From the benches in the flower garden of Kennington Park, south London—not far from The London Eye and Houses of Parliament—you can see people reading books, jogging, and walking their dogs. The nearby road is lined with cozy townhouses and gastropubs, and in summer, the buzz of crowds at Oval cricket ground echoes between buildings.

Sounds lovely, doesn’t it? The deceptive thing about life in London, though, is that pleasant vignettes are never far from harsher realities. Kennington is known in professional circles as the home of politicians and diplomats, and neighboring towns of Brixton, Peckham, and Elephant & Castle as trendy, regenerated hubs of restaurants and bars. But among local teenagers, these areas have a very different reputation. In recent years South London has been the epicenter of the next generation’s sonic earthquake. Comparable to the conception of grime in East London at the start of the millennium, UK drill music has shaken the foundations of British youth culture.

“Fuck Trident, we all violent, man back your city,” spits MizOrMac, a member of the drill collective Harlem Spartans, in the chorus of “Kent Nizzy.” The Spartans are local celebrities who have stacked up millions of YouTube views over the last 18 months, and they live in Kennington Park Estate, a social housing complex wedged between the park and historic cricket stadium. This particular line is referring to Operation Trident: the London Metropolitan policing initiative established in 1998 to reduce gang-violence after a series of fatal shootings. “Kennington where it’s fucking sticky!” goes the next. If you listen to enough of these lyrics, you would be inclined to believe him.

Drill music—the breed of trap-rap conceived on the streets of Chicago at the start of this decade—has not just arrived in London: it is taking over the underground scene. Videos of Chief Keef and drill’s other key artists landed in London via YouTube in 2012. The English capital’s most impoverished pockets south of the River Thames proved fertile turf for the genre’s digital cross-pollination. By late-2014, MCs in Brixton—the gentrifying heartland of London’s Caribbean diaspora—were gaining online attention for their videos of raps over trappy, American-style instrumentals, such as 67 (pronounced “six-seven”) frontman LD’s “Live Corn” and 150’s (“one-fiddy”) Jamaican patois-tinged “Look Like You.” Fast-forward to 2018, however, and the sound has evolved beyond its Windy City roots.

In its production, UK drill has transformed to match its new environment. It employs diverse melodies—delicate like Carns Hill and Papi’s “Run With The Runners,” ethereal like M1onthebeat, MK The Plug, and CB’s “Take That Risk,” synth-laden like Fumez The Engineer’s “Round Here”—which offset an oscillating bass that swings, thumps, and shudders like a double decker bus. The music’s speed has moved closer to grime’s mark of 140 beats-per-minute, shown most explicitly by BT, Rendo, and V.I.’s “PM to the AM.” And its lyrics—which barely stray from the topics of illicit drug economics, territorial pride, misogynistic showboating, and weapon-wielding violence—reflect the reality for the artists writing them. Poetic social commentary does appear, squeezed between otherwise brutal, unforgiving content, like a rose growing from worn concrete. In his booming voice, AM in “Jump That Fence” states: “Broken hearts, broken phones, diligent yutes from broken homes.”

To be clear, themes discussed by drill artists are not a million miles away from those that have been featured at the grittiest end of grime, or in the music of British road-rappers like Giggs, Skrapz, or K Koke. But drill is dragging the character of British music into uncharted depths of cultural subterranea. Take knives as a topical example. In its wilder formative years, a grime verse or freestyle from artists like Trim or D Double E might refer to weapons and the act of stabbing someone.

Now, a significant number of UK drill artists discuss it in every other bar. The levels of this fascination with knives depict not just a red-eyed habit, but a domestic lifestyle. “Blood on my shank, man keep it, clean it, use hot water and bleach it” raps 1011’s Digga D in “No Hook.” Loski and Mayski’s “Mummy’s Kitchen” talks of taking a blade from the family home, an act that boys in London are regularly excluded from school for committing. Remember: a large chunk of drill artists, and an even larger chunk of fans, are just teenagers.

Unsurprisingly, chicken-and-egg debates about the relationship between drill music and youth violence have garnered recent momentum on Twitter. It is no secret here that knife crime is skyrocketing: 39 young people across the UK were killed with a knife in 2017, the most in a single year since 2008. Four young men were stabbed to death in London on New Year’s Eve alone. This context, if not entrenched by the promotion and popularity of drill, is important for understanding the genre’s widespread appeal. Groups of teenage boys in the inner city are obsessed with its closed world. This obsession is fueled by speculation over social media about which driller has been sent to prison or what intelligence can be gathered from Snapchat about which “GM” (gang member) has been violated by who, adding to what is known as the “scoreboard” (how many people a particular group have collectively stabbed).

