This feature was originally published on October 25, 2017.

History got all fucked up when everyone thought that the Baby Boomers had the most important story to tell. And of course the white male baby boomers had the loudest voices. So here we are, in 2017, still feeling the cultural and artistic reverberations from events that happened long after the '60s became American culture's supposed pivotal moment.

But the fact is that it wasn't the late '60s when everything changed—at least not in popular music. White people were listening to white people performing older black music at Woodstock (not to slight Jimi). And we grew up being told one thing, but knowing something else was true. American popular music today owes everything not to The Beatles or The Rolling Stones, but to the sparks of the late 1970s that took full flight in the '80s. To techno, to house music, to disco, to dancehall—and to hip-hop.

The '80s was hip-hop's first real decade, the era when everything started to blow up. There's an old saying that no idea's original: "There's nothing new under the sun. It's never what you do, but how it's done." And it's true that hip-hop was a continuation of a much longer story about black American culture. Hip-hop was about poor kids taking broken pieces of the world around them and putting them back together. This was the true break with history—the end of the beginning, if not the beginning of the end.

As complicated as it was creative, as contradictory as it was all-conquering, the story of hip-hop's eventual aesthetic takeover starts in the '80s. From artists like Slick Rick to the Fresh Prince, Public Enemy to the 2Live Crew, N.W.A to BDP, Salt-N-Pepa to Queen Latifah, The Fat Boys to De La Soul—this is where rap's various ideologies and innovations begin spinning outwards, spreading geographically and, culturally. Early on, it wasn't an album genre; hip-hop was all about parties and park jams, preserved and propagated via bootleg cassette. Soon after it was about stars and singles, disco loops and breakbeats, drum machines, and ultimately, albums. The art of the hip-hop album was perfected by the close of this remarkable decade. All these years later some discs sound dated while others feel fresher than ever. Which records have stood the test of time? Which one embodies hip-hop best? See if you can guess—or just start clicking. These are our picks for the Best Rap Albums of the 80s.

50. Run-D.M.C., King of Rock (1985)

Label: Profile/Arista

Less than a year after "Rock Box" became a landmark in the annals of hard rock guitar jams, Run-D.M.C. were, somewhat justifiably, convinced that they'd already conquered rap music, and prepared to claim the crown for rock as well. Their dalliance with Aerosmith was still to come, and in the meantime Jam Master Jay and co-producer Larry Smith cooked up genre-benders like "King Of Rock" and "Roots, Rap, Reggae" with guitarist Eddie Martinez laying down screaming riffs.

The album is dragged down by two long roasting sessions, "You Talk Too Much" and "It's Not Funny," in which Darryl McDaniels and the future Rev Run unload a gang of now-stale jokes. Nonetheless the inventive production and righteous rhymes of deep cuts like "Jam-Master Jammin'" and "Darryl And Joe (Krush-Groove 3)" make this album an essential. —Al Shipley

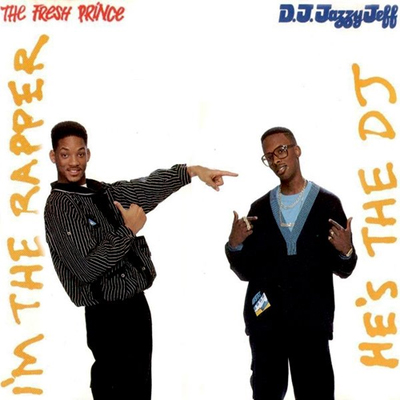

49. DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince, He's The DJ, I'm The Rapper (1988)

Label: Jive/RCA

It was the archetypical pop rap crossover moment—the goofy, kid-friendly single "Parents Just Don't Understand" won the first rap Grammy, and the album gave future multimedia superstar Will Smith his first platinum plaque. But it's also a clever, consistently enjoyable rap album, with 1988's ubiquitous James Brown breaks on the slamming "Brand New Funk," and playfully conceptual tracks buoyed by the Fresh Prince's sly one-liners and smooth delivery, plainly influenced by Slick Rick (whose voice is sampled on "As We Go"). And even if it was already clear which member of the duo was a charismatic superstar in the making, they DJ kept equal billing, as Jazzy Jeff got multiple tracks to show off his innovative scratching and techniques. —Al Shipley

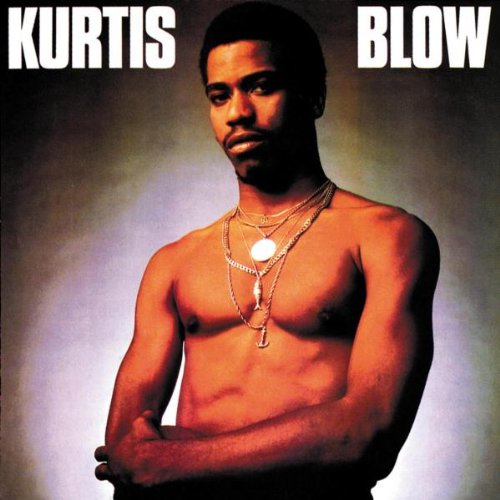

48. Kurtis Blow, Kurtis Blow (1984)

Label: Mercury/PolyGram Records

In 1980 Kurtis Blow became the first rapper to prove that a career in rap was even possible. Blessed with a booming, elastic, singsong voice, he became the first MC to sign with a major label in 1979—hot on the heels of the "Rappers Delight" phenomenon—and dropped the hit single "Christmas Rappin'."

He came right back with a self-titled debut album the following year, a seven-cut collection powered by "The Breaks," which became the first gold single in rap history. Blow's exuberant flow on the cut still thrills three decades later. He would continue to be a force in hip-hop, touring the world, producing, and acting, but that first album remains the high point of his recording career. —Rob Kenner

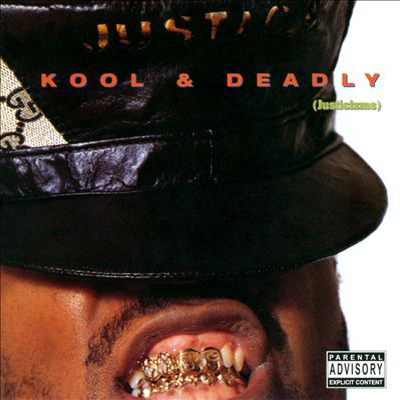

47. Just Ice, Kool & Deadly (1987)

Label: Fresh/Sleeping Bag Records

When the musclebound Brooklyn rudeboy Just-Ice tapped KRS-One from the Boogie Down Bronx to produce his sophomore album, the result was bound to be rough, rugged, and raw. The album cover—zooming in on Just's gold-plated grill—left no doubt that this album was every bit as deadly as the title suggested.

It was also a historic fusion of dancehall and hip-hop, pointing the way forward to the likes of Super Cat and Biggie, Brand Nubian, and The Fugees. On "Goin' Way Back," Jus pays homage to hip-hop's founding fathers, but the crown jewel in this hard-body album is the raggamufin dancehall track "Moshitup" on which KRS and Jus body all dibby dibby soundbwoys in the area. —Rob Kenner

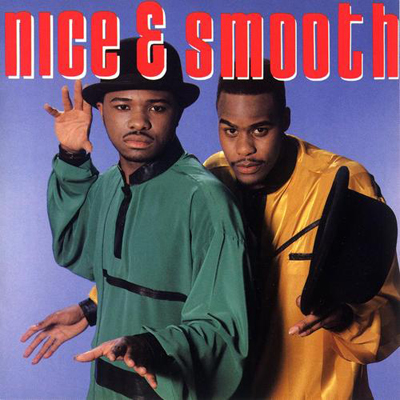

46. Nice & Smooth, Nice & Smooth (1989)

Label: Fresh/Sleeping Bag Records, Priority/EMI Records

Perhaps best known for their guest appearance on Gangstarr's 1992 B-side classic "DWYCK," Greg Nice and Smooth B first made their mark in 1989 with this self-titled album on Fresh/Sleeping Bag. The pair's odd-couple chemistry hinged on the contrast between Smooth B's laid-back loverman style and Greg N-I-C-E manic humor. With DJ Teddy Ted on the wheels of steel, they rhymed over everything from classic R&B breaks (Mary Jane Girls "All NIght Long" is sampled on "More & More Hits") and reggae hooks (Yellowman's "Zunguzunguzeng" appears on "Dope On a Rope"). Although their biggest hit, "Sometimes I Rhyme Slow," would come on their sophomore album, their debut disc set the template for one of hip-hop's greatest duos. —Rob Kenner

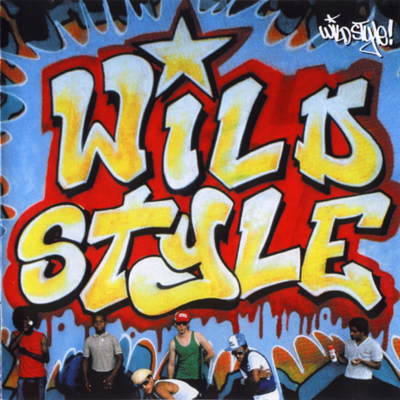

45. Various Artists, Wild Style Soundtrack (1983)

Label: Animal

Though loosely scripted and staged (and not a documentary) Wild Style broke barriers as the first theatrical feature film about hip-hop culture. And its greatest asset was the use of real life performers and musicians, essentially playing themselves throughout the film.

On the soundtrack album, crews like the Cold Crush Brothers and the Fantastic Freaks no longer have to take a backseat to an ambling plot about a graffiti writer named Zoro and simply shine doing what they do best, often on the stage of The Dixie or The Amphitheatre. But what really makes the soundtrack a fascinating artifact is more casual interludes like Busy Bee freestyling in the back of a limo, Double Trouble running through a routine on a stoop, and Fab 5 Freddy's spacey instrumental "Cuckoo Clocking." —Al Shipley

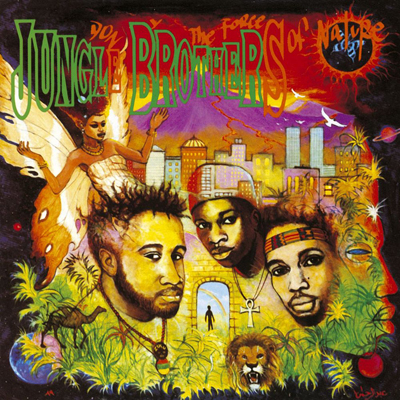

44. Jungle Brothers, Done By the Forces of Nature (1989)

Label: Warner Bros.

It's not on the level of De La Soul Is Dead, or The Low End Theory, but in a certain light, the Jungle Brothers' second album, Done By the Forces of Nature, stands as the definitive album to come out of the New York's beloved Native Tongues collective. If the ethos of the Native Tongues movement could be distilled into one essential idea, it might be something along the lines of: Through music, we can connect to our roots and access something pure and good and true and natural that's too often hidden behind the plastic façade of the modern American urban living.

