Leslie Murillo is a political rarity. She’s black, Latina, a millennial, and a Republican. That combination of identities may seem incongruous given voting trends, but Murillo insists they’re not. In fact, Murillo has spent a great deal of time over the past few years explaining to family, friends, and others why she, a young woman of color, feels at home in the Grand Old Party. Those conversations are getting a lot harder this year.

“In the Trump days it’s been very difficult to say out loud that I’m a Republican,” says Murillo, a 31-year-old nurse based in Minnesota. “It has interfered with my identity as a black Republican, which was always challenged, always questioned. I can’t even blame the people who are making these insults [now]—I mean, look at who our candidate is."

Murillo has an admixture of beliefs that come together to put her outside of both major parties ideologically: She’s pro-choice, anti-welfare, pro-Black Lives Matter, and against the Affordable Care Act. It’s a set of positions she says she evolved into. Driven by a sense of duty and possibility, Murillo says she voted for Barack Obama in 2008 and watched his inauguration with so much gratitude that she wept. During Obama’s first term, however, she began studying the principles of Democrats and Republicans and thinking deeply about her own values. The more she learned about the conservative tenets of small government, individual freedom and personal responsibility, the more she realized that she was a Republican.

“‘You’re black and you’re a Republican, what’s wrong with you?’”

“‘It doesn’t make any sense.’”

“‘Oh, you wish you were white.’”

Those are the responses Murillo says she gets most often when people find out she’s Republican. Beyond the judgment, though, Murillo is an anomaly as a voter. In fact, she is at the intersection of four groups that lean Democrat. According to a Pew report released last year, young voters like her favor the Democratic Party by 16 percentage points, Latinos lean Democrat by 30 points and blacks by 69 points, and women favor the Democratic Party over the Republican Party 52 percent to 36 percent. Pew also found that just 12 percent of millennial Latinas and only four percent of black millennial women identify as Republican.