London rarely, if ever, experiences snow on Christmas Day. But on December 25, 2017, fans were waking up to discover the crisp, white, Icelandic plains of SL’s high-definition “Tropical” video. It had been released that morning by the Mixtape Madness channel, one of several urban music gatekeepers. The visual had reached over a million views by New Years Eve. SL, from Croydon, the grey suburban town where dubstep was founded, is only 16 years old. His year has begun in hyper-accelerated hood fame, having built upon the success of his prior hit “Gentleman,” which at the time of writing has amassed over 14 million views.

SL is a unique case. This is not only because of his laid back style of rapping compared to more high energy contemporaries. It is also because up until now, rather than standalone talents, crews have dominated the drill scene.

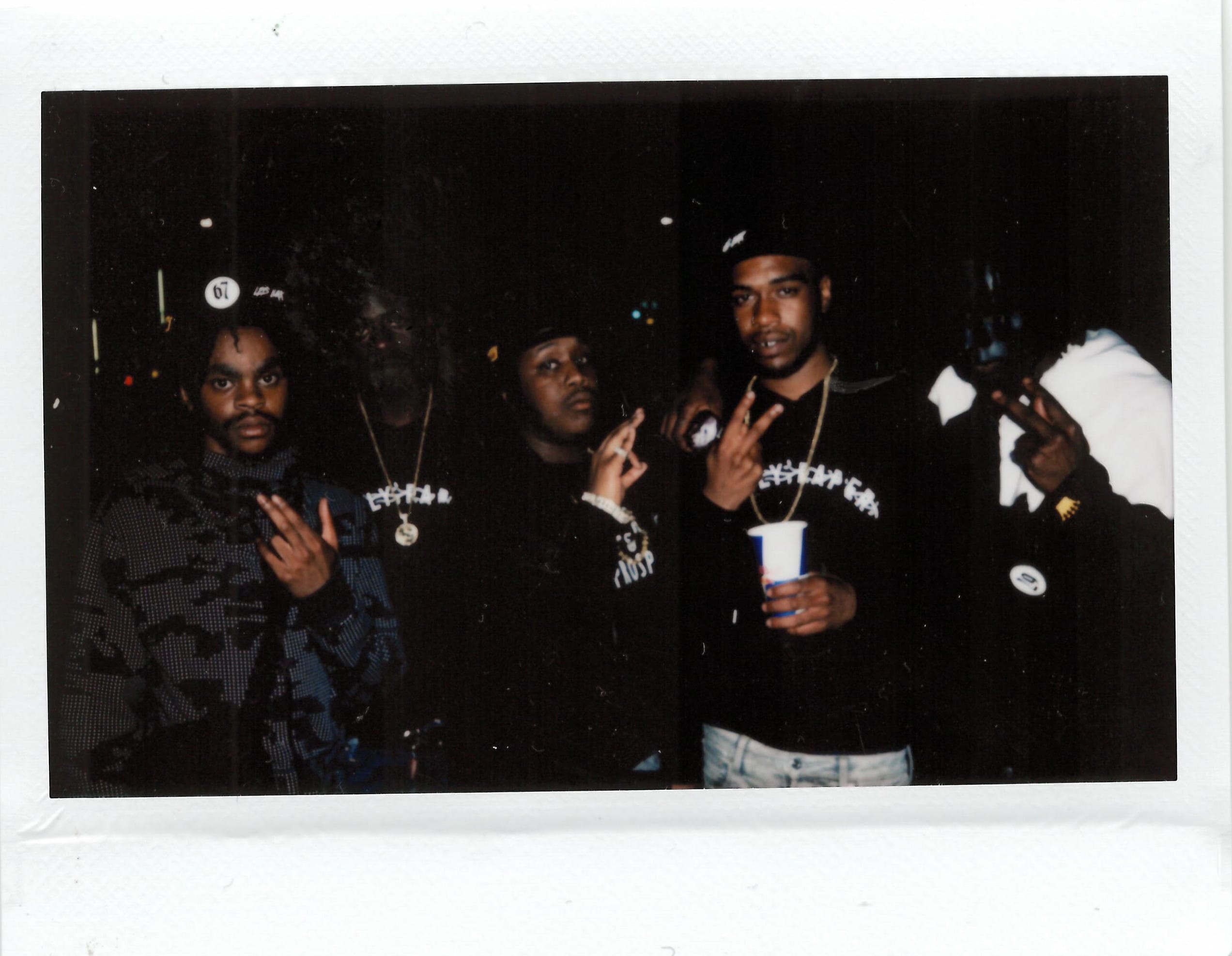

Since it all started, 67 from Brixton Hill, on the south side of the town, have been flag-bearers. After a whirlwind year, core members LD, Dimzy, Monkey, ASAP, and Liquez have multiple bodies of work and a selection of anthems like “Take It There,” “WAPS,” and “This Side” under their belts. You might recognize the instrumental of “Let’s Lurk,” the title track of their second mixtape, as the same used by Big Shaq in his globally viral parody freestyle “Man’s Not Hot.” The group’s unrivaled creativity has been steered by their prolific producer Carns Hill, whose new mixtape SRB Separation Confirmed came out last week.

