This week in Paris, on Wednesday, three armed men in ski masks broke into the headquarters of the left-wing weekly newspaper Charlie Hebdo and killed ten staffers, including the editor, Stéphane Charbonnier, known as "Charb," and three cartoonists, who worked under the names Wolinski, Cabu, and Tignous. Two police officers were also killed, bringing the death toll to 12—an especially shocking number in France, where gun violence is not as commonplace as in the United States.

Watching from a distance as a tragedy happens to the staff of a newspaper I've read feels horrifying and unreal. When I first heard of the news I felt unsettled, like the air was buzzing around me. After sitting and trying to process the events, I turned to Twitter to look for updates. The hashtag #JeSuisCharlieHebdo ("I am Charlie Hebdo") was trending. The AFP reported that 100,000 people gathered all over France to protest the killings and stand in solidarity with the victims’ families.

But many also reacted with racist statements, lumping the Muslim community in with the three gunmen, who reportedly shouted "Allahu akbar" (God is great) during the attack. One horrifying tweet stated: "This is why people are becoming racist, that Le Pen [a far-right, anti-immigrant politician] is getting votes, that people are Islamophobic!"

C'est a cause de sa que les gens deviennent raciste, que Le Pen prend des vois, que les gens deviennent islamophobe ! #CharlieHebdo

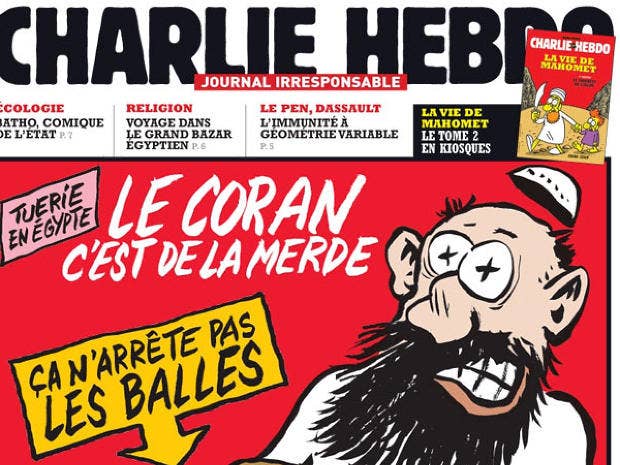

— XIX.V.MMXIII. (@BibiSaroush) January 7, 2015The attack has unleashed a lot of political strife about free speech and the perception of Islam. Not unrelated, Charlie Hebdo has a peculiar relationship to the Muslim community, to say the least. The weekly, which was founded in 1970 under the slogan "An Irresponsible Paper," is famous for its muckraking reporting and controversial political cartoons. Charlie Hebdo presents itself as a wild card dispensing edgy, politically incorrect "equal opportunity" humor.

Along with the latest political scandals, the bulk of jokes pick on Catholic priests who abuse children, or, for the most part, Islam. Since September 11, the paper radicalized and began to publish manifestoes against "Islamic Totalitarianism" with rhetoric similar to George W. Bush’s speeches against "islamo-fascism." But primarily, the paper expresses its commitment to combating extremism by consistently publishing virulent caricatures of Muslims.

Every issue is full of cartoons of hook-nosed Muslim men with long beards, turbans and machine guns, or Muslim men brutalizing women, or in the case of one cover, a depiction of Boko Haram’s sex slaves as welfare queens. Many have criticized the paper as racist, including former staffer Olivier Cyran in an article titled "Charlie Hebdo, not racist? If you say so..." For the paper’s staff, to criticize these cartoons as racist or offensive is to completely miss the point. These are just harmless jokes: "Muslims need to understand that humor has been part of our tradition for centuries," one editorial read.

portraying all Muslims as terrorists is more than a joke: it's a very powerful stereotype that has fueled anti-Muslim hate speech and hate crimes.

I'm a reasonably politically literate French citizen (a dual citizen of France and the United States to be exact), and when in France I used to occasionally buy the paper for its reporting, but eventually stopped because I was sick of having to wade through racist caricatures to get my news. I think the paper has been wrong to characterize its anti-Muslim humor as harmless because portraying all Muslims as terrorists is more than a joke: It's a very powerful stereotype that has fueled anti-Muslim hate speech and hate crimes.