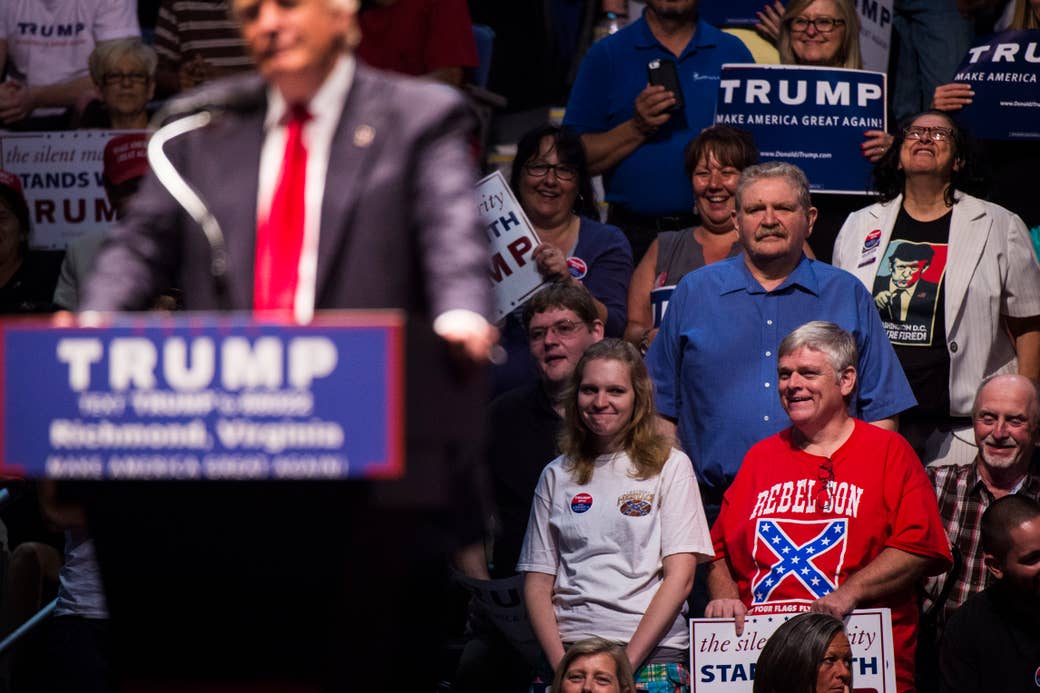

But for many of the young conservatives of color that do exist, Trump’s ascent within the Republican Party has made their already challenged political position feel indefensible. And, although many support the candidate, admire him as a businessman and appreciate his candor, there are others who are dismayed with the way issues of race have been placed front and center in Trump’s campaign. Those most offended say they’ve had their understanding of the Republican Party, and their own position in it, shaken up by the nominee’s many questionable statements and positions. They’re not sure if they’re ready for Trump’s America.

The businessman and reality star did, of course, launch his political career by promoting the lie that the nation’s first black president wasn’t an American. He announced his bid for the White House in a speech that called Mexican immigrants “rapists,” and he’s proposed a ban on Muslims from entering the United States. His outreach to people of color this election year has consisted largely of eating taco bowls on Cinco de Mayo, calls for “law and order” and increasing stop-and-frisk policing, and asking black Americans “What the hell do you have to lose?” For these reasons and others, voters like Murillo say they feel torn about their place within a party that, before Trump, they thought most closely matched their values.

In 2012, Murillo voted for Mitt Romney, but she says she doesn’t feel like she has a real option this November. “The idea of Trump running our country scares me. The idea of Hillary running our country, our finances, and deciding which justices are going to be appointed next scares me even more,” she says.

That’s not to mention the pressure she’s getting from family and friends. With Trump as the Republican presidential nominee, the already-familiar criticisms have become more acidic. Murillo explains that conversations about the election with her husband, who is Native American and a Democrat, have gotten so heated that they avoid discussing politics with each other entirely.

“My husband told me if I vote for Trump he’s divorcing me,” Murillo says. “My brother and cousin have told me that if I vote for Trump, I’m no longer allowed at any of the family cookouts or brunch.”

Despite the fact Murillo disagrees with much of what Trump says, she says she feels obliged to consider voting for him out of loyalty to the Republican party. Still, she admits that she’d be afraid to attend a Trump rally and that she’s found the candidate’s remarks about Americans of color offensive.

“All of us minority Republicans have been blasted and shamed. What he said about Mexicans — my dad is an immigrant,” Murillo says, “He’s not a rapist or murderer. He works.”

Rahul Sitaram, 19, is a business major at the University of Maryland and the son of Indian immigrants. Although he’s a registered Libertarian, Sitaram is heavily involved in the Republican Party at his college and is considering voting for Trump despite the challenges the candidate poses for him personally. Like Murillo, he says the polarized nature of this election cycle has made it difficult for him to express his views publicly on campus.

“The moment that a lot of them hear I’m not a Democrat, they assume that I agree with everything that Donald Trump says. I immediately become painted as a racist,” Sitaram says.

According to Dr. Leah Rigueur, a public policy professor at the Harvard Kennedy School and author of “The Loneliness of the Black Republican: Pragmatic Politics and the Pursuit of Power,” research shows that millennials of color tend to have highly negative views of the GOP and this can make interactions around politics difficult for young Republicans of color like Sitaram and Murillo.

“They’re really this minority within a minority,” says Rigueur. “They’re minorities within their racial group and they’re minorities within their political groups, and oftentimes they complain that their voices are not heard.”

Rigueur points out, however, that the Republican Party has attempted to make inroads with young voters and people of color in recent years. After Mitt Romney lost to Obama, the GOP’s 2012 “Growth and Opportunity” report detailed the fact that the vast majority in those groups had negative views about the Republican party; on top of that, the few young Republicans and Republicans of color already in the party were leaving it. Rigueur says the GOP intended to expand its tent with the 2016 race, but then Trump came a long, shouting a message that has only further alienated the voters Republicans hoped to reach.