On the northern side of Brixton live 67’s rivals, 150. One of the group’s youngest members M24 featured on recent banger “Do It & Crash” with Skengdo & AM. More than any other outfit in the scene, the latter pair’s rise shows why work rate is so important in drill: to be successful is to fill the algorithm-generated playlists of YouTube surfers by producing an abundance of fresh content. Skengdo & AM’s “Mad About Bars” freestyle (8.6 million views at time of writing) has more than twice the number of YouTube views than any other in the series. Their acclaimed recent mixtape 2Bunny was produced entirely by veteran duo D Proffit, and features eskibeat grime-influenced singles “Macaroni” and “Mansa Musa” (the latter is named after the fourteenth-century Malian king, regarded as the wealthiest person in history).

Skengdo & AM are members of group 410 alongside the likes of BT & Rendo and Syikes (whose “Bad Habits” channels Nas’ “Oochie Wally"). 410 are in a war of words with Harlem Spartans, who live only a few hundred meters to the north. It is worth highlighting that although not often featured on Harlem group tracks, their man of the moment is Loski. His tracks and distinct swagger—see “DJ Khaled,” “Teddy Bruckshot,” and “Money and Beef”—have brought a dancefloor-friendly current to the drill wave.

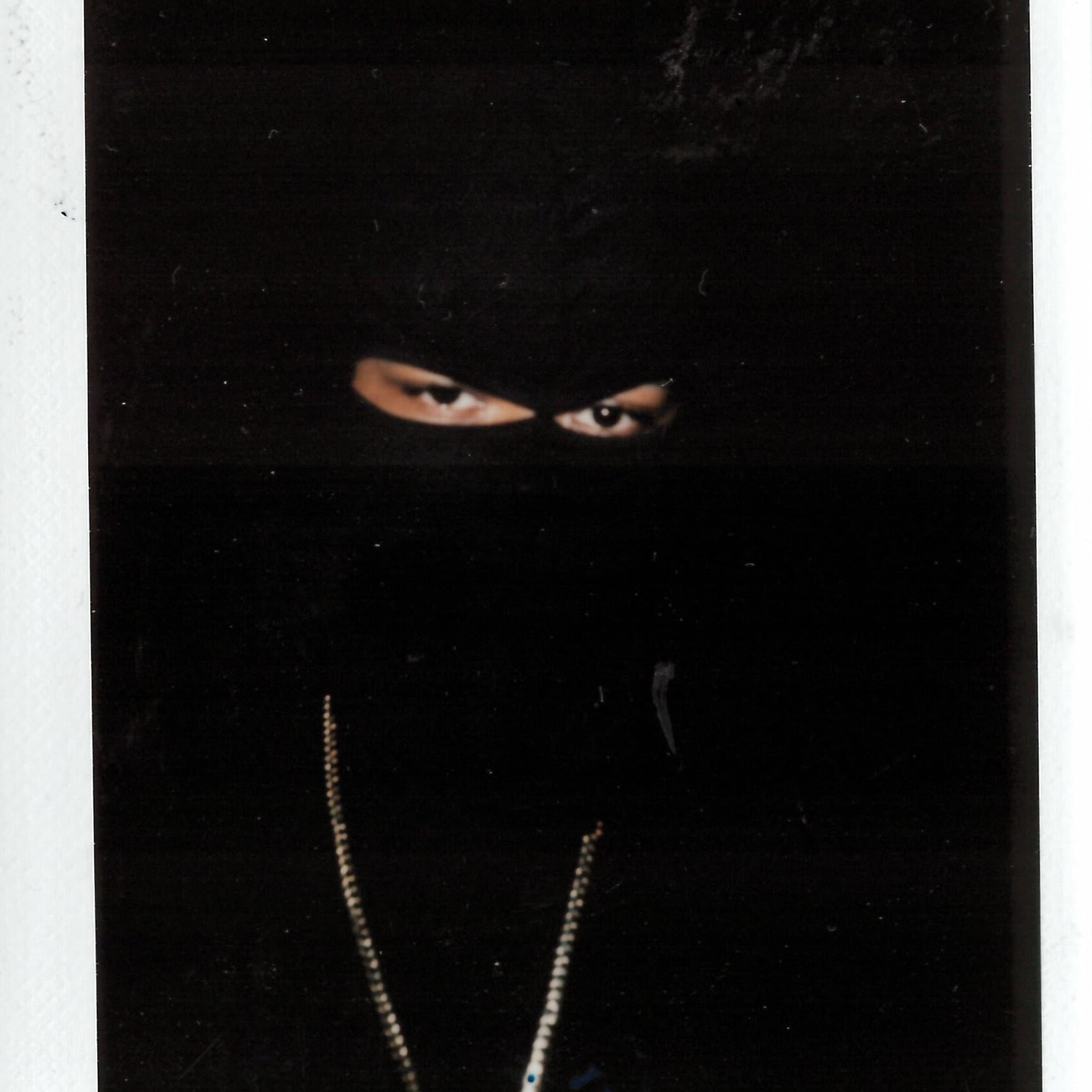

Permanently balaclava-clad K-Trap, another Brixton Hill native, was recently interviewed in Trench Magazine by London’s first young poet laureate Caleb Femi. He has a rare ability to commentate on the details of industrial-scale drug dealing with unparalleled conviction, and without it getting boring, a bit like Clipse did so effectively. His single “Watching” just came out, following the success of last year’s mixtape The Last Whip. Other prominent south London drill groups include teenagers Moscow17 from Walworth, who are at loggerheads with Zone 2, from Peckham (whose mixtape Known Zoo came out in December).

Of course, UK drill has set up camp beyond the confines of south London, demonstrating the genre’s ability to reinvent itself in disparate ends and spaces. Tottenham in North London—where grime king Skepta and the majority of the Boy Better Know collective are from—is home to Abra Cadabra, who won Best Song for “Robbery” at last year’s MOBO awards. The same is true of Headie One, who left prison last year and released his mixtape The One on Christmas Day, featuring popular track "Golden Boot."

1011 from Ladbroke Grove in West London—a stone’s throw from both the classy mansions of Notting Hill and the harrowing site of Grenfell Tower, which burned down last summer in a nationally-mourned tragedy that has become a lasting symbol of governmental neglect and urban inequality—have gained recent exposure from their riverside freestyle video “Next Up?” Their lyrics mocking a deceased rival called T-Wiz have been criticized as taking things too far—beyond the boundaries of drill’s moral compass.

