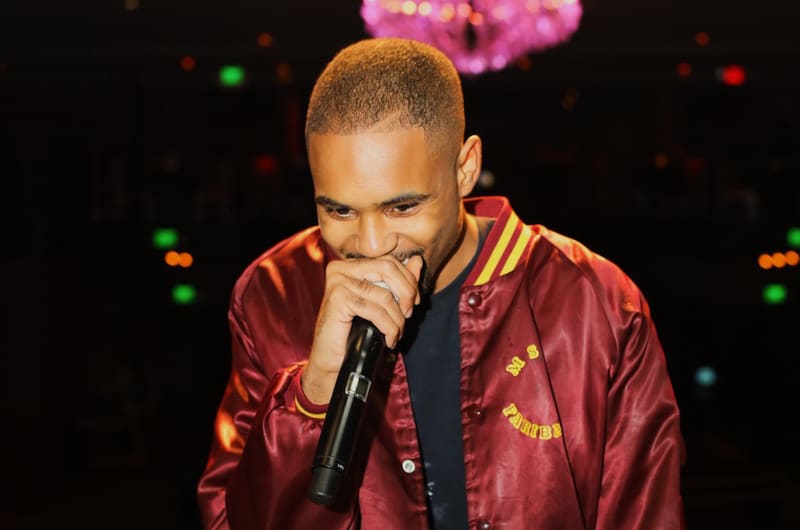

There’s a quiet intensity to Quadry’s music, sometimes masked by his lilting delivery. If you didn’t understand the words, you might guess he’s singing about girls and summer. And while those songs do exist in the Baton Rouge rapper’s catalog, he has more important things to say. “It’s so American here,” Quadry says of his hometown. “It’s segregated, there are so many weapons. It’s a test tube of America.”

He was a quiet kid growing up in Baker, a sleepy, swampy neighborhood on the north end of East Baton Rouge Parish. “My relatives say it was like I was here before,” he says. “I would say quick-witted comebacks to adults that would make them say, ‘Yo, that was kind of clever.’”

Living as a creative was already feeling a foregone conclusion—Quadry was rapping before his tenth birthday. “Say this is my ninth life,” he says. “I feel like in every life, I was an artist... In the Renaissance, even caveman times. I was always an artist.”

He was making the discovery in a changed Baton Rouge. Things shifted when Hurricane Katrina devastated low-lying New Orleans in 2005. “I was ten, I was in fifth grade.” Quadry remembers. “Baton Rouge didn’t get hit as hard as New Orleans—Baton Rouge was okay. But it made a population of people from New Orleans integrate into Baton Rouge. We got their style, their slang, the way they act. That seeped into our rapping, too.”

Hurricane Katrina was really pivotal. It made a population of people from New Orleans integrate into Baton Rouge. So we got their style, their slang, the way they act.

The transplanted culture exposed a young Quadry to artists like Lil Wayne and Master P. As he grew older, Quadry had established himself online as an exciting, agile rapper with early hits like the 2014 Mr. Carmack collaboration “Monday.” He built digital connections with then-unknowns like Romil and Tev’n, the North London producer who would end up producing six tracks on Quadry’s debut project, America, Me. “He can really paint a picture,” Tev’n said over the phone. “His lyrics are so vivid. You can almost touch what he’s saying... All the music is really just a backdrop for his stories. That’s what I noticed about his stuff originally, and I thought, 'Oh man, I gotta step my game up.'”

One week before America, Me went public, Alton Sterling was killed by police outside the Triple S Food Mart in Baton Rouge. “I grew up in that neighborhood,” Quadry says. His family moved to Baker when he was seven. “I used to go to that store for Rice Krispies Treats every Saturday. To have that happen was a shock to my youth… You get colder. But that’s just America. That’s all it is.”

America, Me had released a week later as planned, with much of its content and emotional depth suddenly brought into sharp focus against the backdrop of Sterling’s death and the city’s growing protest movement. Quadry’s name began to circulate locally, and he gained acclaim on blogs. But it was the artist’s own intuition that led to the next step.

Brock Korsan built a career working with the likes of Kendrick Lamar, ScHoolboy Q, and DJ Dahi. He met Quadry on Twitter, when the rapper replied to Korsan’s open call for submissions. “I was leaving an A&R meeting at Def Jam, and I was very dejected,” Korsan says. “I felt like everything was changing, and I just went on Twitter—which I rarely do, in terms of searching for new music. And I basically said, 'Is there anyone out there feeling overlooked and underappreciated?'