Afrocentic, slightly mystic, and resolutely positive, the Jungle Brothers—Sammy B, Mike and Afrika Baby Bam—put their pastoral poetry over the big drums of rap's urban soundscape and came up with something new and strong and beautiful. "Same old story/Over and over," Afrika rhymes on "Sunshine." "Someone trying to take knowledge over/So I fight back with a native dance/Sing my song and chant my chants..." —Dave Bry

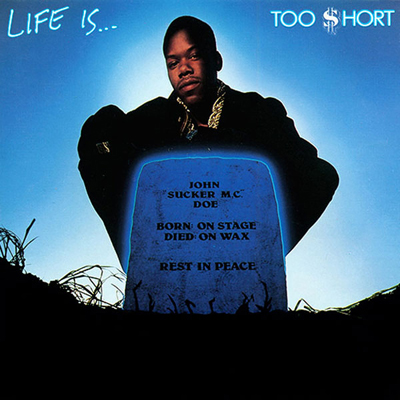

43. Too $hort, Life Is...Too Short (1988)

Label: Dangerous Music/Jive/RCA

Self-proclaimed coldness is one of the foundation identity tropes of rap music. It's there in the nicknames so many artists have chosen: Kool Herc, Kool Moe Dee, Kool G. Rap, Kool Keith, Fresh Kid Ice, Ice-T, Ice Cube, Vanilla Ice, Kid Frost, Chill Rob G, Cold 187um—the list goes on. But what is the definitive sound of coldness? What is the coldest sound rap music has ever produced?

I heard it for the first time in 1989. I can remember the moment precisely. A bunch of us were hanging out by the baseball field at my high-school, off to the side of the stands. There was a game going on but we were only half-watching. My friend Jason Appio came over wearing a walkman. Jason liked rap and he knew I liked rap, and he took off his headphones and handed them to me. "This is best shit out," he said, and as I put them on he showed me the cover to the cassette tape inside. It was a picture of dude with a fat gold chain and a smirk on his face, crouching behind a gravestone glowing electric blue. "John 'Sucker M.C.' Doe," it said on the gravestone. "Born on stage. Died on wax. Rest in peace."

I pressed play and heard a beat: a ticking cymbal that sounded like change clinking in a nervous hand. Then the low-end: giant TR-808 drumbeats, a slow, throbbing 16-note synth loop. Then the rhyme: steady, simple, measured, emotionless: "Then the new style came/The bass got deeper/You gave up the mic/And bought you a beeper/Do you wanna rap or sell coke?/Brothers like you ain't never broke..."

Too $hort, the rapper was called. Life Is... Too $hort was the album, his fifth release, it turned out, but the first to reach us in New Jersey all the way from his native Oakland. It was awesome. I was instantly transfixed. It sounded, frankly, like snorting cocaine felt. Listening to it put a chill in my veins. And in memory, it captures an essence of 1980's culture like nothing else.

Has any rap ever gotten any colder, when you really think about what the word means, what coldness would sound like, in terms of the synesthetic magic that music can create? I don't think so. I can't think of anything. I'm listening to the album now, as I type this. Makes those "Cold Challenge" commercial that Ice Cube does for Coors Light commercials seem like a lukewarm baby bath. —Dave Bry

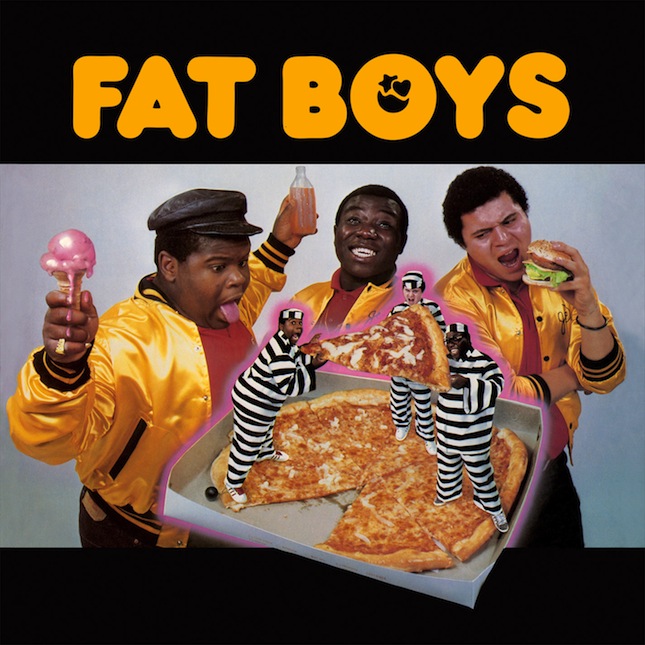

42. Fat Boys, Fat Boys (1984)

Label: Sutra

At first glance the Fat Boys might've looked like a novelty group. MCs Prince Markie Dee and Kool Rock-Ski and Buff Love, the self-professed Human Beat Box (R.I.P.), arrived on the scene fresh to death and big as polar bears, but despite their gleefully loutish demeanor and cartoonish snack food obsession, they proved themselves as a formidable rap trio with their self-titled Kurtis Blow produced debut.

The Fat Boys kept it light, coasting on Markie Dee and Rock-Ski's jovial snack raps and Buff Love's human percussion while Blow blessed the boys with sparse but hooky soundscapes on songs like singles "Can You Feel It?" and "Fat Boys." Sometimes he hung back to let Buff Love shine, though. "Stick 'Em" adorns Markie, Rock-Ski and Buff's beatbox celebration with little more than a few scratches, and when "Human Beat Box" awards Buff complete control, he takes the opportunity to let us know his beats are as tough as any drum machine's.

The Fat Boys was deceptively accomplished despite the gluttonous pizza-loving front it proffered for casual onlookers, and Buff Love, Kool Rock-Ski and Prince Markie Dee's unapologetic ownership of their overweight stature opened up a lane for portly rap luminaries like Chubb Rock, Heavy D, Biggie, and Action Bronson to get on years later. —Craig Jenkins

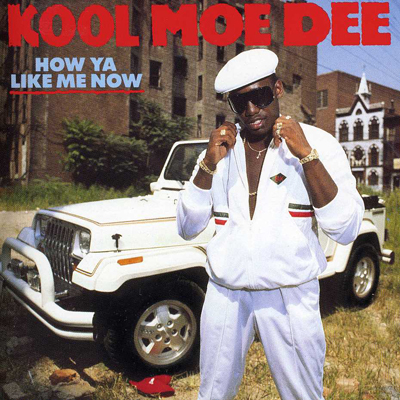

41. Kool Moe Dee, How Ya Like Me Now? (1987)

Label: Jive/RCA Records

When the early years of hip-hop are discussed, the Bronx gets all the love while the legends of Harlem are regulated to footnote status. Yet, without a doubt, those uptown streets also had their share of rappers who could put it down on the mic. In the mind of many, Kool Moe Dee was one of the kings of Harlem, a Sugar Hill wordsmith who could either be cold dissing battle rapper or a warm storyteller spinning tales of gold digging skeezers or the wild streets of uptown.

Formerly a member of the Enjoy/Sugar Hill trio the Treacherous Three, the sunglasses wearing Kool Moe Dee released his self-titled debut album, which contained the hit Teddy Riley produced single "Go See the Doctor," in 1986. The following year, having gotten into a beef with LL Cool J over alleged style theft, Kool Moe Dee came out swinging on the title track of How You Like Me Know.

Teaming-up once again with Harlem homeboy Riley, himself on the cusp of producer superstardom, Moe Dee went in on LL Cool J with the venom of a villain. Over a then-innovative James Brown sample, he tells the Kangol cap wearing rapper that, "Rap is an art and I'm a Picasso...I'm bigger and better, forget about deffer." Unfortunately, this was just the beginning of their infamous rap war, in which LL Cool J's response "Jack the Ripper" was the "Ether" of the era.

Elsewhere, there are some interesting choices, like the damn near cover version of Paul Simon's AM-radio classic "50 Ways to Leave Your Lover." Yet, writing about his birthright streets of Harlem with the precision of a keen social observer is where Moe Dee's strengths really laid as proven on the album's standout track was "Wild Wild West." With the passion of Negro Renaissance poet, Moe Dee described those mean streets from the duel perspective of a lover and a fighter.

Considering that in '87, those blocks he was rapping about were a cracked-out nightmare, "Wild Wild West" also served as the perfect protest song against the drug dealing wild cowboys who were destroying the community. As a rebel and rhyme animal representing. —Michael Gonzales

40. MC Shan, Down By Law (1987)

Label: Cold Chillin/Warner Bros. Records

When MC Shan and his cousin Marley Marl linked up for "The Bridge," a seemingly innocuous toast to their native Queensbridge projects, they ended up making history. "The Bridge" inadvertently ticked off an epic war of attrition when the Bronx's Boogie Down Productions, none too amused with Marley's Juice Crew after an argument with crew member Mister Magic, interpreted the song as a claim that Queens was the birthplace of hip-hop. The resultant Bridge Wars remain one of hip-hop's coldest diss wars, and Shan's debut album Down By Law is a searing document of the struggle.

"Kill That Noise (Boogie Down Dis)" was the gut check to BDP's "Bridge" response "South Bronx," and the dancehall joint "Another One to Get Jealous Of" was brimming with barely contained ire. Down By Law's KRS ridicule is thorough, but Shan still finds time throughout to show off his range as a writer. Story songs like "Jane, Stop This Crazy Thing" and "Project Ho" called out treacherous women even as "Left Me Lonely" pined for affection, and "MC Space" toys around with astrological bars and electro sounds.

Down By Law was Shan's first full length, but we shouldn't forget that it was Marley Marl's too. Marley blesses Shan's missives with a spate of productions replete with clattering, inventive drum sounds (Marley'd recently discovered drum sampling in a happy studio accident), punchy funk samples, and, for the lighter material on the album's more sedate back end, ear-catching melodies and moody atmosphere. Marley and Shan's mix of bravado, open lyrical warfare, and battle-ready beats has lived on through multiple generations of fearless troublemakers. —Craig Jenkins

39. Treacherous Three, Treacherous Three (1984)

Label: Sugar Hill, MCA

The Treacherous Three were somewhat late to the party when it came to hip-hop artists releasing albums. Sugar Hill released their full-length debut in 1984, but they’d been together since the ‘70s, and had been issuing singles since 1980, the year of the landmark “New Rap Language” (with former member Spoonie Gee) and “Body Rock.”

