried that this wasn’t going to hit?

To be honest, I didn’t care. It was just one of those situations where, when I came into the game, everybody was doing it a certain way and I felt like I tried that. I tried coming in, working with the hot producers at the time. I just felt like I was going to fall on my own sword if was going to go out. So I really didn’t care how it was received. I just knew it was good. If they were going to accept it or not, that was a whole different story.

“I wanted to make sure that it would measure up next to other shit I felt was classics. That album is bulletproof. I love all those tracks. It ain’t nothing weak on there.”

In your Rap Radar interview, you said that you were the catalyst for this new underground sound. Talk about how you saw your influence grow over the past decade.

Man, what can I say? It’s 10 years in the making. It’s just a constant punching of 10 years, and embracing other artists who are actually good at it. So I really think it’s just a matter of time before people really catch on to something. Because if the art is good, it’ll continue to thrive. There is probably nobody from my era or age group still active besides Hov. There ain’t many artists who put out projects 10 years ago that people really even care about right now. How I feel about it is: after 10 years in the making, it’s about time.

Marcberg reminded me of Queens rap like C-N-N and Mobb Deep, but you took a more minimalist approach. You’ve said that people didn’t like some of your tracks at first, because they didn’t have drums. Why did you take that approach?

I wanted things to complement my voice and my style. I wanted music that would make me the feature. I didn’t want beats burying my rhymes—these big, loud tracks where you can’t even hear what the person is saying. And it ain’t even about what you're saying, it’s about how good the beat is. I wanted to make shit that would showcase my talent. It’s just really making what I feel, from the heart. That’s not my only bag, but I like minimalist music.

In your early tracks with Pete Rock and Busta Rhymes, the subject matter was more or less the same, but you were rapping faster. It seems like you wanted to slow your flow down for Marcberg.

Yeah. Also, you have a period of time where you’re finding yourself as an artist. A lot of that stuff we were rapping to at the time [were] those big, loud beats. It’s not like I’ve got this big, heavy baritone voice. So a lot of times those beats are bass-y like that, and then on top of that, you’re working with all types of people, and you have to speak up and defend yourself. It’s not like you can be like, “You know what? I’m going to get my own vision across,” and just chill out in your comfort zone. If you come to the studio and fucking Canibus is in there, you can’t be chillin,’ especially when you’re new in the game. You’ve got to talk the fuck up. Not to mention, I was just taking the tracks as they were giving me. So [the change in flow] came with growth.

Did you work on the album entirely by yourself? Who else was involved in helping you craft this masterpiece?

For most of the beats, I was out digging with Large Professor. Large was taking me out to a lot of ill record digging spots because I’d never really been to no real digging spots besides trying to run up in a local thrift store and trying to snatch up records. I did a lot of the recording at my man D.O.A.’s crib [D.O.A. receives a “recorded by” credit on nine of Marcberg’s 15 tracks], and I did a lot of recording at Electric Lady Studios and we mixed in there, too. That was pretty much it. I had all the homies around me. I had my man Lasandro with me around that time; I had my man Dino Brave with me; I had my man Knowledge [the Pirate] with me around that time. I wasn’t alone in my sessions. I definitely enjoyed making it.

“A lot of cats caught bids and died in the streets and stuff like that. So [I was] trying not to fall into that category. I think the album reflects that.”

Do you remember how long it took you to make the album?

It took about a year to make it. But some of the samples that I had, I had for quite some time. I was holding them to the side, like, when I do my album I’m going to keep these. When it actually got down to creating the project, I got a deal on SRC, Steve Rifkind’s new label after he shut down Loud. So they cut me a check and I went to work on it.

Do you remember a couple of those?

I remember a couple of them. The title track “Marcberg,” I had that for a while. “We Do It” with Ka, I had that sample for a while. What else did I have for a while? Man, so many. I had “Raw Deal” for a while. I had “Hide My Tears,” too, for a while. I had about four or five of them that I knew would be big parts on the album.

Was there any beat that stood out to you? One that was like, “Aw man, I’m going to kill motherfuckers with this shit”?

I knew when I did “Snow,” and then I did “Thug’s Prayer,” “Pop,” [and] “Don Shit.” I knew it was special, because I A/B’d this album against a lot of albums I grew up loving. I would play my album next to albums I loved, track for track, and I knew my album was hanging with them shits.

Like what?

I would A/B it next to fucking [Only Built 4] Cuban Linx. I would A/B it next to Illmatic. Track for track—of course I would lose on a few tracks—but I would be like “Yo, I’m there, I’m right there.” You could play that and then you could play this and be like, all right, ain’t no fall-off. I would play my album and listen to other stuff that I really loved and be like, “Okay cool, I did a damn good job.” I knew that.

