1.

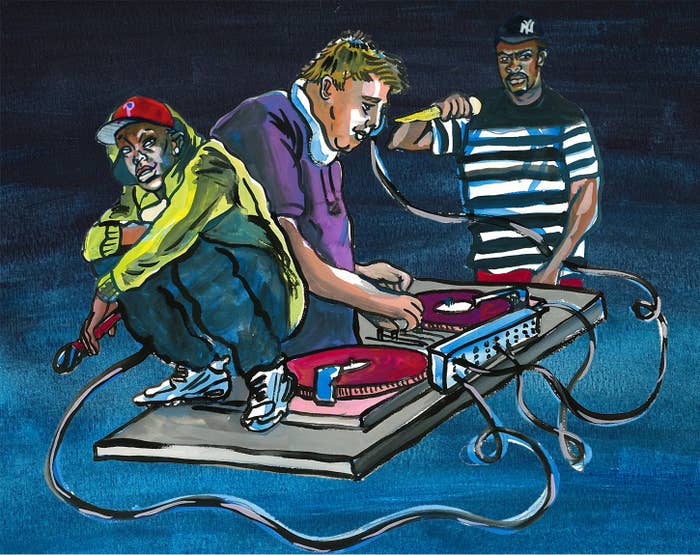

Image by Dana Paresa / L to R: Dizzee Rascal, DJ Slimzee, Wiley

Let’s face it, ever since Kanye decided to bring a bunch of grime artists on stage at the BRITs and Skepta and Drake became best friends, it seems the entire world is getting excited about grime. Something that comes up all to often is grime’s similarities to hip-hop; a Boiler Room article detailed grime and its relationship with America (using the term hip-hop no fewer than thirty two times), and those just getting familiar with the genre often refer to it as British rap.

These incessant comparisons frustrate and mislead, since—although there are shared characteristics between grime and hip-hop—grime is a musical form in its own right, with roots of its own. It needs to be made clear that a grime freestyle is different from a hip-hop freestyle, grime artists often end each line with the same phrase, and no, grime didn’t start last year with Meridian Dan’s “German Whip.”

Grime developed from a multitude of styles; primarily reggae, bashment, dancehall, garage, and drum and bass. To simply call it a subgenre of hip-hop disavows these vital influences, and denies the unique cultural heritage that has secured its place as one of the most vibrant and idiosyncratic performance forms that exists today.

Where it Started

Flashback to 2002 at Rinse FM—DJ Slimzee behind the decks, Wiley and Dizzee Rascal lyrically sparring in yet another unforgettable set at the time of grime’s formation. Their frenetic rhyming is unrelenting. They’re switching up patterns, taking over each other’s flow, and building the vibes on dub after dub after dub.

This music developed nearly 3,500 miles away from Brooklyn, in an area called Bow, in East London. A darker, more visceral sound than erstwhile flavor of the month UK garage, the lyrical content and the sound of the instrumentals more aptly represented the lifestyle that these artists lived. Whilst garage MCs were sipping champagne and amassing No. 1 Singles, Dizzee and Wiley were documenting the hardships they encountered. As DJ Target of Roll Deep said on his 1Xtra Stories documentary, “It’s a 140 bpm type of life,” meaning fast-paced, agitated, and always moving.

Slimzee’s sessions and the Roll Deep takeovers soon became established as essential listening for anyone interested in this new sound. Of course, you had to be fortunate enough to live within Rinse’s catchment area. Anyone who wasn’t had to rely on bootleg tape-packs, the equivalent of musical gold dust. Over time, the styles—known as “eski,” “sublow,” or “8-bar”—emanating from London’s vibrant pirate radio stations were placed under the umbrella term “grime.” The rest is history. Dizzee Rascal won a Mercury for Boy in Da Corner in 2003, Lethal Bizzle’s “Forward Riddim” (better known as “Pow”) single-handedly tore up every rave inside the capital, and Wiley’s creative endeavors bought him a big old house in the country.

Artists were making grime way before Drake and Kanye cottoned on to it. In 2002, Kanye was still very much in his musical infancy, showing great promise as a soul-sampling beatmaker. Drake was still on Degrassi. During the origin of grime, hip-hop wasn’t a part of the discussion.

6.

