On June 28, 1997, Mike Tyson chewed off a chunk of Evander Holyfield’s ear. Twenty years later, boxing is still bleeding from the wound.

The spectacle of one boxer biting off a body part of another in the name of sport was unheard-of even in the often brutal world of the prize ring.

Boxing has had its share of great fighters doing inexplicable, self-destructive things in the heat of battle. Jack Dempsey stood over Gene Tunney in their 1927 rematch, possibly costing himself a chance to regain the title in the famous Battle of the Long Count. Roberto Duran impulsively quit on Sugar Ray Leonard in the eighth round of their 1980 rematch, introducing the words “No mas’’ into the sports lexicon.

But never has a fighter done what Mike Tyson did that night.

All professional sports have had their moments of infamously unsportsmanlike behavior—Juan Marichal hitting John Roseboro over the head with a baseball bat in 1965, Kermit Washington levelling Rudy Tomjanovich with a sucker punch in 1977, Pete Rose steamrolling Ray Fosse in the 1970 All-Star Game (for Christ’s sake!). But the deliberate biting of an opponent’s ear, and not just biting it, but tearing through the flesh and cartilage and ripping it away from the skull, the way a rabid animal would flay the meat off a carcass, was unimaginable even in the world of professional prizefighting.

At the time, it was taken for granted that the career of Mike Tyson, which had begun in such promise 15 years earlier, had now ended in disgrace. And for many, it appeared the same fate would befall boxing.

“It was horrific,’’ says promoter Bob Arum.

“Human beings don’t do things like that,’’ says former HBO vice-president Ross Greenburg.

“I wondered if we were watching the end of boxing as we know it,’’ says Mike Weisman, the producer of NBC Sports fight telecasts for nearly 20 years.

“I still can’t believe I bit his ear. What was I thinking?’’ Tyson wrote in the forward to “The Bite Fight,’’ George Willis’ 2013 book about that unforgettable night.

And in fact, that fight—considering the shock of their first meeting, the viciousness of the pre-fight buildup, and the amount of worldwide attention focused on this event and those two athletes—might very well have dealt a KO blow to a sport that has seemingly been dying a slow death for the past 40 years.

If not, of course, for the grace and courage of Holyfield: “I think what I did that night saved the game of boxing.”

The fight lasted eight minutes and 21 seconds, but its repercussions are still felt two decades later. And as he often is, Holyfield was absolutely right.

