It feels like way more than a cosmic coincidence that mere months after FX's The People v. O.J. swept popular culture, ESPN is airing a five-part, seven-and-a-half hour docuseries entitled O.J.: Made in America. The story of O.J. Simpson and his trial is an endlessly enthralling topic, but its thrust back into consciousness in 2016 has been surprising. As a teen who was somewhat able to follow the scandal as it was unfolding, it's been interesting to revisit the immense story, and to have old memories brought up by The People v. O.J.

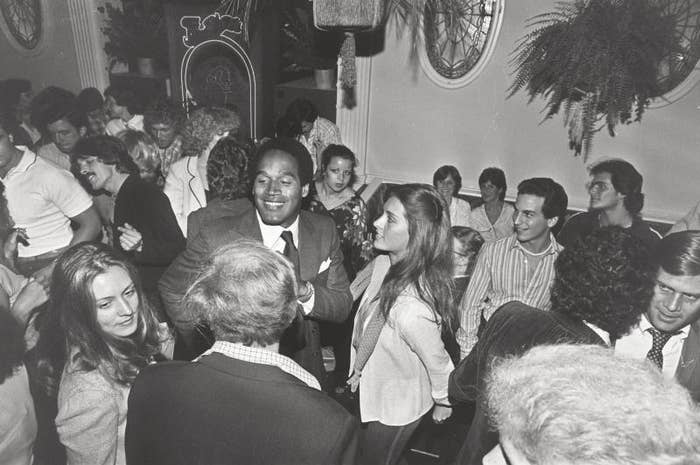

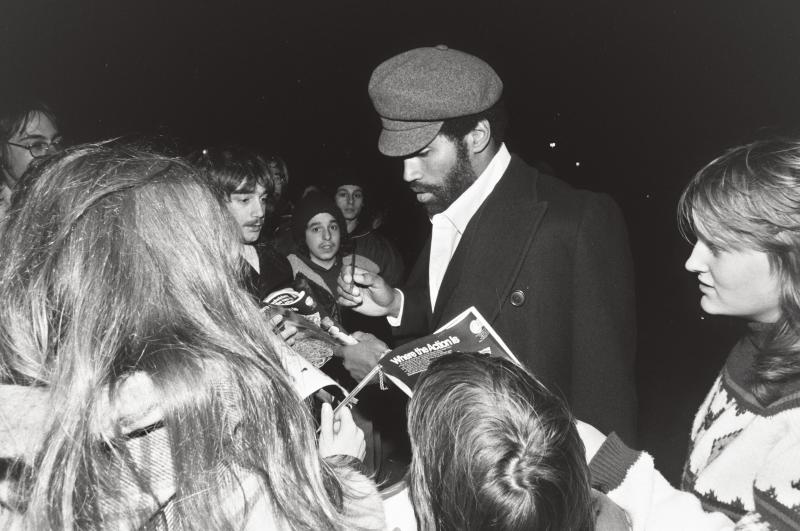

Still, I wasn't prepared for O.J.: Made In America. Having seen the first two parts of this epic series, it's been intriguing to see the story of O.J. Simpson told in parallel to the issues that were going on in America right alongside of him, from the racial injustice he lived through as a youth to the LAPD and their reign of terror during O.J.'s post-NFL life, when he solidified his celebrity in TV and film. It's a tale that, frankly, most black people have understood and recognized back in the mid-'90s, but one that others might not have picked up on, for whatever reason. And Made in America pulls at every tiny thread of the factors that contributed to the story of O.J., until everything is completely unspooled.

Ahead of the premiere of the first part of O.J.: Made In America on June 11, we caught up with the film's writer and director Ezra Edelman, who took on this project and turned it into an epic look at the creation and destruction of one of America's most recognized figures. Edelman's filmography already includes the Emmy Award-winning Brooklyn Dodgers: The Ghosts of Flatbush and the HBO Sports documentary Magic & Bird: A Courtship of Rivals, but it was time to take a look at this series, which turned into both a massive undertaking and the definitive look at O.J. Simpson.

With O.J.: Made In America running seven-and-a-half hours, that’s a huge amount of time to spend on any one particular subject. I'd read that ESPN brought the project to you and you were kind of reluctant. What was the reason behind that, not necessarily wanting to get involved with this particular story?

I had no interest in spending however much time of my life thinking about O.J. And more importantly, I didn’t think there was anything to add to the story.

So what made you eventually accept the project?

Well, the only reason I accepted the project was because the initial concept was for it to be five hours for television. And while I wasn’t interested, frankly, in O.J., and I couldn’t be less interested in the question of did he do it or did he not do it, the canvas, even at that initial concept of five hours, was large enough that I knew I could tell a story about these other things that did interest me. Which was, I was interested in L.A., I was interested in the community’s relationship with the police. I was interested in this social history that, to me, gets short shrift in this story. But having said that, it’s still so fundamental to understanding the story and the trial in ’94 and ’95. That was the thing that got me into it.

How did you go about shaping the story in this way?

I knew I had to tell a story about O.J., and I knew I had to satisfy my own curiosity and others in terms of trying to do as deep a dive into him as a man as possible. But, that wasn’t solely going to be the film. I think the way all the things have been done when it comes to this trial—the stories that have been told, in book form but also in television or documentary form—they miss it. It’s like, nothing gets explained. What people seem to want to leave off on are, "Oh, here are these images. Here are these images of black people cheering and white people crying and then white people are angry at black people." It’s like, "Okay, but why?" And it’s strange to be put in a position where you feel like you have to create some primer for white people to understand something that is fundamentally not that confusing.