“I’ve realized what I want to do with my life, and I really owe that to Trump.” —Angelo Gomez

The Trump campaign’s focus on voters of color and racially charged issues has only intensified as Election Day nears. The candidate recently gave a series of speeches that address what he sees are the issues harming the black community, which he says are living in "hell." Trump has also been visiting black churches around the country and, along with the Republican National Committee, his campaign put together a Hispanic advisory council to reach voters of color.

Leah Le’Vell, 21, is a part of Trump and the RNC's outreach to black voters. The Georgia native, who is black, is taking time off from Georgia State University to work as the committee's African-American initiatives and urban media fellow, tasked with outreach to historically black colleges and universities. Le’Vell cites Trump’s focus on the economy and American exceptionalism as reasons she advocates for him.

“What I like about Trump is his emphasis on jobs,” Le’Vell says. “Especially with me being a millennial and my friends being millennial. When we graduate from college, the first thing we are looking for is a job. We don’t want to stay at our parents’ house after college and not have a job. I think that Donald Trump’s focus is that all Americans get the benefits from the American dream.”

Despite the efforts of Le’Vell and the Trump campaign, the vast majority of young voters aren't warming on the Republican Party’s controversial nominee. In fact, a recent analysis of five surveys by FiveThirtyEight found that only 20 percent of adults between 18 and 29 say they’ll vote for Trump. If that polling holds true on Election Day, it would be the worst performance by a major party nominee among young voters since 1952.

