Brian Harrington is an audio engineer and mixer that has worked in sessions across various recording studios in Los Angeles. He also runs his own music blog, Death By Algorithm.

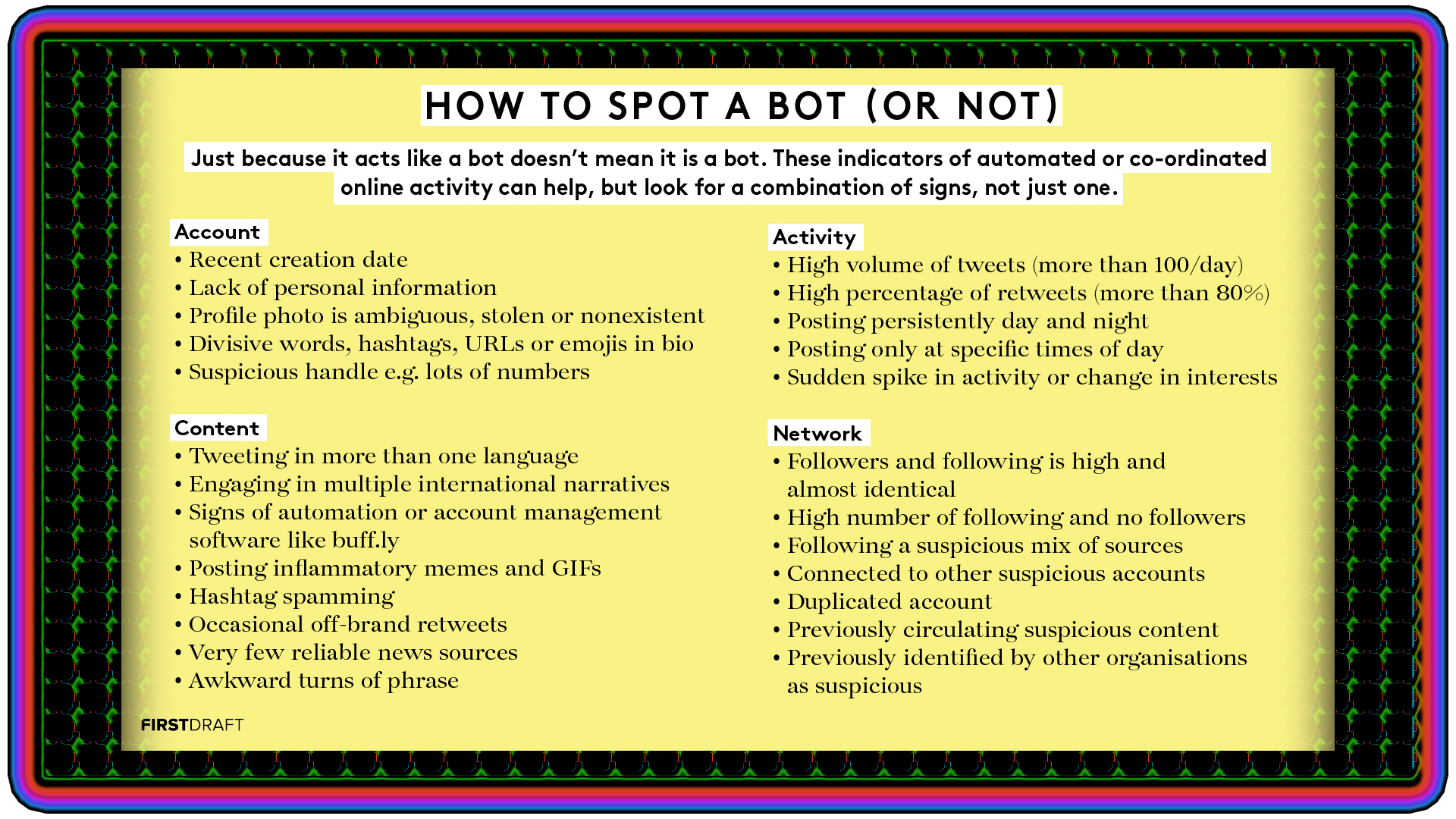

You may be internet savvy enough to spot when your latest Twitter follower is a bot, or recognize warning signs on a fake dating profile. But would you be able to recognize when an artist racking up streams is doing so fraudulently? It’s more common than you think.