I got like a million replies, and Quadry had put the woman-raising-her-hand emoji, and a link. I just started laughing, I thought it was hilarious. The first song was his 'Pony' flip, and I was like, 'This song is fucking terrible, but the guy can rap.' The next song was 'Monday,' and I thought it was genius. The way he was putting words together, he reminded me of Andre [3000].”

Korsan flew Quadry out to L.A., where he met longtime collaborator Tev’n in person for the first time. Over the next two weeks, Quadry put in time to finish the album now known as Malik Ruff. “I stayed at the studio for 12 days,” Tev’n says. “That was the first time [Quadry and I] actually met, but we felt like we already knew each other after talking every day for so long… He’s really easy to talk to, and he’s a good listener. That’s probably why he’s such a good writer as well, he just takes everything in.”

“Initially, I spent a lot of time with him in the studio,” Korsan says. “But after a while, I realized he’s just gotta figure out his thing. For as level-headed as Quadry is, he’s also very headstrong. I just said, ‘I’m going to give you the space, you can use this space as much as you want,’ and we started the journey. He knows what he wants to do, and he has a vision, and he’s usually correct. We’ll be on the fence about things, and when he come back to it I’ll say, ‘You were right about that.’”

Malik Ruff was released in November 2018 and the world it lives in is Southern hospitality surrounded by shadowy death, where Boosie shares space with Pink Floyd. The album was met with critical acclaim, and has endured a “slow burn” since, as Korsan put it. “I feel like he knows that he’s one of the best rappers out there, pound for pound. And he’s ready for people to see that. When I found him, he was working at McDonalds. To see everyone react like this—I get texts from some of the biggest artists in the world saying this kid’s amazing.”

Quadry is taking all the access in stride. “You know in The Wizard of Oz, when they pull back the curtain and found out it was just a man? Before, when I was a fan and listening to albums like good kid m.A.A.d city, Friday Night Lights, or Take Care, I thought those guys were making magic. I thought maybe they were taking some kind of drug, something I didn’t have enough money to do or wasn’t old enough to do. Now I’ve learned... all that was preparation, work ethic, and stimulation, like reading. One thing that Brock showed me was that it’s not magic. It’s just voice and talent. If you work hard enough at it, you’ll be one of the best at it.”

Congratulations on “bluegrass” getting played on Beats 1 last night.

Thank you bro, I didn’t even hear it! I don’t know why I didn’t want to hear it. You know what it was? I had to do the selfie video, I had to do all types of stuff, and it kind of took the mystique out of it. That was cool, though. It’s a milestone. Word of mouth has been the number one form of discovery for my music. Pigeons & Planes had gone on hiatus so I was trying to figure out other ways to get my music to publications. You guys were like the main people that were really pushing my music. Word of mouth took over from there.

What’s the story behind the album title?

At first, Malik Ruff was called Black Boy Machine Gun. That was the first title of the album. This is early 2016, after I dropped America, Me. I wanted to make an album about my experiences, but not from a first-person point of view. Malik Ruff was meant to be a pseudonym—this is black male angst on the record, that’s the best way I can describe it.

That has some echoes to America, Me, as well. What was the difference in your approach to this album?

The first tape was basically me and Tev’n. Shout out Ricci Riera and Chuck Strangers who worked on America, Me too. But the big difference for Malik Ruff was that I wanted R&B singers to produce the rap songs on there. I got Steve [Lacy], bLAck pARty, even with Tev’n—it’s in a way more R&B, melodic range. I wanted to bring in guys who had a strong grasp of song structure and writing. Making the songs more full, and the ideas more fleshed out. We were building almost all of those beats from scratch, so they transformed into what they are now. With America, Me, all of those beats were made just like that and I rapped on them.

Did you always go by Quadry, as an artist?

I was called Lil Quad, but we say it how we spell it, so it was Lit Quad. That was before “lit” had came about. I was 14, 15, just trying to get better at rapping.

What’s it like coming back to Baton Rouge now that you’ve lived somewhere else?

I still go back a little bit. It’s not sad because everybody knows what I’m out here to do. It’s not a sadness… the sadness comes when I’m out in L.A., and I’m just reminiscing on times. Other than that, as far as leaving, everybody at home is all for it.

How have you seen the city change recently, as far as a music scene is concerned?

I don’t want to say we’re on the map like a Memphis or Atlanta. To be honest, Baton Rouge rap hasn’t even been around for all that long. Maybe ‘99, at the earliest. I feel like we’re still changing—look at the powerhouse that’s right next to us, in Houston. That was going back in ‘86, with the Geto Boys. That gave way to Screw’s music, then UGK. And then after that is the explosion, with the Slim Thugs and Paul Walls.

