By Chinwe Oniah

We need to talk about black women in music. The recent rise of female artists—starting with Lil’ Kim and TLC and continuing today with Nicki Minaj and Beyoncé—have been defined by black women who have made it their mission to be open about sex. Reclaiming their bodies has not only been an act of self-love, but of defiance.

But in taking back their sexuality, black women in a sex-driven industry have experienced some whiplash. With its reliance on objectification, the music industry has stripped away the opportunity for depoliticized displays of sex. And it doesn’t swing both ways—Miley Cyrus can twerk on Robin Thicke and the talk is all about how she’s pushing boundaries. A black woman in that same performance would not have been hosting the same show the following year.

Reclaiming their bodies has not only been an act of self-love, but of defiance.

Throughout the years, the black female body has been maintained as a complex and highly politicized form. For black women, race is often sexualized and sexuality is often racialized. Existing in this paradigm makes it hard for black female artists’ art to exist solely as art—it always comes with that extra layer.

Some women have taken this element and used it to their advantage. Nicki Minaj, for example, has made it her business to use explicit sexuality in her music. Even through the wacky outfits and rainbow hair phase, sex has always been at the forefront of her music. The most iconic piece of work she has produced to date is “Anaconda,” a raunchy song focusing primarily on the large back end of a woman.

Sex sells. This we know. This Minaj knows. What she’s done differently with “Anaconda” is glorify strong, thick bodies for being awesome in their own right. Sure, there will be people that ogle her and solely see her as a sex object. But people are looking at her because she made them look. And by making them look, she’s able to say, “I’ve gotten you here with my body because I wanted to, and I did.”

She’s given herself autonomy that puritanical critics have tried to take away. Regardless of whether the implication that she’s too sexy because she’s black, or because she’s black, she’s too sexy, that’ll always be the thing to reel them in. And once she’s reeled them in, she can communicate whatever message she wants. They are now on her playing field.

While Minaj makes the best of her dilemma by exploiting the lustful gaze, other black female music artists have rejected that kind of explicit acknowledgement. They acknowledge that they are people, and as such are sexual beings, but this is not the focus of the music. But when that musical focus comes into conflict with a sudden expression of sexuality, people get confused. Can a woman not be sexualized in her music and still be sexual?

When Janelle Monáe came on to the scene, she was lauded for her sartorial choices, which included immaculately tailored suits, sleek hairdos, a flawless face, and a positive, PG message.

Rather than take the shortcut of luring people into her work through sex, Monáe chose a different kind of creativity. She created a separate world for herself, where she and her fans are androids (and as such, not prone to human urges). She has a robotic alter ego, Cindi Mayweather. Visuals allude to Fritz Lange’s robotic Metropolis. When her career began, she was almost always in a suit. Sonically, she hops all over the place, from doo-wop and hip-hop to classical music. Janelle Monáe given viewers and listeners and experience so fully about the music that sex is an afterthought, if it’s there at all.

But as Monáe’s career took off, focus shifted from her music to her body. Questions like, “Why does she wear the same thing all the time?” and “What does her body look like?” and, “Is she straight? Gay? Bi?” threaten to commandeer the path of her career and dominate the discussion of her music.

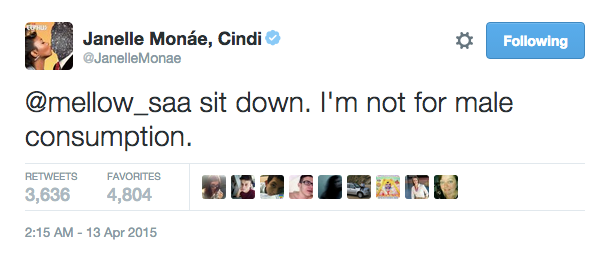

Monáe has fought back against critics, saying that her suits act as a uniform for her music. She recently slammed an internet sexist after he tweeted at her to “stop being so soulful and be sexy… tired of those dumbass suits”:

2.