Rolling Stone sources estimate that approximately three to four percent of all global streams are illegitimate, which would account for $300 million in lost revenue every year. While most digital streaming platforms have some form of fraud detection, there isn’t enough incentive to eliminate the problem entirely. Eric Drott, Professor at the University of Texas at Austin and author of the paper Fake Streams, Listening Bots, and Click Farms: Counterfeiting Attention in the Streaming Music Economy, found this in his research.

“There’s an economic rationality to allowing a certain amount of fraud to exist in any kind of economic system, because the costs of verifying every transaction would be so prohibitive,” Drott told me over Zoom. “Lost revenue” to bot streaming is only lost on the artists’ side, not on that of the streaming platforms. The DSPs will be making the same amount of money off of the subscription plan the bots use—or the ad space if they’re on a free tier—but it leaves less money on the table to pay out artists with a legitimate streaming base. “[Fraudulent Streaming] redistributes how the pot of money is getting divided, but it doesn’t change the size of the pot of money that Spotify is paying out to rights holders,” Drott explains.

Landing a high stream count or massive social media following can be very lucrative for jumpstarting an artist’s career—it can lead directly to label attention, playlist inclusion, press coverage, sync placements, and more. But for the fans, media, and others on the outskirts of the music industry, it can be a challenge to decipher if and how these numbers translate to actual offline interest.

“We see artists doing huge numbers on social media, hanging with Kardashians and whatnot, then they go on tour and struggle to fill a 200 capacity room in major markets,” says John O’Connor, booking agent for Songbyrd Music House in Washington DC. “I’d rather book an act that’s sold a room out on $10 tickets versus a new act with two million followers.” Many of the best shows O’Connor has booked have featured artists that had no major numbers behind their name yet, but knew how to rock a room and make those IRL connections.

T-Pain had an epiphany when he realized that most of the numbers he was chasing weren’t real. “I just love music again… I’m not chasing any numbers. I know these streams can be bought. I’m not getting that depression from Instagram anymore to where I’m like, ‘How the fuck are these little n****s doing this shit?’ I found out how they were doing it. Now you can see it every time,” T-Pain told Jessica McKinney for Complex. This understanding can also help fans identify what’s real and what’s artificial when looking at the numbers.

The truth can be difficult to spot and it’s nearly impossible to be 100% certain about anything, but there are some red flags and warning signs to look out for.

The Top Cities Don't Make Sense

Monthly listeners is an important metric, but it’s more of a passive count as it combines fans of the artist with people who listen to them unintentionally (playlists, another artist’s radio station, etc.). Spotify followers is an active count of users who intentionally engage with the artist by choosing to follow them. Because of the nature of these measurements, an artist is rarely going to have more followers than monthly listeners, but the fall off between the two will be much steeper if you’re faking stream numbers. What a “good” ratio looks like varies wildly, but in general the lower the better. Here are some examples for reference, from artists with strong, real fan bases of all sizes:

