To see where tomorrow’s great Western PA football legends come from, be sure to check out Friday Night Tykes: Steel Country Tuesdays 9|8c only on Esquire Network.

It’s only fitting that Canton, Ohio, home of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, is just 91 miles away from Pittsburgh because Western Pennsylvania is fertile ground for football talent. The list of Hall of Famers from the area is staggering: George Blanda, Johnny Unitas, Joe Namath, Joe Montana, Jim Kelly, Dan Marino—and that’s just the quarterbacks. Mike Ditka, Curtis Martin, Tony Dorsett, Jack Ham, and Russ Grimm are also enshrined in Canton.

Ever since Pittsburgh native Art Rooney founded the Steelers in 1933, football has been part of Western Pennsylvania lore. It’s Friday Nights. It’s Pitt vs. Penn State. It’s the Steel Curtain and the Terrible Towel. There’s a reason why football is so popular in the region: Hard work and toughness, which are cornerstones of the game, are endemic traits found in Western PA. The legacy of which was then passed down to the next generation. These are the stories of four men who grew up in Western Pennsylvania and how hard work, toughness and football shaped their experiences.

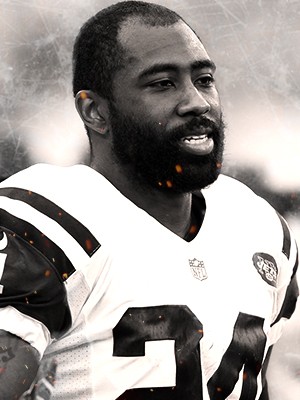

Even if LaVar Arrington did not grow up in a football family with uncles and cousins playing the game, he would have wound up on the gridiron. “That was what was expected of you,” Arrington says about growing up in Pittsburgh. “You didn’t really have a choice in the matter. You were going to play football. Football is like religion in Western PA.”

Arrington, a diehard Steelers fan from birth, got his start at the West View Pee Wee league learning more than just fundamentals like blocking and tackling. Because of how seriously Western PA takes its football, Arrington knew the difference between an A Gap and B Gap from a young age. He also studied the nuances of Pro Bowlers like Greg Lloyd and LeVon Kirkland. The head start prepared him for stardom as a linebacker at North Hills Senior High School where he won a slew of awards—1996 Parade National Player of the Year, Gatorade Player of the Year, and USA Today Pennsylvania Player of the Year. Even though he also thrived in basketball and track and field, football was what Arrington looked forward to the most. “Every Friday was Christmas,” he says. And he had one goal in mind. “It almost became an obsession to become good enough to play linebacker at Penn State. Fortunately, I got the opportunity to live that dream.”

Following in the footsteps of Dennis Onkotz, Jack Ham, Shane Conlan, and others, Arrington bolstered Penn State’s reputation as Linebacker U. He was a two-time All-American and won the Butkus Award and Lambert Award, honors given annually to college’s top linebacker, in 1999. Arrington’s lethal combination of smarts and athletic ability were most famously on display during a game against Illinois in his sophomore year. Anticipating the snap count on a fourth and short play, he soared over the offensive line to tackle the ball carrier in the backfield. The play became immortalized as The LaVar Leap.

The Washington Redskins drafted Arrington with the second overall pick in the 2000 NFL Draft. He immediately made an impact and, starting in his second season, was named to three consecutive Pro Bowls (2001-2003). But those Washington teams were dysfunctional and Arrington only made the playoffs once (2005) before departing to the New York Giants. A torn Achilles midway through the 2006 season effectively ended his career. Arrington, however, has since gone on to have a successful career in media: writing for the Washington Post, hosting the LaVar and Dukes radio show, and, currently, as a lead television analyst for NFL Network. He is also the founder and chairman of Xtreme Procision, a football training system that aims to teach the next generation of pro football players.