Image by Dana Paresa / L to R: DJ Spooky, King Tubby, Footsie

The Dubplate Special

Grime’s clearest forefathers are reggae and dancehall, not hip-hop. Logan Sama mentioned this in a recent discussion, as did Novelist in July’s No Ceilings interview. It’s even broken down by Breakage and Newham Generals with the tune “Hard,” in which David Rodigan symbolically passes the torch in his speech halfway through the track. Tracing the lineage of reggae and dancehall culture directly to grime is easy when we consider the almighty dub—the rework or remix of an existing recording.

This continuum stretches back to King Tubby and Lee “Scratch” Perry tinkering away in Studio One, Kingston, Jamaica. The mentality of re-visioning—or what reggae theorist and filmmaker Julian Henriques calls “re-presenting”—existing music in new forms is at the crux of Jamaican music culture. The mass migration from the West Indies to the UK in the 1950s saw the culture come with the people, and acts such as Steel Pulse and Channel One Sound System are as British now as a cup of Earl Grey and a digestive biscuit, while their culture of dubs has been readily incorporated firstly into drum and bass and then grime.

For grime DJs, having their own mix of a popular track, a version with their producer tag, or a tune that no one else has is the best way to guarantee a must-listen set. Slimzee is a master of dubs, DJ Spooky practically refixes a tune a day, Big Mikee has dubs from an unsurpassed list of Birmingham MCs, and Logan Sama’s name-drops are legendary. The dub has a special place within grime.

Take “Pulse X” by Musical Mob, for example. This certified classic was refixed by Musical Mob themselves to make “Pulse Y,” and subsequently chopped up by the outrageously prolific Spooky for “Pulse 007,” (complete with sound effects from PlayStation 2 badboy Nightfire). Earlier this year Mystry dropped yet another version in the form of “Pulse 8” on Stripes Records.

“This isn’t a proper freestyle, bruh!”

Endless comments on YouTube videos and blog articles about grime point out the difference between a grime freestyle and a traditional rap freestyle. In grime, much of the material is pre-written and the bars have often been heard before. The freestyle in grime—such as Skepta’s notorious nine-minute epic for Westwood—is a live marrying of existing lyrics and instrumentals, but presented in a completely new way. This was formalized on Logan Sama’s KISS show with his Versus Sessions where MCs took on an instrumental each week.

It’s a well-established method, and yet videos are still inundated with angry comments calling out grime freestyles for not being “real” freestyles. It’s a separate methodology, and persistent comparisons to hip-hop just lead to unnecessary confusion. What most grime MCs are doing is riding the beat and working out which lyrics will work best with each instrumental as the DJ continues to drop in new beats. The artists are thinking on their feet, and keep in mind: the beats are nearly twice the tempo of most hip-hop tracks.

Toasting and MCing

A grime freestyle shares more common ground with the practice of a DJ toasting at a Jamaican sound system session or a drum and bass MC controlling a rave. Wiley earned his stripes MCing over d’n’b as far back as 1998. This session with DJ Target on the 1s and 2s was just one of a plethora of sets in which the early grime MCs learned their craft. D Double E, Riko Dan, and Dizzee Rascal all began in this fashion, paving the way for their trademark performance styles. And you can hear this training in their freestyles today: quick, punchy, and memorable.

What is most needed as a grime MC is the ability to curate a session—or performance—and the unbridled energy to keep the ravers on their feet (or the listeners locked if they’re tuned into the FM). Capturing a crowd with a lyric and keeping them engaged for the duration of a session, which can last for hours at a time, is a special skill. This requires an understanding of the crowd, an appreciation of pacing, and the ability to repackage and reconfigure existing lyrics to match the mood of the surroundings.

This unique tradition and set of skills has been passed down through the generations. It’s only natural; grime MC and producer Footsie’s dad, Father Waz, was part of the King Original Sound System, and Jammer’s dad used to run a sound system, too. Without his approval the legendary clashes in the basement for Lord of the Mics may never have happened, and, according to Wiley, Eskimo Dance wouldn’t have existed either.

11.

Image by Dana Paresa /L to R: Novelist, Jammz, Mez

I’m not trying to argue that grime is not at all influenced by hip-hop. But to call grime a subgenre of hip-hop is to reduce it to an offshoot of an art form that has itself been the subject of reductive conceptions, and to do so inaccurately. Grime’s history is complex and multi-faceted, and although it may sound and look like some English version of American rap, it’s way deeper than that. To categorize is to subsume, and in a time where grime is finally getting the wider recognition it deserves, we’d do well to stop saying that grime’s a subgenre of hip-hop and start venerating the music on its own terms.