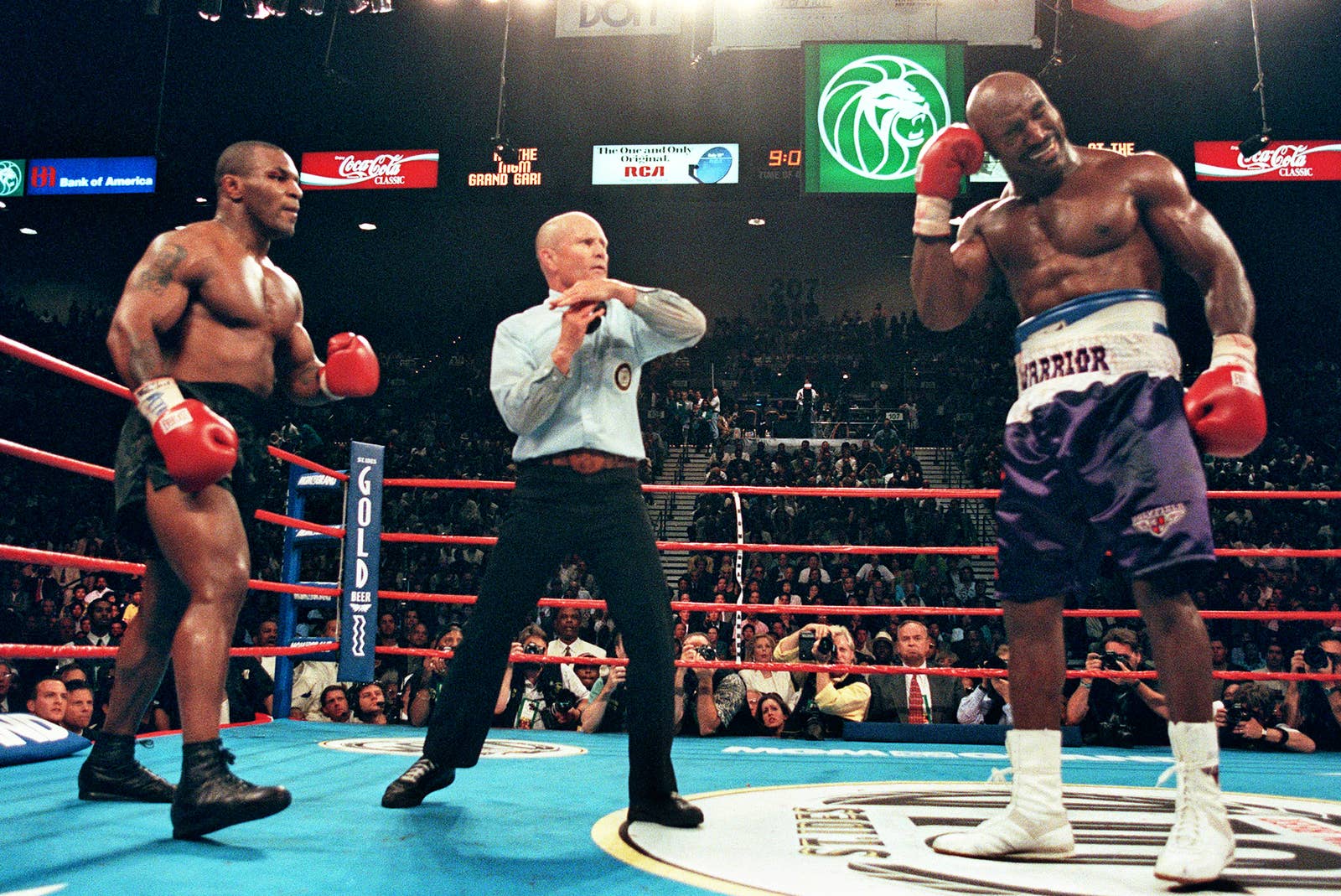

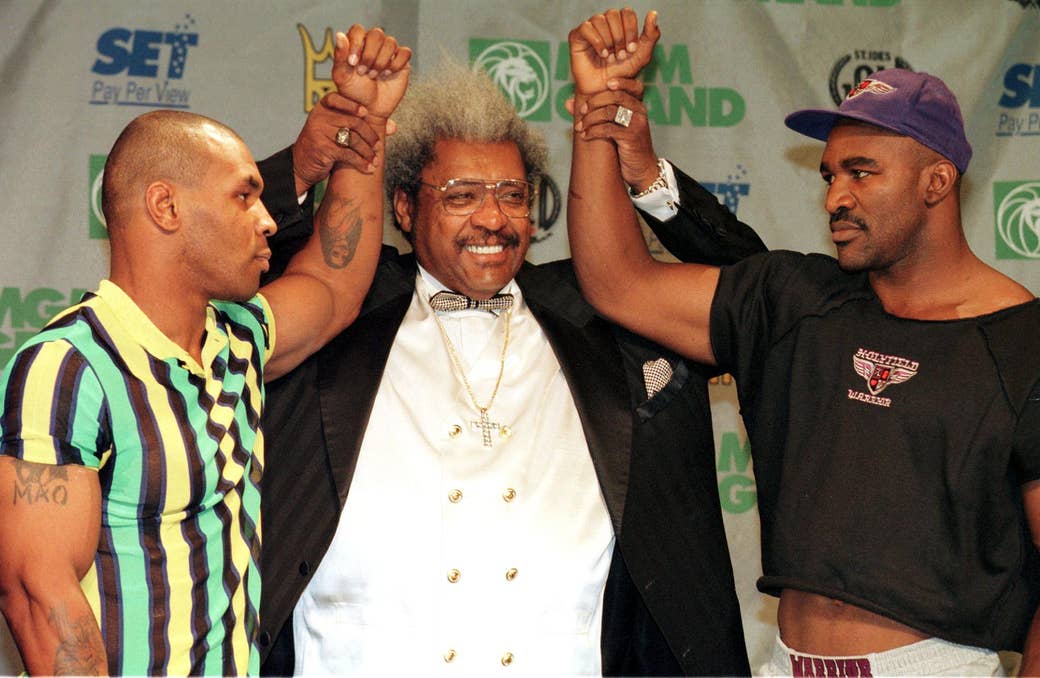

Tyson and Holyfield fought twice in the space of seven months. The first fight, on November 9, 1996, was a fairly conventional beatdown. The rematch, on June 28, 1997, had all the brutality of the first fight, with an additional element: A touch of cannibalism.

But a fight between Tyson and Holyfield had been in the works for more than a decade, since the two sparred as amateurs before the 1984 Olympics. But they managed to avoid one another as pros for more than seven years. Tyson and Holyfield were originally scheduled to fight on Nov. 8, 1991. Holyfield had knocked out Buster Douglas, the surprise conqueror of Tyson, the year before and held the WBA and IBF heavyweight titles. Tyson was an ex-champion, but at just 25 years old, it was considered only a matter of time before he would regain his rightful place atop the heavyweight division.

Tyson pulled out with an injury, and three months later, on March 26, 1992, was convicted of the rape of a beauty pageant contestant. The fight would be put on hold for nearly five years. When the fight finally took place, Tyson—despite having beaten four non-threatening opponents in unremarkable performances since his release—was installed as a 25-1 favorite, mainly on reputation and the fact that Holyfield seemed to be on the decline. He had lost his titles to Michael Moorer and two of three fights to Riddick Bowe, and had struggled to defeat Bobby Czyz, an overstuffed middleweight.

It was expected to be a mismatch. And it was, just not how most expected. Holyfield manhandled Tyson from the opening round, dropped him with a body shot in the sixth, and pummeled him into submission in the 11th round. After the bout, Tyson, meek as a puppy, virtually crawled to Holyfield at the post-fight news conference, whimpering, “I just want to touch your hand, man.’’

“The fact is, Mike never did want to fight me,’’ says Holyfield. “Ever since we sparred when Mike was 17 and I was 21. I used to tell him, ‘You’re a kid. I’m a grown man. You can’t do nothing to me.’ Mike knew that I was strong and I wasn’t scared of nobody.’’