From January to September 2013, 157 Islamophobic crimes were reported in France, an 11% increase compared to the same period in 2012. Women wearing the Muslim veil have been assaulted on the street without the police doing much to find the culprits. And rhetoric about the "Islamization" of France has been given credence by mainstream news magazines such as Valeurs actuelles, which was fined under France’s hate speech laws for a headline that translated to “New barbarians: the foreigners who are pillaging France.” In his book The French Suicide, historian Eric Zemmour pointed the finger at immigration, specifically Muslim immigration, as being the cause of France’s problems.

Racism in France gets a lot of coverage in American media, so I feel I have to insist upon the fact that I'm not alone among the French in thinking that only the three unhinged gunmen are guilty of murdering the Charlie Hebdo staffers and police officers, and that the rest of the Muslim community is just as innocent as all the other individuals who did not participate in the attack. Obviously, anti-Muslim backlash would be misplaced; it does not make sense to blame a group of thousands of people for the actions of a few.

Ironically, conflating Muslims with terrorists is the kind of stereotyping in which that Charlie Hebdo cartoons participated. With that said, while the paper’s provocative rhetoric probably motivated the gunmen, that is a rationale for the killing, not a justification. Nobody should interpret this as arguing that this act of violence was in any way justified. But I stand by my belief that Charlie Hebdo has had a pernicious influence over French politics that's only intensifying in the wake of this tragedy.

America has also recently experienced a terrible event that has been framed and politicized in dangerous ways. On December 20, Ismaaiyl Brinsley killed two NYPD officers, Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos. The lives of the two men were mourned, and justifiably so, because the murder of two human beings is always a terrible crime.

But some public figures blamed the killings on the protests against police brutality. Former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani blamed black activists for creating a "severe, strong anti-police hatred in certain communities." Along the same lines, former New York governor George Pataki described the killings as "a predictable outcome of divisive anti-cop rhetoric of #ericholder & #mayordeblasio."

Sickened by these barbaric acts, which sadly are a predictable outcome of divisive anti-cop rhetoric of #ericholder & #mayordeblasio. #NYPD

— George E. Pataki (@GovernorPataki) December 21, 2014Both men used the actions of a disturbed man who acted alone to smear a movement that expressed legitimate criticism of the police. Mourning the lives of the officers who were killed is not a mandate for total support of the police force as an institution. It is good and human to mourn the lives of murder victims, but this does not invalidate criticism of the NYPD’s abuses and racial profiling. Similarly, the murder of Charlie Hebdo’s staffers should not exempt it from criticism of its racist cartoons and articles.

Just as Brinsley got conflated with peaceful anti-police protestors, specifically black activists, the shooters who killed Charlie Hebdo’s staffers are already being conflated with all Muslims.

I don’t necessarily condemn people for tweeting #JeSuisCharlieHebdo as a gesture of solidarity. I worked for Reporters Without Borders and Freedom House, two organizations that fight for the freedom of speech and the physical safety of journalists around the world, and as such I wholeheartedly agree that the protection of journalists is essential for democracy. But that doesn’t mean I can’t disagree with a journalist, or consider that his or her writings exerts a harmful political influence.

Just as Brinsley got conflated with peaceful anti-police protestors, specifically black activists, the shooters who killed Charlie Hebdo’s staffers are already being conflated with all Muslims. This is especially troubling because pointing fingers at Muslims when Islamist extremists kill white people is as familiar pattern in France as it is in America, as we all remember from the aftermath of 9/11.

1.

Anti-Muslim violence has contributed to making French Muslims feel unsafe in their own country. This is true to varying degrees throughout Europe. Over 18,000 people rallied against Islamization in Dresden this week as well, expressing fears of the growing influence of Muslims even though Muslims only make up about 5% of Germany’s population.

Far-right parties with strong anti-immigrant rhetoric have risen to power and influence all over Europe. It's dangerous to be a Muslim in Europe, and after January 7, it is even more so. Writing about a tragic event soon after it happens often attracts accusations of cynicism and political opportunism, but the real opportunists are the ones who jump on this terrible event to justify their Islamophobia and racism.

Muslim communities have become scapegoats for this killing and experienced intensified violence as misplaced revenge, but we should not let the tendencies to demonize minorities and give in to fear prevail. Free speech does not mean a free pass to spew racism. Peaceful protests do not mean anti-police hatred. These beliefs are not incompatible with the belief that Muslim lives also matter.

Emily Lever is a freelance writer. Follow her on Twitter at @levzofgrass.