Although he played his last game at the young age of 28, Arrington has no regrets about his career. Football gave him so much. “I was a very introverted person. I was very insecure. I never thought I was a good looking guy. I never thought I was the coolest guy. I was almost socially awkward,” he says. “The one place that I had 100% percent confidence and felt like I mattered was in the locker room and on the field. It was my safe haven. I gave it everything that I had. For me it was so instrumental in my development as a person.”

When Darrelle Revis was a kid growing up in the small Beaver County town of Aliquippa, population 9,300 or so, he would stand outside his house on Friday nights and look in the direction of the Aliquippa Senior High School football field. “All I thought about was playing there,” Revis said to The New York Times in October 2008. “When those lights come on, everybody in this town is there. That field is what keeps the town going.”

With notable alums such as Pro Football Hall of Famer Mike Ditka, three-time Super Bowl Champion Ty Law and Revis’s uncle, the Pro Bowl defensive tackle Sean Gilbert, the Aliquippa Senior High team was seen as the first step towards a career in the National Football League. First, however, Revis would have to avoid the gangs that had permeated his small town. “It’s a tough town,” Revis said to the New York Post in January 2011. “There’s a lot of negativity there. And the one thing I did growing up is lean [on] the people doing positive things…Ty Law, my uncle Sean Gilbert, Mike Ditka’s from there. Just seeing the billboards of him from our hometown, and wanting to make it out of there.”

And not only did Revis want to make it out of Aliquippa, he wasn’t going to be satisfied just making the pros. “When I was growing up, I looked at the people who made it to the NFL,” Revis said to The New York Times. “But I wanted to be better than them. I wanted to surpass them.”

After terrorizing the Big East as a starting cornerback for his hometown Pitt Panthers, Revis left school after his junior season to enter the 2007 NFL Draft. Sensing an available franchise cornerback, the New York Jets traded up to select Revis with the 14th pick. Revis surpassed their expectations.

Perhaps the best man-to-man cornerback the NFL has seen since Deion Sanders’ mid-1990’s heyday, Darrelle Revis is widely considered the industry benchmark for shutdown cover corners. He is a 7-time Pro Bowler (2008-2011, 2013-2015), and the 2009 AFC Defensive Player of the Year. More than any awards, Revis’s dominance is conveyed by his nickname: Revis Island, a spot where opposing wide receivers often go missing.

How does Revis do it? Though not a speedster like Sanders, he has an uncanny ability to stay with the receiver, using leverage, angles and power to win battles. His greatest attribute, however, is that he is one of the games hardest workers. No one is better prepared. Through intense film sessions, Revis knows the book on all his opponents. Sometimes it appears that he knows what routes are coming.

Perhaps there is no better example of Revis’ grit and determination than his comeback following ACL surgery in 2012. He made the Pro Bowl upon his return in 2013 and then won Super Bowl XLIX with the New England Patriots in February 2015.

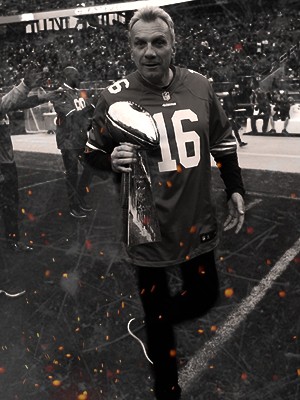

Perhaps no moment better explains Joe Montana’s nickname of Joe Cool than when he trotted onto the field late in the fourth quarter of Super Bowl XXIII with his San Francisco 49ers down three points to the Cincinnati Bengals. As the 49ers huddled up, with their season hanging in the balance, Montana turned to offensive lineman Harris Barton and asked, “There, in the stands, standing near the exit ramp…Isn’t that John Candy?” Unfazed, Montana would lead the 49ers on a 92-yard game-winning drive, completing eight-of-nine passes including a 10-yard touchdown to John Taylor with 34 seconds remaining.

