It’s 2015 and we’re in the era of Soundcloud, Spotify and Beats 1. But back in the early 90s, it wasn’t these corporate juggernauts that broke the hottest new rappers. In 1989, young Def Jam talent scout Bobbito Garcia and undergrad DJ Stretch Armstrong teamed up to do a hip-hop show on Columbia University’s college radio, and it quickly became one of the most influential shows in rap history. How influential? Here’s just some of the artists that kicked verses on the show prior to being signed: Nas, Jay Z, Wu-Tang Clan, Mobb Deep, DMX, Fat Joe, Redman, Big L, Cam’ron, MF Doom, Eminem, Mos Def, Big Pun… If you were a successful East Coast rapper in the 90s, Stretch and Bobbito almost definitely had something to do with your success.

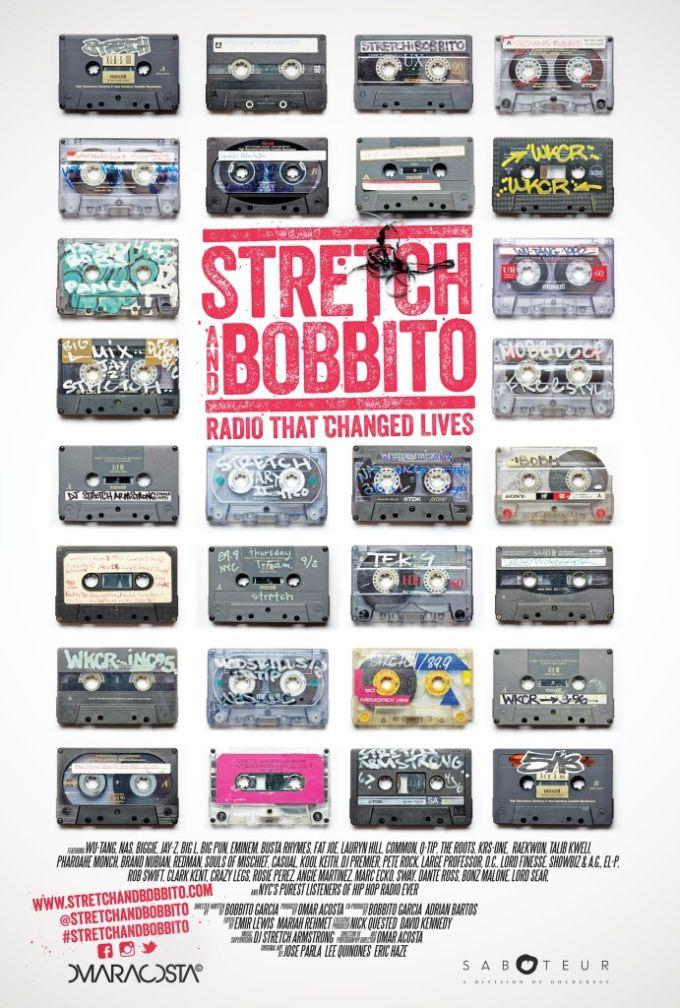

Now, on the 25th anniversary of their first show, they’ve put together a documentary about how this tiny New York college station show changed hip-hop. Stretch and Bobbito: Radio That Changed Lives is full of incredible archive footage of your favourite rappers on the cusp of greatness, from a Notorious BIG freestyle that hasn’t been heard for 20 years, to a star making turn from an unsigned Jay Z. It has its European premiere this week at the London Film Festival, and we spoke to Stretch and Bob themselves about those classic shows, hanging out in London, and how radio has changed since the 90s.

What was it like making a film about your own lives like, going back and interviewing all these guys 20 years later?

Stretch: Doing these interviews with the artists was incredible. To put the headphones on these guys and take them back to a very special moment when they weren’t rich, weren’t famous, when they didn’t know what would happen to them. To get on our show when they did, it was such a big deal for them—and a big deal for us. Making the film we realised there was a mutual respect, a mutual awe. Even though the artists weren’t famous, Bob and I really revered them, as lyricists and performers. But what we learned making the film is that artists would come up to the show, and they would be nervous, and intimidated, in the same way we were about them! When someone like Nas came to the studio, I was like “We gotta be on our tippie toes and come correct!”—but they were thinking the same thing! I wasn’t aware of that until making the film.

We were just as happy to support those that wanted to come to the show and express themselves.

So has making the film, and talking to Nas, or Busta Rhymes or Jay-Z or Raekwon or whoever for it, really made you revaluate those years?

