In 2010, Jamie Oborne was almost certain that the scrappy Manchester band he was managing, The 1975, was going to get a major label deal. At least, that’s the way the band’s frontman Matthew Healy tells the story to me over FaceTime. “Every single record label came out to hear us play,” Healy says, calling from a hotel room in Philadelphia. “And they all passed on it, because they didn't really get it.”

After seeing how depressed Healy was getting from all the rejections, Oborne floated an idea to the band that December. Along with The 1975, he wanted to start his own independent label called Dirty Hit, which would operate in tandem with his All On Red management company. The goal was for his artists to be able to build a platform for themselves when no one was offering to support them. The 1975 agreed and signed to their own label for 20 pounds.

Since then, The 1975 have hooked an international fanbase of millions with ambitiously philosophical, yet endlessly catchy synth-pop and rock. Earlier this year, they won the two most prestigious BRIT awards—Best British Group and Best British Album—for their most recent full-length, 2018’s A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships. And because they’ve operated under their own label this whole time, they’ve been able to maintain total creative freedom.

In the past near-decade since it was founded, Dirty Hit has become known for championing their artists’ individuality and has facilitated the launch of nearly two dozen artists, from mainstays Wolf Alice (who won the 2018 Mercury Prize) to more recent signees like rising artists No Rome and Beabadoobee. Last year, Oborne was recognized as the Entrepreneur of the Year at the 2018 Artist & Manager Awards for Dirty Hit’s unflinching commitment to artistic integrity.

When I ask Oborne how he’s brought Dirty Hit to such prominence, he explains how he runs a record label as if it’s common sense. “My approach to A&R is that I think artists are right 90% of the time,” the 45-year-old entrepreneur says, talking in a slow, somber voice that sounds simultaneously wise and lackadaisical. “And I think sometimes other people in the A&R community, they view it the opposite, where they think the artist is wrong 90% of the time.” His mission in running the label is also the same, as when he first started it. “I’m just trying to work with the artists that I love and market them in an interesting and new way,” he says. “I guess our main goal is to leave a legacy that we’ve shaped culture in some way.”

What kind of things are Dirty Hit looking for in a potential signee? “A unique voice,” Oborne says. “I really want to hear something with meaning… I don’t necessarily mean that it has to have a socio-political message, but at least that artist is trying to make a statement with their songs.”

It’s not just that Dirty Hit lets their artists do whatever they want. In our short conversation, it becomes very clear that Oborne cares deeply about establishing a rapport with his artists that goes beyond publicity. When he speaks of his dynamic with Healy, Oborne’s voice takes on a warm tone, as if he was speaking of a younger brother rather than a business partner. “We very seldom disagree on things and when we do, we take each other’s opinions so seriously the other one usually drops it. That’s what happens after two decades of working with someone.”

“I try and show people, you can be one of the biggest bands in the world and not give a f*ck about any rules. I think what Dirty Hit refuses to do is patronize its audience." - Matty healy

As Dirty Hit’s creative director, Healy claims that the success of The 1975 is proof that the label’s philosophy actually works. “I try and show people, you can be one of the biggest bands in the world and not give a fuck about any rules,” Healy says. “I think what Dirty Hit refuses to do is patronize its audience, and that's what I love about it. There's so many references to high art, poetry, literature, and it’s huge. It understands that kids are smart, and they're going to get the joke or reference.” Throughout the band’s career, they’ve been increasingly vocal about misogyny in the music industry, LGBTQ+ issues, the climate crisis, British and American imperialism, and Healy’s own former heroin addiction. When I ask if there was any pushback from his management or label when The 1975 wanted to feature environmental activist Greta Thunberg on the first single of their upcoming new album, Healy appeared genuinely confused. “Pushback? There is no place to get pushback from.”

Dirty Hit’s approach is refreshing, considering the continual horror stories from artists about the exploitative major label contracts they’ve entered that merely stifle their creative vision. Currently, Taylor Swift is undergoing a public battle over the ownership of her songs and recordings with her ex-label boss Scott Borchetta and prominent music manager Scooter Braun. Earlier this year, Tinashe was released from her record deal with RCA, following years of her hinting that they often undermined her autonomy. (In a recent tweet, she wrote that her label always “sabotaged her real art.”) After leaving Def Jam a couple years ago, Frank Ocean spoke about how oppressive the industry can be, in general, in a Gayletter interview: “Well, fucking with major music companies, you’re going to be… deflowered. Anytime you get into the business side of the arts, there has to be some degree of objectification or commodification that you’re comfortable with, of yourself and of your work.”

Oborne also spoke to how The 1975’s path inspired the latest generation of artists, who are drawn to Dirty Hit. “I think the whole bedroom pop scene is indebted to The 1975,” Oborne said. “They’ve inspired more kids to be more creative to work with what they have, self-producing. They’ve been such advocates of controlling their creative expression and conveying a sharp sense of reality in the narrative of their work. They’ve inspired lots of young artists to not accept rules that people in the media try to impose upon them.”

