1.

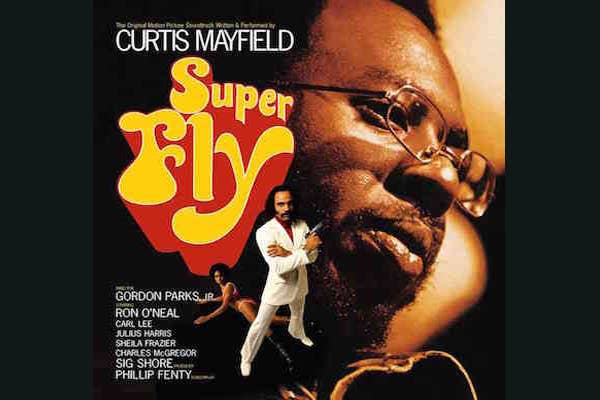

2. Curtis Mayfield – Super Fly

Year: 1972

When Eminem put together the track “I’m Shady” on his 1999 album The Slim Shady LP, he was surprised to learn he was referencing Curtis Mayfield, not Ice-T, on the chorus. Eminem was only familiar with Ice-T’s 1988 hit “I’m Your Pusher,” which sampled soul, R&B and funk legend Curtis Mayfield’s 1972 track “Pusherman.”

Eminem’s ignorance here, though understandable (by his own admission he grew up strictly into rap music), indicates that we need to be reintroduced to Mayfield. All of his work of the early-to-mid-’70s is recommended, but Super Fly, a soundtrack to the 1972 film of the same name, is the perfect entry point.

First of all, the aforementioned “Pusherman” is addictive. Over a perfectly layered bed of bass, drums, percussion, guitar and wah-wah, Mayfield writes from the point-of-view of a drug dealer with an eye for detail and engaging playfulness. Elsewhere, we’ve got classics like the orchestral funk of “Little Child Runnin Wild” and the dirty groove “Freddie’s Dead.” Even the two instrumental songs fit the album’s mood well.

There were a lot of other great Blaxploitation soundtracks, but this is one that transcends the movie associated with it—the soundtrack out-sold the film.

3. Eightball & MJG – Comin’ Out Hard

Year: 1993

Among landmark southern rap albums—examples include UGK’s Ridin’ Dirty, Goodie Mob’s Soul Food, OutKast’s Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, Odd Squad’s Fadanuf Fa Erybody!!, Geto Boys’ We Can’t Be Stopped, Three 6 Mafia’s Mystic Stylez, Paul Wall and Chamillionaire’s Get Ya Mind Correct, T.I.’s King and Young Jeezy’s Let’s Get It: Thug Motivation 101, which, unbelievably, just hit 10 years old—this one flies under the radar.

Slipped out in August 1993 on the unknown Suave House Records, the album put Memphis, Tennessee, on the rap map and has gained in stature over the years. The liner notes are sparse, “Special Thanks To: God, all of our parents, and everybody who worked hard to make this shit jump off. Smoke One!” Moving on to the equally scant production credits reveals that Eighball and MJG produced, engineered and mixed the album.

That’s impressive given what’s here. Nine tracks begin with MJG threateningly introducing the duo with a demented effect on his voice before cackling like a demon while audibly smoking pot. From there it’s non-stop bouncy funk; a mixture of live instrumentation and weaponized samples over appealingly hollow programmed drums with non-stop rapping throughout; these guys weren’t too into choruses.

As for lyrical content, there’s a lot of straight bragging here, and they sound great doing it, but there are moments that reach beyond that. Over a sample of the 1983 quiet storm “T.K.O.” by Womack & Womack, “Pimps” flatly outlines the subject of pimping; lyrically unforgiveable but infectious nonetheless. “Armed Robbery” let’s us ride along with Eightball and MJG on two crime sprees they’re committing concurrently, describing themselves robbing banks, shooting and stabbing people step by step over a deft recreation of Lalo Schifrin’s Mission: Impossible theme.

Why did they do all this? Eightball says, “I took the money for the sake of me livin’ poor and wishin’ to be richer, and just like Picasso, I had to paint a picture.”

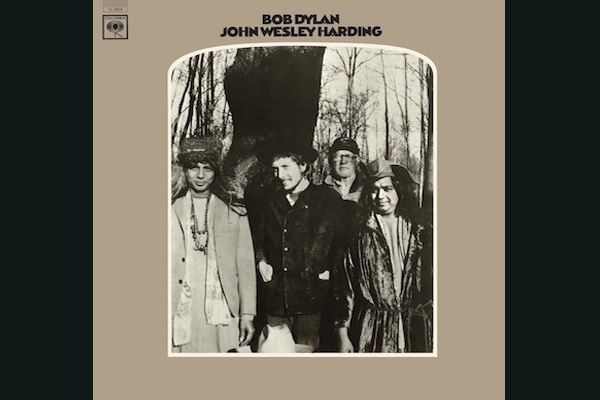

4. Bob Dylan – John Wesley Harding

Year: 1967

John Wesley Harding came at a time when Bob Dylan had just been on an incredible seven album run that saw him go from a funny little folky imitating Woody Guthrie to a media sensation, unfairly labeled the voice of a generation and forced on whirlwind tours backed by a band (The Band), for which he drew boos. His last album, Blonde on Blonde, had exploded what he called “that thin, wild mercury sound” across four sides of vinyl, so it was obviously time to tone things down a bit.