Holyfield said he suspected Tyson would resort to illegal tactics in the rematch, based on the prediction of a man he calls “The Prophet,’’ a minister at a Las Vegas church the religious Holyfield regularly attended when training for a fight.

“The Prophet told me [Tyson] was going to do something terrible, but I never thought it would be biting,’’ Holyfield said. “You know, Tyson was always trying to break your arm, head-butt you, throw elbows—he did all that stuff. But [the Prophet] told me, he’s going to try to hurt you in the face area. And I said, ‘That’s what usually happens in boxing—you get hit in the face.’ I never thought about my ear.’’

A prophet of another sort, Teddy Atlas, the boxing trainer who had trained the teenaged Tyson at Cus D’Amato’s camp up in Catskill, N.Y., also predicted Tyson would foul Holyfield. “He won’t accept getting beat up again,’’ Atlas said. “He’ll do something to get out of the fight.’’

It turned out that Tyson’s groveling to Holyfield after the first fight was just an act. Tyson was enraged by what he thought were Holyfield’s deliberate head butts in the bout, and Tyson’s camp, convinced that Holyfield was on steroids, had forced him to take a test before the first fight. Holyfield agreed, on the condition that the results not be released until after the fight was over. It was a strategy, Holyfield says, designed to keep the Tyson camp guessing and on edge.

After the fight, when the results came back negative, Tyson was further enraged. “They were very disappointed,’’ Holyfield said. “That took away all their excuses.’’

Plus, Tyson’s camp placed some of the blame for Holyfield’s butting on Mitch Halper, who refereed the first fight. They insisted Halpern be replaced, and the 30-year-old referee voluntarily stepped aside, to be replaced by Mills Lane. The referee switch would turn out to have a profound effect on the outcome of the bout.