But lately, Monáe has been leaving her formal look behind. The black and white color scheme still stands, but she’s started wearing t-shirts, moto jackets and a crop top. Her clothing choices now show off her figure. Even in her single “Yoga,” she shows off body rolls with her midriff showing, singing about being her own private dancer. One of the song’s most quoted line reads, “You cannot police me so get off my areola.”

Monáe is an artist that almost anyone can identify with. She’s weird but relatable. She’s small, but confident. She’s sexy, but conscious. She’s a complex person whose work doesn’t confine her to one box. She’s versatile. But she’s received backlash for “Yoga”; she’s being sexy and therefore, she’s selling out.

Monáe’s struggle represents the dilemma for black female music artists. If you’re black and female in the music business, you’ll be sexualized. Not just because sex sells, but because it’s expected of these artists. Minaj was able to profit from it. Monáe tried to do it on her own terms and people didn’t get it, or worse: they wouldn’t accept a black female artist that didn’t lead with sex appeal.

The intersectionality of being black and a woman is oft times lost on people. Where our white contemporaries worry about equality of the sexes, black woman are worried about being equal as women and not being sidelined for being black. Skinny white models parading in almost nothing can be plastered all over magazines, but Minaj’s exposed body is NSFW. Iggy Azalea and Jennifer Lopez can have a song and video about ass and no one bats an eye. Miley Cyrus even photoshopped her face onto Minaj’s body, then turned around and dismissed her argument about black women and the VMAs.

Minaj and Monáe seem trapped by their cultural stereotypes. They’re damned if they do and damned if they don’t. Minaj tries to exploit sexuality. Monáe tries to be casual about sexuality. They are, in their own way, trying to cope with the cards they’ve been dealt by spotlighting and deflecting their sexuality, respectively.

But FKA Twigs wields it.

Compared to that of her contemporaries, Twigs’ sexuality is almost sinister. The same vulnerability that some men take advantage of is the same vulnerability that Twigs uses to exert her power. This permeates through every part of her performance and the music she produces. The juxtaposition of her soft voice against the backdrop of heavy industrial and dark production, weighted by her lyricism and enforced by her visuals is enough to make the most ardent misogynist to tremble.

“I’m Your Doll,” a track from her third EP, M3LLI55X, is the most menacing. The lyrics—”I’m your doll / Wind me up / I’m your doll / Dress me up / I’m your doll / Love me rough / I’m your doll”—allude to a sarcastic willingness to be submissive, but not because she is submissive. The video drives the point home: We see a man in horrific close-up, slobbering over Twigs’ blow-up body after she’s baited him into bed with her. As disturbing as the image is, Twigs is able to reassure the viewer that she’s in control. The “submissive” is the dominate one.

This sort of avant-garde sexuality exists in the surreal, in a space not as clearly delineated by race. This approach repositions sexuality as a malleable, rather than fixed, point of entry with regards to music: Twigs can be repulsive, unsettling, and sexy in equal measure. But she can’t be held as just a sexual object, because the average viewer can’t get past the surreal.

Twigs can be repulsive, unsettling, and sexy in equal measure.

Pregnancy, which can be fantastical and almost unreal for a third party—especially for male viewers—is held in especially high regard by Twigs. She has waxed poetic about the sexiness and power a woman has when she’s pregnant, saying, “I would argue anyone into the ground who says a woman’s not beautiful or sexy when she’s pregnant.”

Still, there are seemingly only a few boxes black women can inhabit, and they’re all oversimplified tropes. Minaj, Monáe, and Twigs have all found ways to either make the best of the constrictions, or attempt to break out. And it doesn’t matter which approach they take. Azaelia Banks, Tink, Syd the Kid, Jasmine Sullivan and others have immense talent. They all deserve the chance to make those decisions for themselves and not feel stymied by industry expectations.

In an industry where sex and scandal are currency, the packaging is more important than the quality of the content. These black women have to figure out how to package and sell themselves—sadly, it’s still standard issue to be a sex object first and an artist later.