The year is 2011 and Macklemore is receiving Seattle Magazine’s 2010 Spotlight Award. For the accompanying cover image, the magazine swathes the Seattle rapper in a dazzlingly white tux paired with matching white shirt, white vest, white bowtie, and white loafers. Surrounding him with equally white trinkets and seating him upon a white swing, the magazine coronates him Mr. Clean, a reference to his inoffensive and polite persona. Macklemore looks conflicted: a rosy face and beige ankles and wrists peek out from this sea of whiteness, but they only exaggerate the photo’s effect. The origin of this conflict is simple: Macklemore is a white rapper, and as the photo inadvertently concedes, his appeal is largely built on that fact.

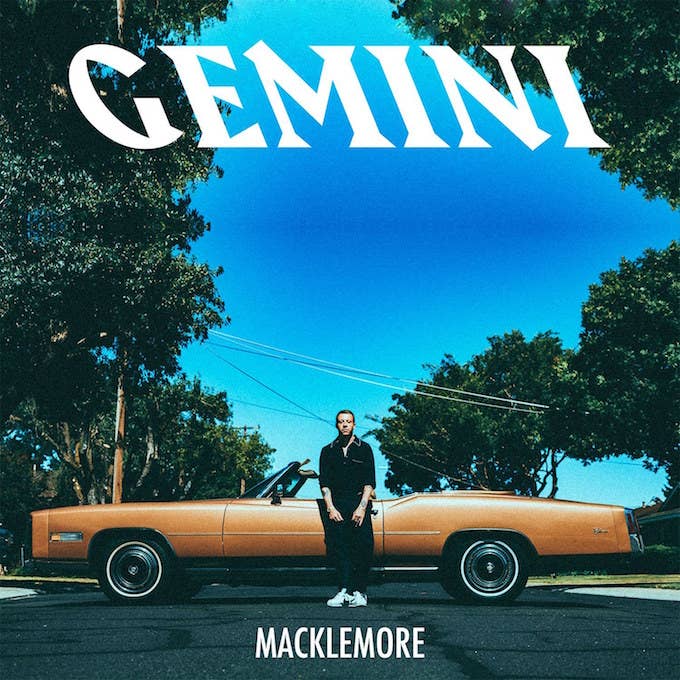

Macklemore has since grown beyond Seattle Magazine, and as he’s risen from local fixture to national act, he’s consistently used his larger platform to complicate his appeal, for better, for worse, and for shame. His last album, This Unruly Mess I’ve Made, seemed to exist solely to confront the fanbase he built off the unexpected success of his 2012 breakout The Heist. Gemini, his second solo album, and third album as a national act, sidelines his struggles with whiteness and offers straight-up pop rap, settling into the white tux. It’s an odd fit.

Tucked beneath the apologia and awkward PSAs, This Unruly Mess I’ve Made essentially laid out Macklemore's core vision of rap. Part Beastie Boys, part Blue Scholars, part Rawkus Records, Macklemore liked his rap goofy, heady, fun, and golden era. Ryan Lewis’ sweeping, ornate compositions gave the record a modern sheen, but Macklemore was ultimately a backpacker. This nostalgia could be grating, but it at least situated Macklemore’s suffocating guilt. Beyond his discomfort with his whiteness, it was clear that he felt an artistic responsibility to the rappers that preceded him and that he rapped because he was so inspired by them. On Gemini, Macklemore follows his peers rather than his idols, and mostly seems lost.

