Lance Stephenson is the voice of reason on this basketball court. He’s back in Coney Island, swinging by the beachside court on 27th St. and Surf Ave. where he honed his game, and a crowd of midday preteens are handling the surprise visit by swarming him familiarly, like a rich uncle at Christmas. Stephenson’s said hello to a trio of ladies pushing a baby stroller between them who ask if he remembers them (“Of course”), and the kids who’d been playing knockout under the basket follow him in a tight halo.

On the edges of the crowd, though, a roundish kid has found the NBA star’s 8-year-old brother Lantz and is talking shit in his ear, low enough that no one notices until the fat kid tries to bulldoze Lantz with a chest bump. Lil bully can’t be more than 10 but he’s taller than Lantz and Lantz is easy to spot in a Burberry polo, so he keeps coming at the younger Stephenson until big brother shoots a glare and calls for his dad (also Lance) to see what’s up. That’s all before one of the other two dozen or so kids pipes up about the bold-ass big boy: “He does crazy stuff like that all the time; he’s off,” by way of explanation. Some of the other gathered young ones nod in affirmation, but all turn their attention back to the guy with the ball and the glow of money, as if the appearance of both the weirdo bully and the NBA player nicknamed Born Ready are both common sights around here.

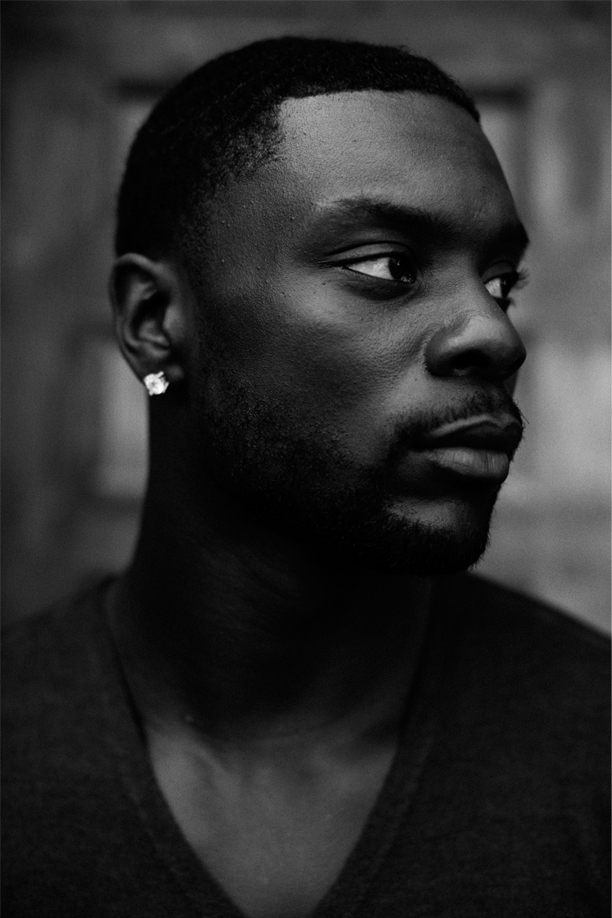

To the casual NBA fan, the name Lance Stephenson probably does not conjure the phrase “voice of reason.” The on-court highlight the fourth-year guard is now most famous for happened this past May when Stephenson, with his Indiana Pacers down 3-1 in the Eastern Conference Finals to the Miami Heat, blew in LeBron James’ ear during a break in play. That act spawned about a billion Twitter and Instagram memes (blowing out birthday candles, on video game cartridges, etc., etc.), and two months later Drake recreated the moment at the ESPYs, an event Stephenson had never been invited to prior to that incident.

Because their teams were rivals and because it was the playoffs and because the player Stephenson fucked with is the best in the world, the spontaneous act of needling got magnified and re-aired throughout the rest of the summer. And it was reason enough, along with the fact that Stephenson was playing for a bigger contract, to bring up all the other miscalculated bits of gamesmanship he’s employed through the years that, depending on how many times you’ve ever uttered the phrase “plays the game the right way,” could’ve been construed as bush-league stunts.