No Rome, a Filipino-British R&B artist who signed to Dirty Hit in 2017, says that the label’s philosophy was clear just from the initial conversations he had with them. “When I was on the phone speaking with labels at the time, some of them didn't entirely agree with me tackling this idea of being an ‘audio-visual’ artist,” Rome writes in an email. “When I was speaking with Dirty Hit on a phone call, they said, ‘Yes, we love that idea.’ They saw potential in what I wanted to do.”

And like many other artist-centric labels or imprints—like Drake’s OVO Sound, Kendrick Lamar’s TDE, Kanye West’s G.O.O.D. Music, or J. Cole’s Dreamville—many of the newer artists on Dirty Hit’s roster can benefit in multiple ways from being in the same orbit as The 1975. The band has taken several of their labelmates on tour as their openers, including Wolf Alice (a British alt-rock band), Pale Waves (a British dark synth-pop band), the Japanese House (the dream pop solo act of Amber Bain), and No Rome, for his first-ever tour. Healy and The 1975’s drummer/producer George Daniel have also helped produce projects by the Japanese House and No Rome, with plans to help Beabadoobee (a 19-year-old grunge-y rock singer-songwriter that signed to Dirty Hit in 2018) produce an album when she joins The 1975 on tour in February.

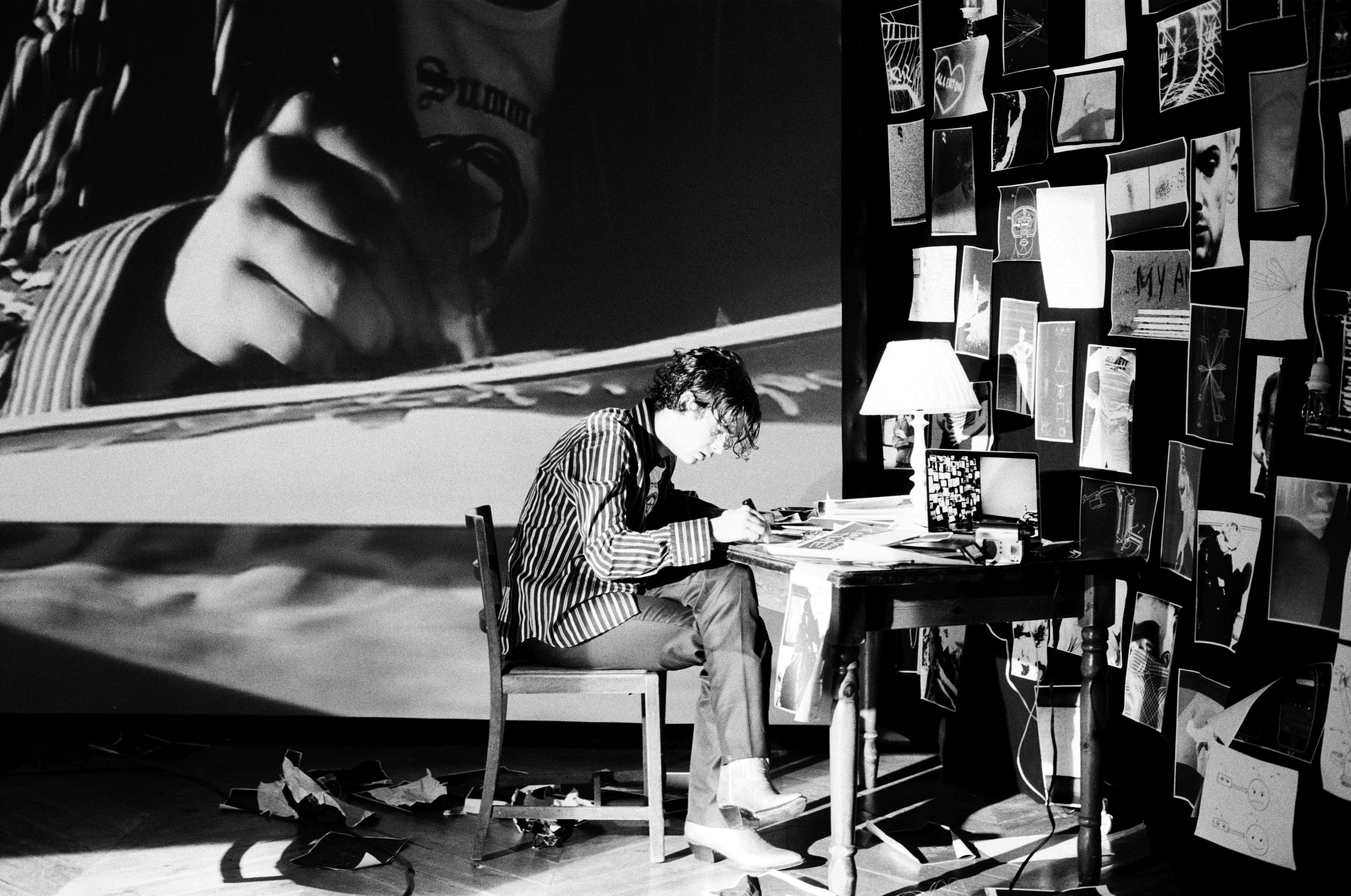

Specifically, Healy is also a large part of the appeal for joining the label. Through being The 1975’s frontman, he’s become his own icon, partly due to his bold (and sometimes controversial) opinions, partly due to his perpetual teen heartthrob status, and partly due to his sharp aesthetic eye when it comes to pairing visuals with music. And when he’s working with the Dirty Hit artists he’s signed, he uses his experience to help others build the same confidence that he’s achieved throughout the years. “I just try to show young artists what they're capable of,” Healy says. “But the best thing about Dirty Hit is [all the artists are] just a bunch of creative directors. You don't need to tell them what to do. I answer them when they ask me questions, I'm just there.”

Though he downplays his own duties, Healy’s become as a mentor to the artists he looks after, which can extend in meaning as far as inviting Rome to come and live in his house, coaching him in the studio while making his debut RIP Indo Hisashi EP, and sending Bea “a new song to kind of get excited about” every day while she’s on tour. The reason that Healy’s so involved, he admits, is because he’s type of music fan who gets excited about innovative and boundary-pushing artists.

In response, these young artists say that they feel inspired. “Having George Daniel and Matty co-produce my first two studio EPs helped me see my music from a new perspective,” Rome writes. “Exchanging ideas with Matty and trading inspirations—you learn [a lot from] a person when you spend loads of time with them, and I think that’s what happened.” Bea is in agreement. When I ask her what she thinks of the Dirty Hit team and The 1975, she writes: “[They’re] all so lovely, supportive, and cool as fuck... I’m very glad to be a part of their lives.”