The opening rounds of Tyson-Holyfield II were a replay of the first fight, only even more one-sided for Holyfield. “I could tell I had him, because he was just trying to outbox me,’’ says Holyfield. “He always wants to make you go back, but in this one, he wasn’t aggressive. He came to a line and he wouldn’t go no further. I kinda felt that he didn’t want to take the chance of stepping in. It was like he realized, ‘Oh, shoot, I’m in trouble.’’’

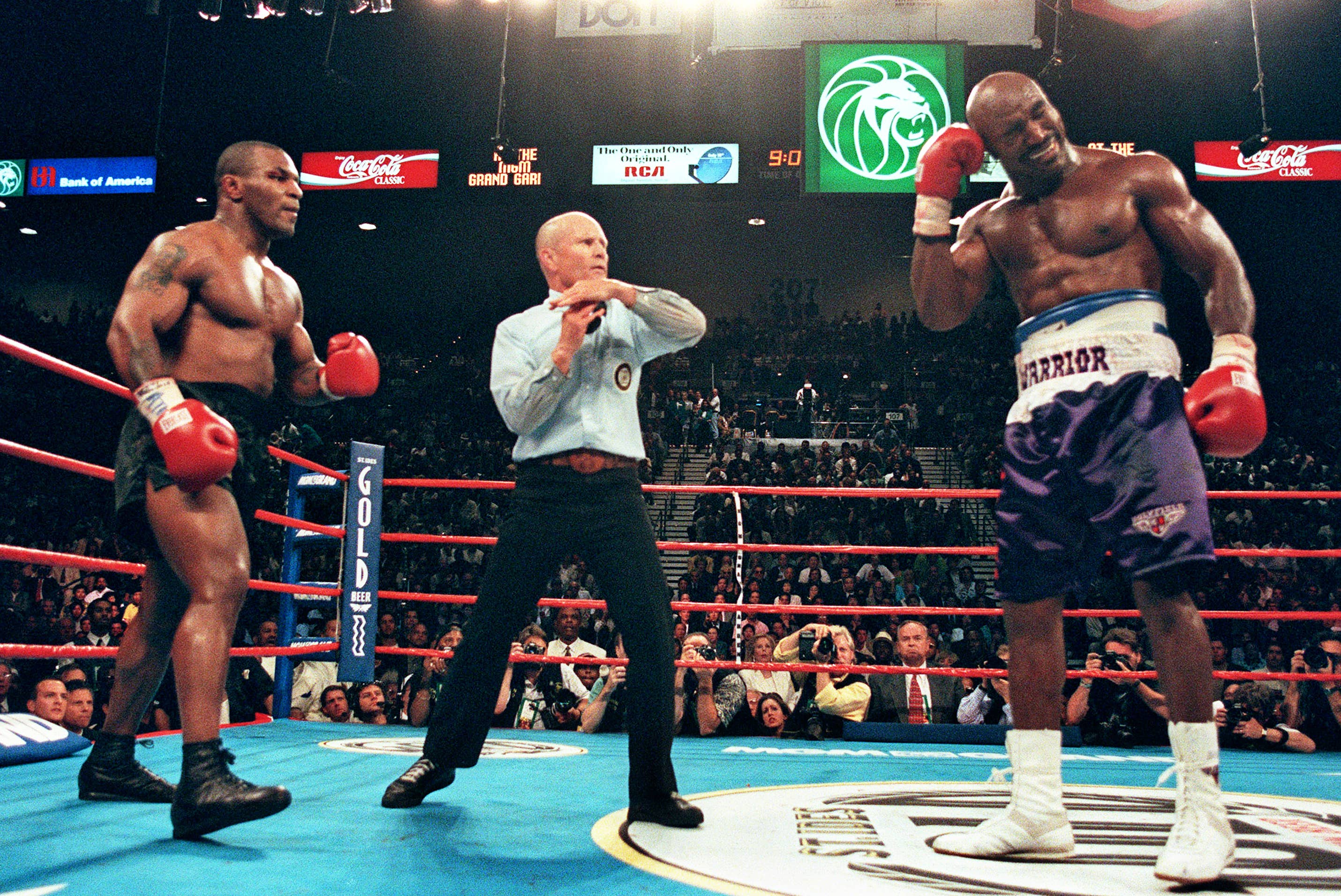

But Tyson came on in the third round and landed several hard shots. When they didn’t have the intended effect on Holyfield, the fight took its final ugly turn. With 33 seconds left in the round, the two fighters’ heads came together.

