In 1989, Camella Ehlke was a 19-year-old art school dropout with a passion for sewing who launched her pioneering streetwear label, Triple 5 Soul, out of a storefront apartment on Ludlow Street in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Triple 5 Soul’s tie hats and piecework hoodies quickly garnered the attention of rappers like Pos of De La Soul, appeared in trendy magazines like Paper, and had fashion-forward customers from Japan filling their suitcases with the brand’s wares. Ehlke’s store became a hub for Downtown New York’s creatives in the ’90s and Triple 5 Soul represented the energy emanating from the Downtown New York club scene. By 1996, Triple 5 Soul grew to become one of New York City’s first major streetwear powerhouses, opening stores in Los Angeles, London, and Japan.

“Honestly, I don’t know how I did it. But I definitely winged it and it was a hustle,” Ehlke tells Complex from her studio in Brooklyn. “I honestly got lucky by partnering with someone, even if he did eventually turn out to be a toxic human being. We make these deals with the devil and it became 80% business and 20% creativity.”

After entering into a partnership that compromised Triple 5 Soul’s creativity in favor of commercial profits, Ehlke decided to leave the brand in 2004. Like many other streetwear brands of the ’90s, Triple 5 Soul eventually died out. But in January, the brand’s Instagram made a surprising post revealing that Ehlke would make her return to streetwear as Triple 5 Soul’s creative director again.

“My main purpose to come back with the brand really sparked during COVID when I was sewing and making a lot of stuff,” says Ehlke. “I was talking a bunch to Virgil Abloh about it and he just said, ‘You gotta get on your sewing machine again. You gotta start telling these stories and let the youth know about the legacy and history of this brand, because it’s really important.’”

Complex had the privilege and pleasure to speak with Ehlke about what Triple 5 Soul’s upcoming relaunch will look like, stories about New York City in the early ’90s, her thoughts on streetwear today, and more.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

I think everyone is pleasantly surprised to hear that you’re relaunching Triple 5 Soul this year. You left the brand nearly 20 years ago. Could you explain what exactly happened to Triple 5 Soul after you left and what drew you to come back?

Basically, I was done. When I decided to depart [in the early 2000s], I just felt like my creativity was stifled and my partner in the company at the time was just so toxic. So I went on to pursue my art, I opened a cafe in Brooklyn, and ran a bed-and-breakfast in Upstate New York. I did the city-country life and raised a couple kids. Now, I feel like the timing’s right. The brand was in limbo in terms of ownership, and now some people in Canada are trying to bring it back. I’m currently working with their CFO, we put together a team, and I’m leading the creative direction again.

It’s nice to have that freedom again. And my main purpose to come back with the brand really sparked during COVID when I was sewing and making a lot of stuff. I was talking a bunch to Virgil Abloh about it. He just said, “You gotta get on your sewing machine again. You gotta start telling these stories and let the youth know about the legacy and history of this brand because it’s really important.”

For me to be creative director of the brand I founded and started has been a fun journey, because I feel like I can weave in that storytelling. We’re not looking to come back like a [retro] ’90s brand. However, we’re using our archives to push the narrative. I’m honestly really curious to explore what the youth and younger brands are doing now. I’ve just explored a bunch of them out on the West Coast and I’m so impressed by how much community is woven into people’s brands now. I feel like I was doing that in the early ’90s and that’s what made Triple 5 Soul so special. It was like a whole vibe and a whole crew of artists working together, doing each of our own things.

So what can you share about your first collection for the relaunch? It’s cool to see you’re really going back to the roots with sewing 1:1 bespoke pieces.

It’s a mashup. For the past couple years, my own art has been centered on upcycling garments. For example, I recently took old hooded sweatshirts and turned them into these chair covers. So I’m exploring that concept now for this piecework collection that will be unveiled in the relaunch. We’ll have the basic staples as well. But we’re playing around with this idea of taking the iconic pieces from the brand and mashing them into new styles. T-shirts and sweatshirts cut up in different ways. Basically, what I took away from the brand back in the day was this attention to detail. And that’s what I’m really looking to focus on for its relaunch.

