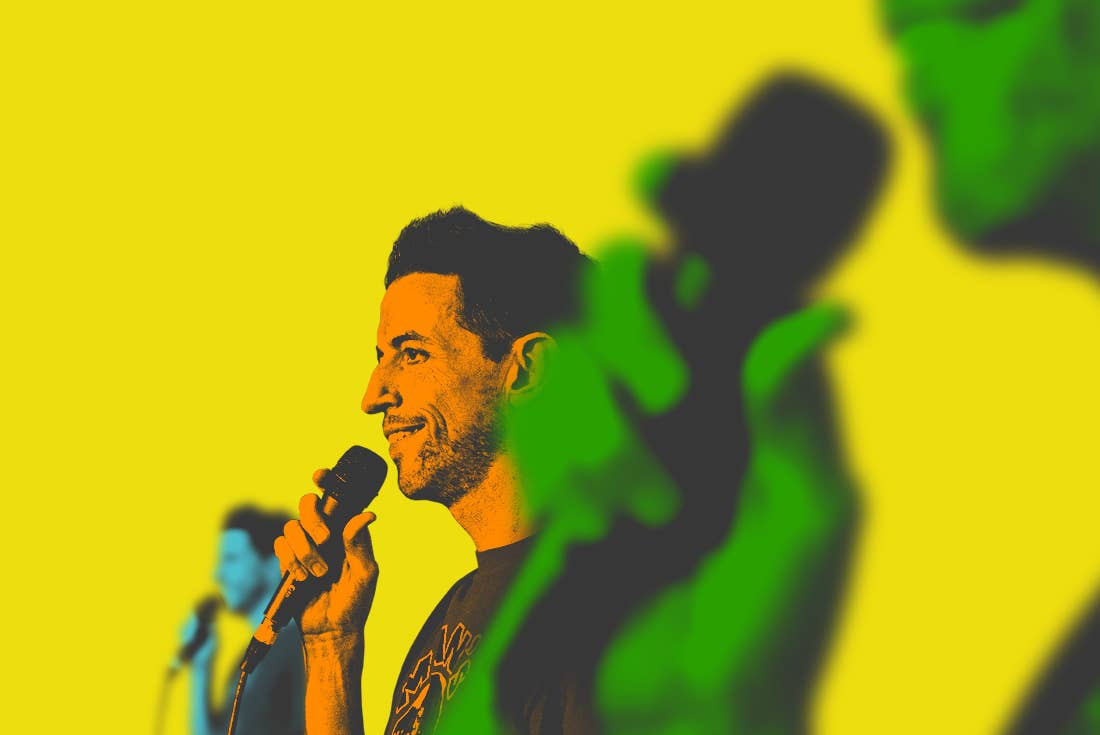

On a Tuesday night at the Lynn Redgrave Theater, a small stage in Manhattan, the comedian Neal Brennan was previewing his new stand-up routine, titled 3 Mics, which isn’t your typical stand-up routine at all. The crowd was littered with celebrities, including Daily Show correspondent Hasan Minhaj and Chad Coleman, of The Wire and The Walking Dead. Coleman, a bit drunk, was playfully heckling and laughing at volumes that disrupted his friend Brennan’s concentration. Brennan, perturbed, was forceful enough to shush and politely shame his friend into some approximation of silence. Quiet, Chad, this is serious.

Comedians are a sad lot; that their currency is laughter suggests emotional buoyancy that many comedians lack. (Richard Pryor and transcendent oddball Robin Williams are just two tragic examples of when these personal demons take control of a comedian’s life.)

Brennan seemed to be channeling the late Robin Williams with his new one-man show, which is currently in a brief run in New York City. 3 Mics is stand-up in literal form, if not quite in spirit; the show is two parts comedy, one part therapy, split across three microphones, total. The setup is simple: three microphones are set across the stage. The mic on stage right is reserved for Brennan’s punchy one-liners. At stage left, he banters in a conventional routine. But at the center mic, Brennan recounts his childhood, discusses his lifelong struggles with depression, and commemorates his late father in resentful detail.