Stephenson got tossed from a March game for yelling “WHAT!” at Dwyane Wade after he swerved around two defenders and rammed in an angling layup to put his squad up in the fourth quarter. In Game 2 of the Conference Finals he’d flopped so grandly after contact with LeBron that he laid out on the court, peeking at the refs’ reaction, a good minute after the whistle (he was fined $5000). During the infamous ear-blowing Game 5, Stephenson also ambled into the Heat huddle in the third quarter (with his team up 5), an act that had Jeff Van Gundy offering that he’d have no problem with one of his players “physically accosting him” for doing so. Stephenson came back in Game 6 and tapped James’ jaw, literally this time. All of which recalled the time he made a choking gesture at LeBron from the bench as King James bricked a free throw at the end of Game 2 of the EC Semis in 2012. For all these Indiana sins—in the moment, against a rival who’s owned his team, in support of a Pacer team that goes bewilderingly soft against the Heat—Lance Stephenson has been made to apologize for his impropriety, his failure to defer.

On the streets of Indianapolis, and obviously here in Coney Island, Stephenson got fistbumps and laughs and hugs for his trolling because those who’ve watched his climb from bench-riding second rounder to LeBron stopper (or at least LeBron speed bump) respect that he made that progression thanks to his refusal to back down to anyone. He’s said all the right things in the media since it happened, but in Brooklyn, at least, Stephenson doesn’t have to be contrite, because when the counter guy at his favorite deli saw him walk in for the first time this summer, they laughed about it. In a neighborhood where all eyes have been trained on him since way back, they’ve taken in a more complete view of what it’s taken for Stephenson to get out and how much he must love them to come back.

The NBA’s gen pop viewer, maybe not surprisingly, took the narrow view on Stephenson by focusing on the one incident that made it to more media outlets than any other highlight he’s ever had. But to at least two team execs who happen to have been all-time greats, the Game 5 antics just underscored how effective Stephenson had been at haranguing LeBron into an all-time worst playoff performance (seven points, five fouls). When Larry Bird couldn’t max Stephenson out (Indiana offered five years at $44 million), Charlotte owner Michael Jordan wooed Stephenson over dinner in Las Vegas this July with a comparable but shorter deal (three-year, $27 mil) and also tipped his hat, letting the free agent know that he recognized some of himself in Stephenson’s refusal to watch the throne.

“Jordan said he did stuff worse than that on the court,” Stephenson says. “He said he dunked on Patrick Ewing and after he wanted to hang on the rim and try to hit him with his leg, on purpose, while he was hanging on the rim. I think that’s way worse than blowing in somebody’s ear.” That summertime dealing has left Indiana missing both Stephenson’s scoring and edge now that Paul George is out and ensured that Charlotte has a player with the balls to prevent LeBron from making playoff statement dunks directed at MJ.

The two teams’ pre- and post-Lance fates are a reminder that perspective has always determined how people value his game. If we’re keeping it 100 the difference between the choke gesture being out of line in 2012 and the ear blowing being funny in 2014 is that the first taunt came from a bench reserve (not, say, Reggie Miller) and the second came from an emerging star. By this year’s ECF Stephenson was the league’s leader in triple-doubles and, for a good part of the postseason, the only Indy player unafraid to try anything to stop Miami, a team that Pacers coach Frank Vogel later said deserved to be mentioned in the same breath as the ‘90s Bulls. (Really tho?)

So even though Stephenson cried when Indiana lowballed him on his contract and he realized that his run with his first NBA team was over, Charlotte is looking like a better fit for his second act. In Indianapolis, Stephenson took advantage when teammates got injured or traded, went game-speed in practices until he wrested a starter’s spot, and became a player Larry Bird and LeBron James and Michael Jordan and even you have to take seriously. As a Hornet, he’ll be the wing-scorer and defender that the team sorely lacked when it got swept by the Heat in the first round last season. As the big free agent “get” Stephenson has a shot at being the leader who pushes a playoff team further into contention, rather than just being a third star with a knack for disruption. “I want everybody to respect my game: a tough, competitive player that always wants to win and never backs down to anyone.” Which is what sets Lance Stephenson apart from other cross-branding, emergent superstars who want to be respected for everything else.

There are actually four Lance Stephensons. Lance’s grandfather was the first, a Vietnam vet who suffered from exposure to Agent Orange and alcoholism, and who, when he returned to Brooklyn, was known around the neighborhood for being, well, a little off. The name chain of Lances (Stephenson’s dad, also Lance, known as Stretch, begat Lance and Lantz) was an intentional act of rebranding. Each heir was supposed to give the grandfather’s name a different resonance.