(Spotify Monthly Listeners) Artist: Monthly Listener to Followers ratio

(52M) Drake: 1 to 1

(20M) Kid Cudi: 4 to 1

(14.9M) Kehlani: 3 to 1

(10.5M) Charli XCX: 4 to 1

(3.7M) Freddie Gibbs: 5 to 1

(2.5M) Solange: 2 to 1

(2.1M) Saba: 5 to 1

(1.5M) KennyHoopla: 18 to 1

(1.1M) AG Club: 17 to 1

(992k) Tkay Maidza: 10 to 1

(779k) Deb Never: 16 to 1

(717k) Kenny Mason: 14 to 1

(562k) Nilüfer Yanya: 6 to 1

(483k) Redveil: 11 to 1

(406k) Jean Dawson: 9 to 1

(405k) María Isabel: 13 to 1

(321k) Grip: 23 to 1

(230k) The Blossom: 32 to 1

(212k) Jordana: 21 to 1

(209k) Baby Rose: 5 to 1

(206k) Paris Texas: 26 to 1

(160k) Fana Hues: 16 to 1

(150k) Liv.e: 7 to 1

(101k) Bartees Strange: 7 to 1

(94k) Raissa: 11 to 1

These are all good examples of what good, real Monthly Listener to Follower ratios can look like based on streaming base size. As you can see, it starts out with very small ratios, but there is more variation amongst smaller artists. Higher ratios become more common, especially once you get near that one million monthly listener mark and lower. That makes sense when you’re starting your career and only have a handful of songs out. 26 to 1 is a great ratio for a newcomer like Paris Texas, but would be less impressive for an artist of Drake’s stature. I crunched a lot of artist’s numbers for this table, and every example I ended up including represents a good ratio based on a Monthly Listener count that reflects legitimate offline fans and listeners, from artists that readers of P&P are likely to be familiar with.

Keep these reference ratios in mind when you’re questioning the numbers on an artist’s profile. A single digit ratio is very healthy, as is a low double digit ratio. And with artists around 1 million monthly listeners or less, anything below about 50 to 1 shouldn’t make you suspicious. Ratios significantly higher represent a large amount of streams with a minimal amount of active engagement on the listener’s end.

Suspicious Playlists

If an artist is placed on these suspicious playlists, streaming services will have terrible data for them. Most streaming platforms have some version of a “Fans Also Like” or “Related Artists” section on an artist’s page, and they fill this section using your data. When you listen to an artist, the algorithm sees what else you listen to, then it will compare that to what other fans are listening to, and take all that data together to find the artists that have the most listeners in common.

This typically works fine to put some overlapping artists onto the profile of anyone with a legitimate fanbase. But if you’re using bot streams, then the data is skewed towards what the bots are also streaming, which will be whoever else has paid those bots to stream their music or whatever random hits were also on the playlist the bots streamed. It’s unlikely that these artists will be related (genre wise) to the artist that paid for the streams. This throws off the algorithm and will fill an artist’s about section with completely unrelated data that should stand out as odd.

Social Media Followers are Primarily Bots

Donald Glover may be famous enough to have over three million Instagram followers without following anyone, but chances are an artist that you’re trying to gauge the hype on doesn’t have that luxury. Building an online following has to include engagement and interaction with fans, press, other artists, etc. on some level. Unless being “mysterious” and “reclusive” is a massive part of their image, an artist with five figure (or more!) followers versus double digit (or less!) following has some questions to answer about how they could possibly pull that off. Take notice too if they’re followed by anyone you recognize. Both Instagram and Twitter will tell you if a profile is followed by anyone you are following. This point is entirely dependent on your own social media, but if you follow artists and/or music industry people, then it might also be a red flag if a profile is “not followed by anyone you’re following.” If other artists you like, publications, or even just friends of yours follow someone, that gives you at least some proof they have a real following.

Fan Engagement is Lacking

One of the best ways to advance your career as a small artist is to make a splash in your local scene. If an artist is blowing up, it’s unlikely that no one in the local scene would know who they are. Search to see if they’ve done any hometown shows before. Check if they have any collaborations with local artists. The more support they have from the local scene, the more likely that they’ve been legitimately putting in work to build up a fanbase. That support can be as big as a sold out hometown show, or as simple as a local artist you recognize tweeting support for the artist.

And on the topic of collaborations, make sure that any features they have are legit. Spotify and third party sites that upload to Spotify don’t have the time or manpower to double check if every feature is real. So some artists have been able to game the system by saying they have high profile features on their songs when in reality they don’t. Wali Da Great is a known example of this. Listing much more famous artists like Blueface, Tay-K, and Lil Loaded as features (despite never working with them) allowed his songs to show up on those artist’s profiles. Once you listen, it becomes obvious that you’ve been fooled as the featured artist is not present, but you can’t take your stream back. Free advertising.

When you’re trying to figure out if an artist has a legitimate fanbase, never underestimate the old fashioned method: word of mouth. If you’ve made it to this point in the article, you probably care about music more than most, and (hopefully) have friends that do as well. Ask them if they’ve heard of an artist you’re curious about. And if so, how did they hear about them? Answers like “they were on my discover weekly” or “I let soundcloud autoplay and they came up” aren’t very helpful. Look for answers that prove an artist has been building a fanbase legitimately like “I saw them open at a concert I went to last year” or “they were featured on another artist’s album that I really like.” Anything that reveals some humanity behind the online numbers can help paint a clearer picture.