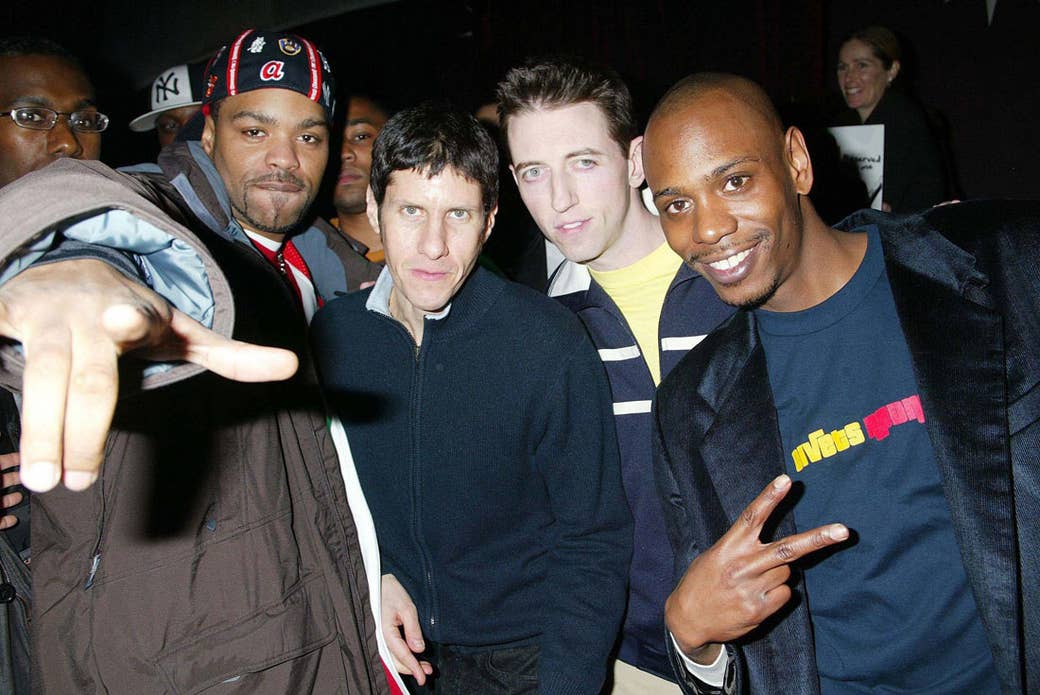

Brennan is mostly known for co-creating Chappelle’s Show a decade ago, and for his own podcast, The Champs, which he co-hosts with Moshe Kasher. A week before the hard launch of 3 Mics at the Lynn Redgrave Theater, I met up with Brennan to discuss his newly patented blend of comedy and tragedy, the recent finale of his The Champs, and the perils of being a comedian in the age of social media backlash.

3 Mics isn’t a conventional stand-up pitch. What’s the tone of this thing?

I’m talking about depression. I’m talking about celebrity. I’m talking about family stuff. Before that, I do fifteen minutes of stand-up. I do one-liners that are palate cleansers, and then I repeat the cycle.

It seems to work as a whole thing. I think maybe the first thirty seconds of the serious parts are a little rough, but by the third serious bit, people are like, stop doing stand-up, I just want to see that. The middle mic: that’s the one. That’s what people care about. The center mic is all horror. It’s torture. Thankfully, I have these other two.

I’m still being funny in the middle mic. It can be heavy, but I don’t really play it for sympathy, and I don’t milk it much. It’s not soporific. It’s not treacly. It is emotional without being sentimental.

Why is sentiment a bad thing?

Sentimental is not bad, but it’s probably the most likely to go awry. It’s the hardest to do and not have it end up being Forrest Gump or something. Maudlin—I just don’t want it to be maudlin.

Who’d you workshop your material with? How’d it all come together?

I just sort of did it [myself]. I did it on Meltdown, the Comedy Central show, which takes place at a comic book store in L.A. They said, we’re doing a standup show, and we don’t want it to be conventional; if there’s anything you ever wanted to try, try it! So I put three mics on stage. It was popular for their show, So then I did it [elsewhere] in L.A. It’s trial and error, basically: what feels pushy, what feels hacky, what I don’t feel like saying in public.

“white people are largely wrong about their approach to race. Almost without fail.”

That’s a strange reservation for you. I listen to The Champs.

Which is retired, by the way. We’re retiring it.

Since when?

Six months ago. Moshe was away, and then I was away a bunch, and anyway we’re out of dudes. People don’t like doing podcasts.

Guests don’t like doing them?

Yeah, and so you just feel like a mooch all the time. I couldn’t fucking ask Kevin Hart, you know what I mean? I only wanted to interview people that were popular or famous or that I was friends with. I just got sick of asking people.

You got thousands of hours of good shit out of people.

I think it served its purpose.

I really thought the Alan Hughes interview was fantastic.

There were so many good interviews. Too Short was fantastic. Questlove did one, we’re going out on that. He wanted to do the last one—he was the biggest fan of the show. He was great. But he literally got lost for an hour and a half. He got lost for an hour and a half, then he got there at like, midnight, and we churned it out. He gets no sleep anyways.

I was with Katt Williams recently, in Nashville, following him around a golf course. I asked him whether comedians are overly sensitive to certain types of fans who are, themselves, overly sensitive to certain types of comedy.

I know what you mean.

What do you think?

If you have feedback, that’s fine. It’s when these people try and advocate.

My buddy Kurt Metzger goes and says wild, hilarious shit on his Facebook page, and then people try and get him fired from Inside Amy Schumer, where he writes. He’s not an elected official. He’s just a guy. Even if you don’t like what he says, Amy Schumer must like some of what he says.

I’ve never heard a joke and thought, fuck you, motherfucker! I’ve heard jokes and thought, ah, don’t say that; that’s fucked up. And the whole punching up vs. punching down... I think that both sides are not being realistic. You can say whatever you want, but there’s going to be consequences to it.

Not everyone’s a politician. There’s these culture police going around and writing people up. It’s the morality squad.

I remember the exchange you had with Ta-Nehisi Coates. About Tarantino, right?

He thin-sliced me and used one half of a quote. One half of a sentence. Mike Epps said that I, a white boy, shouldn’t be writing what I was writing. My contention was that it’s a silly thing to say because Quentin Tarantino—I said, “Quentin Tarantino is the best black writer; he writes the best black characters.” The adjective “black” I meant one way, and it was taken another way. So Ta-Nehisi writes me up. We ended up having a long email discussion that was really interesting. I don’t agree with him in that case.

Do either of those mics feel especially difficult to address given the sort of controversies we’re talking about here?

No. It’s just so personal.

I’m in an odd position where people turn to me sometimes to talk about race. I can do it with some acuity or whatever. I can write for people, but I’m coming at it from an outsider’s point of view. For Chris [Rock], I worked on Top Five, and I sent him some jokes for the Oscars.

With 3 Mics, there’s nothing I’m talking about that’s too hot button. I added a bit where I say that black dudes actually love how openly sad I am because black dudes aren’t allowed to be sad in America unless they express it with a saxophone. That’s about as presumptuous as I get. It’s as close as I can get to the black side without being on that side of things.

I think white people are largely wrong about their approach to race. Almost without fail.

3 Mics is running at New York's Lynn Redgrave Theater, Tuesday through Saturday, through April 9. You can buy tickets right here.