In Coney Island, they have. Outside of Brooklyn, Lance III’s hoops lineage is well known to fans who’ve followed any one of a dozen point gods out of the area, or even watched He Got Game. Stephenson went to Lincoln High, same as Steph Marbury, same as Sebastian Telfair, same as Jesus Shuttlesworth. On the court, in Brooklyn, Stephenson outpaced them all—he was the winningest New York high school player of the group, which meant just about what you’d expect. He had a reality show through much of his senior year, eligibility issues and the accompanying recruitment drama that dissuaded most big-time schools from attempting to sign him.

After putting in a year of work at Cincinnati, where he won Big East Rookie of the Year, Stephenson dropped his name into the 2010 NBA Draft and watched his hometown New York Knicks pass on him twice before the Pacers selected him at the 40th spot. So Stretch and the entire family, plus a few neighborhood friends, moved out to Indiana, splitting a two-story suburban house and trying to make Indianapolis seem as much like Brooklyn as possible. His mom Bernadette supplied the home cooking, Stretch handled his day-to-day management, and his best friends Aaron and Biggs hung around for laughs (this year, Biggs helped come up with and then shot the videos of “Sir Lancelot” clowning for an All-Star spot). With a logjam on the Pacer roster at both guard spots when he first arrived, Lance’s only shot at getting playing time was if he turned the practice court into his own private BK blacktop. He went hard in every practice from Day 1 until his last in Indiana (which Evan Turner learned this year), thinking he was proving himself to the organization the only way he knew how.

That’s when he first got word to fall back. Clark Kellogg, the player development coach on staff, pulled Stretch aside to ask him to tell his son to chill after post-practice one-on-ones against then-starting point guard T.J. Ford got a little too real. “He would tell me, ‘Hey, Lance is working extremely hard, but there's a time to play hard and there's a time like hour before the game and Lance should not be going hard,” the elder Stephenson recalls. “I'm like, ‘For real?’ Okay, I'll have to tell him that.’ So it was an adjustment for me, for him, for everybody knowing when to pick your spots. That's the main thing about being a pro, you gotta know when to be a pro. And I think that being with the Pacers that really came out and that was the lesson that he learned, if anything in his first four years in the NBA: Be patient and know when to go and when to be yourself.”

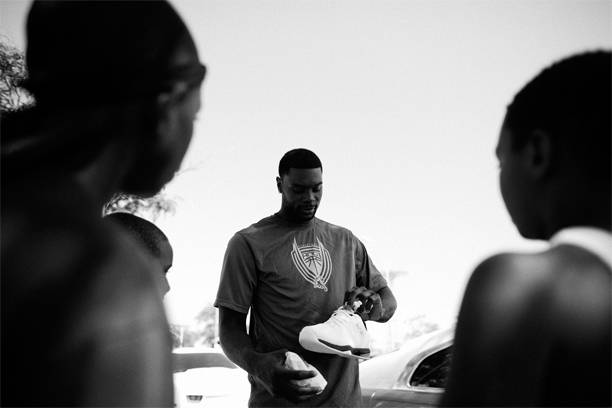

The call was the polar opposite of everything any of the Stephensons learned back in Brooklyn. Stephenson earned the “Born Ready” nickname in parks like the one at 27th and Surf by going at older, bigger players as soon as his grandma let him cross the street by himself. By the time he was 11 he was almost six feet tall and he didn’t have to beg to join in anymore. From there he learned to wrap the ball around other guys’ backs, laugh at—but never call—hard fouls, to go for the jugular when the moment came. And to burrow under opponents’ skin if it would throw them off. “Just getting in somebody’s head—in streetball that’s probably like 50 percent of the game.”

If that self-reliance, that premium on staying alert and working all the angles, was being taught on courts around the country, then youth leagues wouldn’t be giving trophies to kids just for showing up, and NBA coaches wouldn’t be trying to figure out how to teach the No. 1 draft pick to be aggressive. Despite having financed and run an AAU team in Indy for Lantz, Stretch still brings his youngest back to Brooklyn in the summer, to get pushed and bullied, and to figure out how to finish without getting bailed out.