An easy way to see if word of mouth exists online: do a quick search on social media. Are there real people talking about this artist? If not, but they’ve still got millions of streams and a huge following, there’s a good chance something weird is going on.

A Case Study

Here’s an example of checking an artist’s Spotify profile and their socials for these red flags to see if they are inflating their numbers. In this case, there are a few things that don’t add up, and without exposing anyone, I’ll show you why I think so.

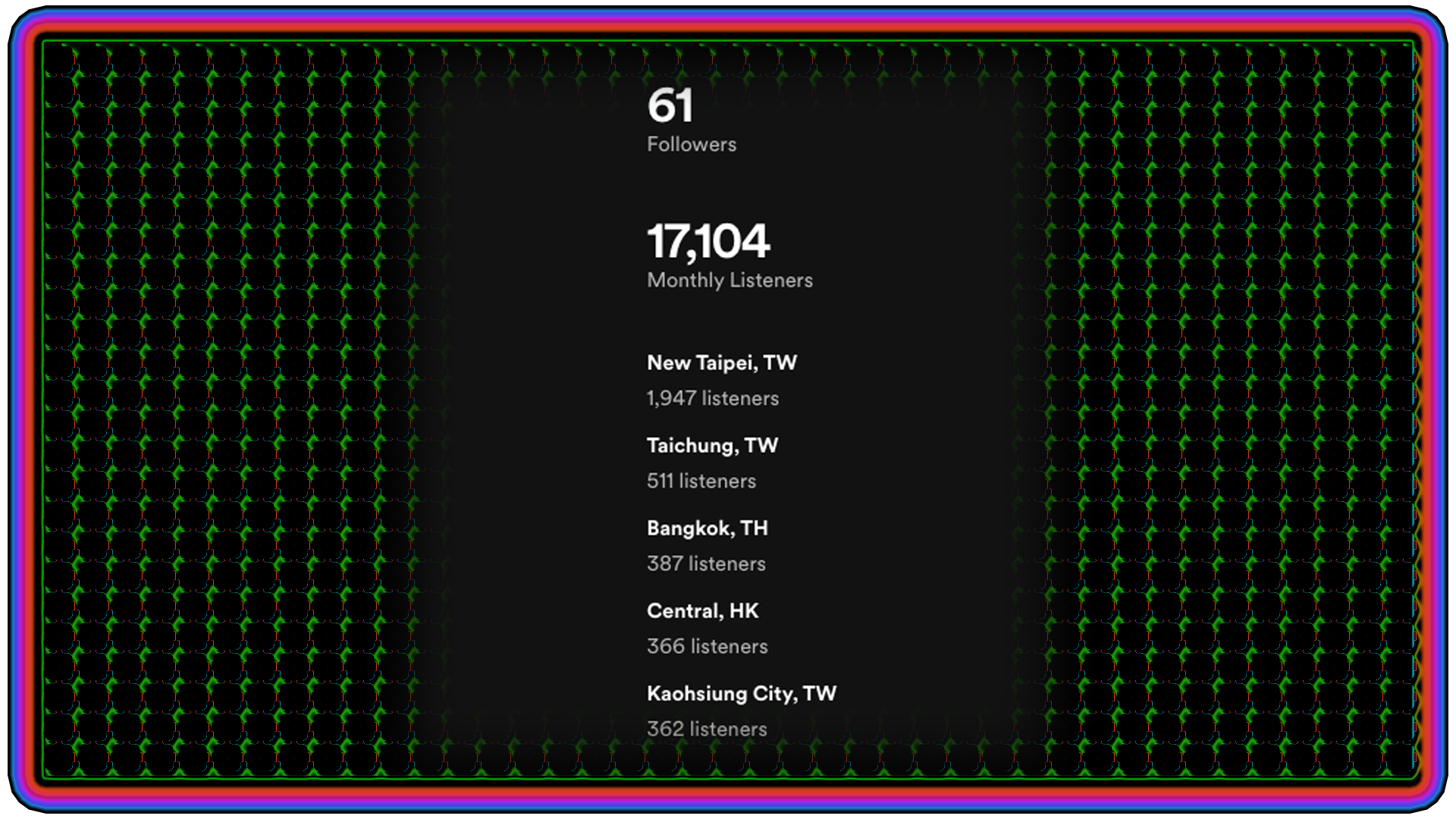

Streaming

This is an artist in Los Angeles who put out their first song in the beginning of April. Above are their Spotify stats after one week, in which the song saw just over 22,000 Spotify streams. The first sign I notice is not having a single US city in their top 5 despite being LA based, as well as the massive jump between Taichung and New Taipei, almost a 300% increase in listeners. The monthly listeners to followers ratio is 280 to 1. They are featured on some playlists that don’t match up to the status of a debut song by a new artist, or the sound of the song.

Some of the biggest playlists they are featured on have names related to global hit songs (the song is doing mildly well on streaming, but nowhere near enough to be considered a hit), surf music (most of the songs included, like our song in question, are not surf music), “Tick Tock Music 2020” (yes TikTok was spelled like that, no this song did not come out in 2020, and as of writing this only 11 TikTok videos have been made using the song, 7 of which are by the artist’s own account), and a classic rock playlist that by its own definition was only supposed to include tracks released prior to the 2000s. Many of these playlists have following counts in the hundreds of thousands.

I first discovered the song on SoundCloud, where the song has been putting up great numbers (over 80,000 plays). This is impressive for a debut song from an artist with only 115 followers on the platform. It could be achieved legitimately, but it’s impossible to tell for sure. SoundCloud doesn’t offer any insight outside of the numbers.

Socials

The about section of their Spotify links to their socials (Facebook, IG, and Twitter). Their Facebook page has one single like (A fascinating number. I know Facebook is not a popular tool for up and coming artists anymore, but if you’re going through the trouble of setting up a page, couldn’t you at least get all the people on your team to like it? Your parents? Anybody?). On Instagram, they have a large following, but the posts ranged from 2k-3k likes, and 50-250 comments.

The interactions on the posts feel legitimate but it’s low to the point that I think the followers number has been inflated by bots. Their twitter has just over 400 followers and very little interaction with each post.