Anything you can share about the new creative team?

Not really except that it’s small, energetic, creative and new. I want to let people know that it’s super inspired and we are trying to stay forward and creative while weaving the past with the present. I will say that several known artists have contributed to the brand. I’m also going to eventually cast my net to a lot of other original designers and artists. But I’m honestly more curious about what new people are doing. We’re trying to find something new. I don’t want to be this “bring back” brand where I’m just busting out all my old graphics. I’m interested in working with new artists and weaving them into my own storytelling. I want it be a mix of young artists with those from my own era.

So let’s go back to 1989. You’re a 19-year-old Pratt dropout, and streetwear isn’t even a genre of clothing yet. What was so special about New York City during this time that created many of the first streetwear brands?

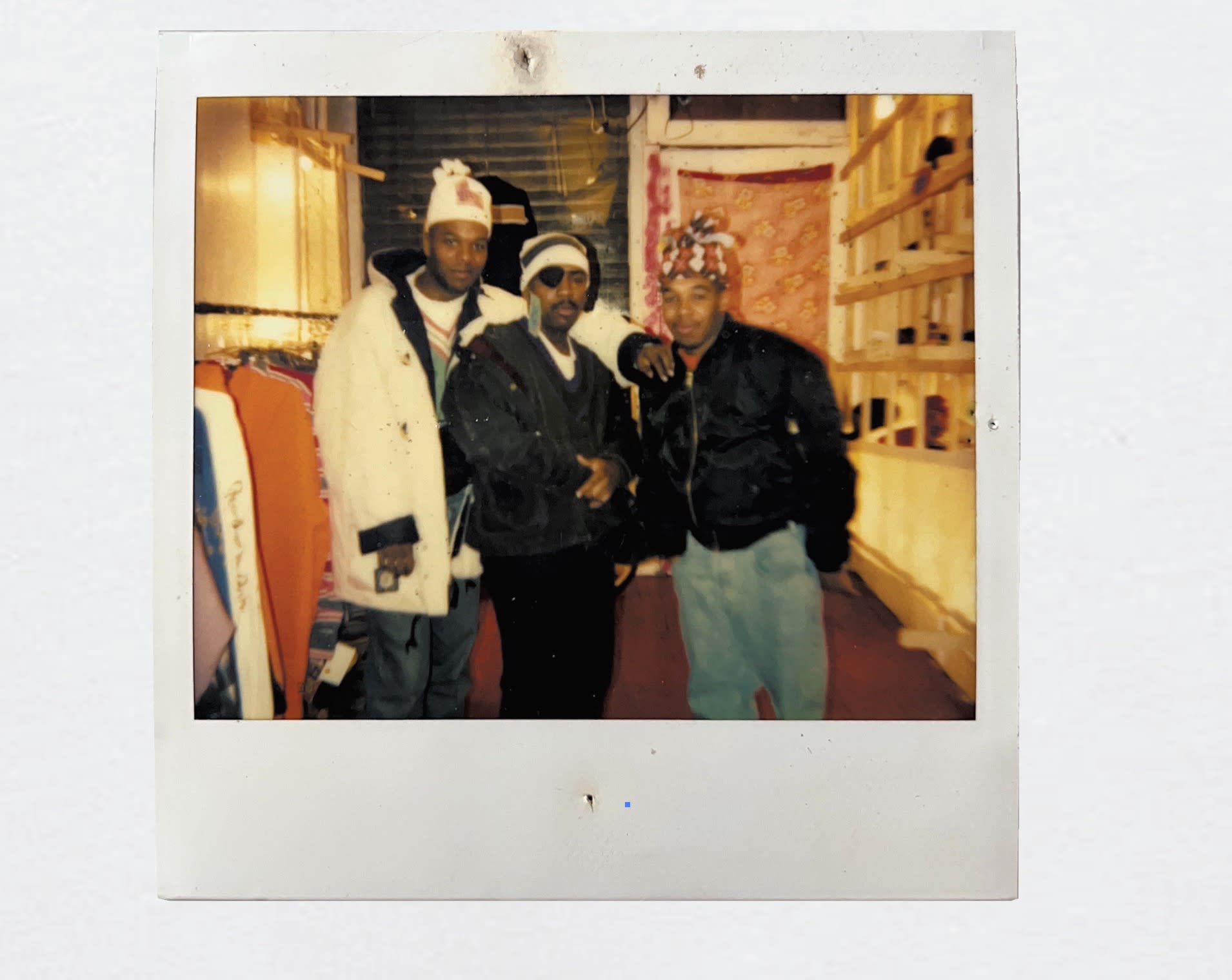

It was just the right time, because that was when New York was still gritty but also really affordable. All this was during a time when people could express themselves, make it happen, and survive as a broke young artist. I think there was, like, this real pulse that was taking place because hip-hop and other music we were around were still underground. There was this clash of genre. We’d go to clubs and hear house music with hip-hop, which you couldn’t really hear on the radio. So we had to go to these parties or get mixtapes to hear new music. The art as well. New York City was such a canvas where people could just express themselves and get their work out there just by walking down the street because of graffiti. In terms of the clubs, so many people had the platform to MC or DJ and shine. Clubs like Wetlands and S.O.B.’s were places young people could actually have a stage. I was selling my tie hats and stuff at these parties. It was a special time, and it’s hard to define it.

It’s crazy to know that you started selling Triple 5 Soul out of the Tower Records flea market, right alongside James Jebbia and Mary Ann Fusco before they even opened Union. At this moment, what was Triple 5 Soul doing exactly?

So when I had my store on Ludlow Street, I was making the tie hats, cut-and-sew hoodies, and baggy pants. So everything was kind of customized. I would buy fabric around the corner from these jobbers who basically sold deadstock fabrics. So I was upcycling without even knowing it. I would take, like, all these assorted fabrics, stack ‘em up, and cut my pattern out. Then, I would have different pieces of a hoodie, a sweatshirt body, and a sleeve that customers could pick and choose what they liked. So I think that was appealing for someone who wanted to create their own style. We had uniforms back then, but at the same time, we wanted our own style. It was one of a kind and I think that’s also why it was so appealing to Japanese customers as well, who were such visionaries for wanting to step away from their own culture and bring back new styles from New York.