Nothing on The Treacherous Three left as big a mark as those songs, but the LP still displayed the enormous talent of Special K, LA Sunshine and especially Kool Moe Dee, who was just a couple years away from his breakout as a solo artist. Every track on the album is in the 6-7 minute range, and other than the cheeseball sung bridge on “Whip It,” the trio’s well rehearsed back-and-forth rhyme routines dominate the proceedings. —Al Shipley

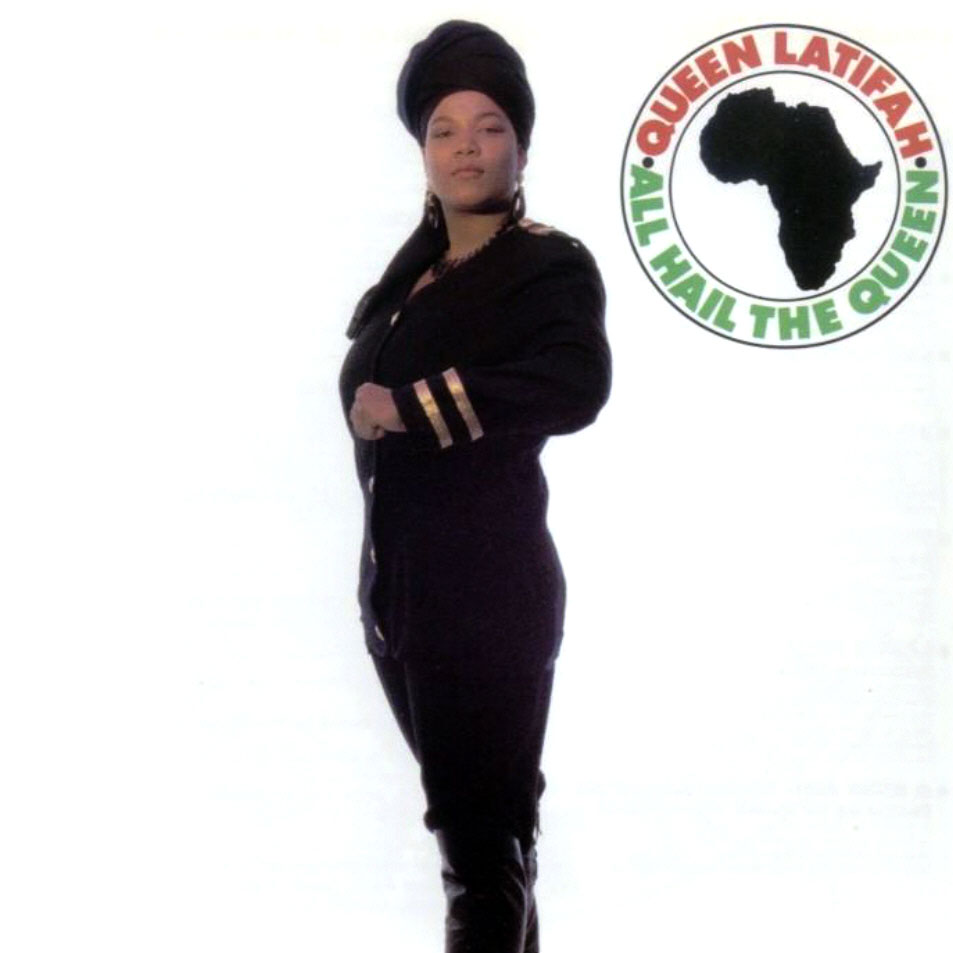

38. Queen Latifah, All Hail the Queen (1989)

Label: Tommy Boy

Though many now know Queen Latifah as an Academy Award nominated actress and talk show host, she spent the first decade of her career running with New York's Native Tongues collective and DJ Mark the 45 King's New Jersey Flavor Unit crew. Latifah's 1989 debut All Hail the Queen found the her dispensing darts about self-respect and Afrocentricity over beats by 45 King. Though All Hail the Queen was bolstered by 45 King's dance floor friendly hard funk boom bap and alley oops from guests like De La Soul and KRS-One, it's always very much Latifah's show.

"Evil That Men Do" addressed income-based inequality, while "Latifah's Law" and the Monie Love assisted hit single "Ladies First" challenged America's male power structure. Latifah was equally at home on lighter material too. She kills the party rocking opener "Dance for Me" and the hip-house excursion "Come into My House." Elsewhere "Princess of the Posse" and "The Pros" show off her singing skills and ease with reggae cadences. Her pen game's stellar throughout, leaving little question as to why she felt perfectly comfortable dressing like African royalty and holding court with A Tribe Called Quest and Naughty by Nature before discovering her silver screen calling. —Craig Jenkins

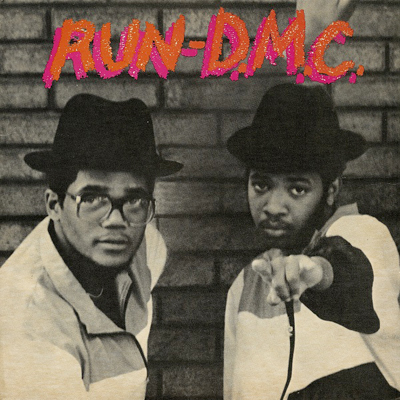

37. Run-D.M.C., Run-D.M.C. (1984)

Label: Profile, Arista

When Russell Simmons began making waves in hip-hop, first as a show promoter and then as a manager and producer, he brought his little brother Joseph along for the ride. The younger Simmons apprenticed under Kurtis Blow early on, but the day Joseph (Run) and his boy Darryl (D.M.C.) met DJ Jam Master Jay rocking crowds in a local park in Queens, hip-hop history was made.

Run-D.M.C. launched into a winning run of singles in 1983, from "It's Like That," born after the group convinced Russell and his producer friend Larry Smith to give them a shot at recording, to the inescapable, inimitable street anthem "Sucker MC's (Krush Groove 1)" and the seminal rap rock salvo "Rock Box." Smith had been working with electro/R&B pioneers Whodini at the time, and while Run-D.M.C. appreciated having a professional hand around as they were crafting their self-titled debut, they rejected the more melodic tendencies Smith brought to the proceedings in favor of stark, clattering noise.

The music was hard (The style of dress was hard too: peep the bucket hats and fedoras, dookie rope chains and black on black outfit architecture), but the lyrics were hard too. "It's Like That" is a fatalistic appraisal of inner city poverty in the style of "The Message." "Hard Times" followed suit, while "Sucker MC's" thumbed its nose at rivals.

There was a harshness to the lyricism, and Run and D.M.C.'s delivery brought a matching grit to the affair. Run-D.M.C. sounded as bleak and uncompromising as New York City looked at the time, and the record's massive, unrepentantly synthetic sound was instrumental in severing early rap's dependence on disco breaks from DJs' parents' record collections. It was one of the most singular and uniformly accomplished offerings by a hip-hop act up until that point, and this wasn't lost on listeners, whose patronage made it rap's first gold selling album. —Craig Jenkins

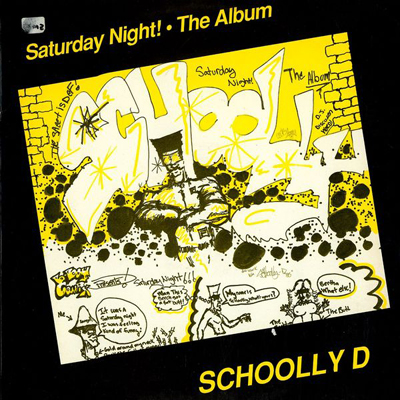

36. Schoolly D, Saturday Night! The Album (1987)

Label: Schoolly D

When people think of Philly rap music, they're more than likely to name check Will Smith or the Roots. Yet, for many old school rap fans who came of age in the 1980s, Schoolly D was the first city of brotherly love rapper that we heard. Releasing his chilling debut single "P.S.K. What Does It Mean" in 1985, a track whose title referred to the Philly gang Park Side Killers, the song has been baptized the first gangsta rap single. Influencing a generation of gun shooting, weed smoking, bitch slapping MCs to pick-up the mic, their might not be a Snoop if Schoolly hadn't led the way.

Two years later, Schoolly D., along with his dope DJ Code Money, released the stellar sophomore disc Saturday Night! The Album, for which he also drew the album cover and co-produced with Joe "The Butcher" Nicolo. Although not a wordsmith on the level of Rakim, Schoolly made songs that sounded great blaring in a club. In addition, as showcased throughout Saturday Night, the turntable acrobatics of DJ Code Money was serious as a heart attack. Just listen to the opening party joints "We Get Ill" and "Do It Do It" where Money sounds like a entire scratch orchestra, spinning crazily as a room full of grandmasters.

The stand-out track is "Saturday Night," a five-minute song where Schoolly details his bugged misadventures as he gets illy in Philly. Over hypnotic percussion and Cold Money's fly guy mixing, Schoolly tells his tale like a hip-hop Chester Himes. Blunted on reality as he tokes that "cheeba cheeba," Schoolly raps about his gun-toting mother, almost picking up a tranny, and wilding out with his Parkside posse. Hearing the genius in the gritty track, filmmaker Abel Ferrara used the song in his film, King of New York.

A decade before the Roots recorded their first album, MC Schoolly School was one of the best that Philadelphia had to offer. —Michael Gonzales

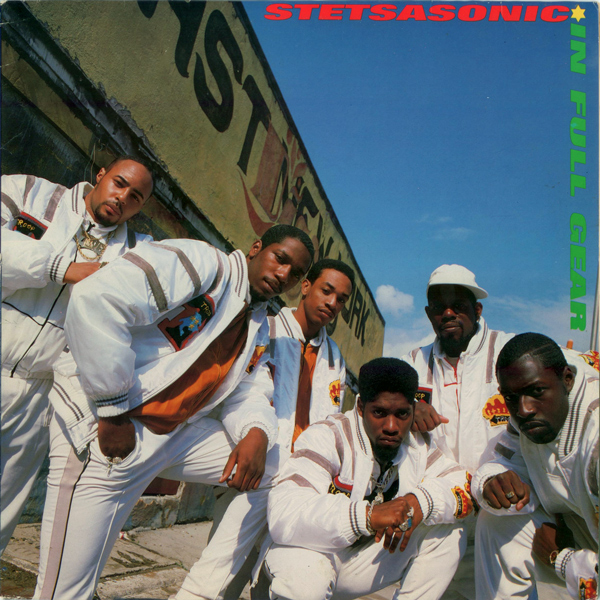

35. Stetsasonic, In Full Gear (1988)

Label: Tommy Boy

Although live instrumentation had its place in the disco breaks of early hip-hop, Stetsasonic stood out as the most prominent crew with a full service live band of the genre's first decade, long before ?uestlove and them got started. A year before Prince Paul would branch out into his groundbreaking production work for De La Soul, he was innovating with Stetsasonic on their sophomore album, combining the instrumentation with turntables and samplers in creative new ways.

"It's In My Song" features slamming live drums, while "Sally" still lights up old school mix show sets as one of the most enduring bangers of 1988. The group's most powerful mission statement came in the form of "Talkin' All That Jazz," a response to a jazz musician's gripes about sampling: "You criticize our method of how we make records/You said it wasn't art, so now we're gonna rip you apart." —Al Shipley

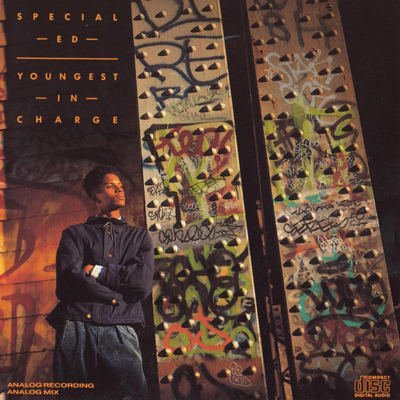

34. Special Ed, Youngest In Charge (1989)

Label: Profile/Arista/BMG

Soulja Boy wasn't the first teenage rapper. Back in the '80s, in fact, give or take a KRS One, most rappers were in their teens when their careers started to take off. But even at the time, Special Ed seemed a prodigy, a 16-year-old with a natural grasp of language. His comfortable, laid-back delivery balanced his expansive vocabulary with a veneer of casual-ness. But it wasn't something quite so simple as "complexity x coolness = $$$."

He was also a creative lyricist brimming with ideas. "Try to battle me and I'ma make it my job/To burn you as I turn you like a shish-ka-bob." The opening 1-2-3 punch of "Taxing" (the Beatles sample from which will probably ensure this record never gets an official reissue), "I Got It Made," and "I Am the Magnificent" were the strongest since Follow the Leader the previous year. The album as a whole was strong, though, and helped the Flatbush native transcend humble surroundings, to make the dream of "I Got It Made" a reality.—David Drake

33. Public Enemy, Yo! Bum Rush the Show (1987)

Label: Def Jam, Columbia

There used to be a time, when a rap fan saw the Def Jam logo on anything, including some new group you never heard of, you simply bought the joint because you knew the label never released any junk. Even if it was some go-go banging kids from Washington DC, an R&B diva named Alyson Williams or an uptown soul singer (and former jewel thief) named Oran Juice Jones, one could be sure that the product was fresh. Of course, what Def Jam specialized in was hip-hop that didn't stop, gaining themselves invaluable street cred with a roster that included T La Rock, Slick Rick, LL Cool J, and the Beastie Boys.