Besides Rome and Bea, the label has added a handful of new signees within the past year or so, like the 18-year-old self-produced indie singer-songwriter Oscar Lang and the rowdy London rock quarter King Nun. The roster has also gotten noticeably more diverse, with the addition of Dirty Hit’s first rap acts, including Virginia rapper Caleb Steph and South London lo-fi hip-hop group 404. And there’s also the 19-year-old R&B singer AMA, queer pop artist Gia Ford, and the Japanese-English singer Rina Sawayama, who debuted on Dirty Hit just last month with a completely exhilerating nü-metal sound. Healy assures me that there’s even more on the way, telling me that Dirty Hit is gearing up to sign another young British R&B singer named Kasai and a singer-rapper named Boy Band, who has a collaboration with Good Charlotte in the works. Healy chatters excitedly about these artists, admiring how they’re each honoring their own authenticity. “I'm very lucky to be so involved in so many amazing artists that I really believe in. It's kind of a dream of mine, you know?”

And of course, Dirty Hit is gearing up to release The 1975’s fourth studio album, Notes on a Conditional Form, set for release on February 21, 2020. When I ask Healy how finished the album is when we speak in mid-November, he says it’s “70%” finished, with two pesky songs that “have fucking haunted” him for years. There’s one in particular, called “What Should I Say” that Healy thinks could be the band’s biggest song yet, but he hasn’t finished it and has only kept working on it due to Jamie’s insistence. “To be fair, the last two times Jamie pushed me to finish a song, it was ‘Sex’ and ‘Love it If We Made It,’” Healy says. He also says that the project will include contributions from Bea, Rome, and the Japanese House’s Amber Bain will appear on the project, as well as a feature from Phoebe Bridgers.

"A really important part of it is the notion that our culture and our artists are always moving forward." - Jamie oborne

Before he gets off the phone, Healy also tells me about a couple of other projects he has floating around in his head, like a soundtrack that he wants to make after he gets off tour and, perhaps, a documentary on The 1975. “We filmed pretty much everything since we were 17,” Healy says. “Honestly, we have the documentation to end all documentations. But, for me, I never wanted to make one that was about a specific time. I want it to be a full thing, and that's a retrospective statement… Our band's always been so moving forward that I've never really wanted to look back.”

Oborne says something similar about how Dirty Hit’s rapid expansion is just the obvious next step for the company. “As we get better at what we do, and our artists get bigger, we seem to attract other artists that also want to be part of our culture,” he explains. “A really important part of it is the notion that our culture and our artists are always moving forward.” Oborne and The 1975 have built their own label from the ground up, by forging ahead of trends for nearly a decade. They feel like they can’t stop now.