At all.

I mean, not at all. And so the reason why the first three hours exist in the way it does was, well, I’m gonna make you sit and emotionally engage with this history, with these events, so maybe you, as a viewer, might empathize. You might feel something. So by the time you get to the trial, you are not so fixated on the character himself and whether he may or may have not done it. By the time you get to the end of it, as a white person, you might say, “Oh well, I didn’t realize all that stuff that happened before. I am actually looking at this through a different lens and then when I see people responding to this, I’m looking at this in a different light. I’m no longer looking in a light of, 'Oh my god, they’re really cheering a murderer.' No, I’m looking at it as, 'Oh my god, they’ve gone through a lot of shit.'”

With O.J.: Made In America being seven-and-a-half hours long, full of tons of footage and photos, I have to wonder, how long did the entire process take?

It was about two years. I probably started working in earnest myself in May of 2014. Then I spent the first few months and, literally that entire summer, just reading. Reading, thinking, sort of absorbing all the material I could get my hands on. Then I started hiring people in August of that year, and we were shooting by the end of October. And in some ways I just finished, like, two weeks ago, in terms of the final touches. It's been a very intense year and a half from the time people started working to the finished product.

Would you say you had the entire arc of the documentary laid out early, or did things change as time went on?

Thankfully for something like this, when you’re making something this long, it helps that, to me, the basic chronology is necessary in this way. To me it augments the story I was hoping to tell. You have to live with that history in a chronological fashion to then sort of see how that affected that. I think the power in the story is from the beginning of the film, to open up with a guy who is as fresh-faced and handsome and innocent-seeming as he is, to the guy that we get to at the end. You need to live through that. And I think that that at least helped me, structurally.

Were you big into the trial or O.J. as an athlete and an actor when you were younger?

I don’t know if I would say “big into” O.J. I didn’t watch the trial—I was in college, I didn’t care. I watched the chase, I watched the verdict, but it’s like someone sliced a whole part of my brain and I don’t know that I watched anything besides that. I obviously knew enough about it to know to go home the day of the verdict and watch it, but that was about it.

And what about O.J. himself?

I mean, he’s O.J. He’s a part of my life like he was a part of anybody’s life. There’s a picture of my brother on the wall in my parents’ house, still, wearing an O.J. jersey. O.J. was just a fundamental part of my upbringing in that way. I’m a sports fan. I watched O.J. on TV every week on NBC or on First & Ten on HBO. He was just there. He had the same effect on me that he would have on a lot of black youth in America. For me, that certainly informs the notion of, yeah, I have that cognitive dissonance that sort of sets in when you hear that this guy is not only on the lam in a Bronco on the freeway, but that he’s being accused of murdering his ex-wife. You’re like, “That guy? That doesn’t make any sense!” That’s who O.J. was to me.

What were your thoughts initially when you heard that FX 's American Crime Story series was going to be a thing, and kick off with The People v. O.J. Simpson? Were you frustrated or anything when you heard that this was coming out before your project?

I have to start being nicer about this, but like, yeah, of course I wasn’t happy. You’re working on doing something about O.J., and really no one’s gone there.

Exactly.

You’re already doing something that’s going to exceed the time that you’ve been given. Then you hear something else is happening. What are the chances that someone else is doing another ten-hour thing about the same subject? Like, what the fuck? So yeah, it was frustrating, but there’s nothing you can do about it. The fact is, it wasn’t a ten-hour documentary, it was a dramatization. Having said that, the concern was, if that’s on, and it was so well-received both by viewers and critics, will people really have the appetite to watch an eight-hour documentary about O.J.? That’s the fear. You want your work to be seen.

Of course.

I intellectually understood that whatever that show was was not going to change the work that we did. But you also don’t want to be swallowed whole by this thing. What I underestimated was people’s fascination with the story. Sitting here now, yeah, it was a good thing. I don’t know about you personally, but I don’t know if other people would be so engaged with sitting and talking to me about this if that thing didn’t exist. So in some ways it did an extraordinary service to us. It put this story and him back into the zeitgeist. [People] want more.

I think one of the things with your documentary is that the FX show is almost a really easy softball—it was very engaging, and for a certain segment of the audience, they might have heard about O.J. and the trial, but they weren’t alive when the chase was going on…

—sorry to cut you off, but that's also the other thing. If you’re a storyteller, you want people to watch the story through your film. For those who would’ve come to the story for the first time not knowing anything, I would still prefer them to have watched the story from our film first. That’s the other frustration.

Again, I have no beef at all with that show and I’m sure it’s great. Someday I’ll watch it. They did ten hours of what is three hours for us; if you’ve seen that show, there are some times [watching my film] where you’re going to go, “Oh, I saw that.” Or it’ll be framed in a different way, like, “Oh that’s interesting, that’s actually what happened, because I watched that in the show” versus just, like, “I’m just watching the story.” And that’s the difference.

After devoting yourself to this for two-plus years, are you suffering from an O.J. hangover right now?

I’m really trying to, like, escape this. That intensity I spoke of, there has been an overhang. I really am trying to figure out a way to have some peace and quiet to flush this out of my system before I can actually think of what I want to do. Because, I mean, it’s weird after doing a doc that’s almost eight hours long. It’s sort of like, so what do you do now? And I don’t know. I’m trying to figure that shit out.