Think about your workplace: office, restaurant, retail store, circus, recently-pivoted-to-video media company, anything. Now imagine your boss brings in someone to do a job almost identical to yours, who you have to work side-by-side with. Somehow, they start taking a cut of your paycheck—they're not technically allowed to do that, of course, but management always turns a blind eye. And the person who was hired for the you-replacing job, which has a more respectable title than yours despite nearly identical duties (and who looks down on you as a result), has to have a particular skin color—probably different from your own. If you complain about anything, your hours get cut or you’re fired.

This is the exact position in which dancers at many NYC gentlemen’s clubs now find themselves. For about the past five years, clubs in New York City have been bringing in bartenders who perform almost all of the same functions as dancers—while dressed identically—and frequently collecting tips intended for the dancers in the process.

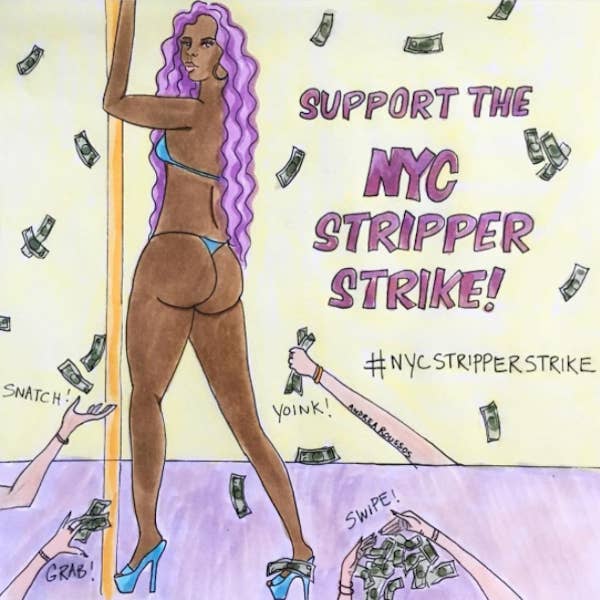

But some of the dancers are getting fed up, and are organizing to fight back. A movement known as NYC Stripper Strike sprung up late last month out of social media conversations among women dancing at clubs in the city. They discovered they shared many major concerns, and decided to band together.

Gizelle Marie, a veteran dancer, has a popular Instagram account. One day last month, she was talking to another dancer via Snapchat. The woman was venting about issues at her club, and reposted another woman who had similar complaints.

“The girl that she reposted, she basically was telling me that she was tired of everything,” Gizelle tells me when I reach her on the phone. “I feel like we all are tired, but people are not saying anything. So I took it upon myself to post on Instagram, because my Instagram has a bigger profile as far as followers. When I posted, other girls started speaking up about the same issues.”

The two issues that most of the dancers rallied around were the way the clubs give favored treatment to bartenders over dancers and a related problem, discrimination based on skin color.

In many gentlemen’s clubs, particularly in Brooklyn and Queens, the last five years or so have seen a sea change in the role of bartenders. Gizelle attributes the origin to a group called Startenders.

“These women were actual models,” she explains. “So these women had a lot of structure and a lot of poise, [and] they knew how to conduct themselves. They were taught how to be bartenders, and not dancers that do bartending as well.”

The idea of using models as bartenders caught on, and soon tons of clubs were hiring attractive women, often dressed identically to the dancers they were working next to, to pour drinks. “It’s become a confusion between the dancer and the bartender,” Gizelle says. “[Customers] can’t differentiate between the two.”

The new bartenders, who Gizelle notes are almost uniformly light-skinned, are frequently unlicensed and are often fined for being short on the register or other offenses.

Panama Pink, another dancer involved in the NYC Stripper Strike movement since its earliest stages, says that the bartenders nearly always do a poor job, while simultaneously looking down on their co-workers.

“I’ve seen a lot of my customers, my friends, or just people in general, even the promoters, the managers, everybody—I’ve heard everybody complain. The girls are on Snapchat and on their phones all day, they barely listen to the customers,” she tells me. “They’re not experienced mixologists; a [low] percentage of them know how to actually make drinks or are licensed, period. They just know how to pour shots from bottles, and they’re pretty much strippers, but don’t wanna be called strippers.”

Bartenders can’t get hired in the first place without a certain number of Instagram followers. This mirrors wider trends in the entertainment industry as a whole.

