June 22, 2019, marked the first Windrush Day on the anniversary of the HMT Empire Windrush bringing Caribbean migrants over from Jamaica to the United Kingdom in 1948.

Passengers on the first voyage to the “mother country” included a few notable people: Sam King—a Jamaican ex-serviceman and first black Mayor of Southwark—helped Claudia Jones organise the Notting Hill Carnival, and Alwyn Roberts, the calypso legend from Trinidad (also known as Lord Kitchener) sang “London Is The Place For Me” upon arrival at The Tilbury Docks, Essex, in 1948. Of the reported 492 people aboard the ship, more than half were from Jamaica, with the rest mostly from islands like Trinidad and Bermuda.

They initially came to help rebuild the country after World War II, but optimistic migrants were met with unwarranted hostility and harassment from English people. White homeowners with “room to rent” signs in their windows would often refuse blacks, the Irish, and people with dogs. Likewise, few nightclubs were available to black people. As a result, the blues dance (or shebeens) were usually held in the basements of their homes, or “captured houses”/derelict spaces. Despite all of this, descendants of the Windrush Gen would go on to build legacies that would change this country forever.

Music played a pivotal role in reuniting the community on new shores. 50 years ago, Desmond Dekker’s “Israelites” became the first reggae song to enter the UK singles chart at No. 9, and in the summer of ‘78, Althea & Donna’s “Uptown Top Ranking” was the first deejay song to hit No. 1. The deejay style—popularised by U-Roy and his chanting over riddims—had now crossed over. Other early adopters, such as Tapper Zukie and Dennis Alcapone (Stefflon Don’s uncle), soon relocated to the UK.

View this video on YouTube

The only good system, is a sound system.