The record is a messy suite of contemporary pop and rap templates that Macklemore struggles to connect to. On lead single “Marmalade” he tries on bubblegum trap, teaming up with Lil Yachty for cutesy, auto-tuned non-sequiturs. The first verse is serviceable, but in the second verse Macklemore does a full-on impression of Yachty’s plodding, carefree flow, and his approach is bizarrely serious, his jokes ironed into a flat deadpan. For “Willy Wonka,” Macklemore recruits Offset for grandiose EDM-trap exuberance, but his rapping is overwrought and labored. Offset casually swaggers through the track and the contrast is jarring. Seattle’s Dave B and Travis Thompson join Macklemore for trumpety joy raps on “Corner Store,” but they utterly dominate the song. Macklemore enlists Riff-Raff-impersonating King Draino on “How to Play the Flute” for a painfully literal rendition of flute rap. Et cetera. Macklemore’s rapping is competent and meticulous, but ultimately there’s an aimlessness to all this sprawl.

The voluntary absence of Ryan Lewis as his main collaborator is the most immediate explanation for all this flailing about. Macklemore recently described their creative approach as intensive, and expressed a need to distance himself from that process to boost his confidence. “I enjoy delving into a concept and really pushing myself to write what is in my heart. But with this album I think there's an air of like ‘first thought, best thought,’ that I don't think that Ryan and I really ever tapped into,” he said. “I think the biggest difference with this is that I wanted to catch a spirit. I didn't want to be doubting myself. I think Ryan is so good at finding what the wants out of people and bringing out the best in people. I think at times it can be daunting a little bit when someone's constantly like, ‘Nope, rewrite it. Nope, rewrite it, rewrite it.’” It’s hard to fathom songs about purchasing mopeds (“Downtown”) and devouring comfort foods (“Let’s Eat”) being too restricting, even alongside lead-footed dispatches about white privilege (“White Privilege II”) and prescription drug addiction (“Kevin”), but even if Macklemore did feel pigeonholed, Gemini does little to liberate him.

Macklemore has always made pop rap, so it’s telling that he conceives of Gemini as his first attempt at it. Early songs like “Thrift Shop” and “Can’t Hold Us” were built to touch the rafters, but worked because of Macklemore’s corny but ingratiating persona. Like his old tourmate Chance, Macklemore’s core appeal is his ability to inject personality into his music. “I have always been somebody writes who from a conceptual place, from a personal place,” he once said succinctly. On Gemini Macklemore conflates humor with personality and flattens one of his sole endearing traits. “I pull up in that purple thing, dressed like Prince in Purple Rain, he raps blandly on “Levitate.” “My grandma smiling down on me like woo, that boy got bars,” he says on “Glorious.” Macklemore has always traded in winking self-deprecation, but in the absence of politics or polemics, jokes become his only currency and we’re left with song after song of filler. It’s easy to see through the act.

When he isn’t hopscotching across modern pop trends, he opts for the same lush, panoramic soundscapes that he preferred from Ryan Lewis and it becomes clear why those initially fit him. His most inspired performances come when he revisits guilt on “Intentions” and waxes nostalgic alongside Kesha on “Good Old Days,” slowing his cadence to that signature spoken word murmur. “Wish I didn’t worry about what other people thought and felt comfortable with myself,” he plainly says on “Good Old Days.” “Miracle,” which follows an interpolation of Goodie Mob’s “Serenity Prayer,” features some of his sparsest, most impactful writing. It’s one of the few songs in his catalog where he doesn’t heavily lean on signifiers, and you can feel the anxiety as he dances around the specter of relapse. (Dan Caplan’s Frank Ocean impression is nothing like the real thing, but the song at least feels lived-in.)

Macklemore’s dilemma makes sense—very quickly he went from local legend to overnight sensation to clown prince of white guilt, and he wants to shake that impression because he always meant well (“Intentions”)—but his solution elides what caused it. His decisions were the common denominator in his own tarnished reputation, not himself. He apologized for robbing Kendrick of a Grammy, then publicized that apology while keeping the award. He named a song after white privilege, then rapped about his experience at a Black Lives Matter rally. He accused hip-hop of homophobia on the same song he declared his heterosexuality. Gemini resolves all this conflict by resigning Macklemore, the human controversy, and replacing him with Mr. Clean, the hitmaker. As always, he’s missed the point.