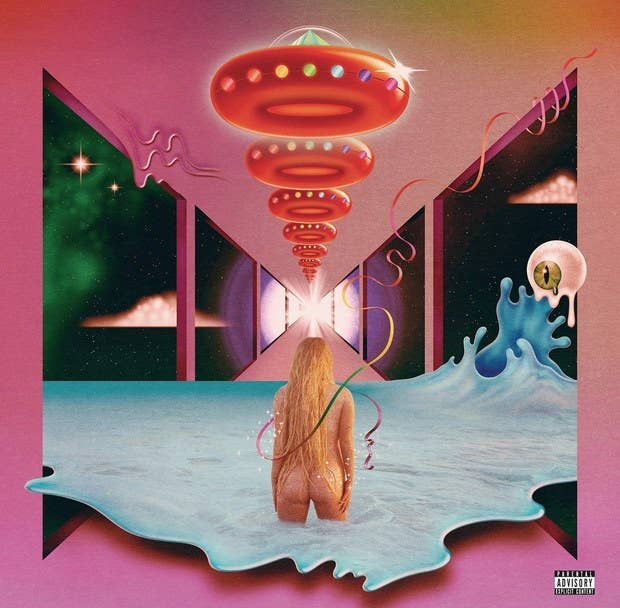

Kesha's new album isn't coming out the way she—or anyone—would have hoped. In the tradition of many artists before her, she fought against her label, in this case Kemosabe’s corporate owner Sony, to release an album that was stuck in limbo. Rainbow breaks with the EDM-influenced party-pop that made her famous, at a time when her cultural relevance is rapidly waning (her last album came out five years ago, which is closer to fifteen in pop years). The difference between, say, Prince or Fiona Apple or Lil Wayne’s standoffs with executives and Kesha’s is a grim layer: She alleges that Dr. Luke, her longtime producer and the former head of her label, sexually assaulted and in other ways insulted and degraded her even as he helped engineer her rise to radio domination—a narrative that sadly echoes Tina Turner’s relationship with Ike Turner, and suggests that an industry that prides itself on political progressivism is still hiding many skeletons in its closet.

The highly publicized and ongoing legal war between Kesha and Dr. Luke, with whom she's still under contract, also threatens to overshadow a remarkable creative departure for the singer. People are shocked at how well Kesha Rose Sebert (the artist formerly known as Ke$ha) sings without Dr. Luke's often-tasteless use of Auto-Tune, and at how comfortably she fits into the roots rock and country music that dominate Rainbow, as evidenced by the video of people losing their shit over her vocal run on lead single “Praying.” They shouldn't be: For those who have followed her closely, and without dismissing her trash-glam aesthetic as merely nonsense, Rainbow is the fulfillment of the not-so-secret ambitions she’s held all along. Kesha has given us many signs before that this is exactly the album she wanted to make, which she’s confirmed in interviews since. “This is truly from the inside of my guts,” she told The Guardian of Rainbow. That she pulled it off so seamlessly is the real surprise.

Kesha has always been underestimated as an artist, which is no surprise. She emerged in the public spotlight as the singer responsible for the hook on Flo Rida's dumb and insanely catchy club hit "Right Round," then became known around the world for celebrating the joys of brushing her teeth “with a bottle of Jack" on her number-one debut single "Tik Tok." Not exactly promising signs for a long and fruitful career as a singer-songwriter.

But that’s what she has in her bones: Kesha’s mom is Pebe Sebert, who is best known for writing hits performed by the likes of Dolly Parton, a fact that was largely ignored until Pebe became a central player in her daughter's lawsuits. The Nashville girl in Kesha has peeked out before in lyrical shoutouts to Trans Ams, open highways, Daisy Dukes, and cheap bourbon. Before Lorde declared herself too cool for Cristal and Maybachs, Kesha wrote off the trappings of material success for a simpler kind of happiness you can find down a Tennessee dirt road: On “Sleazy,” which has an excellent remix featuring fellow Southerner André 3000, she turns down a guy’s “brand new Benz” in favor of a basement party: “I don't care if you stare and you call us scummy/’Cause we ain't after your affection and sure as hell not your money, honey.”

She’s worshipped rock idols from the start, name-checking the Rolling Stones and Lynyrd Skynyrd in her hard-living anthems. On her last album Warrior, she enlisted Iggy Pop to provide vaguely provocative dad-jokes on the stomping, guitar-driven “Dirty Love,” and liberally aped Phil Collins’ “In the Air Tonight” for “Love into the Light,” her ode to spiritual healing and ‘80s drum fills. She collaborated with the Flaming Lips on the largely acoustic, angelic “Past Lives.” The sound of the Strokes on “Only Wanna Dance with You” was a jarring, worlds-colliding moment for everyone. The album was clearly the product of an artist eager to push against the boundaries of her public image. She even had a name for it: “cock-pop.”