“We were on the inside and I went to put my head in to bridge him and use my neck muscles,’’ says Holyfield. “I was relaxed and all of a sudden he bit me.’’

That is putting it mildly. What Tyson did was dig his front teeth into the top of Holyfield’s left ear, and with a rapid, back and forth twisting motion of his head, tear off a thumbnail-sized chunk of flesh and cartilage. Then he spat it onto the canvas in a grotesque and savage show of defiance.

“I don’t remember much because I was too enraged,’’ Tyson wrote in his autobiography, “Undisputed Truth.’’ “I must have spit his earlobe on the canvas because I was pointing at it. It was like, ‘There, you take that!’’’

Although it wasn’t immediately clear even to ringsiders what had happened, since the fighters were fighting in close, when they separated it was clear something out of the ordinary had occurred. Holyfield pressed a glove to his mangled left ear and began jumping up and down, in obvious pain.

“It was just like when somebody takes a pin and sticks you in the butt,’’ says Holyfield. “It’s just a shock. All I know is, it hurt, and the first thing that popped into my head was to bite him back. When you grow up in the ghetto and somebody do something to you, the first thing you think of is do it to him worse.’’

Inches away from the fighters, referee Mills Lane was not sure what he had just witnessed. Neither was Marc Ratner, the executive director of the Nevada State Athletic Commission, sitting at the ring apron, nor judge Duane Ford next to him. Surrounded by TV monitors in the Showtime truck, director Bob Dunphy and producer David Dinkins Jr. could not believe what they thought they had just seen.

“With the benefit of the multiple angles, there’s very little that can happen in there that you don’t notice,’’ says Dinkins. “There was actually a moment when people thought maybe Holyfield had stopped, that he had retired from the fight.’’

“The impact and clarity of it wasn’t immediately clear until you saw the back of Holyfield and this blood streaming down the back of his head,’’ says Dunphy. “There was almost silence in the truck because it was an absolute shock.’’

The action stopped as Lane conferred first with Ratner and then with ringside physician Flip Homansky. Lane’s first reaction was to tell Ratner that he was going to disqualify Tyson.

"the first thing that popped into my head was to bite him back. When you grow up in the ghetto and somebody do something to you, the first thing you think of is do IT TO HIM WORSE."

“You sure you want to do that?,’’ Ratner asked his referee.

“I’ve been a football and basketball referee for 25 years and one of the first things we’ve always been taught is when an official tells you a player has been ejected or disqualified, you always ask is, “Are you sure?’’ Because you want the official to think about what he said. You don’t want him to make an emotional decision.’’

Instead, Lane called over Homansky to take a look at Holyfield’s injury. Homansky said the fight could continue.

A full two minutes and 20 seconds, during which Holyfield’s trainer, Don Turner, squirted water onto Holyfield’s wound and Holyfield demanded his mouthpiece —“So I could go and knock him out,’’ says Holyfield—elapsed before Lane ordered the action to resume.

