It’s a coincidence, of course, that between them Chris Paul and Carmelo Anthony have gotten a total of 23 signature shoes from Jordan Brand—10 for Paul, 13 for Anthony, whose signature line has reportedly been discontinued. If that number seems incredibly high, it’s probably because hardly any of those shoes, save perhaps Melo’s early hybrid retro Jordan models, have been memorable. And with Russell Westbrook becoming the latest to receive a Jordan signature on-court shoe, maybe it’s time to finally ask why this is something they keep doing? Jordan signature lines need to end.

This isn’t Westbrook’s first signature shoe with Jordan—he’s had two off-court models—but after a period of him being the primary guy behind the flagship Air Jordan, the awkwardly named Why Not Zero.1 is his first on-court model. It’s easy to tell why Jordan would do it: Westbrook is the brand’s most compelling player, the defending MVP whose explosive exploits are all over media, both TV and social. Giving him a $120 signature model puts him on the same plane as guys like Steph Curry, Kyrie Irving, and Dame Lillard. Westbrook has also been spotty on wearing the latest Air Jordan, returning again and again to earlier models that he seems to prefer. A further thought, perhaps, is that the latest Air Jordan can sell itself. But, 15 years after Michael Jordan’s last retirement, and at $185, it’s a tougher sell than ever.

In the beginning, Jordan Brand’s signature shoe model made sense. It was tiered. Jordan gave signatures first to Vin Baker and Eddie Jones, young up-and-comers who filled two different lanes—quick and strong—that took the do-everything Air Jordan and broke it into two, less expensive models, one for guards and one for big men. The brand also gave signature shoes to Randy Moss and Roy Jones and Derek Jeter, athletes in different sports who (at least theoretically) represented their sports the same way Jordan did his.

This worked, at least for a while. Now it doesn’t. Maybe it’s Jordan who they moved away from what WAS working—signature models for athletes in other sports and those not quite good enough to wear the flagship shoe—and started doing what everyone else was doing, which was giving signature models to their top endorsers. For every other brand this made perfect sense. For Jordan, not so much.