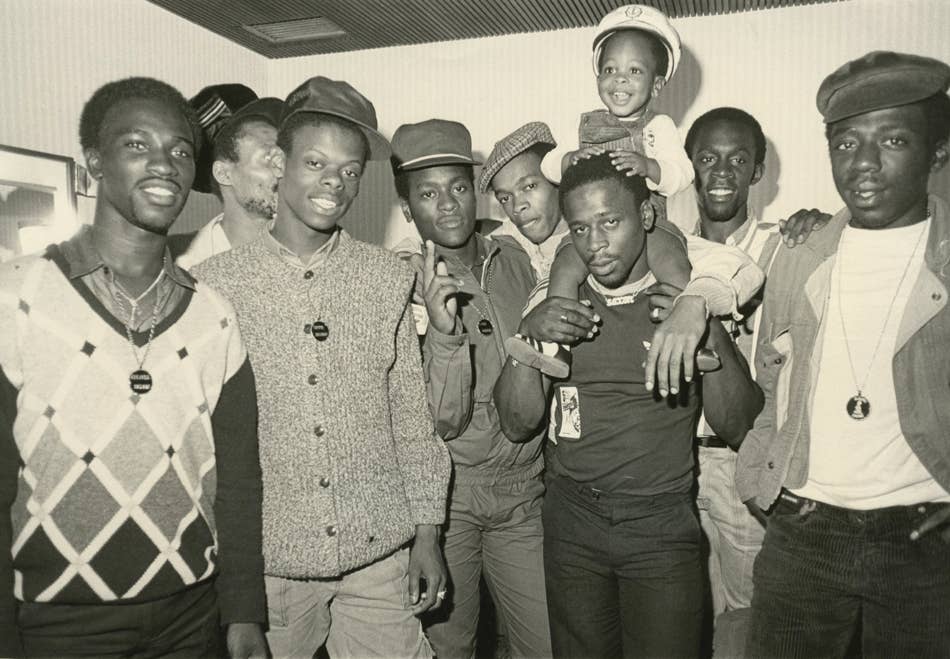

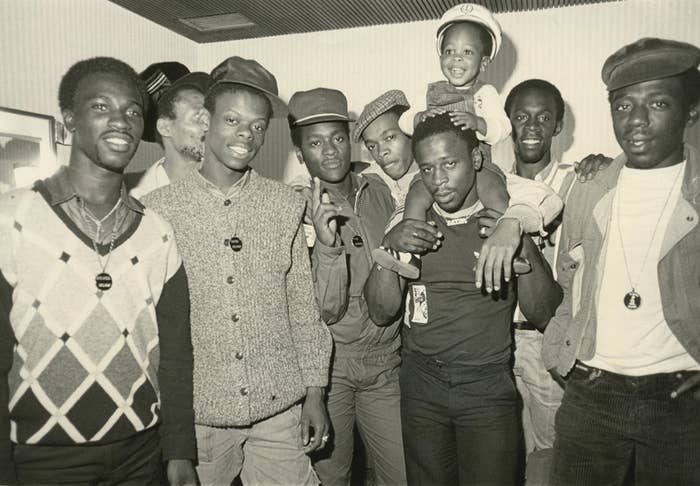

Saxon Sound are arguably the most innovative British soundsystem. The Lewisham-based sound boasted global chart-topping singer Maxi Priest and culture-shifting deejays Smiley Culture, Peter King, Tippa Irie and Papa Levi. And together, Saxon drew the blueprint for British mic-controllers. “We wanted to have our own identity,” Tippa Irie tells Complex. Peter King introduced the “fast-chat” style, while the first UK deejay to top the Jamaican charts was Papa Levi with “Mi God, Mi King”. “We made Jamaica start to follow what we were doing,” adds Irie on the impact of cassette tape recordings of Saxon’s dances.

Tippa Irie went from sneaking into his father’s blues parties to picking up the mic, inspired by Jamaican icons Brigadier Jerry and Josey Wales (rapper J Spades’ dad). Prior to being scouted by Saxon’s owners, Musclehead and Dennis Row, Tippa—the son of a greengrocer raised in a pre-gentrified Brixton in the ‘80s—almost became a plasterer. Eventually, his path would lead him to perform on the famous Reggae Sunsplash stage. Saxon deejays were also the first to share their British experiences in cockney and Jamaican patois. “When you’re at home with your parents, you speak patois. But when you’re on the road with Tom, and Tom comes from Stratford or East Ham, you speak like Tom,” Irie explains. The late Smiley Culture was first to perform it in a dance, most notably on “Cockney Translation” and most successfully on his Top 20 hit, “Police Officer” (Tippa himself used it on “Complain Neighbour”).

Everyone from UK hip-hop pioneers Rodney P and Roots Manuva to jungle/drum & bass MC Skibadee—and many others in between—cite Saxon Sound as inspirations. But before acts like Apache Indian, Pato Banton and Bitty McLean scored Top 10 singles in the ‘90s, they learnt their trade on soundsystems outside of the big city, like Birmingham’s Quaker City and Wassifa. At the peak of the competitive ‘80s, Clapham-based Sir Coxsone Outernational Sound played host to top-ranking deejays Super Cat and Nicodemus. World Record holder Daddy Freddy, Reggae Reggae Sauce’s Levi Roots and producer/shop owner Blacker Dread worked on the sound too, the latter going on to produce Jah Screechy’s “Walk & Skank”, which was famously sampled for SL2’s hardcore classic “On A Ragga Tip” (which peaked at No. 2 in ‘92 on XL Recordings).

What happened exclusively in blues parties was now accessible to wider audiences through the clubs and pirate radio. A cassette tape recording of a Unity Sound dance led to Deman Rocker being sampled for the hardcore track “Lamborghini”, which dropped on Shut Up & Dance Records in 1990. Deman also wrote the socially-aware “Ragga Trip” following the overdose death of schoolgirl Leah Betts. Formed with his brother, Flinty Badman (both born to Montserratian and Dominican parents), The Ragga Twins entered a UK dance music landscape without emcees, gun-fingers, and wheel-ups. “They didn’t know what a reload was when we came over there,” says Flinty. “The few black people that were going, they understood what was going on. The rest of the crowd would be like, ‘What the fuck’s going on here? Why has he stopped the tune?’” Flinty and Deman were also early witnesses to the rise of jungle. “The more the reggae samples came in, the more people who were going to reggae dances and hearing these things were like, ‘Yeah, mate, I can go to them dances ‘cos I know that tune from the reggae days,’ and that’s how it built up,” Flinty remembers.

View this video on YouTube

Junglist massive!

Veteran junglist General Levy, born and raised in North-West London to Trinidadian parents, spent much of his youth raving to the likes of Jah Shaka, Sir Coxsone, Saxon and Unity Sound. Those formative years observing greats before him helped when honing his skills. “Incredible”, one of the biggest jungle tracks of all time, came to fruition as a result of Levy’s sound-boy roots. “I did ‘Incredible’ as a dubplate,” The General admits (in short, it wasn’t made for wider release). “I went into the scene as an established reggae artist who had won reggae awards; when I looked at jungle, I was just giving a strength to the scene. I had no idea is was going to overwhelm the whole of my reggae career.”