Public Enemy was signed at the insistence of Rick Rubin, who was as attracted to main rapper Chuck D's voice as much he was to the noisy layered sound collage of production crew The Bomb Squad—hell, even their name was cool. Chuck was also down with the Squad, calling himself Carl Ryder, which included Hank Shocklee, Keith Shocklee, and Eric Sadler.

Other producers simply made beats, the Bomb Squad assembled musical assaults. Like a visionary heist mob, each man played his position in the studio, with one dude crate diggin' while another programmed the 808, and the outcome was some of most diverse sampled/looped music created during the latter years of the '80s. Although the forthcoming Nation of Millions would be considered the Bomb boy's masterpiece, their debut was nothing to sleep on. If we was talking about R&B, then Yo! would be Public Enemy's Off the Wall while Nation was their Thriller.

Although they would later be known as the Prophets of Rage, rapping smartly about racism and social issues, vocalizing an intellectual worldview that shamed other no-nothing rappers, in the beginning, as heard on "You're Gonna Get Yours," brother Chuck big-upped his ride as much as the next rapper. Except, he wasn't talking about some tricked-out Caddie or Beemer, but instead he had nothing but love for his '98 Oldsmobile. "Get wit it, the ultimate homeboy car," Flav screams in the background as the engine roars and the tires screech.

Employing the rock guitar chops of black metalist Vernon Reid on "Sophisticated Bitch," in which Chuck pops junk to some gold digger who thinks she's all that, he was really at his best when talking about politics or himself. Indeed, while PE would later take on loftier subjects, the self-serving "Public Enemy No. 1," with that ill buzzing sound shrieking throughout the beat, was one of the best boast ("...you can rock the kid, so go cut the cheese...") since Ali stung like a bee.

Although not as militant as they would later become, Yo! Bum Rush the Show still sounds fresh 22 years after its release. With their debut, Public Enemy brought the noise. —Michael Gonzales

32. Ice-T, Power (1988)

Label: Sire/Warner Bros. Records

Probably more famous, at this point, for its awesome-as-awesome-can-ever-be cover image, the second album from pimp-turned-hip-hop-pioneer Tracey "Ice-T" Marrow (who might be more famous himself, at this point, for playing detective Odafin Tutuola on NBC's long-running TV show Law & Order: Special Victim's Unit), 1988's Power should be just heralded, more so in fact, for being an exquisite example of proto-West-Coast gangsta rap. Before N.W.A turned up the volume the next year, and brought the form to car stereos and backyard barbecues all across the country, Ice-T was the leading exponent of rap that detailed the criminal underworld of sunny southern California.

With beats vacillating between the cold electro-funk of "Drama" and "Heartbeat," the warmer blacksploitation-era soul of "Pusher" and "High Rollers," and classic, New York-style breaks of "Power" and "Girls L.G.B.N.A.F.," Ice straddled the line between street amorality and conscious wisdom. On "High Rollers," wherein he paints a glamorous picture of gangster dons—"They dress in diamonds and rope chains/They got the blood of Scarface running through their veins/Silk shirts/Leather suits/Hair always fresh/Eel-skin boots..."—only to turn the song into a clear-eyed warning in a spoken interlude later on. "That fast money leads to a fast life and a quick death. This is my word. This is Ice-T. And I got no reason to lie to you."

Power should be more famous than it is. Simply for being one of the most golden albums from rap's original golden era. —Dave Bry

31. Salt-n-Pepa, Hot, Cool & Vicious (1986)

Label: Next Plateau

Early rap was a boys' club, but U.T.F.O.'s Roxanne Wars blew that wide open as dozens of ladies cropped up to respond to the group's jilted kissoff "Roxanne, Roxanne" in 1984. The next year another battle-of-the-sexes answer record would debut a game-changing force for women in rap as then-unknown group Super Nature clapped back at Doug E. Fresh and the Get Fresh Crew's "The Show" with "The Show Stoppa (Is Supa Fresh)." Super Nature quickly changed its name to Salt-N-Pepa and chased the buzz from "The Show Stoppa" with their debut album Hot, Cool & Vicious.

Armed with eye-catching asymmetrical haircuts (thank a perming accident made good), sharp rhymes and ace beats courtesy of producer/co-writer Hurby "Luv Bug" Azor, Salt, Pepa and their DJ Spinderella curved worthless dudes on "Tramp" and "Chick on the Side" and put rivals on notice with "I'll Take Your Man."

The group really took off when the freestyle-infused "Tramp" single b-side "Push It" unexpectedly broke Top 40, and the album was amended to include Cali DJ Cameron Paul's edit as the opening cut. Hot, Cool & Vicious set Salt-N-Pepa up for a very lucrative career, and its feminist message of empowerment and effortlessly fly ownership of female sexuality are the very DNA from which the Kims, Foxys, and Nickis of subsequent rap epochs were birthed. —Craig Jenkins

30. MC Lyte, Lyte as a Rock (1988)

Label: First Priority Music/Atlantic Records

The significance MC Lyte in the era of the '80s are often overshadowed by the b-boy strides that were being made during the same decade. Yet, coming at a time when rockin' the mic was an equal opportunity profession and all women weren't automatically called "bitches and hoes," MC Lyte emerged from the depths of Brooklyn caring more about her rhyme skills than her make-up.

Spending her youth years listening to her mama's music, which was the swooning soul of Al Green and other down home R&B men, little Lyte's whole world turned upside down after she was exposed to a rap records bumping from her cousin's stereo. Bopping to cuts by the Funk 4 + 1 and the Treacherous Three, from that moment on she knew she was chosen.

Fast-forward a few years later when Lyte was a teenager working with her step-brothers Milk and Giz (Audio Two) to create her first single "I Cram to Understand U (Sam)." Over its minimalist beat, Lyte's lyrically trashed the object of her desire. Even though Sam was a scrub, Lyte loved him till she found out he was just a crack fiend trying to get her green. Although sister girl might've had a broken heart, she wasn't taking no shorts.

In the real world, luckily for Lyte, her pop's started a record company called First Priority, and months later she recorded Lyte As a Rock dropped. "Boom, she sounded rough, rugged and raw," rap expert Chuck D. said about the young girl in the Fila sweat-suit and bamboo earrings. "Kickin' it for Brooklyn," as another one of her jams declared, MC Lyte was soon the rap queen of her borough.

Holding on to her crown while eliminating all contenders, Lyte wasn't scared, because the sharp-tongued wordsmith could hold her own on the microphone. Lyte's follow-up single "Paper Thin" was the phat showstopper, using a dope Prince ("17 Days") sample combined with a with a pinch of Al Green ("I'm Glad You're Mine") that should've halted all rivals, including beat biter Antoinette, in their tracks.

Homegirl might've been Lyte as a Rock, but her debut album was heavy as a boulder. —Michael Gonzales

29. Marley Marl, In Control Volume 1 (1988)

28. LL Cool J, Radio (1985)

Label: Def Jam, Columbia

A ten-ton AC/DC guitar riff cuts in nine times as a seventeen-year-old kid in a Kangol hold a mic up to mouth. "Some girls like to jam/And some girls won't/'Cause I make a lot of money and your boyfriend don't/L.L. what the hell/Gonna rock the bells/All you washed up rappers wanna do this well/Rock the bells!"

And then the go-go drums from Troublefunk's "Saturday Night Live" loop around again and DJ Cut Creator scratches the record with his fingernail. "Rock the Bells," produced by Rick Rubin ("reduced" it said in the credits) is the seventh song on L.L. Cool J's debut album, Radio. The cover image of the album is a close-up picture of a JVC RC-M90 boombox. That's pretty much all you need to know about hip-hop right there. —Dave Bry

27. Eazy-E, Eazy-Duz-It (1988)

Label: Ruthless, Priority

While legacy rap groups like Wu-Tang let their breakout records settle on the public awhile before launching into solo records, N.W.A.'s 1988 gangsta rap landmine Straight Outta Compton was only out a few weeks when Eazy-E stepped out on his own for Eazy-Duz-It. Eazy was coming off a stint as a dealer and crass as any MC working short of Luke and Too $hort early on, and his album is a suitably extralegal volley of street stories and dispatches from the bedroom.

Ice Cube and MC Ren helped out with the writing (with Ren guesting on half the songs), and Dr. Dre and DJ Yella refined what would become the signature sound of Los Angeles gangsta rap on chunky funk workouts like "We Want Eazy" and "Radio," which nicked the killer bassline from disco songstress Taana Gardner's classic "Heartbeat." Hard partying Eazy/N.W.A. debut single "Boyz-n-the-Hood" appears in a cleaned up remix version as well alongside even harder partying slice-of-life tales like "Ruthless Villain" and "2 Hard Mutha's." Eazy-E's solo debut retained all of the Compton group's gun-toting fury without bothering with any of the sobering weight of its social commentary. —Craig Jenkins

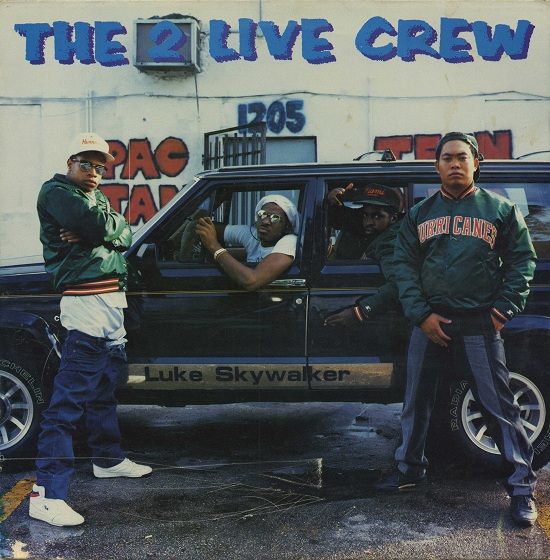

26. 2 Live Crew, Is What We Are (1986)

Label: Luke/Atlantic Records

Before they were platinum stars and the epicenter of a national debate on censorship, Luke Skyywalker and 2 Live Crew were Florida's dirty little secret, creating the blueprint for decades of southern strip club rap. Their legacy will always the filth of songs like "We Want Some Pussy" and "Throw The 'D'," but the reason 2 Live Crew's early music has aged surprisingly well is the inspired alchemy of the production, throwing the bombast of mid-'80s New York hip-hop together with faster Miami Bass tempos and collages of vocal samples (often of the pornographic variety, naturally).