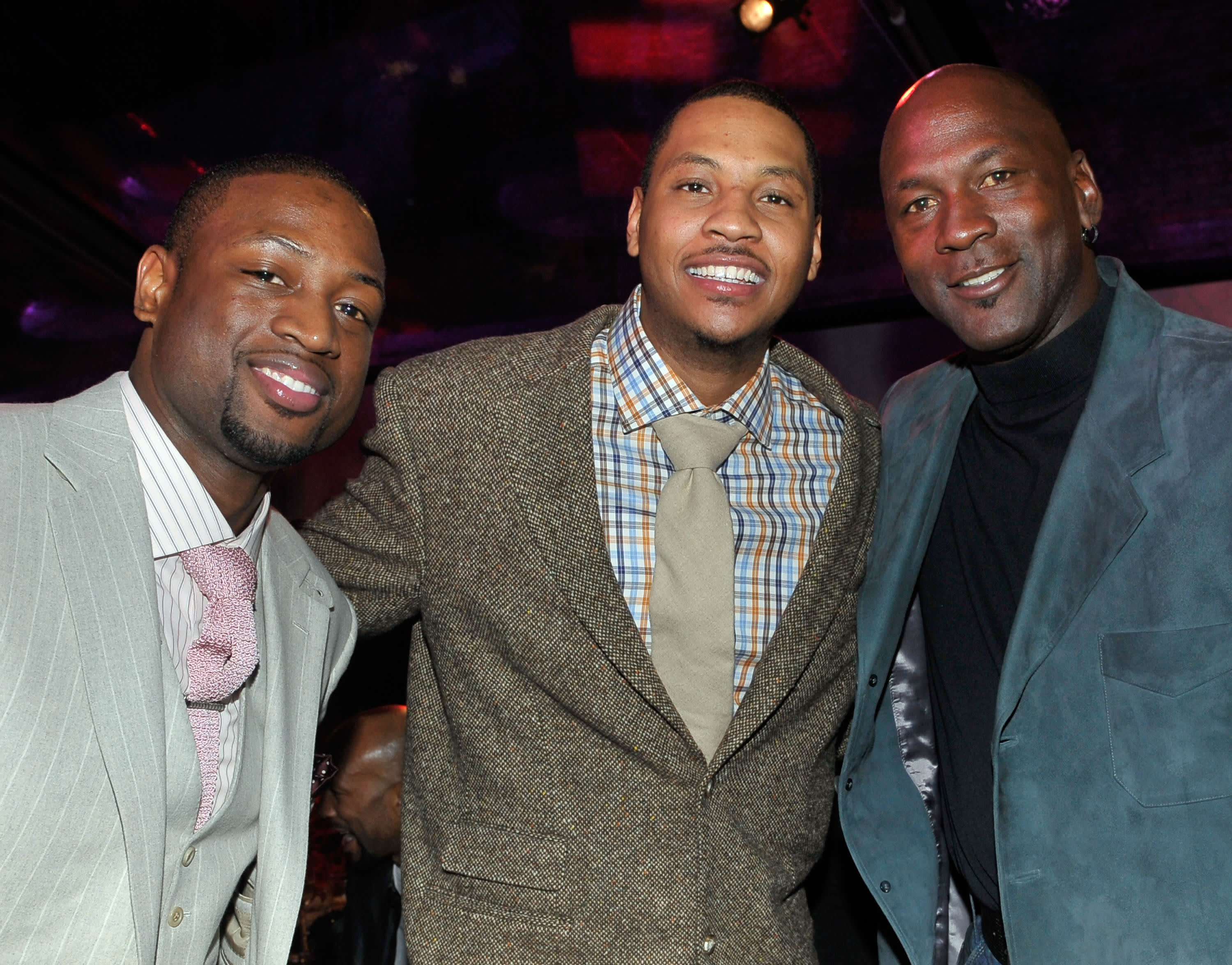

Paul and Anthony are just the most recent examples of this. Take it back to Dwyane Wade, who signed on as a Chicago-born and -bred successor to the company’s namesake. Wade joined Jordan from Converse as the flagbearer for the flagship Air Jordan model—he’d had signature models on Converse, but signing with Jordan in and of itself was widely seen as a step up. He was placed on equal footing with Jordan himself as the face of the Air Jordan 2010. This made sense. Jordan had retired, and Wade was a similar player, a physical guard with championship credentials who young consumers could identify with. He’d bring the entire Jordan Brand into the future.

That didn’t last long. The very next year Wade got a signature shoe of his own, the Fly Wade, a takedown of sorts that no one much cared about. One blah sequel later and Wade himself was gone, off to helm his own namesake brand through Li-Ning. He spoke of legacy and following in Jordan’s own footsteps as reasons for leaving, and no doubt he got offered generational money, but it’s easy to think things could have gone differently had his signature models mattered—or had he stayed the face of the entire Jordan brand.

Here’s the question I can’t answer when it comes to Wade and now Westbrook: If the Jordan Brand’s top basketball endorser wears something other than the actual Air Jordan, who the heck is the Air Jordan even for? Yes, it’s technically still for Michael Jordan himself. But Mike is 54 now, and “I want to be like Mike” is just a lyric from a commercial jingle. Kids today want to be like Russ, and if that’s the case, they should want to wear what he’s wearing. Which should be the flagship Air Jordan.

That is, assuming kids care what an athlete wears on court at all. We’ve reached the point where as much, if not more, attention is paid to what an athlete wears TO the game. It’s more notable when LeBron James wears, say, Round Two owner Sean Wotherspoon’s Air Max 97/1 hybrid than the latest PE of his LeBron XV. The former is a choice, the latter is an obligation. And the sneaker leaders today are people like Wotherspoon himself, or Kanye West or Virgil Abloh. Instagram is the new SLAM magazine, off-court is the new on-court. At some point it’s worth asking whether signature basketball models are worth it at all anymore.

Jordan Brand is in a unique position in basketball footwear as the brand itself was birthed from a signature model and still wears the name (and silhouette) of a player from recent memory. Its approach to how it works with athletes should be unique as well. In a way it is—athletes who sign to Jordan aren’t just randos getting sneaker deals, they are vetted by Jordan himself as to whether they fit the mold of a “Jordan athlete.” Many of them, including Paul and Westbrook, were Nike athletes before they became Jordan athletes. Like Wade’s move from Converse, this was widely viewed as a step up. So why have Jordan signature sneakers at all? If the Air Jordan itself—now in its 32nd iteration—is seen as the pinnacle of basketball footwear, designed for the greatest ever, why would anyone on Jordan want to wear anything else?

What’s ironic about all this is that Jordan is facing a problem that its namesake himself started. Once Jordan received the Air Jordan from Nike, signature shoes slowly spread through the All-Star ranks. Now, 30 years later, they’re seen as more of a right than a privilege, just another stepping stone on the way to stardom along with All-Star appearances, national team selections, and max contracts. Chinese brands who don’t even sell products in America have used the enticements of a signature model (and the vast Chinese market) to sign countless NBA players. Evan Turner is on his fourth signature model with Li-Ning.

Just as Michael Jordan changed the way sneakers were marketed in the mid-’80s, Jordan Brand could change things now: Stick to designing the best possible sneakers for the best athletes in the world, and pick those who are willing to wear them. And by all means take their input into consideration: Let them test it, design it around them, give them all the PEs they want. The best deserve the best. But signature shoes? The Air Jordan already is one. For the top-tier Jordan athletes, just wearing that should be honor enough.