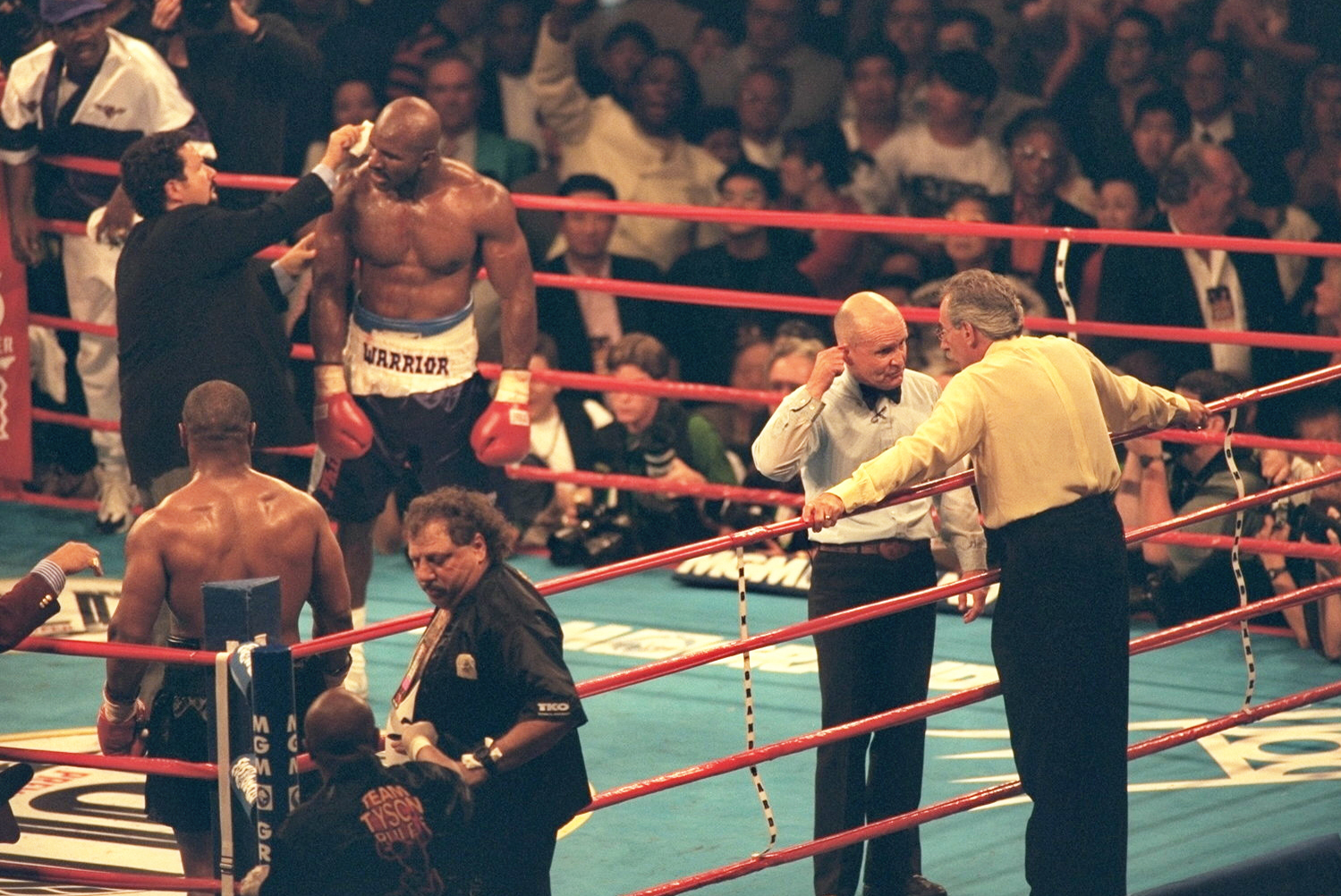

A mere 15 seconds later, Tyson did it again. Not as deeply, but with the same level of bad intentions. Holyfield hopped up and down again, this time more in rage than in pain, but Lane allowed the round to continue to the bell.

“I’m sitting there thinking, OK, again? Again?,’’ says Dinkins. “Tyson went back for another taste? I actually think the second time was more shocking than the first time. What was he thinking? Had he just lost his mind?’’

What he had lost was the fight—and $3 million, after the commission fined Tyson 10% of his $30 million purse July 9. This time, Ratner did not try to talk Lane out of disqualifying Tyson, which he did between rounds, ending the most lucrative prizefight in history in a swirl of confusion and violence. Members of both camps stormed the ring. Fights broke out in the crowd. Tyson, enraged and still gloved, swung at anything within arm’s length.

And sitting two seats away from Holyfield’s corner, Mitch Libonati, a member of the MGM Grand’s boxing staff whose job it was to maintain the ring between bouts—a responsibility that included wiping up excess water, blood, and in this night, flesh, from the canvas—knew immediately what he had to do.