There’s been emotional depth and introspection under the surface of Kesha’s work, especially in the heartache of ballads like “Stephen,” “c u next tuesday,” and “The Harold Song.” (“I would give it all to not be sleeping around,” she pleads on the latter, exposing the raw vulnerability behind her party-girl front.) Coincidentally or not, Dr. Luke didn’t have a hand in writing any of those tracks. Pebe helped Kesha dip her toes into tender country-pop on Warrior’s “Wonderland,” a metaphor for lost innocence that could’ve been a hit for Taylor Swift. But Kesha has never been promoted like Swift; until this year, her label hasn't pushed any of her ballads as singles. That dollar sign in her name became prophetic: Sony was far too happy with what it had going to recognize the commercial possibilities of the artist it actually had on its roster.

The joke is on Sony: “Praying” debuted in the Billboard Top 40 and has only moved up the Hot 100 chart in the past four weeks. Though she’s swapped sonic palettes and collaborators, Kesha’s pop savvy hasn’t gone anywhere. (And while Dr. Luke may be persona non grata in many corners of the industry, he still stands to benefit from any future success she has.) “Praying” rips a page from the Adele/Sam Smith playbook, building from only piano to drums and a choir to deliver its gut punch. It resonates because Kesha has the vocal chops to sustain it; there’s no denying the power of that wail, seemingly pitched to the heavens, as she tries to let go of hate for her abuser.

Only someone with Kesha’s omnivorous taste could understand the strange alchemy of getting Macklemore’s right-hand man Ryan Lewis, soul band the Dap-Kings, hip-hop producer Ricky Reed, Eagles of Death Metal, Ben Folds, and Dolly Parton in a room together. (The Queen of Country joins Kesha on Rainbow for a gussied-up cover of “Old Flames Can’t Hold a Candle to You,” co-written by Pebe, which Parton made a number-one country hit in 1980.) On paper, Rainbow looks like a mess. But when you listen to it, everything somehow fits. It’s one of the great rebirths of pop music.

The strongest connection between the old Kesha and the new one is her personality. Her sense of humor and charm are irrepressible—Dr. Luke couldn’t give them to her, and he can’t take them away. Kesha has been inevitably compared to Katy Perry over the years because neither takes herself too seriously. But Kesha’s self-deprecation is on another level. (In case you have any doubt, this is the woman who appeared glitter-smeared on the cover of a club remix compilation titled I Am the Dance Commander + I Command You to Dance.) “I know that I'm perfect, even though I'm fucked up,” she sings on Rainbow’s “Hymn,” preempting anyone who would try to shame her for her behavior.

She also just has more wit than many of her peers. A vintage Kesha pun like “I’m just not hooked on your Phonics” is a cut above any warmed-over Perry one-liner. Both artists have stirred controversy for political incorrectness, but Kesha seems in on the joke of her (often hilariously) silly lyrics. Even if you recognize the potential for offense, it’s hard not to laugh when she deadpans on Cannibal’s “Grow a Pear,” “And no, I don’t want to see your mangina,” or tells off a skeevy older dude on Animal’s “Dinosaur” by screaming, “Get back to the museum!” On the cheeky new country track “Hunt You Down,” she tells a guy, “Baby, I love you so much/Don’t make me kill you.” You can practically see the glint her eye.

Kesha has new comparisons to contend with, too. Critics have tied Rainbow to Lady Gaga’s 2016 album Joanne, ostensibly because they both trade in folk and country tropes. But Kesha’s album is far more diverse in its influences, and dives into them headfirst—while she’s been signaling toward such a shift for years, New York City native Gaga dons roots music the way a Broadway star changes costumes. Kesha’s delivery, whether soul-baring (as in the country-ballad opening of “Bastards”) or unapologetically rambunctious (the na-na chant that finishes the same song), is natural.

Still, Rainbow is far from perfect. There's already a hesitancy in the music press about lobbing criticisms against the album, given the loaded context in which it’s being released. But it's important to be able to separate art from artist, even if the artist’s intentions are noble. In trying to abstract her own painful experiences for universal impact (and probably to avoid commenting on active litigation), Kesha sometimes resorts to mushy self-help language. While “Hymn” movingly speaks to kids who feel aimless, pop lyrics don’t come more standard-issue than its opening couplet: “Even the stars and the moon/Don’t shine quite like we do.”

Kesha succeeds in her loftiest goals for Rainbow, however. It’s a bold and convincing next chapter from an artist who's been working toward this all along. And now that she has the space to deliver it, she’s finally shown up the people “left to prove wrong” she refers to on “Bastards.” For anyone who questioned whether Kesha should be taken seriously, the answer is definitively yes.