For most of that infamous Game 5, Stephenson blended that Brooklyn message with his Indy lessons on pacing, if anyone cared to notice. Midway through the first quarter he steered LeBron deep into the lane, elbowed room for a spin move and then dropped a pillow-soft lefty lay in; right before the half, with Miami trying to pull away, he hit Ray Allen with an in-and-out and wove around two help defenders to get to the rim. Stephenson put up 12, 5 and 5 (with two steals), prodding the D with both deftness and fury as the situation called for it, until Paul George finally showed up in the 4th quarter. They took turns hounding LeBron on defense, drawing offensive fouls and holding the King to seven points all game, following the dictate Vogel had given beforehand to “make him smell your breath.” In the midst of that performance trying to keep from being eliminated, is it any wonder that those who knew him best shrugged off what happened next? “I didn’t even notice it until they put it up on the scoreboard,” Biggs remembers. “And we fell out laughing. It was such a Lance thing to do.”

Given the ubiquity of the replays on TV though it’s easy to imagine how another player might’ve capitalized on it differently. “The fans embraced it. Every time I go somewhere they’re like, “Can I blow in your ear for the picture?” Stephenson says. “Some of the publicity is good and some isn’t. I could probably get a Winterfresh endorsement because I blew in LeBron’s ear but I think it hurt me more than it helped me, definitely with picking teams and teams trusting me not to bring that type of publicity to the team.”

Instead of embracing the loveable villain role, Stephenson shut down any more convos about “the incident” until after his contract was settled. Running away from becoming a pop culture meme? That’s not been the blueprint for the league’s youngest stars lately. Stephenson was right on schedule for a rebranded nickname a la Paul George (Young Trece?), a celebrity girlfriend (see: Swaggy P), or an attempt at speaking couture (hi Russy). Stephenson’s birthday falls squarely in the midst of New York Fashion Week, a time when most budding NBA stars are testing their fashion bonafides, trying to get close to Anna Wintour. Proximity to such name-breaking affairs is why free agents are perpetually angling to become New Yorkers or Los Angelenos.

But instead of cashing in on his crossover appeal by booking a room at an iron-and-glass Tribeca hotel or sidling up to models and corporate sponsors, Stephenson posted up all summer at the Marriott in downtown Brooklyn, and took four days off to celebrate his born day with his lifelong friends by, among other things, copping himself a car and a ridiculously heavy Cuban Link chain. Then he went back to working out with Jamel Thomas, the Marbury cousin and former pro who’s trained every prep talent out of Coney Island since the nineties. It was the most timelessly New York summer possible and it took a battle-tested New Yorker to pull it off while most of the Knicks and Nets were at movie premieres or fashion parties.

In fact, Stephenson was more than an hour late for the neighborhood tour that lead us to the court where fatty raised up on his kid brother, because he stopped to cop his female companion an outfit—at the Sneaker Town on Mermaid Ave., around the corner from his boyhood home, so she could come run the Coney Island sand dunes with him afterward. And yep, the duo hopped out of the Rolls Royce Wraith he’d bought about a week prior, the same whip that Stephenson references on his remix of the ultimate New York summer anthem, Bobby Shmurda’s “Hot N---a”, which, he’ll proudly tell you in person and on the video (shot in Coney Island, obvs), “Went to number two on datpiff.com.”

Stephenson says he finished the remix in just twelve takes in his first ever attempt at recording professionally, mostly because he didn’t have to make anything up to fill the bars. Just copped the Wraith? Him and Kemba in the backcourt making dead meat of fools? Watching AI drop 40 with the french braids? #AllFacts. In the middle of the best summer of Stephenson’s career so far, he managed to one-up the original song’s infectious bluster with slick-talking veracity. Is there anything more New York than that?

Instead of riding the publicity wave, Stephenson banked that the mettle that Brooklyn imbued him with would ultimately pay off, and this summer proved him right. Beyond the Charlotte deal which should set him up for bigger paydays, sooner than Indiana could offer, And1 has made Stephenson the face of their relaunched brand in the hopes that some of that unrelenting image will rub off on their reissues. “He represents the athletes on the court or playground that never give up, never give in,” says And1 senior VP Cape Capener. “We feel he will quickly become the engine of the entire Charlotte Hornets franchise. He will be an NBA All-Star in 2015, where by the way, the game is being hosted in Brooklyn and New York City. We couldn't have scripted the story better.”

Two weeks after we all left the Surf Ave. court, the Stephenson entourage hit I-95 south in a pack that included the Wraith, Lance’s buddies in his flat white Camaro, and his parents in their Explorer, ready to bring Brooklyn to Charlotte. The idea that he could come back to the borough as an All-Star is a boast that, like Stephenson’s game, seems more and more reasonable every passing day.