As he recounts in his 2004 autobiography Chronicles: Volume One, around this time, Band guitarist Robbie Robertson asked Dylan, “Where do you think you’re going to take it?” Dylan asked, “Take what?” Robertson answered, “You know, the whole music scene.” Dylan was taken aback; he was obviously under a lot of pressure. The other problem was that in 1967, “the whole music” scene had already found its direction; psychedelia, a sound Dylan had nothing to do with.

He wisely went in the exact opposite direction, decamping from upstate New York for Nashville, recording with the simple accompaniment of three ace country session musicians. The resulting dozen songs are amazing, ranging from the crisp country funk of the titular outlaw tribute to the terrifying “All Along the Watchtower,” the later a huge hit for the Jimi Hendrix Experience. A highlight is “The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest,” which irresistibly lopes along as Dylan tells a tale of these two characters that seems to mean everything and nothing at all (it was intended as a parody of what were then called “message songs”). All in all, the album is the quiet morning-after of the wild hash he’d made of the ‘60s. It’s Biblical, ebullient, ruminative, concise—everything really.

5. KMD – Black Bastards

Year: 2001

Few shelved hip-hop albums get a happy ending like this one. Comparatively cuddly (their debut single was called “Peachfuzz”) underground NYC rap group KMD was basically done preparing its more militant sophomore album Black Bastards when lead MC Zev Love X’s brother Subroc was killed trying to cross an expressway. This, combined with the album’s racially charged cover art, caused Elektra to shelve the record and drop the group. Fondle ‘Em Records put it out five years later and it’s been reissued a couple times since—it even came out as a lame pop-up book this past Record Store Day.

Listening to it, it’s easy to see why it endured. It’s a perfect rap record; every track is irresistibly funky and elastic, and Zev Love X (soon to reinvent himself as MF DOOM) is on point. Sample lyric: “I got it, my tool, my utensil to draw lead in that ass like a pencil with a stencil. And let me see them kids who had beef in the summer, and they mugs, all look like Helen Keller but dumber; ain’t that a bummer? I’ll take you out your misery; I’ll be the mad bluff caller like, caller ID motherfucker!” This has it all; black power, sex, weed, humor, dense posse cuts, the works. Check the lengths to which Zev Love X will spin the simple story of a bus driver refusing to drive his group to its next tour stop unless they stop smoking pot and bringing on girls (“plus he said no bitches on the bus except for his one bitch”) on “Contact Blitt.” We take it for granted now, but thank God this album finally made its way into wide distribution. Makes you wonder how many other lost classics lurk on Ampex reels or in dusty corners of someone’s hard drive.

6. Black Flag – Damaged

Year: 1981

Way before he was doing car commercials and amassing a curiously long IMDB entry, Henry Rollins somehow managed to sneak his way from working at a Häagen-Dazs into fronting the already existent Black Flag; probably the best California punk band of the ‘80s. Damaged, the band’s debut album, faced immediate controversy; MCA didn’t want to release it as its executives found it “anti-parent.”

When it was finally released in 1981, it spawned the closest its genre can come to hits; “Rise Above,” “Six Pack,” “Gimmie Gimmie Gimmie”—these immediately felt like anthems. “TV Story” appeared in the must-see cult movie Repo Man three years later. “Police Story” delivered a message of frustrated outrage at police harassment that certainly still resonates today. And that’s all just on the A-side.

The B-side digs deeper and more inward, with slower, dirge-like songs “Life Of Pain” and “Damaged I” providing a preview of how far afield of punk standards Flag would be willing to go on later albums.

7. Lou Reed – Berlin

Year: 1973

Getting into the Velvet Underground is fairly simple; four albums and you’re done. For around $40 on Amazon, anyone can get the 1995 box set Peel Slowly And See and have the full discography plus enough ancillary material to keep all but the most ravenous music dork happy.

Walking into Lou Reed’s discography is a whole different animal. He put out 22 solo albums in his lifetime. Were he still alive, he’d have us believe each and every one of them is brilliant. They’re not; they’re a real crap shoot. For every Street Hassle, there’s a Mistrial. Even there, though, there’s a logical point of entry; Transformer, with the A Tribe Called Quest-sampled, Nelson Algren-invoking “Walk On The Wild Side” and the Trainspotting-scoring “Perfect Day.” But Reed scored one of his biggest solo career victories a year later with the 1973 album Berlin.