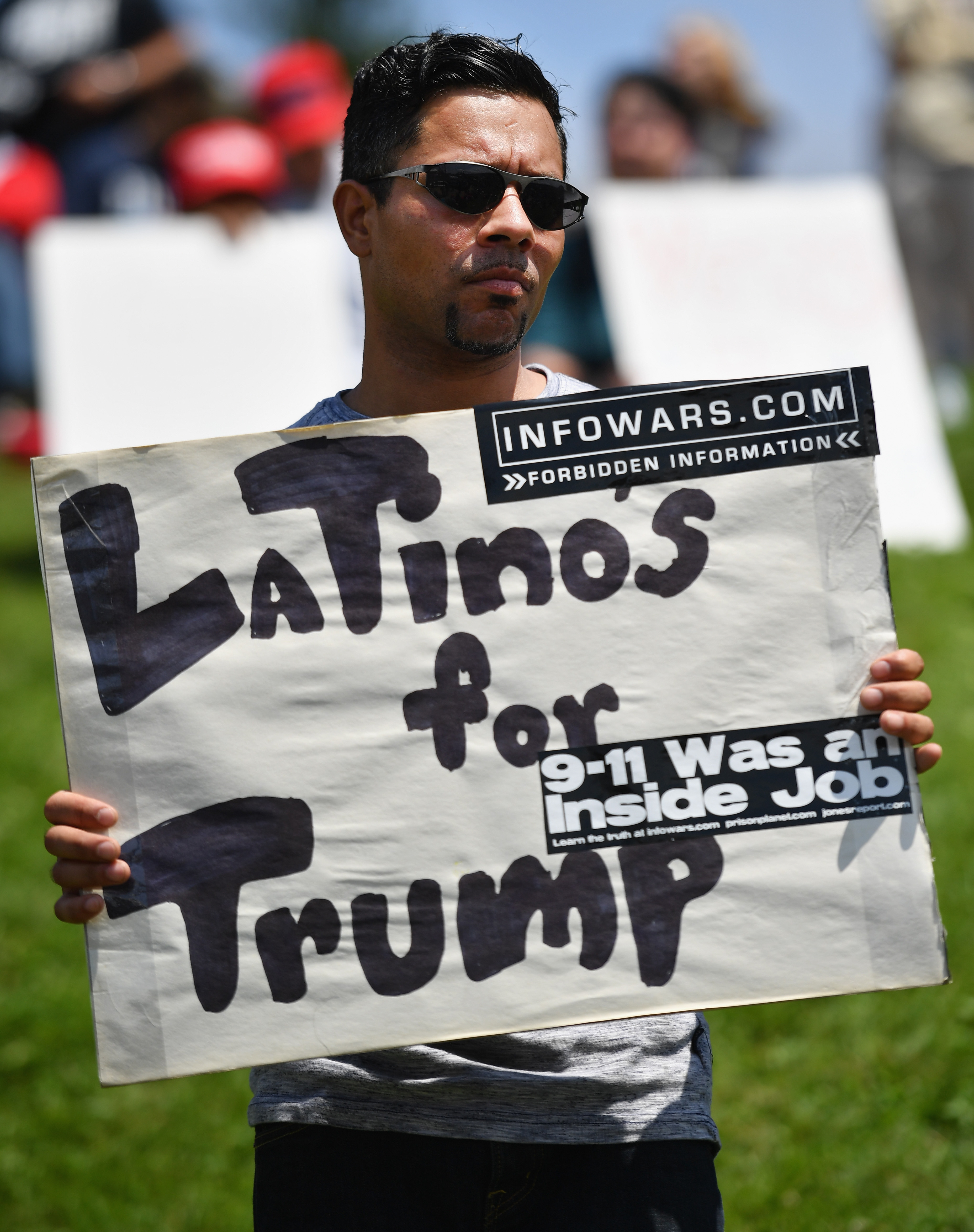

One person whose vote Trump is certain to get on Election Day is Angelo Gomez, an American-born 19-year-old of Nicaraguan and Puerto Rican descent. The slender high school student has spent a good deal of his free time interning at the makeshift Trump campaign office in Las Vegas and says Trump is something of a personal hero to him.

“For a long time, I prayed for God to give me a mentor that can really help me grow,” Gomez says. “With [interning for the Trump campaign] I can see that I’ve grown so much and kind of come out of my shell. I’ve realized what I want to do with my life and I really owe that to Trump.”

Although Latinos like Gomez skew Democratic, Trump has higher support among them than other group of voters of color—which may seem surprising to some given Trump’s comments about Mexican immigrants and attacks on a Latino judge, which even Paul Ryan, the Republican Speaker of the House and a Trump endorser, called “the textbook definition of racism.”

Gomez says Trump’s words were taken out of context and insists that he’s ultimately a candidate who wants to help all Americans. Gomez believes so much in that message that he’s become a leading voice for the candidate online. His social media profiles are dedicated to the GOP nominee, and when a jubilant Trump took the stage at the South Point Arena in Las Vegas to address cheering supporters in February, Gomez was seated behind him, looking on in awe. He got to meet and talk to his idol at the rally, and he'll never forget it.

“To finally meet him, and for him to give me the respect that he did when I looked him in the eye, to listen to every word that I was saying, that was just a very magical experience,” Gomez says. “It was probably the best moment of my life—I look up to him so much.”

“We can’t be the party of white men, and I believe that’s really what it’s turned into, especially now with Trump." —Leslie Murillo

Leslie Murillo sees danger where Gomez sees a mentor, however, and as Trump’s vision for America has become clearer in recent months, she says it’s become more apparent to her that his dream for America would be her nightmare.

It was the issue of policing that sent her over the edge. After hearing Trump advocate for broken windows policing policies in neighborhoods with high crime, Murillo says she finally decided there is no way she can bring herself to vote for her party’s candidate.

“With the stop-and-frisk, that is where I draw the line,” she says. “My brother is black. When I have children I’m going to have a black child, and if I have a black son I don’t want anybody frisking him because he’s black—and let’s face it, that’s what stop-and-frisk is.”

For now, Murillo says she plans to write Ted Cruz’s name on her ballot as a form of protest. And while many Trump supporters are looking forward to November, she’s considering what the Republican Party will look like when he’s gone.

“We have to figure out a way to reach more than one type of people,” Murillo says. “We can’t be the party of white men, and I believe that’s really what it’s turned into, especially now with Trump. Post-Trump we’re going to have to define our party yet again.”