Towards the end of “Nights in Harlem” by Max Valentine and Harlem Spartans, MizOrMac, whose words I quoted at the start of this article, speeds up his flow. You have to listen carefully to hear what he is saying:

“From caterpillars to butterflies, our drillers,

still out swimming,

out here fishing,

surviving the rivers,

you drown you ain’t with it.”

In 2018’s darkened slang lexicon, “swimming,” “drowning,” and “rivers” actually translate to someone swimming and drowning in rivers of their own blood, after being stabbed. To “fish” is to go out looking to stab opps, or enemies. What MizOrMac does in these horrific final lines is outline the nihilistic world that boys and young men like him are forced to inhabit. Caterpillars before they become butterflies, if they make it that far. And despite his grasp of semantic fields and metaphor, and the YouTube comments below his videos which say things like “MizOrMac got an A* at English GCSE!” or “Mizzy is way too talented!,” he has in fact been in prison since last summer. So many young people in London are becoming overwhelmed by their environments. In the words of local Elephant & Castle spoken-word rapper Jesse James Solomon, in his tranquil reflection “City Lights”: “boys that never got no food for thought, and got fed time.”

Drill is connecting with young people in this polarized city because it has become the voice of ignored adolescence. This is a mindset that has been left to fend for itself under the watch of a government that has maintained a stranglehold on British society over the last decade. Cuts to public spending—to mental health support, to youth-services, to education—have rendered the most vulnerable, unstable communities and their youngest members in increasing isolation. I do not believe for a second that the music itself is harmless—it isn’t. Like any form of language and art, it has the power to shift minds, especially those which are still developing and impressionable. But if anyone wants to blame someone or something for UK drill’s extreme content, and the sort of behaviors and lifestyles it promotes: blame inequality and the adults in society who could, but don’t, do anything to intervene.

The way I see it, from one angle UK drill is an expression of vicious rebellion; an attempt to find a new route out of the trappings of subsistent life. From another, if you delve beneath the bravado, stab-proof vests, and glossy veneer of gentrification, it’s a passionate cry for help.

Ciaran Thapar is a youth worker and writer based in south London.