Were you trying to capture the feelings those albums gave you?

I wouldn’t necessarily say that I was trying to capture those feelings. I just wanted to make sure that my shit was bulletproof like theirs was. I was trying to do my own thing. I took it back to the basement, to what I was doing as a kid. When I was a shorty, I was making my own beats or coming to the studio with my own sample ideas and things of that nature. So this was an opportunity to get back to that. It was an opportunity to do shit my way. At the end of the day, I wanted to make sure that it would measure up next to other shit I felt was classics. That album is bulletproof. I love all those tracks. It ain’t nothing weak on there.

I was watching an interview you did in 2010 with Dallas Penn. He mentions songs like “Thug‘s Prayer” and “Hide My Tears” that have these highs and lows. Talk about why you wanted to have that kind of perspective.

I mean, you can’t hide what you are. At the time, I was broke, so I’m speaking to the times, telling my story. You’ve got to tell the victories, and you talk about the losses, too. And it was a weird time in the game. Hustling and crack was phasing out—the streets wasn’t a feeding frenzy like it used to be. A lot of cats that came up from my era was trying to figure out what they was going to do next. A lot of cats caught bids and died in the streets and stuff like that. So [I was] trying not to fall into that category. I think the album reflects that.

2010, that’s when weed really started taking over.

Yeah. Weed canceled crack out. It was a strange time.

One of my favorite lines is, “I’m like Tony in the silver Carrera/They don't build them no better.” Do you have any favorite lines from Marcberg?

I'm not one to be tooting my own horn like that. I don’t even remember all of them now. I rapped crazy on that, even from the gate from [the album’s first song after an intro] “It’s A Crime.” Pick a line. I'm rapping crazy all over it. I really don’t have no favorite lines. The rhymes off of “Raw Deal,” the rhymes on “It’s A Crime,” the rhymes on “Don Shit,” fucking “Thug’s Prayer,” they’re classics for a reason.

What was behind the pimp theme? You started the album with “Pimptro,” and you’ve run with that theme throughout your music.

It was another hustle that I was familiar with. The pimp stuff always spoke to my spirit. I felt like everybody had their niche: people using mob movies, they would use this, they would use that. I wanted to highlight stuff that I found fun and interesting—things that piqued my interest. That’s what it was about. I thought it was real good stuff. Good content.

Why did you choose the name Marcberg?

It’s just a play on my name. I wanted to come out with the Marcberg pump [note: Roc is punning on Mossberg pump-action shotguns]on niggas, interrupting the party—boom, this shit is done. So Roc Marci, Marcberg, you know what I’m saying? That’s what I was thinking when I named it Marcberg. I come in with the pump, fuck the party up.

You make this album, and it’s a critical darling. Did you feel any pressure to follow it up with something else great?

Yeah. There was definitely some pressure there, because in between making Marcberg and Reloaded, I had a son. I had to provide for another life. It wasn’t pressure in terms of being able to do it again—it was more or less like, time to go back to work and go all the way.

When you’re creating your first album, you wrap up your life up to that moment. That’s how you create your album: your whole life went into the first album. So now the next project was like, how do I collect enough fly beats? I don’t have a lifetime to collect these beats now. There’s anticipation now, too. So that’s pretty much what it was about: I just wanted to make sure that I could gather up enough fire beats like I did for Marcberg.

There’s people who like Reloaded a little bit more than Marcberg. I go back and forth. Do you have a favorite?

Nah. I love them both. Around that time I made Reloaded and I was listening to it, I knew I grew as an artist. I was a better rapper. I liken it to Nas' first album and his second album: Illmatic versus It Was Written. He was crazy on Illmatic, but It Was Written, he was a better writer.

He was an artist.

He was a more polished emcee. The first album was the rawness. The second album, the writing was on another level, even if you didn’t like the production as much as Illmatic. That’s how I felt like I did on the second album. Just like Biggie. Not to mention myself with these guys, like I feel like I’m Nas or Biggie—I’m just talking about the progression between albums. You hear the young, excited, aggressive Biggie on Ready to Die. On Life After Death, you hear this cool motherfucker, this more confident rapper. I felt like that’s what happened with me on Reloaded. I was way more confident as a writer and as a producer.

After dropping all these great albums, do you still want to stay independent?

Oh, yeah. I’m not pressed for no deal. Once you decide to actually take these deals, it can get weird with your freedom—being able to put out product when you want to and stuff like that. I really don’t care for having too many chefs in the kitchen. I’m listening to what everybody has got to say, I’m taking meetings. But as an independent artist, I’m doing very well.