S: For sure. Nas said to us “I wrote my first album listening to your show.” He said he would actually record instrumentals we were using as mic breaks and use them to write rhymes that would eventually become Illmatic. That just blew us away.

Which artist are you most proud of breaking?

Bobbito: All of them really. I’m just as proud as breaking the likes of Big L, and O.C., and Cage, who didn’t end up becoming these across the board stars. We were just as happy to support those that wanted to come to the show and express themselves.

One of the best bits in the film is you rediscovering a Biggie freestyle that you though was lost, that you’d forgot to record live. Had you really not heard it for 20 years?

S: That was the first time either of us had heard it since it happened.

B: And the reaction that you see in the film is genuine—we were shocked!

How on earth did you forget to record it at the time?!

B: Ha! I mean we didn’t know that he was going to end up becoming ‘that dude’. But he also came up really late, maybe 3.45am, 4am.

S: I was only interested in recording at least half a show. So if I couldn’t find a blank cassette to record for at least an hour or 90 minutes, I just wouldn’t bring anything. And Bob would at least press record when someone was about to get on the mic. It just didn’t happen this time!

B: And the thing is, his wasn’t the only freestyle that was missing, but we were always able to track the other ones down, through our network. “Yo, did you tape this last night?” “Oh yeah I got it.” But I can tell you, after that night there wasn’t another freestyle that I missed!

Ol' dirty bastard used to call up our show from payphones and kick verses.

The freestyle that an unsigned Jay Z did with Big L in ’95 on the show is seen as being pivotal to getting him noticed. When it was happening, did you have any idea that you were witnessing history, and breaking one of the biggest rappers, one of the biggest music superstars even, of all time?

B: We had no idea. There were a hundred special moments like that on the show, but then the artist wouldn’t go onto that level of fame. So you can never predict it. Jay didn’t even know. I mean, I think he had a sense that he was going to become really accomplished, because he was just so arrogant. I remember at the time thinking to myself “Why is this guy so cocky?!” {Laughs} He didn’t have an album deal, or distribution, but he just had a vision.

There are some cool stories about the young Wu-Tang Clan in the film as well…

B: All of those dude, particularly Ol’ Dirty, were super appreciative for what we did for them. ODB used to call up our show from payphones and kick verses—and at this point he was a member of a platinum selling group. He was calling us up at 3.30am like he was a 16-year-old unsigned artist! I use him as an example of how all these guy were genuine hip-hop heads, who knew that our show meant something more than just a show.

One of the last big moments for the show was Eminem coming to New York in 1998. Do you think he’d become as big as he would?

S: No, again I think like with Jay Z, we didn’t know he was going to become one of the biggest selling artists in pop music history. But I think what we were aware of was that we were finally seeing the results of the seeds—that in some way we planted—of a new generation of kids from other regions that grew up listening to the music. And that were white. This was the spreading of hip-hop. And it was also at a point when I was almost done with WKCR, and Bob and I weren’t really clicking—that moment was special not just for Em and Royce Da 5’9”, but also for us, because it reminded us what it used to be like. It was a fun night when at that point, week to week, it wasn’t fun.

The UK has always been that first frontier out of NEW YORK that really understood lyrics and beats.

We’re now in the era of Soundcloud, Spotify and Beats 1—do you think it’s still possible for anything to have an impact like your show did?

S: We can tell you what we think, you might disagree! {laughs} The digital revolution has changed everything. Not just the sheer volume of programmes playing music, but also the amount of artists, and music being made. So no. I think the pace at which people make and consume music is so drastically different. In the 80s and 90s, it was a very deliberate process, it took a lot of time and a lot of people. It didn’t mean that the records were always good, but it meant that we got less records, so we were able to pay more attention to it—it meant more when we did love it. Now it’s a schizophrenic onslaught of track after track after track. I think that attention is really missing and it’ll never happen again. I’m sure there’s a lot going on, but I don’t get the sense that there’s one place where the kids have to check it out every week to get the fix.

You were essentially on a small station, only available in New York—there’s a lot in the film about people staying up to tape the show, and then sending them all over the world. Did those limited resources, and keeping it local make it more special?

B: Absolutely. Accessibility in hip-hop is not always a great thing. The best moments are when people have to make the most effort to participate. It added to the mythology of our show, because you might have missed it. Now if someone has a great freestyle, it’s archived, it’s streamed. But for us, those who were able to get a copy of that cassette, it was like a badge of honour. And we had a lot of love in the UK. A lot. The UK has always been that sort-of first frontier out of NY that really understood lyrics and beats.