"Mr. Mixx On The Mix!" chops up the Liquid Liquid bassline, and "We Want Some Pussy" follows Run-D.M.C.'s lead of throwing heavy metal guitars over drum machines, but still fresh-sounding tracks like "Cut It Up" show just how 2 Live Crew were ahead of their time as much as they were of their time. —Al Shipley

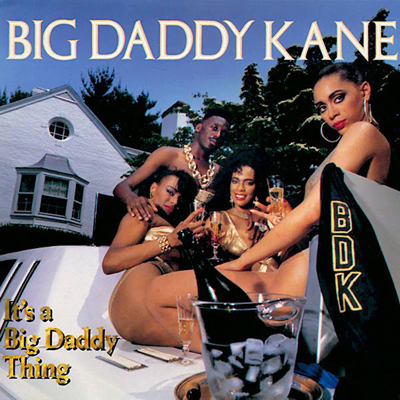

25. Big Daddy Kane, It's a Big Daddy Thing (1989)

Label: Cold Chillin/Reprise//Warner Bros. Records

New York Times music critic Jon Pareles once called rap "audio theater with a dance beat," but the reality was more like a blaxplotation film with a dope soundtrack. Of course, not all rappers had the swag of Shaft or Super Fly, but the Brooklyn bred scrapper who called himself Big Daddy Kane was different. Handsome as Billy Dee, funny as Richard Pryor and cool as Fred Williamson, he was also one of the best rapper/lyricists to ever stomp out of Bed-Stuy. A hero to most, but especially Jay-Z and the late Biggie Smalls, the brother wasn't about half steppin' when it came to crafting songs.

Yet, while his debut Long Live the Kane was more of a Juice Crew showcase, with sonic scientist Marley Marl producing the entire album, for his slamming sophomore effort It's a Big Daddy Thing, he reached out to Prince Paul, who produced De La the same year, Mister Cee (his DJ), Easy Mo Bee on the funky fantastic "Another Victory," and Teddy Riley to enhance his oral pleasures. Kane even managed to bring the heat when producing himself on the slow jam "Smooth Operator," the song that propelled him higher on the sex symbol scale.

Still, it was the collaboration with Harlem native Riley on the slamming "I Get the Job Done" that was an infectious masterwork. A funky joint that dragged you out of your seat the minute Kane starts mumbling in the mix, Riley, whose new jack swing sound was the urban music of the moment, laced the rapper with an aggressive track that the was hotter than dry ice.

On the dance floor, as the females soulfully swooned, soaking-up Kane's chocolate dipped words, the bros could perfect their freaky-deke moves. More than 20 years later, what Kane and Riley achieved on "I Get the Job Done" never loses its appeal. —Michael Gonzales

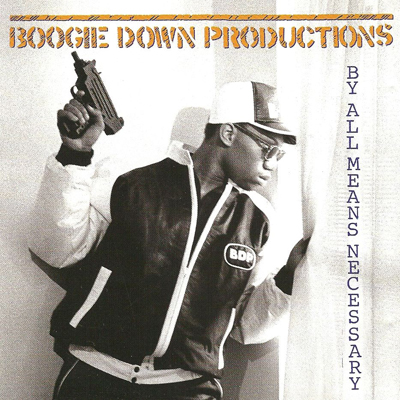

24. Boogie Down Productions, By All Means Necessary (1988)

Label: Jive/RCA Records

By All Means Necessary represented a major turning point in KRS-One's career and life. His close friend and mentor DJ Scott La Rock was murdered right when Boogie Down Productions was on the fast climb to notoriety. KRS moved away from the more violent lyrics like those on "9mm Goes Bang" from Criminal Minded and adopted a more progressive perspective with songs like "Stop the Violence" and "My Philosophy."

Even with the change in attitude, KRS didn't lose his connection to hip-hop's spirit of battle: "KRS One is just the guy to lead a crew, right up to your face and diss you."

By All Means was a shining example of how to properly balance positive messaging with hardcore rap. KRS' revolutionary stance was also captured in the album's cover which was inspired by the iconic photograph of Malcolm X peeking out of a window holding a rifle. KRS One's photo switched out the rifle for an UZI giving it an updated street appeal. To this day, By All Means Necessary remains as KRS One's most powerful albums ever. —Larry Hester

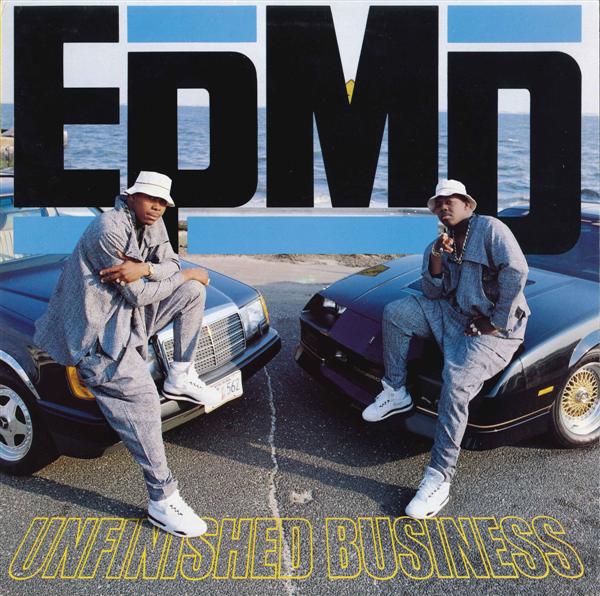

23. EPMD, Unfinished Business (1989)

Label: Fresh/Sleeping Bag Records, Priority

The great thing about EPMD is you don't have to look much further than the scores of ways their sample flips have been borrowed by other artists over the years for evidence of their sphere of influence. On the group's sophomore album Unfinished Business alone you've got "Get the Bozack," whose BT Express sample is the foundation of DMX's breakout single "Get At Me, Dog"; lead single "So Way Cha Sayin'," which was sampled for Mary J. Blige & Biggie's "Real Love" remix; "Knick Knack Patty Wack", whose Joe Cocker sample would figure prominently into 2pac & Dr. Dre's smash "California Love" remix; and closer "It Wasn't Me It Was the Fame", which flips the same Stylistics song Westside Connection's "Gangstas Make the World Go Round" later would.

But Erick and Parrish were more than just smart crate diggers; they were also impossibly cool, collected storytellers who observed their subjects from multiple angles. "Jane II" advanced the giddy sexcapades of Strictly Business' first installment, while "Who's Booty" takes a trip to the darker side of promiscuity. "It's Time 2 Party" is blithesome club fun, but later on "You Had Too Much to Drink" depicts a tipsy ride home turning into a DUI arrest. "Please Listen to My Demo" is about struggling to get on in the rap game, and "It Wasn't Me, It Was the Fame" details the unforeseen troubles you pick up when you get there.

Unfinished Business is a textbook case of second album cynicism, two MCs hurtling through the gauntlet of newfound fame and coming home to let the rest of us know shit's weird out there. —Craig Jenkins

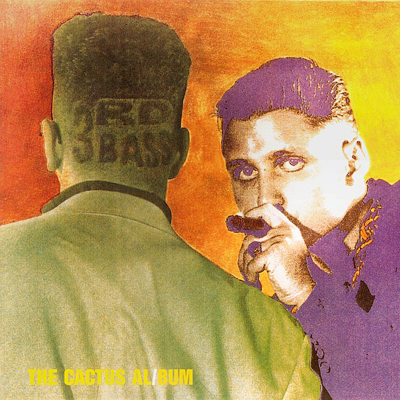

22. 3rd Bass, The Cactus Album (1989)

Label: Def Jam/Columbia/CBS

Back in 1989, when Grammy-winning rapper Macklemore was only six years old, there weren't many white rappers signed to major labels. Over at Def Jam, which put out some of the best-albums during the 1980s golden era, their pale-faced million-dollar babies the Beastie Boys had bounced for greener pastures and more money at Capitol Records and 3rd Bass was quickly given their slot at the sound factory.

Yet, folks who thought that all white rappers were the same were surely disappointed by MC Serch and Pete Nice's dope debut The Cactus Album. First, unlike the Beasties who came from a more punk background and from day one behaved like rowdy rock stars throwing television sets out of windows, 3rd Bass had no electric guitar roots for the crossover folks to connect with; these were cats who'd rather hangout at a dark and dangerous hip-hop spot (Union Square, the Latin Quarter) than be caught drinking from the dirty glasses at CBGBs.

Teaming-up the much-respected crew the Bomb Squad, who had changed the sound of hip-hop the year before with their groundbreaking production on Public Enemy's brilliant It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, 3rd Bass came out kicking like Chuck Norris on their first single "Step into the A.M." Supposedly the track was first offered to Rakim, but he turned it down. Well, the God MCs loss became "the other man's gain" as 3rd Bass nodded to the beat and bounced on Video Music Box.

Next up, fresh from his stint with De La Soul, Prince Paul offered these beige boys a bomb-ass rhythmic romp from his boom boom room, and 3rd Bass emerged with the most energetic diss track "The Gas Face." While throwing real hate at P. W. Botha and MC Hammer (always the most misunderstand '80s rapper), mixed with a little distain for record executives (Dante Ross, Lyor Cohen), they were boogie down tight. Homie Zev Love X, who'd later reinvented himself as MF Doom, also drops a few bars on the beat.

One of the most slept on discs of that decade, The Cactus Album's secret weapon was a then new-jack producer named Sam Sever, who laced 3rd Bass with the heat for their third single "Triple Stage Darkness." In addition, his haunting jazzy soundscape on "Monte Hall" was the disc's crowning achievement. According to Serch, Sever was, "...the reason that The Cactus Album is what it is." Thanks, Sam. —Michael Gonzales

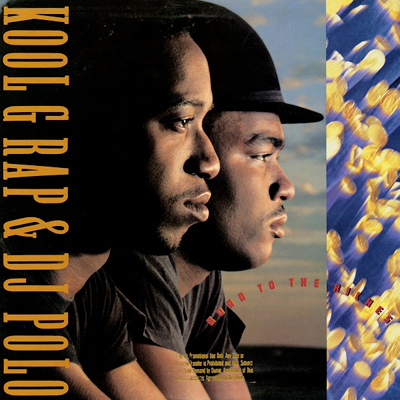

21. Kool G Rap & DJ Polo, Road to the Riches (1989)

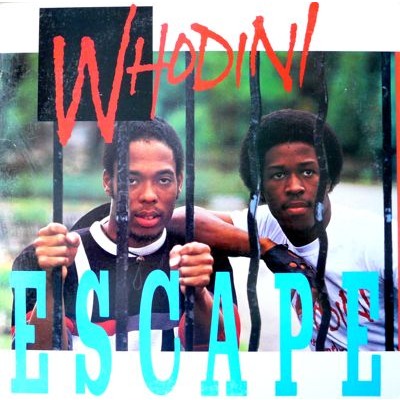

20. Whodini, Escape (1984)

Label: Jive/Arista

Whodini made rap history out the gate with their debut single "Magic's Wand," an ode to rap radio pioneer Mr. Magic that became the first song by a rap act to receive a music video, but the duo of Ecstasy and Jalil (with assists from soon-to-be permanent group DJ Grandmaster Dee) really took off on their 1984 sophomore album Escape. The group refined the elite synthpop edge of their Thomas Dolby produced debut album, teaming up with Run-D.M.C.'s producer Larry Smith to bring a hooky R&B flair to the affair.