“I’m the Godfather. If I stamped it, it’s going to go.”

Has it been difficult for you to get to this point? I'd imagine it was kind of a struggle, at least early on.

Hell yeah. Those first couple of albums, those were sacrifices, but it ended up paying off in the end because I own these projects. I only did licensing situations and shit, but I own the masters, so eventually the masters ended up coming back home to daddy where they belong.

And I can’t even lie and sit down and say I drew this play up from the beginning, because for a while I was trying to figure out how to create a business model that would allow me to continue to make the kind of music that I wanted to make, and be able to thrive. That was definitely a challenge. I was building this new lane, you know what I’m saying? Putting in a lot of work and not being able to really receive the benefits from it. Once I started the Rosebudd's Revenge series, I decided to change my business model and God is good, it worked out.

Yeah, I remember that. That’s when you put it on your site first [Roc’s albums beginning with 2017’s ‘Rosebudd’s Revenge’ were initially released exclusively for sale on his own website for a period of time, before becoming available at other retailers and on streaming services]. OK, let’s get into what you’ve got going on now. You’re getting into artist development with Stove God Cooks. What has that process been like?

I met him through Lord Jamar and Busta. I just knew that dude was talented. They’ve been seeing how my albums have been doing—the critical success. It’d be amazing if I can take an artist that’s unknown and turn that motherfucker into somebody overnight, you know what I'm saying? I knew he was a talented dude. We just had to capture it. I knew if we could pull this off, it would be something special. So we started off [and] the first couple of tracks were fire. I kept feeding him more, and there you have it. It wasn’t no crazy plan. I knew I had some production for the brother, and I knew that if he did what he was supposed to do, we would put him right on the fast track.

I was kind of surprised at the reaction that it got, you know?

You were surprised that the reaction was good?

No. Just that it caught on so fast. People supported it from jump and I—

You would be surprised that something I put my word behind, that people would support it from the jump? That surprises you? Anything I stand on, people support it, bro. If I stand on it, it don’t mean I just got featured on it or I did a beat for you. If I’m posting the shit and I’m telling people, “This is the guy,” he’s going to have a following immediately.

“We did the 10-year thing, now I’m reinventing myself once again. This next 10, we’re going to do it big again, man.”

I understand that. But I started seeing other people from other outlets supporting it that wouldn’t usually support. I was just kind of surprised at that. I feel like the tri-state area is kind of embracing that wave. We’re proud that we have a wave and a sound again.

You crazy, Angel. I’m the Godfather. If I stamped it, it’s going to go. Now, if it’s not good work, then that’s something different. But you know I’m the Godfather.

He’s the new wave. He's a younger artist, so he speaks to a younger crowd. But I knew that’s what this lane needs. This lane needs new, young niggas. It don’t need more old niggas. I can go out and go do albums with niggas that’s 35, 40 years old, but what’s that going to do for the culture? Another 40-year old nigga on stage telling coke stories and shit? They need somebody in their 20s doing it. We need to expand this shit and make it bigger and better. That was my vision with this.

When you talk to Cooks, he’ll tell you himself: when we did this album, I told him it was going to pop. Then it came out, [and] I’m hitting niggas up, laughing, like, “What’d I tell you?" Cooks is like, “Yo, you did not lie at all. You said exactly how it was going to go.” Because I know. I know music.

Are you looking to develop more artists?

Definitely. I'm looking to do a lot more of that.

And your right hand man Ka just dropped an album. We always talk about you having these projects just tucked away, like one with [Roc and Ka’s duo]Metal Clergy. Is that record happening this year?

We’re going to try. It’s all a matter of sitting down and doing it and collecting the vibes, because we’ve both grown a lot since our first projects. When people start to get into their zone, sometimes it’s not easy to meet in the middle and find beats that we both love. So it’s not as easy as it might have been eight to 10 years ago. Ka is on some total different shit right now. If you listen to Ka’s album, you can tell his style has gotten even more sparse with his sound.

Yeah. I was going to say “dark.”

Yeah, exactly. Usually tracks that I’m in love with, Ka is like, “Nah, I love this one.” So we'll see. Either way, we got more records together. If it happens, it happens.

You’ve been releasing albums back-to-back since 2017. What should we look forward to from you?

I’m on vacation. I just produced Stove God’s shit. New music is getting ready to come. We did the 10-year thing, now I’m reinventing myself once again. This next 10, we’re going to do it big again, man. I’m definitely going to be doing more producing. That’s how I'm starting my year off.