I think Baton Rouge as a city, in the rap game, we’re in that mid-stage. We’ve had national stars, Kevin Gates and all that, but that’s just one side of the coin. Baton Rouge has never had, to my limited knowledge, a Dungeon Family type of thing. That’s the thing that’s changing now, since 2015 or 2016. The lyricists are starting to see themselves as lyricists.

What do you mean by mid-stage? That rap didn’t really take hold in Baton Rouge until the mid-’90s?

Late ‘90s, really, with the Young Bleed and Master P joint “How Ya Do Dat.” But for my generation of rhymers and rappers, Hurricane Katrina was really pivotal. It made a population of people from New Orleans integrate into Baton Rouge. So we got their style, their slang, the way they act. That seeped into our rapping, too.

What did Katrina look like for you, how old were you when it happened?

I was ten, I was in elementary school. Fifth grade. Baton Rouge didn’t get hit as hard as New Orleans—you gotta understand, Baton Rouge is kind of elevated. The real force of the hurricane hit coastal, up into the Gulf. New Orleans is an underwater city, really. Baton Rouge was okay. But the attitude, that seeped into Baton Rouge.

The one thing I want for my city is for people to care about where each of our artists is actually from, in terms of a neighborhood. I’m from Baker, it’s a different vibe from where NBA Youngboy is from. I want people to understand that this is a real specific place where we come from. Baker is at the tip-top of the north side of Baton Rouge. If you’re in Baton Rouge, you don’t really consider Baker a part of the city, because it’s so far north. It’s past Southern University, it’s past Scotlandville. It’s the last black neighborhood before you get into the countryside.

It’s also three blocks away from where Alton Sterling was killed. I grew up in that neighborhood, I used to go to that store for Rice Krispies Treats every Saturday. I knew that store, and to have that happen was a shock to my youth. When you’re young, you have those rose-tinted glasses and you see things in the most optimistic way. You see a drug addict as a sick man. "Oh, he’s just sick." But when you get older, you can see he’s a fiend. You get colder. But it’s just America. That’s all that is. And where I’m from is no different than anywhere else. That’s why I think rappers from here relate so good, it’s so America here. It’s segregated, there are so many weapons. It’s a test tube of America.

that’s why I think rappers from here relate so good, it’s so America here. It’s segregated, there are so many weapons. It’s a test tube of America.

Do you think people in Baton Rouge have any hope that things are getting better? Sterling’s killers walked free, but that cop was convicted in Chicago recently.

It started because people wanted to catch the moment. “Worldstar!” You see what I’m saying? And that led to these acts being caught on camera and posted. I don’t know how many times I’ve seen an incident like that on somebody’s phone that never made the internet. I’m talking 2010, 2011. Seeing somebody getting slammed, beat up by police. The advent of social media kind of made it that.

But things can get better when people start taking accountability. South Africa had the reconciliation, and black people in America can’t even get their case heard for reparations. And I’m not saying just white people take responsibility. Black people can take responsibility too. We have some soul-searching to do in America. Exclude everybody else for a second and focus on ourselves, and then we can flourish as the people we are meant to be in this country.

And it has to start in multiple places at once, not just criminal justice reform.

I’m thinking about the whole shebangabang, where my son can walk into any establishment and be seen as equal, as a man. We can wash away the laws with a flick of the pen, but when I have my hair nappy—sometimes I don’t cut my hair for a few months, and I grow a beard, and when I’m in California, there are places where I get looks like a dog that’s off the leash. We have to nick at that too. It’s about having empathy.

There’s a lot of that on Malik Ruff. Can you talk about “Bible in the Water?”

You can interpret it how you want. It could be interpreted as an indictment on religion, but Tev’n just came in and sung that hook, and I took that. The reason I found it intriguing was the whole thought of a bible in the water—something so sacred, something so close to your heart, is being destroyed in water, but the water moving constantly. I saw it as a metaphor. You can’t be stagnant in your thoughts and your beliefs, you have to flow with the water.

Do you believe in reincarnation, or anything like that?

I don’t believe in the kind of reincarnation where certain historical figures carry on—like, I don’t think Napoleon came back as a baby in South Detroit, or Michael Jackson is a baby in Germany. But I do believe that certain energies carry throughout time. Certain essences. Say this is my ninth life. I feel like in every life, I was an artist, of the zeitgeist of any period. In the Renaissance, even caveman times. I was always an artist.

That’s something I thought about when I heard “Wesley (For My Son),” when you were writing from your father’s perspective so soon after he passed.

