The revolution started with a kick.

At the turn of the millennium, we communicated with friends and high school crushes after class by way of desktops and house phones. The cell phone was still more corporate than it was cool. Palm Pilots, Nokias, Blackberrys, Motorola two-way pagers, and Razrs were the rage then—but the companies behind them weren’t concerned with marketing to young people, the ones who’d surf Yahoo! and AIM chat rooms on a dial-up connected desktop before thinking of saving up their lunch money for a device geared toward the business-centric.

Things changed when three former Apple employees formed Danger Research Inc. in Palo Alto, Calif., in early 2000. The Danger founders, Andy Rubin, Matt Hershenson, and Joe Britt, wanted to create an “end-to-end wireless Internet solution focused on affordability and great user experience.” How they were going to do that was a mystery then, because they weren’t sure how they were going to do it. But with mystery, comes hype. After securing $11 million in funding near the end of 2000, it was revealed: The company created what was essentially a miniature computer that fit on your hip. They called it the Hiptop, naturally. You might know it as the Sidekick.

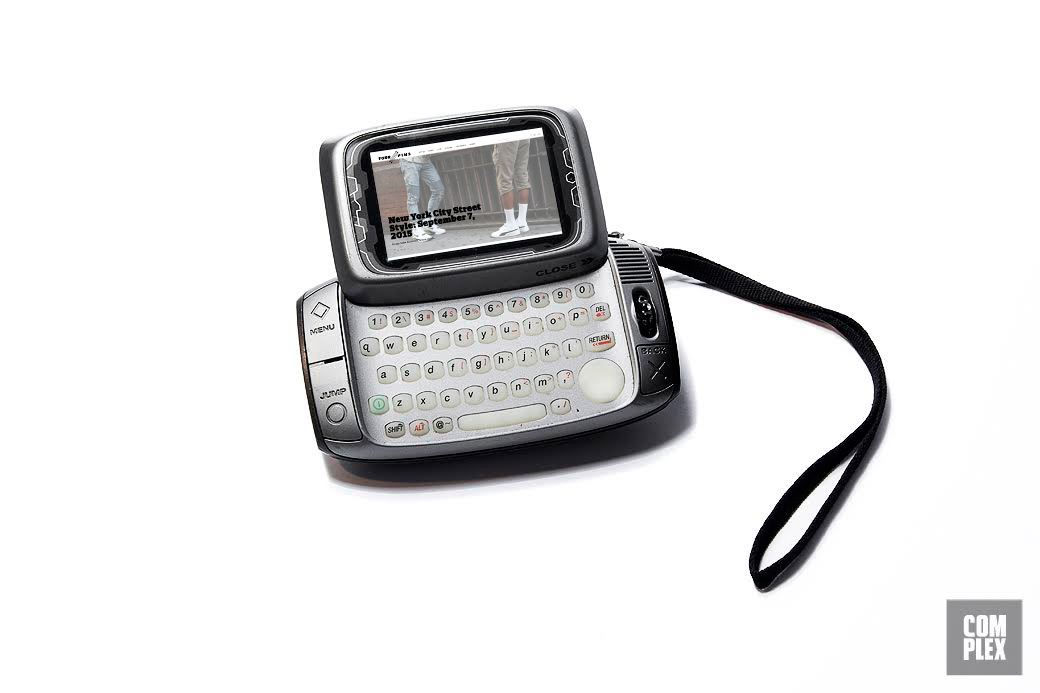

Sidekick debuted under carrier T-Mobile and popularized the concept of mobile Internet, which became a key selling point for tech companies in the coming decade. Can’t wait to hit up that girl on AIM after school? Now you didn’t have to, because AIM was in your pocket equipped with a QWERTY keyboard you could “kick” out. Today, this type of convenience is standard. Back then, it was innovative. While it wasn’t perfect—later versions of the phone came with a low-end camera, and Internet connections could be excruciatingly slow—this was power in your pocket. It wasn’t the first smartphone, but the Sidekick helped draw a distinct line between what it was (and wanted to be), and what other devices on the market were. It was smart. It was cool. It launched an era where technology converged with style, Internet meshed with portability, and carved out a place for portable devices to become a sleek status symbol for youth culture, not just for the suits on Wall Street.