From the laid back groove of the bluntly titled "Five Minutes of Funk" to "Friends," a cynical story of betrayal sampled everywhere from Nas' "If I Ruled the World (Imagine That)" to 2Pac's "Troublesome '96" and MF Doom's "Deep Fried Frenz," to harder edged singles "Freaks Come Out at Nite" and "Big Mouth," Escape combined state-of-the-art studio tech, effortless melodicism, and Ecstasy and Jalil's streetwise Brooklyn swag into an early high watermark of party rap. For a minute there, the world was theirs. —Craig Jenkins

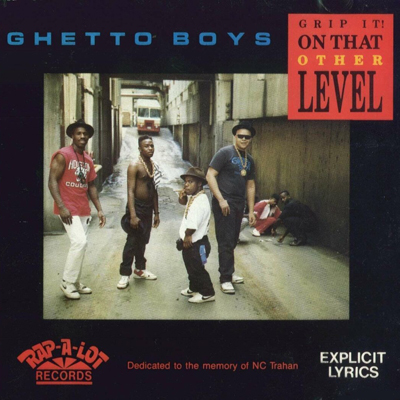

19. Geto Boys, Grip It! On That Other Level (1989)

Label: Rap-A-Lot Records

It was before "Mind's Playing Tricks On Me" put them on the national map, before N.O. Joe and Mike Dean gave them their own distinctive sound, back when Brad "Scarface" Jordan was still going by the name Akshen, but by the time of 1989's Grip It on That Other Level, the Geto Boys had become the Geto Boys: a wholly formed arsenal, ready to bend rap towards the Dirty South.

Composed mostly of beats and flows that adhered to styles pioneered by New York stalwarts like the Juice Crew and Eric B. and Rakim, with most songs serving as a solo showcase for either 'Face, Willie D or Bushwick Bill to express their personal flair, the album nevertheless coheres with itself and shines as its own special kind of thing. It's own special truly appalling, shocking, riveting, thrilling kind of thing, of course.

Kind of remarkable that a full 25 years later, you're hard pressed to find gangsta rap any more horrifically vile, misogynistic or violent in its lyric content. They took it there, all the way there, way back when. Music has never gotten any tougher, or more honest in its depiction of the way a lot of frustrated young men talk when they're together. And amazingly, even for many who might blanch at the language or anger therein, you'd hard pressed to find any that sounds very much better. —Dave Bry

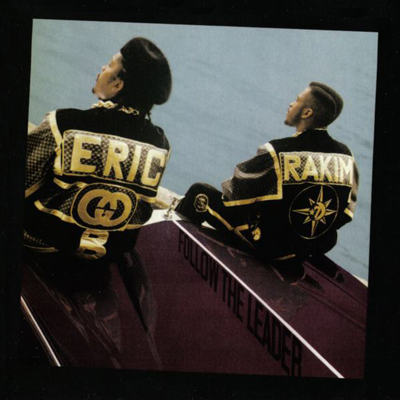

18. Eric B. & Rakim, Follow the Leader (1988)

Label: Uni

Eric B. & Rakim's follow up to their 1987 classic Paid in Full was the grand coronation that fans had hoped for. Prior to Follow the Leader, Rakim rocked over simple James Brown breaks without any intricate production or flair. Not to say that Paid in Full didn't deliver with "Eric B. is President," "Paid in Full," and "I Know You Got Soul"—they were monumental. But where Paid in Full was Eric B. and Rakim's Ford Escort, Follow the Leader was their Rolls Royce.

Follow the Leader was a better produced, mixed and thought out piece of work. The quality was just better. The feeling of hearing the first few bars of "Microphone Fiend" was similar to watching a bully unknowingly pick a fight with a kid who's a black belt in Karate. It's certain that there's going to be some spectacular shit about to happen.

Track after track, Rakim rhymed as if his life depended on it while at the same time making it look effortless as evidenced in his flow on "Lyrics of Fury." Ra weaves in and out of rhythms without losing the beat. One of the skills never seen on the duo's album before it. Critical and street fame pushed Follow the Leader to sell 500,000 copies and backed up outside claims that Rakim was one of the most skilled on the mic. —Larry Hester

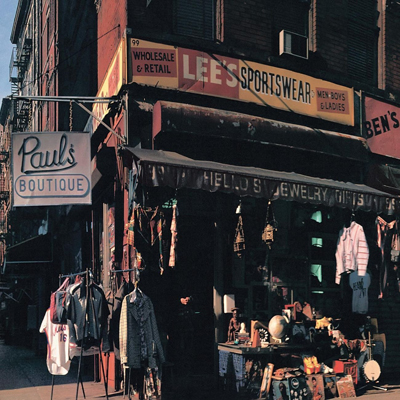

17. Beastie Boys, Paul's Boutique (1989)

Label: Capitol

The Beastie Boys never had trouble banging out incredible albums but Paul's Boutique has long reigned as the trio's most notable releases. Paul's Boutique was no Licensed to Ill album when it came to sales. In fact, initial sales were so low compared to Licensed that Capitol Records threw in the towel and stopped promoting it. That didn't stop the momentum from building.

What couldn't be forecast with sales formulas was the change about to happen musically with sampling becoming more intricate. It was no longer straight loops with a drum machine pattern over it. Sampling got more creative with multi-layered breakbeat loops and chopped samples. The Beastie Boys' aim was right on point with Paul's Boutique, the buzz caught on and appreciation for the album grew consistently. By 1999 Paul's Boutique had sold over two million copies and regarded as a classic.

Experimental in concept, Paul's Boutique made way for the Frankenstein style of production adopted by producers like DJ Muggs of Cypress Hill. The coolest thing about Boutique was that it would have been just as dope as an instrumental album. Had the production team The Dust Brothers (make what you will of the name) stuck to their original plan, Paul's Boutique would have been only beats but the Beastie Boys convinced them to use the music for what became one of rap's most revered classics. —Larry Hester

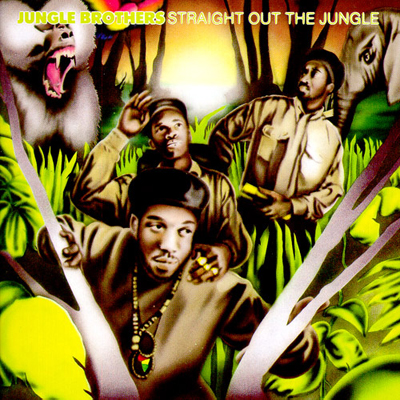

16. Jungle Brothers, Straight Out the Jungle (1988)

Label: Idlers/Warlock Records

While the Native Tongue affiliated group the Jungle Brothers might've rocked Afrocentric gear, wearing African medallions and clothing, they liked to party as much as the next hip-hopper. Indeed, their debut disc Straight Out the Jungle was full of dope dance tracks that made you wanna do the wop. Consisting of Baby Bam and Mike Gee rapping over the jungle jazzy funk supplied by DJ Sammy B, the Jungle Brothers were the first group to wear the Native Tongues moniker with pride. At a time when most b-boys were wearing gold chains and Fila sweat-suits, the Brothers had a more bohemian approach to both their gear and there music.

Back in the 1980s New York City, when folks poured into clubs like Nell's, The World and Union Square, every time the JB's were thrown onto the turntables, especially their classic hip-hop joint "I'll House You," the dance-floors would get crowded. The first record that helped make b-boys discover their inner-Voguer, the single was mixed by acid-king Todd Terry and became a sensation.

While the Jungle Brothers could as nationalistic as Public Enemy, as proven on prideful track "Black is Black," featuring guest rapper Q-Tip, they were still young and under the influence "Jimbrowski." For those not down with '80s hip-hop slang, "Jimbrowski" was their dicks, which they bragged "grew seven-feet tall" and had to be transported in a U-Haul.

More good-humored than crude when it came to both sex and love, their b-boy ballad "Behind the Bush" is still one of love songs ever written in the genre. "I want to be your hero, I want to be your man," Afrika says over a laidback beat of smooth jazz drums and strumming guitars. "I want to love you every moment I can. I want to take you back to the motherland." Indeed, one can almost see the romantic couple wearing kente cloth house slippers and chilling in their hut. —Michael Gonzales

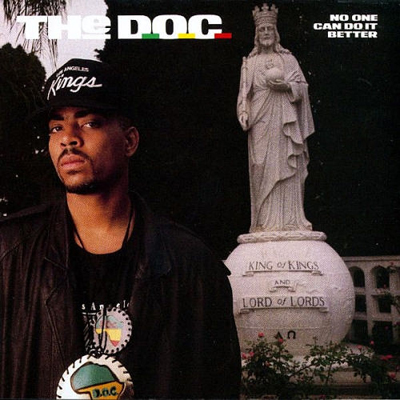

15. The D.O.C., No One Can Do It Better (1989)

Label: Ruthless

Moving from Dallas, Texas to Los Angeles in the 1980s, the D.O.C., a mighty rapper and ghostwriter, joined forces with the then-recently formed Ruthless Records crew N.W.A. Alongside Ice Cube, he began penning lyrics for Eazy-E and producer Dr. Dre, who became one of his best friends. It wasn't long before he became an essential element within the seminal group.

A year after N.W.A's gats, crack, and bitches masterpiece Straight Outta Compton, those hood boyz from Compton worked their mojo on The D.O.C.'s debut No One Can Do It Better. While not as ghetto nihilistic as the rest of the crew, the D.O.C. wasn't all about toting guns, slinging rock, and slapping hoes, homeboy just wanted to have some fun.

Produced entirely by Dr. Dre back in the days when it didn't take him years to construct an album, No One Can Do It Better was funky-using samples from P-Funk, B.T. Express, James Brown, and Sly Stone. Dre hadn't quite gotten the g-funk sound together, but in 1989 we could hear where how doctor was operating as each new project took us closer to the his sonic wonderland.

On the opening track and first single "It's Funky Enough," D.O.C.'s voice was commanding as it glided like black ice over the Foster Sylvers "Misdemeanor" beat. From strip-clubs to sporting events, the song was addictive. The follow-up single "The Formula" had a Marvin Gaye groove that was pure laidback Cali vibe; D.O.C. was at his coolest, riding the Dre-infused "Inner City Blues" beat as though it were a pimped-out Caddie.

Five months after the release of No One Can Do It Better, the D.O.C. was in a serious car accident that nearly killed him. Although he has recorded a few other albums, none matched the gritty beauty of his debut. —Michael Gonzales

14. Biz Markie, Goin Off (1988)

13. Too $hort, Born to Mack (1987)

Label: Dangerous Music, Jive, RCA

Blame The Mack. Indeed, the 1972 blaxploitation film starring cool talking, smooth walking Max Julian as a pimp named Goldie, The Mack made his bread putting his ladies on the stroll while the gangster side of him had to watch his back as rival Pretty Tony (a marvelous Dick Anthony Williams) plotted his attack. Shot in the Bay Area of Cali, for the majority of the flick, when Goldie's not arguing with his Black Panther brother (Roger E. Mosley) and his church-going mama, the Mack was too busy stacking chips, talking shit, and working them honey dips to realize that his demise was inevitable.

The Mack has become legendary in the rap world, influencing everyone from Coke La Rock to Jay-Z. Forget the fact that at the end of the movie, Goldie was broke again and riding a Greyhound bus out of town, the brother had already left his pimp slap on the minds of many young boys who couldn't wait to scream, "Bitch!" as loud as they could.

Yet, no more how many wanna be players step to the mic, few will ever be as tight with their game as Oakland-native Too Short. Coming across like that kid in The Mack who tells Goldie he wanted to grow-up and be just like him, Too Short's classic Born to Mack was like the pimpin' handbook for anyone who want to perfect their skills.

As one can tell from the opening track "Partytime," Too Short didn't have the best voice—it was nasal and whiney—on Planet Rap, but the tales the boy told it was like he was trading stories with Iceberg Slim. On the track "Mack Attack," Short gets the red dice rolling as he goes into big daddy persona. "I'm Short Dawg, ain't nothing nice," he says before slapping some hoe with his bozak.