However, it didn’t come without naysayers. Some reggae fans found it too weird and electronic, while most dance music fans didn’t appreciate emcees. “People aren’t used to change,” says The General. “They’re used to what they wanna hear, so when they hear something different they’re disappointed.” Jungle made a little bit of splash back in Jamaica with Dave Kelly’s “Backyard Riddim”, but nothing more than that.

Masters of ceremonies.

By the late 1990s, Heartless Crew were dominating clubland as a UK-born soundsystem. The multicultural crew—made up of DJ Fonti and MC Bushkin of Caribbean descent, and MC Mighty Moe of Middle Eastern heritage—was raised in house parties and community halls, where they first learnt how to control crowds with their selections and hosting. Bass Odyssey, Black Kat and Killamanjaro, as well as UK dancehall outfit Glamour Guard, helped to shape a young Bushkin. “Jamaican sounds knew how to entertain the whole night,” he says. “They had to have a bit of everything for everyone.” Heartless’ diverse selection matched the tastes of predominantly second-generation, Brit-born Caribbean ravers.

“Crew” eventually replaced “Sound” in name, but the foundations laid in the ‘80s were firmly set. The rise in “Crew” name also coincided with Jamaican equivalents such as Scare Dem Crew and Monster Shack Crew; grime crews such as More Fire, Slew Dem and Roll Deep took their names from songs by legendary artists Capleton and Beenie Man.

Before Sticky and Ms. Dynamite’s 2001 hit “Booo!”, dancehall-leaning MCs Richie Dan and Top Cat (who scored the first UKG Top 20 with Double 99’s “Ripgroove”) spat on more conventional garage beats. Another MC inspired by dancehall, Stush, didn’t gel with the garage sound at first. “I heard ‘Booo!’ and didn’t even think it was garage because Sticky’s production is more reggae and dancehall-influenced,” she says. Artists like Lauryn Hill, Foxy Brown and Tanya Stephens inspired Stush heavily, especially the latter. “The way Tanya would put things together without being slack got me straight away. I thought: ‘I can do this thing without having to say slack lyrics.’”

Sticky invited Stush down to the “Booo!” video shoot. The duo then teamed up for “Dollar Sign” in 2002. Stush, by now, was obsessed with Capleton’s More Fire album. “I always had it in my head that UK garage was dancehall sped-up so that’s how I attacked it,” she says.

“Dark garage” classics like More Fire Crew’s “Oi”, Pay As U Go’s “Know We”, K2 Family’s “Bouncing Flow”, Heartless Crew’s “Heartless Theme”, So Solid Crew’s “They Don’t Know/Envy”, Maxwell D’s “Serious” and Tubby T’s “Tales Of The Hood” are the strongest examples of dancehall-infused UKG, which acted as a precursor to grime.

The Caribbean influence is still a cornerstone in black British music today, and can be seen in everything from Giggs’ dancehall-derived flow and Russ’ Elephant Man-inspired dance tunes, to the foundations of Afroswing and, of course, grime. The rowdy cousin of UKG is dancehall’s kin. A grime set in 2019 mirrors a Saxon Sound dance 30-plus years ago—emcees wanting to spit their cruddiest 8-bar for a reload. And clashing still feeds the culture. The genre’s founding fathers—Wiley, Jammer, Footsie—are sons of men who played reggae in a sound-system or band. Maxwell D, a pivotal emcee in UK garage and grime, also fits the bill: he’s the son of Natty B, the reggae countdown presenter on the now-defunct black radio station Choice FM.

“Grime had a big dancehall element because a lot of the people making it—Wiley, myself and others—we’re from a dancehall background,” says Maxwell D. “Our parents are Jamaican, too.” Grime sprayers such as Armour, God’s Gift, Jamakabi, Flowdan, Riko Dan and Shizzle also drew countless reloads with their yardie-style flows. Ultimately, this scene is a product of everything that came before it and manages to hold onto long-lost values of Jamaican soundsystem culture (Wiley’s single “Boasty”, with Stefflon Don, Sean Paul and Idris Elba, is arguably the biggest dancehall song globally right now).

About time, too.

71 years on from Windrush, the British government finally thought that its contributions were worth acknowledging. The more appropriate would have been the 70th year, which we saw was marred by the Windrush Scandal. So now they want to celebrate? The cynic in me—a Windrush Generation grandchild—finds it a bit coincidental. Why did it take 71 years? To a post-war Britain, Caribbean migrants brought over culture that impacted the way Brits talk, eat and rave, amongst countless other things. What did we get in return? Persecution. Discrimination. Deportation.

Today and forever, we say thank you: Thank you to the Windrush Generation for injecting colour and flavour into Britain and changing our lives for the better.