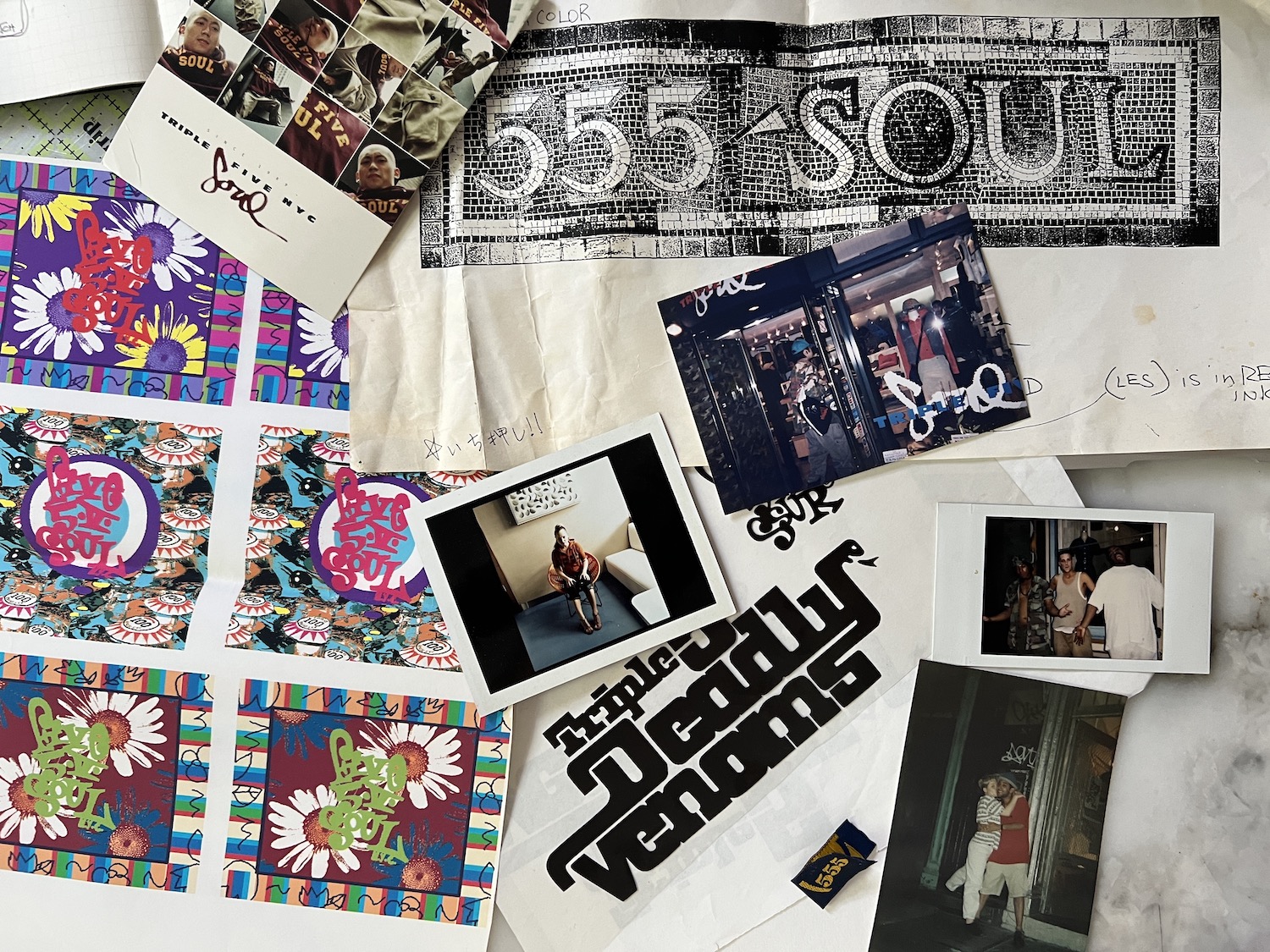

Those garments were also really colorful and striped. Striped T-shirts and striped cut-and-sew hoodies. I had these really cool logos made by [Alphanumeric co-founder] Alyasha Owerka-Moore that I was also hand silk-screening onto pieces of fabric before sewing the patch on. Since the 555 Soul labels were printed on scrap fabrics and stuff, even the logo patches were 1:1 originals.

Today, opening a store on Ludlow and Stanton is a no-brainer. But the LES was different in 1989. Why did you open there?

Well I was already living down there. I had an apartment on East Second Street across the street from a club called The World, which was like a super-fun party. I found this storefront space on Ludlow when I was about to leave Pratt. It had an apartment in the back and a store in the front with a curtain. I basically put the sewing machine in the front, and it was like a tailor shop/store/clubhouse. Friends would bring speakers to the backyard, and we’d throw MC or DJ parties. But basically, the rent was really inexpensive, and it was a place where I could have an apartment and a store. There weren’t a lot of businesses there yet.

That’s interesting to hear because I feel you were one of the first to usher in a larger retail scene there.

I mean it was like a clubhouse for sure. It was never really about me making fashion. If I did a fashion show, it was in a club at a party. Models would come out and different friends would DJ. It was more of a vibe and a party. It was very music driven. We were in the clubs and the parties like every night. That was the scene.

The store itself was really underground. Even if people knew about it, they would have a hard time finding it. I guess not being in a shopping area was part of its appeal. But people would hit us up before heading to SoHo to go to James’ store, Fat Beats, or Pat Fields. People would make their rounds and there were only a handful of really vibey stores. Soon after, you’d have stores like Alife, Liquid Sky, and other cool little shops. And if people didn’t come to my store for clothes, they came for the mixtapes.