For the complete album, Short talks slowly about his gentleman's game, but it's the ten-minute long "Freaky Tales" that serves as his masterpiece, serving up his most brilliant observation about the profession he chose. Pimping might not be easy for some, but for Too $hort, the mackin' words just flowed naturally from his tongue. —Michael Gonzales

12. Ultramagnetic MC's, Critical Beatdown (1988)

Label: Next Plateau

By the time Critical Beatdown came out, Ced-Gee of Ultramagnetic was already making a name on the production front. Ced had worked on BDP's Criminal Minded album and was a known wizard of the Emu SP-12 drum machine. With that credibility, Ced-gee roped in Kool Keith, DJ Moe Luv, and TR Love to form the Ultramagnetic MC's.

Ced's innovative beatmaking was shown on tracks like "Ego Trippin" where Ced surgically chopped up Melvin Bliss' 1973 B-side champion, "Synthetic Substitution." Chopping up samples wasn't a completely new thing but Ced was one of the best at the time. His beats weren't just looped break beats, but pieces of breaks weaved together. A technique that would later evolve into the intricate production styles of Q-Tip, Large Professor, Pete Rock, DJ Premier and others.

Combined with Ced-Gee's revolutionary beat patterns, Ultramagnetic introduced a free flowing, syncopative rhyme style that broke the rules of conventional delivery. Kool Keith embraced it the most, making way for the abstract stream-of-consciousness wordsmithing by the likes of Ghostface, Andre 3000, Doom, Lil B and Earl Sweatshirt.

Critical Beatdown wasn't much of a mainstream success but it's still regarded as one rap's greatest works. See, Ultramagnetic was on the Next Plateau record label with Salt N' Pepa. When Salt N' Pepa jumped off, the focus switched from Ultramagnetic leaving the team with little promotion. Although neglected when it mattered most, Critical Beatdown marked a turning point in both lyrical style and beatmaking which is incredibly tough to pull off at the same time. —Larry Hester

11. LL Cool J, BAD: Bigger and Deffer (1987)

Label: Def Jam, Columbia, CBS

From the moment big-headed James Todd Smith bogarted into producer Rick Rubin's office in the classic scene from hip-hop flick Krush Groove, a teenager bopping his red Kagol covered dome on screen as he bellowed over the minimal beat of "Radio," we've known that he was cocky. Of course, in the world of hip-hop being a supreme egotist has always been a plus, so the newly baptized LL Cool J had little to worry about when it came to making his name known.

With the release of his debut in 1985, the Queens, New York native bragged over a beat harder than most boys his age, and the St. Albans-bred MC was just getting started. Yet, for all the love the hip-hop community showered on LL was popping smack on "I Need a Beat," "Rock the Balls" and the title track, he was only beginning to throw down.

While Radio was produced (or, reduced, as the credits read on the back, by Rick Rubin) when LL returned to the lab for his souped-up follow-up Bigger and Deffer (BAD) two years later, he joined forces with Cali producers LA Posse and kicked the ballistics with the West Coast boys. In 2014, everybody works with everybody despite their location, but in 1987, New York rappers never went to the west for nothing except tours and Fat Burger.

Keeping that in mind, both parties the East and the West aurally delivered when it came to constructing the title track first single. Utilizing the funky as a pot of chitterlings "Theme from S.W.E.A.T." music, LL went crazy as his gold "I wish you would" nameplate swung around his thick neck. "Slaughter competition, that's my hobby and job," he proclaimed over the boom.

Far from a sophomore flop, BAD explored LL's wild side ("Bristol Hotel," "Kandy") of his personality as well as the chapstick lipped romancer that we always knew was there. Although many pretended to be disgusted by the sticky icky ballad "I Need Love," that song got more ghetto dudes laid in the '80s than any other record that was on the hip-hop charts. While "I Need Love" pushed LL Cool further to the top of New York City rap, guiding him towards the crossover finish-line, LL rarely lost his swag or his b-boy flavor. Of course, LL ain't the kind of dude you trusted around your girl or your moms, but otherwise, the kid was all right. —Michael Gonzales

10. EPMD, Strictly Business (1988)

Label: Fresh Records/Sleeping Bac Records, Priority Records, EMI Records

This album spent a long time as my default answer to the always-impossible-to-answer question, "What's your favorite rap album." What was it about EPMD's Strictly Business that made me love it so? (And what is it? I do still love it a lot, though my default answer to that question has changed to Raekwon's Only Built 4 Cuban Linx...) It's something about under-ratedness—having that secret perfect gem that you know is a perfect gem but other people don't seem to see its perfection. (Erick Sermon has never gotten the respect he deserves for his production. He is the funk master.)

And it's something about seamlessness and futurism. When Strictly Business came out, it sounded, technical fidelity-wise, about a million times better than anything else that had come before it. Previous rap standard bearers like B.D.P.'s Criminal Minded or Eric B. & Rakim's Paid in Fullhad the grit of city streets in their grooves. I loved that crackly rawness (I still love that, too!) but compared to that, EPMD sounded like it had been recorded in the cockpit of a spaceship. Grade-A choice samples snipped from records ranging the pop music spectrum—Aretha Franklin, Eric Clapton, Zapp, Steve Miller, Joeski Love, Otis Redding, The Beastie Boys, Rick James, The Whole Darn Family—woven into ten songs of smooth, plush, luxuriousness. Like the mixing board in the spaceship cockpit was upholstered with velour.

Rapwise, it was more down-to-earth. Coming off as two pretty regular guys from Long Island who liked Mercedes Benzes, neither Sermon nor his partner Parrish Smith were near the lyricists that KRS-One or Rakim were. They stuck to standard battle rap and boasting. But they were plenty clever and their voices played off the music perfectly. Sermon's stoned, mumble-mouthed reportage ("When I walk through the crowd I could see heads turning/I hear voices saying 'That's Erick Sermon...'/Not only from the women, but from the men/You know what? It feels good, my friend....") volleyed back and forth with P's more traditional, monotone slick talk ("I'm the Thriller of Manilla/MC cold killer/Drink Budweiser/Can not stand Miller/MCs cold clock until the parties through/Then they tap me on the shoulder and say 'This Bud's for you...'") —creating another fluid layer of sound above the hypnotic basslines and spliced-in melodic embellishments.

Maybe that's another reason why this album worked its way into a young rap fan's heart the way it did. EPMD seemed relatable, less godlike than the mystic figureheads of the genre. They were just two friends who made party music. They just happened to do so exquisitely. —Dave Bry

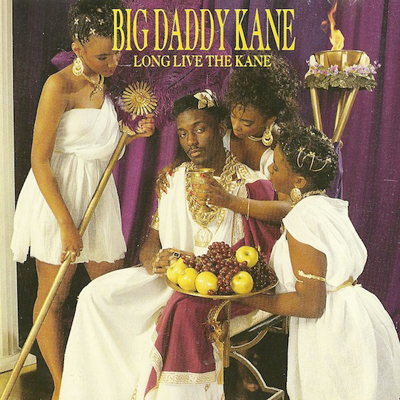

9. Big Daddy Kane, Long Live the Kane (1988)

Label: Cold Chillin/Warner Bros. Records

In the late '80s, when Def Jam Records was making household names out of folks like the Beastie Boys and L.L. Cool, the lesser-known Warner Bros. subsidiary Cold Chillin' Records was home to Marley Marl's Juice Crew—a Queens-based rap collective that, to many connoisseurs, represented the true cream of the hip-hop crop. MC Shan, Roxanne Shante, Biz Markee, Kool G Rap, and a smooth-voiced member of the Five Percent Nation of Islam, who claimed the throne, Big Daddy Kane ("King Asiatic Nobody's Equal.")

Released in 1988, Kane's debut album, Long Live the Kane, stands as a perfect example of what made the Juice Crew so highly revered. Simple, spare, mostly-James-Brown-based break beats that leave plenty of room for Kane rev up and deliver his lightning-tongued battle raps. "I'll just break 'em and bake 'em and rake 'em and take 'em and mold 'em and make 'em," he says of any would-be competition at the end of the classic single "Ain't No Half Steppin'." "Hold up the peace sign/A salaam alaikum..." —Dave Bry

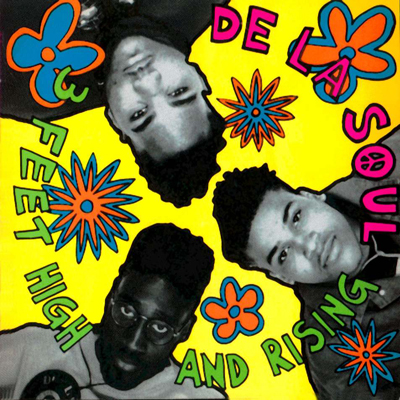

8. De La Soul, Three Feet High and Rising (1989)

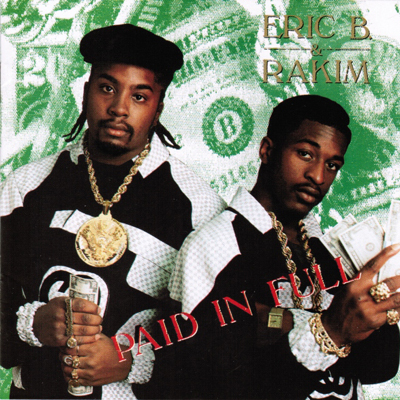

7. Eric B. and Rakim, Paid in Full (1987)

Label: 4th & B'way, Island

It's hard to overstate the importance of Eric B. and Rakim's 1987 debut album, Paid In Full. As the first full-length display of Rakim's rapping, it changed the art form more profoundly than any album before or since. (The art form of rapping itself—the writing and delivery of rhymes. I would say that Dr. Dre's The Chronic changed rap music as a whole more profoundly.)

Rapping has changed a lot over the past 26-and-a-half years. But it's never undergone a more dramatic stylistic shift than it did from the time just before anyone outside of Wyandach, Long Island had heard Rakim's monotone—flowing so smooth, so patiently, so cold, putting words together in such complex patterns—and just after. Paid In Full marks the start of modern-day rap. —Dave Bry

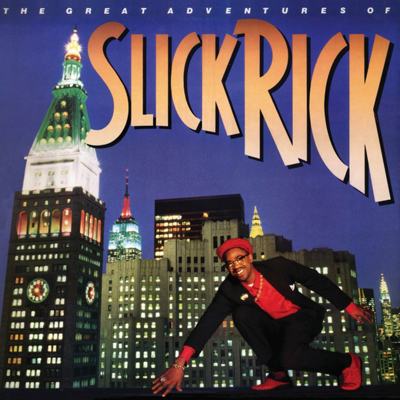

6. Slick Rick, The Great Adventures of Slick Rick (1988)

Label: Def Jam, Columbia, CBS

After the Kangol Crew made up of Dana Dane and Slick Rick broke up, Slick kept his regal English accent in listeners ears by appearing on Doug E. Fresh's "The Show" and his own "La Di Da Di." Slick Rick was the man that people had only heard one-off tunes here and there from so when his album finally dropped in 1987, The Great Adventures of Slick Rick was an instant smash.

Already somewhat seen as an awesome storyteller, Slick Rick's album confirmed his ability to deliver tales that made listeners forget they were listening to a rap song. Sometimes the stories treaded the whymsical in "Mona Lisa" where there was no real point or moral and other times songs like the criminally tragic "Children's Story" that made it a point to deliver a deeper meaning.