The Sidekick became the go-to choice of celebrities and the urban community—and was until physical keyboards went the way of the dinosaurs. The Sidekick Story is a wild one, and if the answer to its success could be split in halves, it would be made up of one half guts and design, and another half expertly executed marketing. The device’s decade of existence saw it make its way into music videos, commercials, awards shows, a hacking scandal, and on every athlete and A- to B-list celebrity in Tinseltown. The Sidekick didn’t always have its signature swivel screen, and it didn’t always radiate coolness, especially at its inception. In fact, the first iteration of what became Danger’s first device was nicknamed “Peanut.”

In 2000, Danger Inc. had a vision to make data from the Internet accessible to the average person on the go. The company developed the Peanut, a small, affordable, nut-shaped device that would attach to a keychain, with the intention of letting people download their information from the Internet using FM radio waves, said Chris DeSalvo, who was recruited to Danger that year, in a post on Medium. Not exactly iCloud, but the idea was there.

“It was designed to be an extremely low-cost thing that you could use to carry information with you,” said Danger co-founder Joe Britt during a talk at Stanford in 2004. “The Internet bubble hadn’t burst yet and a lot of the big portal players, like Excite and Yahoo, and the smaller ones like win.com, were trying to come up with ways to make their users loyal to their brand. And so the original idea was an extremely low-cost product, something in the physical world that they could give away to users to make them stick to their website.”

“It reminds me of Apple’s early days and the focus on

building products easy enough for anyone to use.”—Steve Wozniak

The problem with Peanut, which included a processor from Tamagotchi (yes, that Tamagotchi), was that there wasn’t a good enough wireless infrastructure to transfer data to the device when it wasn’t connected to a desktop. According to DeSalvo, a VC partner found a solution to their data problem in a company providing general packet radio service (GPRS). Turns out that company, VoiceStream, was on the lookout for a device to try out on its network. After a series of events, VoiceStream turned into T-Mobile. Landing its first customer also earned it a multi-million dollar investment, and Danger started work on something different—a device that would be connected, all the time.

One of the first prototypes to this device was the “Paperback,” which looked more like a Texas Instruments calculator than a phone. It did, however, feature a full QWERTY keyboard with a small directional pad in its lower right corner.

What evolved into the “Hiptop” didn’t take the shape we know until a prototype dubbed “Navi.” The biggest change from the Paperback prototype to the Navi was the size and placement of the screen and silicone keyboard, which gave it the look of a bite-sized laptop. With a body structure in place, work went into the brains and guts. Features like AIM, Yahoo!, MSN Messenger, email, web apps, and a web browser were added.

“One of the big differentiators between the Danger device and all the other PDA and phone-like devices is that all of your data is backed-up on the service,” Britt explained.

They even destroyed a Hiptop in front of an audience at CES to prove that point. “Our presenter typed a quote into a Hiptop and then put it on the ground and dropped a bowling ball on it,” DeSalvo said. “The Hiptop was destroyed. He then removed the SIM card, plugged it into another Hiptop, signed into the same account and seconds later there was the Notes app with the quote fully restored. Much applause.”

In Sept. 2001, Danger unveiled the first official version of the Hiptop in La Jolla, Calif., about a month before Apple released the first iPod. “Cell phones are great for voice calls but users are restricted to less than one percent of the Internet and must use number keypads to interact with data,” said Danger’s then-CEO Andy Rubin. “Two-way pagers have made important contributions such as the thumb keyboard, but fall short on usability, attachments, graphics, sound, and style. The Hiptop solves these shortcomings and delivers the entire Internet at your fingertips.”

If having three ex-Apple employees wasn’t enough, the December after the unveiling, Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak was elected to Danger’s board of directors. “It reminds me of Apple’s early days and the focus on building products easy enough for anyone to use,” Wozniak said of Danger.

The following year, in Oct. 2002, T-Mobile released the Hiptop under a rebranded name—the Sidekick.

Danger and T-Mobile introduced the phone at $199 after rebate, with unlimited data usage at $39.99 a month. Similar to how iOS works with Apple devices, Danger handled the Sidekick’s data.