Satori Ananda, co-founder of the social media strategy company SocialWerk, explains that, if you’re an aspiring musician, “right now labels won’t even talk to you unless you have a 10,000 [person] solid fan base,” which translates into about 100,000 followers on social media. She says that the same logic applies to dancers in the clubs of her native Dallas.

“I know a bunch of dancers here,” she says. “It’s the same thing. They’re all Insta-models. All of them. So what happens is, if they say that they’re at the club, that brings business in. They’re marketing influencers. And wouldn’t you rather have a girl that has a following that’s coming to see her because she’s been showing off online all day than a girl that you just hired off the street that doesn’t really bring any value except to people who are coming in? They’re bringing in their own customer base. I think that’s pretty much standard across the entertainment industry right now.”

Sinnamon Love, a former porn actress and director who is a member of the AVN Hall of Fame, and who has transitioned into a career as a writer, radio personality, entrepreneur, and educator, has seen this pressure to gain followers on social media affect the entire sex industry. What that does, she says, is severely disadvantage women who don’t want to make the business their entire career—as she puts it, people in the “stereotypical ‘stripping my way through college’” situation.

“It makes it more difficult for women who want to do this type of work as a means to an end, as opposed to the end itself,” she says. “As we all know, once those images of yourself are out there on social media, it makes it very challenging to take that back.”

M. Marie, the owner of the dance studio Poletic Justice that hosted the initial NYC Stripper Strike meeting, has been dancing for over a decade. To her, having bartenders dressed like the dancers is “a very misogynistic type of approach to take.” She blames club owners and promoters who “lead with their penises before anything else.”

“It's like: Are we a gentleman's club? Are we a bar?” she asks rhetorically. “Are we a regular bar, with bartenders, or are the dancers like go-go dancers, and we're just here to entertain the people, but the bartenders are the main attraction? You're allowing bartenders to swipe money off of your stage, or distract the customers from paying the strippers for the entertainment; that's literally taking away a person's salary.”

That last part, about swiping money off the stage, adds insult to injury to the women dancing. Bartenders have been caught on video sweeping money intended for the dancers off the stage and onto their pile of money on the floor below. M. Marie explains how it works:

“I have to literally stop my show just so I can get to the ground fast enough so that my money don't end up in the bar pile,” she tells me. “Once it gets down to the ground, I'm not allowed to go to the floor and get my money, 'cause it's mixed in with theirs. And they do that purposely, so that when people are throwing [money], it gets mixed up. We don't have the right, as an entertainer, to go down and get the money that's rightfully ours. But they're able to swipe money off our stage and distract customers from paying attention to the entertainers.”

Having the bartenders dressed like dancers, as you might imagine, also cuts into the amount of money customers spend on the women onstage. This particularly stings because the dancers pay the club what are known in the trade as “house fees” (M. Marie pins the number at $165 a night, in her experience), simply in order to be allowed to work. Susan Elizabeth Shepard, an expert on strip club-related labor issues and a former writer at the sex worker blog Tits and Sass, compares house fees to the money a nail tech or hairstylist will pay to a salon in order to have a place to work.

“Bartenders are doing our work, as well,” Gizelle explains. “They're behind the bars dancing. Okay, if you wanna do that, that's fine. But why are they not paying a house fee? They're doing the same job that we're paying to do. What's the whole point of us being there? They might as well just take the poles out of the club.”

Inseparable from the difficulties with bartenders is the issue of colorism. Among dancers, there is near-universal agreement that dark-skinned women cannot get hired as bartenders, and often miss out on other opportunities as well (Panama, for her part, has plenty of stories of dark-skinned women not allowed to work in VIP areas, and of being told not to bother showing up to work on specific nights). For Sinnamon, this is another chapter in a long story of discrimination in the sex industry—a story that is written by the (mostly) men who own film studios, strip clubs, and the like,who are forcing their idea of attractiveness onto their clients. She tackled colorism in sex work in an essay found in the 2013 anthology The Feminist Porn Book: The Politics of Producing Pleasure.

“In the early to mid-'90s, video vixens pretty much had to pass a paper bag test,” she remembers. “You would see all of the women had a very similar look to them; they were all fairly fair-skinned, curly hair, very petite, yet curvy figures. The image of women of color in porn is very built around these white, male company owner fantasies of what makes black or Latin or Asian women attractive. Much of that is because of their consumer base—at that time, at least—was primarily white men. They're producing and distributing porn for white male consumption, because that's their consumer base.