Slick Rick wasn't only known for story spitting, Songs like "Treat Her Like a Prostitute" and "Indian Girl" contained some of the most hardcore lyrics recorded at the time. That however didn't stop Rick's crossing over into the mainstream. Over 20 rap and R&B songs sampled pieces from from The Great Adventures of Slick Rick from Montel Jordan's use of "Children's Story" on "This is How We Do It" to TLC's "Creep" which used Slick's "Hey Young World". —Larry Hester

5. Beastie Boys, Licensed to Ill (1986)

Label: Def Jam Recordings, Columbia Records

It's easy to get lost in the political issues that surround this landmark work's history: Def Jam Records releases the first album made by white rappers and it becomes a worldwide smash, selling eight million copies—well more than twice what any previous rap album had sold—and bringing rap music to a much wider audience than it had previously reached. Race and America and cultural appropriation, etc. Heavy conversation.

But that shouldn't blind anyone to the enduring brilliance of Licensed to Ill. Every song on it, from inescapable frat-party classics like "Fight For Your Right" and "No Sleep Til Brooklyn" to less ubiquitous gems like "Posse in Effect" and "Slow and Low," works just the way it's supposed to. And it all still sounds terrific today. —Dave Bry

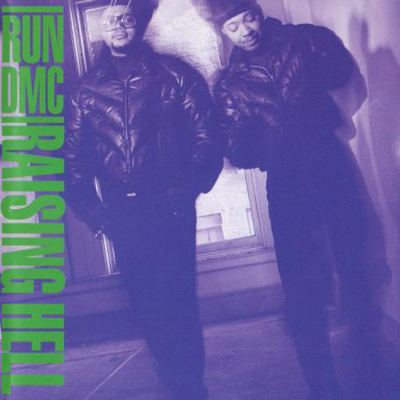

4. Run-D.M.C., Raising Hell (1986)

Label: Profile Records, Arista Records

If you happened to have been in the parking lot of the A&P in downtown Little Silver, New Jersey one sweaty summer night of 1986 and saw two drunk idiot high-school kids standing on the roof of a station wagon, rocking it violently back and forth with their feet while they performed an acapella version of "It's Tricky," the second song from Run-D.M.C.'s third album, Raising Hell, I would like to take this opportunity to tell you that it was not me and James Cash up there making fools of ourselves while our friends tried to get us down before we set off a car alarm or something and brought the cops coming. I don't know who it was. I wasn't there and I don't know anything about it.

The Beastie Boys get a lot credit/blame for introducing white suburbia to the joys/dangers of rap music with their album Licensed to Ill, which came out later that year. It wasn't that so much as it was this. Run-D.M.C. Raising Hell. The original soundtrack for jumping on top of station wagons in A&P parking lots. —Dave Bry

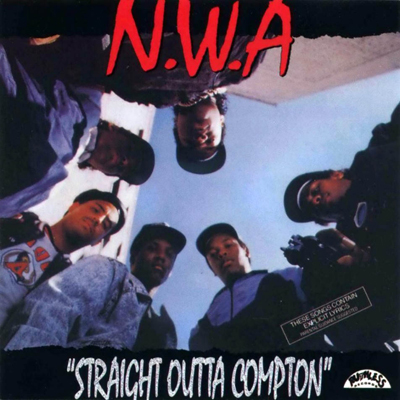

3. N.W.A, Straight Outta Compton (1988)

Label: Ruthless Records, Priority Records, EMI Records

N.W.A. has been credited for both the great and ill of hip-hop depending on who's asked. On one hand, they opened the eyes of listeners who were unaware of the insanity going on in the streets of Los Angeles. On the other, they were the mark of the hip-hop anti-christ who ushered in an era of self-destructive culture.

Straight Outta Compton wasn't supposed to be rap's booby trap and an unbiased re-listen proves it. N.W.A.'s narrative was blunt and biting in delivery. Songs like "Gangsta Gangsta" and "Dopeman" weren't gross celebrations of inner-city tragedy but a hard look into the crooked kingdom of drugs and gangbanging. Each song played out as a story told from a character in a twisted realm of street lore.

Unlike a lot of the gangster-inspired material of today, Straight Outta Compton balanced their brutal themes with songs that fell in line with hip-hop's core foundation with MC Ren's "If It Ain't Ruff," "Quiet on tha Set," and "Express Yourself." These were nods to the group's background in the art proving that they weren't just a bunch of newbies on the mic.

To the mainstream press and political axe grinders, Straight Outta Compton was the death knoll of morality. "Fuck tha Police" put N.W.A. in the crosshairs of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and fans loved it. Cops refused to provide security for concerts and fans wanted more. Straight Outta Compton was one of the first albums ever to get a parental advisory sticker and by the time it was all said and done, the album had sold over 10 million units.

As the rest of N.W.A.'s history played out, their method and message became a tangled mess. So-called reality rap leaned more towards shock value instead of actual content. Even with Eazy-E's Eazy Duz It, and N.W.A. branded releases post the group's break up, the street tales became more cartoonish with pearl clutching potty mouthing and gratuitous violence.

The albums after Straight Outta Compton did great sales numbers but it was apparent that something was different with vibe. There was a certain rebellious, desperation to be heard that was missing and will probably never be captured the same way N.W.A.'s landmark album did it. —Larry Hester

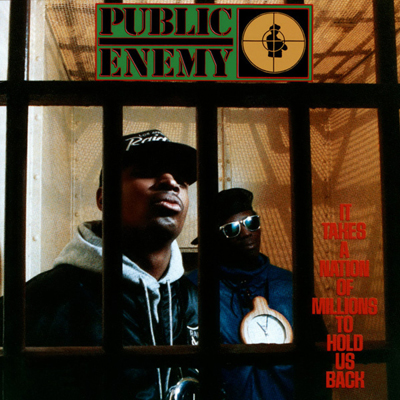

2. Public Enemy, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back (1988)

Label: Def Jam Recordings, Columbia Records

Public Enemy released their jarring sophomore album It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back in 1988—changing the sound of hip-hop for decades to come. The Bomb Squad's multilayered production style departed from the typical one or two looped samples that characterized the work of producers like Marley Marl and Rick Rubin. Hank and Keith Shocklee would mix multiple loops and manipulate a plethora of diverse sounds into a single chaotic groove, the better to capture the raw power of Chuck and Flav's lyrical attack.

The sound was so different that it demanded listeners' attention in the first few seconds, the better to focus attention on Chuck and Flav's lyrical attack. Public Enemy represented an all-in attitude that mirrored the same passion of Run-D.M.C.'s praise of adidas, but applied that passion to far more urgent topics. Chuck D's rhymes on songs like "Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos" blasted government corruption or explored the tragic depths of the crack epidemic on tracks like "Night of the Living Baseheads." This was a completely different approach than the half-assed "crack-is-wack" messages found on so many other songs at the time—and presented the first credible challenge to the glorification of hustlers going on in other corners of the hip-hop cosmos. It Takes a Nation was a harsh commentary on the same issues that aired on the news—only it was coming from the perspective of the common man instead of political pundits.

At the same time, the United States was going through a period of post–crack era paranoia that played out as racial tension. African-American men like Yusef Hawkins, Willie Turks, and Michael Griffith were profiled as thugs and murdered by white mobs. Police brutality skyrocketed as poor neighborhoods got poorer and the school system continued to fail its students, becoming battlegrounds where youth killed each other for sneakers and coats rather than sanctuaries for self-improvement.

There was no voice speaking for all the people suffering the consequences of these crises, aside from civil rights activists like Jesse Jackson who seemed disconnected from what was going on in real time. This societal chaos proved the perfect fuel for Public Enemy's phenomenal rise to popularity. Chuck's booming voice offered the opposite of the pacifist turn-the-other-cheek message at a time when hip-hop listeners were crying out for exactly that.

It Takes a Nation went as far to address music-sampling lawsuits with venomous intent. On "Caught, Can I Get a Witness" Chuck raps, "You scream I sample, but you can sample this? My pitbull." Such metaphorical crotch-grabbing indirectly turned Public Enemy into rap's own civil rights activists. It wouldn't be long before P.E.'s hardcore delivery would expand beyond the African-American and Latino communities and appeal to white listeners with similar grievances. A larger problem with the social and economic set-up was exposed and soon people of all different races united behind Public Enemy's riotous sound.

It was through It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back that hip-hop began to connect the dots and address society's issues in its own way. That's why it still towers over nearly all albums released during one of hip-hop's greatest eras. —Larry Hester

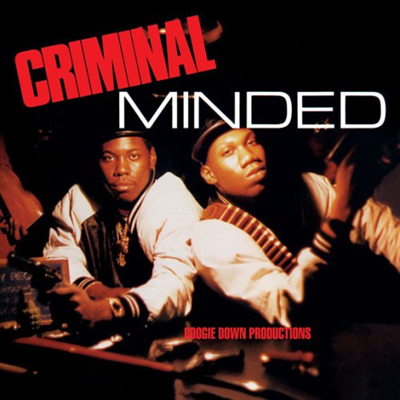

1. Boogie Down Productions, Criminal Minded (1987)

Label: B-Boy Records

Before KRS-One became known the hip-hop icon who over-pronounces his words, he was a young trash talker who helped shape the golden era of hip-hop with Criminal Minded in 1987. You love to hear the story again and again of how MC Shan of DJ Marley Marl's Juice Crew dropped "The Bridge," an ode to Queensbridge's early days of hip-hop, and KRS One responded with "The Bridge is Over." But that was just the warning shot. Soon after dropping that lethal 12", the young Bronx MC, along with his longtime partner DJ Scott La Rock, and, on the low, Ced-Gee from the Ultramagnetic MCs, pulled together jagged fragments of sound from a crazy era to construct a rap masterpiece known as Criminal Minded.

Unafraid to take beef head on, KRS metaphorically threw up his set on "South Bronx"—another shot at the Juice Crew—and a revision of hip-hop's creation myth. KRS, still a teen at the time, popped shit like most teenagers do. On "9mm Goes Bang" he rhymed about shooting drug dealers and popping off at cops. A far stretch from the teacher KRS fans are used to hearing today.

Boogie Down Productions' debut album represents the infancy of New York's hardcore rap scene borrowing from dancehall's rude boy element and the African-American street perspective. Think of the same vibe Black Star, Black Moon and the Boot Camp Click threw down in the '90s and '00s. It was songs like "P is Free" and the album's title track that became the foundation of the BDP sound.

Although KRS rapped from the streets, Criminal Minded was not one-dimensional. Its shape included the DNA of other hip-hop to come, including the genre's internal contradictions. The street mentality, KRS understood, was not a singular state of mind, but a shard of a larger experience. And his art contained a similar totality: "You seem to be the type that only understand/The annihilation and destruction of the next man/That's not poetry, that is insanity/It's simply fantasy far from reality," he rapped on "Poetry." Hip-hop was about the language of violence, but it was also about a lot of other things, too. It was about life. Other obvious contenders as the best rap album of the 1980s, like It Takes A Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back and Straight Outta Compton both came from within Criminal Minded. Its world splintered in different directions as hip-hop expanded.

The album's stripped-down and minimal sound has aged better than most. Maybe ten year ago—in the wake of G-Funk, Puffy's lush disco loops, and Timbaland's juggling rhythmic innovations, the BDP beats sounded stiff and dated. But true art maintains; a decade later in the Yeezus era, that moment feels like a trick of history's lighting. Ced-Gee and Scott La Rock's production holds up track-for-track, a skeleton key for unlocking the genre's potential. —Larry Hester & David Drake