That’s right. I heard you had a close relationship with Rawkus Records right?

Yeah, Rawkus Records wasn’t too far away. Empire Management wasn’t too far away. So we gravitated toward each other because of music and parties.

Whenever I think of Triple 5 Soul, I think about the Native Tongues movement. A Tribe Called Quest. Jungle Brothers. De La Soul especially, since Pos wore the tie hat on the cover of Paper. How did New York’s exciting hip-hop scene in the early ’90s boost the brand’s profile?

Well I have to say, Paper magazine was definitely an important magazine for Downtown New York culture and nightlife. They covered nightlife and hip-hop was happening. But obviously it wasn’t birthed Downtown. Rawkus came later and all those guys from the Native Tongues movement were from all different parts of New York. But again, I think people gravitated to Downtown during this time because we had the clubs and the parties. It was a whole movement. So things like Paper were really important because they covered house music, techno, and underground hip- hop music at the time.

I helped style that issue with De La Soul on the cover. Another time, Kim [Hastreiter], called me up to let me know that River Phoenix was coming in and asked if I could style and hang out with him. So I have a whole Paper magazine issue of River Phoenix wearing all my handmade clothes. We met, hung out, talked about being vegetarians and I took him out to a party. Downtown was this special destination. If you came from LA, Japan, or London, you knew that the clubhouse of Triple 5 Soul was in the center of it. There was this pulse and many of us were surrounded by it.

I’ve heard about the crazy parties you used to put together. What was the craziest one you ever held?

Well we did this one fashion show and I recently found a bunch of photos from it. Stash and Futura built a set for me that resembled a life-size subway car, made out of plywood, and the doors actually opened. So we set them up on a track and put them on a stage in a club. I believe it was the Grand Nightclub. I forgot who DJ’d that night, but all my friends were casted to model and they came out the subway doors. So that was pretty epic. We used to throw really great parties in Japan and I would fly out the Rock Steady Crew, Mark Ronson, and Stretch Armstrong. All of these guys are legends now but we were just coming up back then. We also definitely threw some good parties out in Vegas for the magic and ASR trade shows. Parties were always important for us.

So at what point did the brand start focusing less on bespoke garments and more on graphic hoodies and T-shirts?

It was pretty fast. Probably like 1993. As business grew I was able to release factory-made clothing. Originally I was doing it just myself but I eventually got local women to help me sew it. So I would cut a bunch of fabrics and then give them piecework stuff to sew up. Eventually, I found a friend who hooked me up with a factory in Chinatown to start making stuff. So it eventually grew into full collections that were manufactured in New York City. Then, when I partnered with Troy in 1996 and moved the store to Lafayette Street, he really helped me expand the brand, the collection, and manufacture a full range of products.

Of course, while there are brands started by graffiti writers, like PNB and Not From Concentrate, Triple 5 Soul was also ahead of its time when it came to working with graffiti artists. Aside from Stash, what graffiti writers did the brand work with?

Well all the guys from PNB Nation and I were selling their T-shirts in the store. Lee Quiñones was always a good friend of mine. Within the breakdancing world, I was close with Crazy Legs from the Rock Steady Crew and we would do all of his annual Rock Steady parties plus sponsor his events. We’d sponsor the DMC DJ battles too. I just had a lot of friends involved with all that. So when I had the capacity to do any kind of sponsorship, or “Street Team” marketing, I would go for it. We had friends go around and stencil the logo up and down Broadway or make stickers for Rawkus Records’ street team to put everywhere.

One artist I’m surprised to hear that you worked with in the ’90s was Banksy. You were on him very early.