Joe Cool’s uncanny ability to stay calm within the chaos is one of the reasons why he is one of the greatest quarterbacks of all time and the ultimate winner at the position. He is a four-time Super Bowl Champion (XVI, XIX, XXIII, XXIV) with an 11-0 touchdown-to-interception ratio in those games, three-time Super Bowl Most Valuable Player (XVI, XIX, XXIV), eight-time Pro Bowler, two-time league MVP, and member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

The grandchild of Italian immigrants, Montana’s journey began in New Eagle, PA., but he grew up in Monongahela, a small town with a population of approximately 4,300. Montana’s father, who ran a loan company, taught him the game, and his wife Theresa instilled a winning attitude in their son. “They taught me to never quit and to strive to be the best,” Montana said during his Hall of Fame induction speech in 2000, “Because there is only one reason of doing anything that you set out to do: If you don’t want to be the best, there’s no reason going out and trying to accomplish anything.”

It took some time for Montana to prove that he was the best. He sat on the bench his first two seasons at Ringgold High School before ascending to the starting job; Ringgold High’s football team now plays at Joe Montana Stadium. Further pushing him, he looked at football as a golden ticket. “I just think a lot of it was the pressure of getting out,” Montana told Trib Total Media in 2015. “Back then we had the coal mines and the steel mills along the rivers, and life was a little different back then. You saw sports as a way to get out of that lifestyle. I knew I would’ve never been able to go to Notre Dame — my mom and dad would’ve never been able to afford it.”

Montana also overcame adversity at Notre Dame, starting his career as the seventh-string quarterback before eventually leading the Fighting Irish to the 1977 National Championship. NFL scouts, however, weren’t convinced of Montana’s ability, and he slipped to the third round of the 1979 NFL Draft. Montana didn’t have the same superior arm strength as fellow Western PA, Hall of Fame quarterbacks Johnny Unitas, Jim Kelly and Dan Marino, but he was a mobile quarterback with great instincts, accuracy, instincts, and, of course, the ability to keep cool under pressure.

When Dan Marino would come home from school, his father, Dan Marino Sr., would be there waiting for him with a football ready to play catch in the backyard. “Nothing against Jackie Sherrill or Don Shula, but he was the best coach I ever had,” Marino told NFL Films in 2015, making sure not to slight his head coaches at the University of Pittsburgh and the Miami Dolphins, respectively.

Marino Sr., who delivered papers for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, taught his son what would become one of the most feared weapons in NFL history: Marino’s lightning quick release. During their backyard training sessions, he wouldn’t allow Dan to bring the ball behind his ear when he threw, pushing him to snap his wrist on each toss. He stressed the concept of not wasting any motion. He also understood the concept of hard work that stems from growing up in Pittsburgh. “I think it’s just the people, the experience that you’ve had growing up here,” he told NFL Films in 2015. “I remember being just competitive. I mean, the games I played on the streets were just as hard as any game in organized sports.”

Marino took those tools with him—which by now also included a rocket arm—to Central Catholic High School and later to the University of Pittsburgh where he started as a freshman. But after a lackluster senior campaign, Marino’s draft stock dropped and he was selected 27th overall in the 1983 NFL Draft—the sixth quarterback selected in the heralded draft class.

Marino set out to prove the doubters wrong, taking over the starting job in midseason to lead the Miami Dolphins to the playoffs and earning the first of nine Pro Bowl selections. He quickly topped his rookie campaign with, what was at the time, the greatest single season for a quarterback. In 1984, Marino broke six single-season passing records, including most touchdown passes (48) and most passing yards (5,084) on his way to winning the NFL’s Most Valuable Player. But the Miami Dolphins lost Super Bowl XIX 38-16 to the San Francisco 49ers.

Marino never made another Super Bowl, but when he retired in 2000, he held nearly every major passing record, including the single seasons and career marks for passing yards and touchdown. He also helped revolutionize the sport, as most teams today ran some form of the Dolphins pass-heavy offense from the mid-1980’s. It was a dream fulfilled for a kid who grew up tossing footballs in the backyard with his old man. “I didn’t know I was going to be a professional athlete,” Marino said in 2015 after being honored with a plaque at Central Catholic. “I didn’t know I was going to be in the Hall of Fame, but I always dreamt about it.”