If you got your hands on an original Sidekick today, you’d immediately notice one thing: It’s heavy. Like, people-actually-put-this-in-their-pockets? heavy. And people did. It was a massive hulk of machinery that wanted to be your all-in-one device. But not everyone was sold. One NBC review called it “Tragically Hip,” and praised it more as a handheld than a phone. Clocking in at more than an inch from front to back, another reviewer said, “It is so thick it needs a personal fitness trainer.” Regardless, its 180-degree spinning monochrome screen and large keyboard made the Sidekick instantly recognizable. There wasn’t anything like it—it was one part Gameboy, one part BlackBerry. It wasn’t just the switchblade-like sliding screen that made the phone stylish, but the comfortable spacing of its buttons that made quick texting possible (smartphones without physical keyboards struggle today with this), and Danger’s smooth running OS. It was a seemingly graceful device that invited users to play with it. The Sidekick didn’t have a steep learning curve, and was also popular with the deaf and hard of hearing community, thanks to its full size keyboard and compatibility with hearing aids and cochlear implants.

But features alone didn’t sell the Sidekick. A key part of the Sidekick’s success started when T-Mobile brought out the red carpet for the launch of the color version of the device in 2003, during a Hollywood event before the X-Games. The launch party was a carousel of B-list celebrities and reality stars, including Lindsay Lohan, Paris Hilton, and Wilmer Valderrama, all showing up to claim their own Sidekick.

The phone became a constant presence on BET, MTV, UPN, and a ton of reality shows (DJ Quik used one on Method Man and Redman’s short-lived show, Method & Red). There was a star-studded TV commercial that featured Snoop Dogg, Paris Hilton, Burt Reynolds, and Wayne Newton using it. “Jennifer Aniston getting on TV and having the Sidekick ring in a purse, like, we didn’t give that to her, we didn’t pay her to do that,” Andy Rubin said. “That happened because it’s seeping to that demographic. So, if you can very carefully choose where you want your product to be visible then hopefully it can be successful.”

Impressionable teens were watching, and the Sidekick became the hot device to have. Soon teenage girls lucky enough to get one bedazzled their Sidekicks, and dudes slapped stickers on the backs of theirs. Teens carried Sidekicks around to show them off instead of keeping them in their pockets—technological jewelry. High-tech fashion was born.

While riding high, the Sidekick found its first scandal a year after the II’s release. Paris Hilton’s Sidekick was hacked through “social engineering”—a hacking method that involves getting information by manipulation. In Hilton’s case, it involved a hacker calling T-Mobile and tricking an employee into handing over her personal information. Because the Sidekick’s data was stored on the cloud, revealing pictures of hers were there for the taking, along with the phone numbers of her celebrity friends. “As soon as I went into her camera and saw nudes my head went JACKPOT,” one of the hackers told The Washington Post after the leaks. “I was like, HOLY **** DUDE... SHE’S GOT NUDES. THIS ****’S GONNA HIT THE PRESS SO ******* QUICK.”

It was one of the first major digital invasions of female celebrities' privacy, a spiritual descendant of the massive “Fappening” hacks in 2014, which targeted of celebrities’ iCloud accounts.

The Sidekick’s reputation didn’t take too much of a beating after the scandal, but around this time, competition was emerging. Andy Rubin left Danger and in 2003 co-founded Android, which Google bought in 2005. Android software paved Google’s way to taking over the mobile market in the early 2010s. At the same time, Apple was about a year into development on the iPhone. The Sidekick’s fate was basically sealed.

The Sidekick 3 launched in 2006, bundled with more applications and a trackpad that lit-up, which replaced the d-pad. T-Mobile weaved in celebrity marketing even more intimately by releasing three special edition models inspired by Diane von Fürstenberg, LRG, and Dwyane Wade (his was released in Feb. 2007, for the NBA All-Star Game). “[An ad for] the device covered the side of Mandalay Bay—one of the largest outdoor wallscapes in the U.S. at the time,” says Desmond Smith, a product manager at T-Mobile who worked with the company during the Sidekick’s heyday.