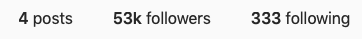

They have many tweets with 0 likes or retweets, and the others hover around 5 likes. Their pinned tweet about the song’s release (which racked up those 22k+ Spotify plays in just one week) got 4 likes, 2 retweets, and no replies. There’s clearly no bot activity going on with their Twitter, but it reinforces the idea that the IG followers have been inflated. Artists these days typically do have more followers on IG than Twitter, but 53k vs. 419 is a staggering dropoff, especially considering they seem to use both platforms at the same consistency.

On YouTube, they have 27 subscribers and 2 videos. Both videos are snippets, less than a minute long. One has a non-eyebrow raising 214 views, but the other has over 37,000 (similar to the Soundcloud numbers, this is unexpected, but not out of the realm of possibility). Under that video are 9 comments. One is by the label’s account, and another is by a fellow artist on the label. Of the other 7 comments, 4 of them are from accounts that were created on March 25th, 2021, just two days after the video’s release. These accounts have no profile image, no other information on their profile, and left a generic positive comment.

The music industry operates in strange ways, and any one of the points in this article could occur for an artist that is not using bots at all. There are numerous instances of Spotify yanking artists off their platform for data that their fraud detection software flags as illegitimate, when no bots were actually used. Even with all the red flags I pointed out in the case study, I can have my suspicions, but I can’t say definitively that the artist used bots on streaming or social media. Despite that, being wary of these red flags and looking out for multiple signs in succession will have you on your way towards being a smarter music consumer.

Using bots or click farms is rarely about getting money from the fake streams. Utilizing bots is about getting attention by faking attention until it turns into real attention. In some ways it’s not that different from Soulja Boy uploading his songs to Limewire disguised as a hit song. In fact, Drott pointed out that attention-faking has existed in nearly all forms of entertainment dating back to the 19th century. “Claques,” the name given to people paid to loudly applaud performers at the French grand opera, are the first known example.

If this information scares you, the best thing to do is not give these artists your attention, whether that attention is positive or negative. Because while using bots and scams to generate fake hype may help some artists skip steps on their way to fame, it ultimately takes away attention, streams, and money from artists trying to build a fanbase honestly.