I can tell you exactly the day I wrote it. I had the beat for a while, at least two weeks before. But when we went to the studio and I heard it again, all those emotions started flowing out of me—what I wanted to say, what I needed to say—even that concept of speaking from my dad’s perspective came in five, ten minutes. It was one of the one times I really felt like God was in the studio, guiding my hand. I cried while I was writing it, turned off all the lights because I didn’t want anyone to see me cry. I learned a lot about being a man when I was making this album. I learned it’s okay to be vulnerable, it’s okay to have feelings and express them. Not try to push them down—that can lead to something really destructive.

Are there any sessions that stand out?

When I recorded the first verse of “Bluegrass,” Romil played me that beat a week before I recorded it. As I remember—I don’t think he had any intentions of guiding me through the recording, but he came back for another session four days after showing me the beat. I rapped the verse I had written, and after Romil heard it he said, “Hey, why don’t you chop up the lines? Take a pause between the lines.” And I said, “YO! Okay!” It’s like we both found our wings then, because mind you, this is before [Brockhampton] had even started on Saturation. We were just in there, turned off all the lights—Jabari was there too—and Romil is just coaching me through the verses. I could see him just loving that, reveling in that. And I was too, I want to be coached by a great producer. That’s one of the reasons I do it, and Romil’s one of the best people I’ve ever met.

That’s the best, when something gets created that none of the individuals could have done on their own.

And that’s kind of the story of Malik. I’m the auteur, and I’m holding the reins, but it was a team effort. From the sounds to the lyrics to the arrangement of the songs, everybody had an equal input. And that’s how I wanted it.

How did you first meet Romil?

It was back when people would just put their numbers on Twitter, and have their fans talk to them, around 2014. Romil put his number on Twitter and said, “Anybody text me.” I texted him and asked who was better, Mannie Fresh or Pharrell. He said Pharrell, which just led into a whole argument about legacies. Then I just kept him updated on what Tev’n and I were doing. Then I sent Brock my music that same year. 2015 was a pivotal year for me. Then in 2016 I dropped America, Me, so by the time I started making Malik Ruff I had enough of a caché to ask Romil if he wanted to work.

It definitely feels like you’re taking on a lot more on Malik Ruff, both from an emotional and production standpoint. How much of that had to do with working with Brock [Korsan]?

You know in The Wizard of Oz, when they pull back the curtain and found out it was just a man? Before, when I was a fan and listening to albums like good kid m.A.A.d city, Friday Night Lights, or Take Care, I thought those guys were making magic. I thought maybe they were taking some kind of drug, something I didn’t have enough money to do or wasn’t old enough to do.

Now I’ve learned, since working with Brock, all that was preparation, work ethic, and stimulation, like reading. One thing that Brock showed me was that it’s not magic. It’s just voice and talent. If you work hard enough at it, you’ll be one of the best at it. No cap. If I work hard at it, I’ll be one of the best rappers.

What were you watching or reading during the making of Malik Ruff?

There’s a movie on Netflix now called Dayveon—it’s about a 13-year-old living in small town Arkansas, and it matched Malik Ruff so well. The crickets on the end of “Wesley,” especially—if Malik Ruff is the music, Dayveon is the film. From watching that film—I had a lot of the songs done, but Dayveon just confirmed my concept. Real issues that young black men go through, like depression. There’s just a litany of things that Dayveon deals with, with no sensationalism. In the movie, his older brother dies and he’s depressed. He doesn’t even know he’s depressed, he’s just angry all the time. He gets involved with a gang out of pure boredom, in small-town Arkansas.

Was there a specific moment where you realized music could be a career?

I’ve been thinking about it like this. I don’t know if this is me being a douchebag, but I had a conversation with Kendrick Lamar at this breakfast spot in L.A. I just followed him inside and took a chance—I wanted to get a burger anyway. We had spoken before, and afterwards Brock said Kendrick mentioned I had a good personality, and if I could just let people see that, the world would open up for me. So with press, that’s really all I want to do, really. I’m not trying to hide anything, I’m not trying to sugarcoat nothing. I’m not trying to do a bait and switch, I’m just trying to show people who I am. If they like it, I love them. If they don’t, fuck ‘em.

What’d you and Kendrick talk about in the breakfast spot?

He asked me if Baton Rouge had any beaches [Laughs]. I told him kind of—more like riverbanks. And he just shook his head like, “Oh, nah.” He just asked me how everything was going, where the music was going. Mind you, this was before Malik Ruff. I was telling him the ideas about it, how I wanted R&B singers to produce it. He was just telling me to follow whatever I had in my mind. I asked him how he approaches projects: does he have 80% planned out or just let it happen in the studio, and he said he has it all planned out before he goes in. That chipped my ego a little bit, because I had been going into the studio and just working it out.