“I knew that dude, not only spit out the mouthpiece but he spit something else out,’’ says Libonati. “I knew it was there. And then we had the chaos and all the people fighting in the ring and I remember thinking, that thing ain’t going to be there. It’s gone. But once I got into the ring after the melee, I was like, ‘Holy crap, it’s right there!’’ It was right below my feet.’’

Libonati picked up the hunk of flesh and wrapped it in a latex glove, put the glove in an ice bucket and brought it to Holyfield’s dressing room.

“It wasn’t a big deal. I was just being a good employee,’’ he says. “In my mind, I was thinking, the dude needs this. It was just a matter of doing the right thing.’’

Watching the fight at a friends’ pool party, Dr. Julio Garcia had a feeling he would have to go to work that night. A plastic surgeon, he had sewn up many a Vegas boxer and he knew Holyfield was going to need a few stitches. When his beeper rang, he knew who it was before he returned the call.

“The left ear had a chunk of skin missing and the cartilage was exposed,’’ says Garcia. “I had the small piece of skin in the bucket, but when I went to change into my scrubs and came back, it had vanished. Just disappeared. I never did find out what happened to it. So I just took a little flap of skin from the back of his ear and folded it over to close the wound.’’

Garcia says a re-attachment probably would not have been possible, anyway.

“The bite went through and through, and when it ripped off his ear, the skin that encased the cartilage totally separated from the cartilage,’’ he says. “It was like they had peeled a banana. And without that piece of cartilage, there really wasn’t much I could do.’’

Later that night, after Holyfield had left, a hotel employee called to say they had found the bit of cartilage—but it had been trampled in the post-fight melee and was unusable. “I told them to do what they wanted with it,’’ says Garcia.

For years, Garcia displayed a photo on the wall of his office of Holyfield’s bloodied left ear. That is, until the day Tyson was brought to his office to have a cut stitched up.

“When I heard he was coming in, I quickly took that picture down,’’ he says. “I didn’t want to have any problems.’’

Dr. Garcia’s role in the Ear Bite Fight would land him appearances on the Larry King Show and other talk shows, but the honor he is most proud of? “I made it into the 1990s edition of Trivial Pursuit,’’ he says.

After granting an interview to Showtime’s Jim Gray in which he contended the bite was mere retaliation for Holyfield’s deliberate butting, Tyson wept in his dressing room. “It’s over, it’s over. I know my career is over,’’ he repeated, again and again.

Tyson would fight again—10 more times, in fact—but he never won another major fight and was stopped in three of his last four fights, quitting on one knee in his final bout against journeyman Kevin McBride on June 11, 2005.

Holyfield fought 20 more times, losing his titles to Lennox Lewis in 1999 but regaining a version of the title a year later. He finally retired, at 48, on a win over Brian Nielsen on May 7, 2011. Earlier this month, he was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota, New York.

And although Tyson has never apologized—“His apology was to say, ‘Hey, we cool, man?,’’ says Holyfield—as a man of faith, Holyfield has found it within himself to forgive Tyson.

“I got over it, I forgave him, and kinda look at it on the spiritual side to show people that life is about forgiving,’’ he says. “The Bible says everybody got a bad spot. And one of the biggest reasons why it was easy for me to forgive him is because I used to bite my brothers all the time. They were older and bigger than me and when they would put me in a headlock I would bite them to get out.’’

"one of the biggest reasons why it was easy for me to forgive him is because I used to bite my brothers all the time."

In Holyfield’s mind, Tyson was just biting an older brother he couldn’t beat any other way.

The damage to boxing, however, did not heal as easily. The images of the sport’s biggest star in decades—already tarnished by the rape conviction, his public divorce from Robin Givens with allegations of domestic abuse, and all-around anti-social behavior—was irreparably damaged. And boxing, riding high for the nearly 11-year period between Nov. 22, 1986, when Tyson knocked out Trevor Berbick to become the youngest heavyweight champion in history, and June 28, 1997, when he became one of its most infamous scoundrels, slipped back into the downward spiral it had been in since the mid-1970s.

The jury remains out, however, on whether the Bite Fight was the catalyst of its decline, or merely the final blow.

