The world was a very different place in 1995: Michael Jordan returned to the NBA following a 17-month retirement, Mike Tyson got out of prison, and Bill Clinton was president. But in Washington, D.C. this past weekend, onlookers may have thought they were experiencing déjà vu.

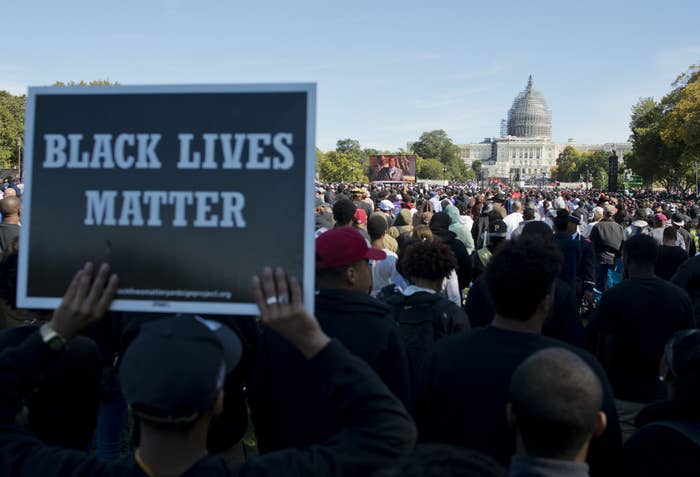

Hundreds of thousands descended on the National Mall Saturday to attend the Justice or Else march, a rally organized by Louis Farrakhan, leader of black nationalist group Nation of Islam. They gathered to mark the anniversary of the Million Man March, a massive civil rights demonstration by black men in the very same place 20 years ago.

But recent police killings of unarmed black people made Justice or Else as urgent as it was commemorative. Indeed, many of the social problems that galvanized the 1995 march, including police mistreatment of African-Americans and the black community’s lack of cohesion, persist today.

Wedged between Rodney King’s 1991 beating at the hands of Los Angeles police officers (and the subsequent riots following the officers’ acquittal) and James Byrd, Jr.'s racially motivated murder in 1998, the Million Man March took place on Oct. 16, 1995.

The march was decades in the making, a volcanic eruption of frustration that had brewed since the Civil Rights Movement. But it was also a reawakening for the black community, a chance to regroup after years of pain. Conceived as a “day of atonement reconciliation, and responsibility,” it called on black men to demand justice and rise up to leadership roles.

Coupled with the O.J. Simpson murder trial that kicked off 1995, race in America during this time reached hair-trigger levels of sensitivity, dividing the country along black and white lines. The climax arrived that October, when Simpson was found not guilty less than two weeks before the Million Man March.

It’s hard not to feel a mixture of rage and despair when you’re mourning someone who looks just like you.

Socioeconomic factors also drove the march’s call to action. According to The Associated Press, black men accounted for 31 percent of all arrests in 1994, and the unemployment rate for that group was 8.1 percent in 1995. Meanwhile, only 73.4 percent of black men graduated from high school in 1995.

Twenty years later, lingering inequality, the recent untimely deaths of black men and women at the hands of police, and the miscarriage of justice for victims’ families, have thrust the question of whether black lives matter back into the limelight. But whereas the circumstances leading up to the Million Man March were a slow burn, Justice or Else was propelled by several painful incidents that occurred over a short period of time.

High-profile deaths in the past year, including those of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, Freddie Gray, and Sandra Bland, all provoked outrage in the black community. Dylann Roof’s massacre at the oldest African Methodist Episcopal church in the Southern United States left nine dead and a country in mourning. George Zimmerman’s 2013 trial, in which he was acquitted of killing unarmed black teen Trayvon Martin the year before, was the most racially charged since Simpson’s nearly 20 years ago.

Justice or Else was an impassioned response to both overt and systemic racism. It was also an opportunity for young people who grew up in the intervening years between both rallies to carry on the activist torch.

More inclusive than the Million Man March (women and other ethnicities were welcome), Justice or Else attracted more youth than its predecessor.

During his speech on Saturday, Farrakhan, now 82, emphasized the importance of recognizing this new generation of activists. "We who are getting older ... what good are we if we don't prepare young people to carry that torch of liberation to the next step? What good are we if we think we can last forever and not prepare others to walk in our footsteps?" he asked rhetorically.

Perhaps young people felt compelled to participate because they recognize themselves in the victims. It’s hard not to feel a mixture of rage and despair when you’re mourning someone who looks just like you.

That’s what makes this video of Howard University students (some of whom might not have been alive in 1995) chanting Kendrick Lamar’s "Alright"—2015’s answer to "Dancing in the Street," a 51-year-old civil rights anthem—so powerful:

Chants of @kendricklamar's "Alright" echoes down 7th street downtown. #JusticeOrElse pic.twitter.com/f1R62P0bIi

The song’s refrain of "We gon' be alright" applies to everyone who gathered at the National Mall on Saturday. Young or old, we’re all looking to bury our anger in the comfort of a better future. We desperately want reassurance that things are going to be alright.

Get used to reading writer Julian Kimble’s opinions, here. He’s not going anywhere. Follow him at @JRK316.