I didn’t want to lose the integrity of the brand. So I made the store on Lafayette into a gallery. I put turntables in the store and made sure that I came to the store on Saturdays to hang out, DJ some records, or get my friends to DJ in store. But I also wanted various artists to come in and just take over the store to do whatever they want. So Ben Velez, a dear friend of mine who was running Triple 5 Soul for many years, was friends with Banksy’s manager in London. At this point he was already mythical. We’d see his monkey stencil in London like we saw Cost/Revs in New York City back in the day. So we got him to come but he stayed under the radar. We booked his flight, we reimbursed him, he showed up with a portfolio of stencils, and basically took over the store. We hung out, went out for drinks, but he didn’t come back to the opening the next night. That was like 1997 and we had Madlib and Peanut Butter Wolf DJ the opening.

It’s really crazy because during this time, it sounds like streetwear designers, with no business experience, were going to trade shows like 432f, getting huge orders, but then not being able to fulfill them. How did you pull it off?

It was definitely a hustle because when I partnered, I was already in over my head with crazy amounts of orders. I’d have to buy so much fabric. I was trying to handle all of the manufacturing myself while hanging out at the shop. Honestly, I don’t know how I did it. But I definitely winged it and it was a hustle. I honestly got lucky by partnering with someone, even if he did eventually turn out to be a toxic human being. We make these deals with the devil. It became 80% business and 20% creativity. When I partnered with him he helped me expand the business, injected some money into it, and a whole business platform. Fortunately, I brought in my people like Ben Velez who understood the culture. So I really spearheaded the marketing and the culture that maintained the brand’s integrity and kept it creative.

So I understand that when Troy Morehouse took over the brand, he changed the direction of Triple 5 Soul so much that it essentially lost its soul. I’m personally curious to know how you feel when you see cool streetwear brands get acquired by larger entities?

I mean, it doesn’t surprise me at all. I’m sure all these cool brands have some kind of backing behind them to survive and thrive. I think it’s really hard for a young person in this day and age to come out with a brand. I see it here in New York. I don’t know what’s happening in LA with all these cool vibey little spots I saw. But it wouldn’t surprise me if they had some type of investment. I’m not sure how to answer that. It’s hard to produce and make your art. To be able to make art alone, one off, and survive as an artist is a real privilege. I also see brands here and they’re making it happen and it’s a one-man show.

When you look at streetwear today what do you think about it?

Well stores like Kith and all that, is it’s own thing. But it’s nice to see smaller brands narrate their own community and vibe. It was fun to see how stores [like Brain Dead and Mister Green] in LA today have a story to tell with a whole tribe of friends building that. I think when people have a point of view and a story to tell, and not just follow the basic playbook of making clothing, putting it on some famous rapper or celeb, but going a little deeper than that to create community, is what I’m interested in.

Anything you miss from the era you came up in?

I missed the search and the find. We would go crate digging and now you just click around on Spotify. It felt like an adventure back then. I’m not saying we didn’t have to literally work for it, but we had to work for it just to find out where the party was.

But you know, people are doing that in a different way. I don’t want to knock what’s happening now. I’m more interested in the handmade and doing something slightly off-kilter and different. That’s the lane I wanna stay in when I do my art.

Speaking of Virgil, I remember seeing those messages he sent you that you shared on Instagram. He literally said that your history is vital to the fashion system we have today. When you see the larger fashion ecosystem now, where do you see Triple 5 Soul’s impact?

Well as big as the brand got, I think it’s important for people to know the history and the story of where the brand came from. The late ’80s and early ’90s in Downtown New York birthed many things. It wasn’t just streetwear, but a grassroots movement that was super creative. So it’s important for me to write my book and get those stories out there. It’s really not just about me or Triple 5 Soul. I want everyone who was around at that time, around the brand, to tell their stories too, because it’s all super valid and important.

These stories aren’t online and I haven’t shown or revealed all of my archives.

A lot of people just think it’s just Supreme. All respect to James, but there were so many brands before that or around the same time that haven’t been recognized yet or acknowledged. Like there was a whole movement that took place. And let’s not forget, I was really the only girl [Laughs]. We always joked how I’m back in the boys club now.