“It was devastating to the sport. The repercussions were miserable. We were done. He definitely scarred the sport,’’ says Greenburg, who produced all of Tyson’s title fights for HBO before he went to jail.

”That was a time, even as a fan of boxing, when it was hard to defend,’’ Weisman says, who produced NBC’s fights from 1973 to 1990. “I used to get frustrated by the fact that any time we did boxing at NBC, we had higher ratings than any of our other shows, but the advertising department always said, we can’t sell it. Advertisers didn’t want to be attached to it because of the violent nature of it. And frankly, at that point, even I thought the sport needed to make some major changes.’’

“It’s hard enough, even in the good times, to get commercial support for boxing,’’ says Seth Abraham, who signed Tyson to a multi-million dollar contract as president of HBO in the 1980s. “When you have this kind of roguish, thuggish behavior, it becomes a cancer. I would say that 75% of the companies in this country won’t go near boxing.’’

Still, Abraham said, “That fight did not finish boxing. But it was the exclamation point.’’

“Boxing is resilient,’’ says Duane Ford. “I don’t think it’s ever going to kill itself. If it was going to bleed to death it would have done it by now. It certainly has cut enough of its own arteries.’’

Others, however, see the fight as not so much a boxing problem, but as a Tyson problem.

“It had no effect because it was Tyson, and Tyson was always considered a renegade,’’ said Arum, who promoted many of Tyson’s early fights on ESPN’s Top Rank Boxing series. “It wasn’t like a black mark on boxing, like a terrible officiating job or a bad decision. It was all blamed on Tyson. People realized this is not representative of how boxers behave, even occasionally.’’

“Face it, we like crazy shit as a society,’’ says boxing promoter Lou DiBella, an HBO vice-president during Tyson’s heyday. “That was such a fucking wild event, and there was so much written and said about it afterward, that I don’t think people were running around feeling cheated. They were more like, can you believe this? It was the talk at every water cooler in the country. And by the way, I’m sure there were a lot of people who said, ‘Holy shit, Mike Tyson bit his ear off!’”

Another promoter, who requested anonymity, saw the Ear Bite Fight as the forerunner of today’s mixed martial arts matches, with their cartoonish violence.

“People like brutality,’’ says the promoter. “What the fuck do you think the appeal of MMA is? You’re watching a guy bleeding profusely, prone against the floor and another guy kneeing him in the face. And it’s more popular than boxing now. It’s the same argument why a live execution would do a great buy rate.’’

A couple of days after the bout, a lawyer came into Marc Ratner’s office claiming he would file a class action suit against the Nevada State Athletic Commission on the grounds that fight fans had not gotten what they paid for.

“And I just smiled and said, I think it was the best TV show anyone ever paid for,’’ says Ratner. “The suit was never filed.’’

Holyfield, in fact, saw the ending of the Bite Fight not as a stain on the sport, but as one of its rare shining moments.

“I think one of the biggest things it showed was that boxing is controlled,’’ he says. “If both of us had behaved like that I think boxing would have been extinct forever. That’s why I think what I did that night saved the sport. Because if I would have bit him back like I wanted to, boxing would have been over. They would have said, ‘These are the two best people in the game and look what happened. Ladies and gentlemen, that’s it. Turn off the lights.’’’

Twenty years later, boxing’s light is dimmer, though it continues to glow.

The heavyweight division has never been the same, and although Tyson has undergone something of an image makeover following the writing of his autobiography, upon which he based the Spike Lee-produced one-man show he has performed on Broadway and in Vegas, and kiddie fare such as “The Mike Tyson Mysteries,’’ what he did in the ring that night is sure to be recounted in the first line of his obituary, the way the words “no mas’’ will someday appear high in Roberto Duran’s.

And the biggest, most lucrative fight anyone can imagine these days matches Floyd Mayweather—a 40-year-old boxer who has not fought in two years and whose appeal, like Tyson’s, is that of an anti-hero—and Conor McGregor, a mixed-martial artist who has never had a professional boxing match.

Those two might very well divide a pot of more than $200 million.

And if one decides to bite off the other’s ear? The act of barbarism that repulsed millions in 1997 might be sufficient grounds for a rematch.