While the men who would create the American Mafia were ruthless and lawless, it is all too easy to transpose their story onto the classic image of the American Dream.

These were men determined to succeed against all odds, planting roots in Manhattan and Brooklyn, Philadelphia, Chicago, New Orleans, and Detroit—many of the exact same places where, generations later, hip-hop’s stars would be born.

Congress enacted Prohibition in 1920, forbidding the sale of alcohol, and, almost simultaneously, invented the market for bootleg liquor.

Gangsters making money as loan sharks and casino operators were now becoming millionaires as bootleggers.

The Prohibition-era underworld became the impetus for the modern HBO drama Boardwalk Empire, set in Atlantic City. The fictionalized series revolves around the ruthless political figure Enoch “Nucky” Thompson, modeled after his real-life counterpart Enoch Johnson, a prominent New Jersey gangster-politician.

The inimitable Steve Buscemi plays Thompson, but the character that really captured the hearts of fans is Michael Kenneth Williams’ Chalky White. (Williams’ fans have likely been following him since his days as the beloved character Omar Little in The Wire, another HBO smash.) Williams is an altogether different force to be reckoned with on Boardwalk, playing a successful black gangster in Jersey’s white-domineered racketeering game. Williams turns the archetypical gangster character into a multi-dimensional icon, which might be why his roles attract such a wide fan base.

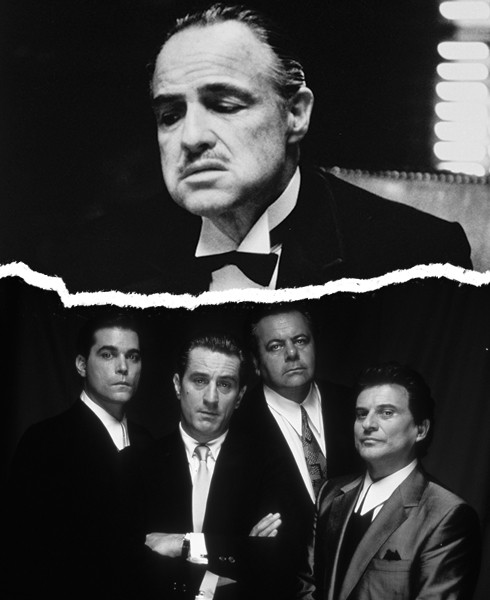

The late 1960s brought a watershed moment for the Mafia in American popular culture. In 1969, author Mario Puzo published his book The Godfather, and the rest was history. The film The Godfather (1972) and its sequel, The Godfather II (1974), would both win the Oscar for Best Picture, and the saga of the Corleone family would inspire generations of rappers and aspiring hip-hop moguls.

The next several decades would see a number of culturally significant Mafia movies come along, one of the most important being Martin Scorsese’s GoodFellas (1990), which introduced the world to a young actor named Ray Liotta.

Actor Ray Liotta has earned a cult following by playing “tough guy” characters in film and TV. Liotta is best known for playing the New York City Mafioso Henry Hill in Martin Scorsese’s classic film, GoodFellas. The film provides a window into the rise and fall of the American Mafia in NYC—particularly that of real-life crime family, the Luccheses.

Further carving out his niche as an actor well-suited to play strong, determined leaders, Liotta starred in The Rat Pack as the mob-associated singer Frank Sinatra. Liotta continued down this path in crime dramas like Narc, Killing Them Softly, and The Place Beyond the Pines. In each case, he showcased a broad range of emotion and acting chops, keeping his fans on the edge of their seats.

Meanwhile, in the real world of organized crime, the power of the Mafia was beginning to decline. But in the world of hip-hop, the Mafioso lifestyle was still the standard by which all success was measured. Whether it was the gangsters of the early days, or a more modern icon like Scarface’s Tony Montana, mobsters were officially hip-hop heroes.

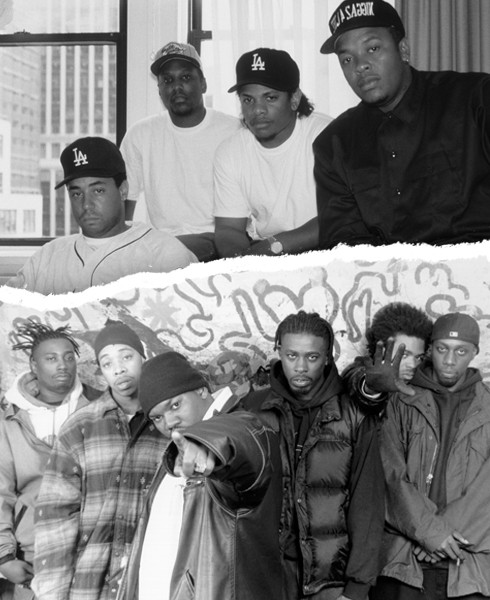

In 1992, right around the time N.W.A. was popularizing a genre of hip-hop called “gangsta rap,” the Mafia’s last true kingpin, John Gotti, was convicted on multiple charges. Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano, an underboss turned snitch, testified against him. From that day forward, the Mafia was never the same.

Nonetheless, hip-hop groups were styling themselves after notable La Cosa Nostra houses. The Wu-Tang Clan once dubbed themselves the Wu-Gambinos, and took on additional rapper names based on old Mafia figures. Snoop Dogg’s second LP was called The Doggfather. Nas’ video for the song “Street Dreams” is essentially a four-minute homage to the Scorsese Vegas-set gangster movie Casino. Hip-hip producer Irving Lorenzo even took the name “Irv Gotti,” and named his company Murder, Inc., after a syndicate that Bugsy Siegel once belonged to.

Following the model of the Mafia’s core houses, record labels like Death Row, Bad Boy, and No Limit presented themselves as giant families—and artists pledged loyalty to that family.

Interestingly, the Mafioso mentality in hip-hop hit a peak and then faded away, much as it has in American organized crime. The label heads who styled themselves after Mafia Dons have mostly been pushed out of the game in favor of leaders with greater artistic vision.

Hip-hop groups like A$AP Mob, TDE, YMCMB, and OVO Sound will always be about family. But now it’s about these families working together, not against one another. Today’s hip-hop culture seems poised to replicate the moment in 1931 when The Commission first came together; 21st century hip-hop is proof that “our thing” can not only survive, but also thrive.