“When it comes down to sex work in general, there's no market research,” she continues. “There's not a Nielsen of the sex industry going around and asking men, ‘What do you find sexy and attractive?’ There’s this misconception of beauty that gets carried over into these sex work-related labor practices. So when I read that darker-skinned strippers are not being allowed into VIP rooms or not being allowed on stage when there are celebrities there, you have to come to the core of why that is: For whatever reason, those owners or those managers have this idea that the men who have all this money would not be interested in those women. So you have to think about the psychology of sex and why they would possibly think that these black men might not be interested in a dark-skinned black woman. It's because they personally don't think that that's attractive. So it goes beyond the work itself and what the standard of beauty is that's being pushed on our society at large and our community at large.”

But even beyond wanting a change in societal beauty standards, what women like Gizelle and Panama want is respect—”to be respected equally,” in M. Marie’s words. And the early steps towards gaining that respect took place during the initial meeting of NYC Stripper Strike.

The gathering, by Gizelle’s estimate, had 20-30 people—mostly dancers, but also customers, bouncers, ex-bartenders, and even the odd informant from the club owners’ side. The whole experience, says M. Marie, was “empowering.” The meeting mostly consisted of women sharing stories and realizing they had similar problems. Now comes the hard work of creating solutions, while dodging retaliation from club owners.

While the group is branding their movement with the phrase “NYC Stripper Strike,” a widespread work stoppage is not on the table—at least not yet.

“It's not something that's gonna happen right away,” Gizelle says. “We did the meeting not because we wanna go on strike right away; we just wanted to see who would start a movement.”

Panama, who has been extremely active in the movement, mostly works outside of New York City, so she feels like she can afford to go up against owners and management. Gizelle says she’s faced backlash (including being banned from many clubs), but freely admits that “dark-skinned women tend to get it the worst.”

And if the talk of “owners” and “management” sounds familiar, it’s because, tacky headlines aside, this is at heart a labor dispute. And, like many workers in the ever-growing gig economy, strippers are independent contractors, not employees. Thus, they effectively lack the means to protect themselves from discrimination or firing, for any cause—and don’t even begin to think about workers’ comp for a very physically demanding job where injuries are common.

Shepherd sees this lack of rights as perhaps the biggest issue affecting dancers—and the rest of us. She ultimately views the answer as expanding the rights of contractors across the board.

“The solution would be to extend rights and services to all workers, regardless of status, because everybody is gonna be an independent contractor soon enough,” she says. “We should ensure better treatment for workers, regardless of their classification.”

The women of NYC Stripper Strike have big plans that extend beyond fixing the bartender/dancer dynamic. For Panama, the movement is a chance to share information about finances, and about ways to make money once dancing is no longer an option.

“What we plan to do from all this is build a stronger bond between women,” she explains. “We wanna have outlets for women, and teach women what to do in life when you get older. Things that you need to know how to do, life skills. A lot of things that women in the strip club industry just lack because they don’t even know that there’s more to stripping.

“A lot of women don’t know that being a stripper, you’re an independent contractor and you can pay taxes. You can file taxes. If you have a kid, you can be on the books, if you wanted to, as you work. You have rights. If you wanna go back to school, if you’re trying to get back into work, there’s resources that some of us know of, people that we know, to help women get on the right path. Because at the end of the day, this isn’t forever.”

Gizelle and her compatriots are very clear that, whatever the larger economic implications of their struggle, they are first and foremost fighting for each other.

“This is our time to fix the problem,” she concludes. “There's so many things that go on in the club, it makes the woman so discouraged, and she just wants to give up. The whole world is literally watching what's going on in New York now. [People are] like, ‘Oh, why did you put it out there?’ But it's been put out there. It's just somebody had to speak out and complain, and that was me.”

Panama has plenty of people around her wondering why she’s taking part. For her, there was never a question.

“I got that a lot—why am I saying something? Why am I standing up for people? If I haven’t been working in New York; if I’m not having trouble making money; if I’m not dark-skinned; if I’m not this; if I’m not that—why am I saying something? Because it’s not right. Because that’s what people do. That’s what humans do.”