The Sidekick 3 launched in 2006, bundled with more applications and a trackpad that lit-up, which replaced the d-pad. T-Mobile weaved in celebrity marketing even more intimately by releasing three special edition models inspired by Diane von Fürstenberg, LRG, and Dwyane Wade (his was released in Feb. 2007, for the NBA All-Star Game). “[An ad for] the device covered the side of Mandalay Bay—one of the largest outdoor wallscapes in the U.S. at the time,” says Desmond Smith, a product manager at T-Mobile who worked with the company during the Sidekick’s heyday.

The Sidekick iD, a smaller and more affordable version of the 3, dropped in April 2007. To keep the price at a low $99, Sharp (the Sidekick’s manufacturer) removed a memory slot, Bluetooth features, and a 1.3-megapixel camera. The Sidekick LX was released the following October, the first Sidekick to be launched after the iPhone’s introduction in June of that year. While the keyboard and colorful display was praised, the phone’s large size and slow web-browsing speeds kept it from keeping up with the iPhone and BlackBerry Curve.

Microsoft bought Danger Inc. in Sept. 2008 for $500 million and had to steer the Sidekick brand through its second scandal.

In Oct. 2009, Microsoft was hit with a legendary outage that kept users from accessing their pictures, contacts, and other data. It wasn’t just a measly hour of downtime or anything like that: The outage lasted for almost a week, and some data didn’t return to users until late November. Celebrities who backed the phone soon turned against it. Users hit Microsoft with lawsuits for not having a backup plan for the outage—some cases weren’t settled until 2011.

The following year, with consumers throwing their cash toward the iPhone and Samsung Galaxy smartphones, Microsoft attempted to tap into the youth market the same way the Sidekick had a decade earlier. It released the Kin, a miniature Sidekick-inspired smartphone with a sliding keyboard that was tailored for teens who liked Facebook and Twitter. Two months after its release, it was discontinued. Smartphones like the iPhone were the new status symbols, and keyboards weren’t cool. Just ask Blackberry.

Devices that sold themselves on large keyboards soon gave way to phones with touchscreens and as many buttons as you have fingers on one hand. As the physical keyboard became less useful, the Sidekick brand went through its biggest change in 2010: T-Mobile announced that it was dropping Danger’s data service. So, Danger turned off its servers, and older Sidekicks that relied on their data centers were rendered useless. Then, Microsoft hit the reset button: All future Sidekicks were to run on Google’s Android OS, the same software that Sidekick co-founder Andy Rubin had developed. Things seemed to have come full circle, but not in a good way—this was the end of the line. Samsung’s Android-powered Sidekick 4G—released in April 2011—was the final Sidekick to leave factories before its discontinuation.

The Sidekick succeeded because it showed consumers how cool technology could be, that they could personalize a chunk of plastic and chips to make it their own, and ushered in an era of mobile computing for the masses. Say what you will about how fast its rising star burnt out, but the Sidekick is an important element in the link between cell phone and smartphone, technology and style.

What Danger and T-Mobile were able to do (whether it was intentional or not) was tap into something that Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine later did with their Beats headphones (and what Apple is attempting to do with the Apple Watch today) by making a device that's essential to one's personality and status, something stylish for the coming generation of consumers. The Sidekick wasn’t ever going to be able to compete with the likes of the iPhone and Samsung Galaxy, unless it morphed it something else entirely, but its features foreshadowed what was on the horizon. So many of us wanted an iPhone before we knew we wanted one because we saw the future of connectivity in the Sidekick.

In an era where new pieces of technology become obsolete by their first birthday, the Sidekick is, well, very much obsolete, but it has kept a lasting coolness about it that devices today lack. In the evolution of the mobile phone, the Sidekick has an important place (both in marketing and technology) in helping jumpstart the modern smartphone craze that would go into full effect at the end of the 2000s.

The device can still evoke nostalgia for those who owned one not only for its Internet capabilities, but for it being a pocket-sized canvas of expression during that slice of our lives when we were still coming into our own, whether it was decorating it with our high school colors, sticking our favorite team’s logo on it when they won the championship, or downloading the newest Jay Z track and making it our ringtone. While we grew, the technology grew with us. The Sidekick is very much a representation of the time and place in which it was popular. While whatever surviving Sidekicks left may be packed away somewhere in the garage, whenever one is rediscovered, we may look at it in the same fondness as once-embarrassing prom photos and high school love letters, if even for a moment.

It was a toy for those who thought they had given them up long ago.