According to Reed, the idea was simple. Write an album stocked with characters song to song, then have them interact with each other. What this added up to was the tale of a couple named Jim and Caroline wrapped up in addiction, sex work, depression, abuse, and death. But, to hear Lou tell it, this was “very nice; it was paradise.” Looking back on his legacy, Reed seemed to realize he was onto something here; in 2008, five years before his death, he resurrected Berlin for a recorded and filmed live performance.

8. DJ Shadow – The Private Press

Year: 2002

DJ Shadow’s 1996 album Endtroducing..... is a landmark; it already has a two-disc Deluxe Edition reissue and holds the Guinness World Record as the first album to be recorded using only sampled sounds. If anyone’s going to get one DJ Shadow album, it’s going to be that. But his follow up, The Private Press, is maybe better (gasp). It’s more open than Endtroducing and seems to labor less under the stress of Shadow’s disciplined production method. Regardless, it’s worth picking up on because he’d never grace us with an album like this again.

Over 14 tracks—charmingly bookended by a privately pressed audio letter from a woman to her distant relative—Shadow gives us everything we could want out of an album by any sort of artist, sample-based hip-hop or otherwise. The disc has moody atmospherics over killer drums (“Fixed Income,” “Giving Up The Ghost,” “Mongrel…Meets His Maker”) dense hip-hop instrumentals (“Walkie Talkie,” “Right Thing/GDMFSOB”) psychedelia (“Six Days,”) rock (“You Can’t Go Home Again”) and even a big ‘80s prog-pop moment (“Blood on the Motorway”).

Every song builds steadily, adding textures upon textures and coming to its own embryonically conceived of conclusion rather than having to return to the same signature sample that started the song to finish it.

9. Funkadelic – Maggot Brain

Year: 1971

Getting into George Clinton’s bands Parliament and Funkadelic is a daunting task. To start with, the two main bands released around 20 studio albums, and then there’s the constellational orbit of solo efforts, side projects and live albums that surround them. For Generation X, hip-hop provided many in-roads to both bands.

For example, “Me, Myself and I” by De La Soul likely sent a crate digger straight to “(Not Just) Knee Deep” off Funkadelic’s 1979 album Uncle Jam Wants You. “Let Me Ride” by Dr. Dre points straight to the 1976 Parliament song “Mothership Connection (Star Child)” off the album Mothership Connection. We could do this all day—these two bands are among the most sampled on Earth—but a Funkadelic sample hit the airwaves more recently courtesy of a less likely artist. In 2010, Sleigh Bells, more known for pounding guitar and drum machines than rollicking acoustic rock, scored a hit with “Rill, Rill,” sampling Funkadelic’s 1971 song “Can You Get to That.”

This was on Maggot Brain, the band’s third album, which captures Funkadelic transitioning from a ball-busting psychedelic rock band to one more in keeping with the name. It begins with a blistering 10 minute guitar solo that guitarist Eddie Hazel arrived at by Clinton telling him to “play like you just found out your mother died.”

Elsewhere, tracks like “Hit It and Quit It” and the awesomely titled “Super Stupid” flatten the listener with Hendrix-esque funk rock; a concoction they’re basically inventing right in front of you. “You and Your Folks, Me and My Folks” and “Back in Our Minds” throw in some class- and social-consciousness without losing any of the band’s inherent playfulness. Finally, George being George, he closes out the proceedings with the 10-minute freak-out “Wars of Armageddon.” All in all this might be the best singular project in the Parliament/Funkadelic cannon.

10. George Harrison – All Things Must Pass

Year: 1970

If you want to get into The Beatles, get into The Beatles. Start with Please Please Me and don’t stop until you’ve gotten to Abbey Road. After that, if your head hasn’t exploded, you’ve got nearly 70 solo albums from John, Paul, George, and Ringo to choose from, so go listen to all of them!

Just kidding; that is a very patchy field to walk into. The four were never as good alone as they were together; particularly Lennon and McCartney. For that reason, the best Beatles solo album of all is likely George Harrison’s 1970 album All Things Must Pass; his first proper release (he’d put out two experimental albums previously). For the Beatles’ entire run, Harrison had been allowed to contribute one, maybe two songs per album. Harrison later told Rolling Stone, “It was like having diarrhea and not being allowed to go to the toilet.” This isn’t the most appealing way to describe one’s music but it came out here; 23 tracks spread over three discs that came in a box set. It’s difficult to know where to start unpacking all this; two-dozen musicians back him and this includes names like Billy Preston, Eric Clapton, Ginger Baker, and even Ringo Starr, along with some of the most famous session musicians around. Oh, and it was produced by Phil Spector.

The main event is the 18 songs on the first two discs. Throughout, Harrison sounds resolute and invigorated. Love and lust are frequent topics, when he’s not searching for the meaning of life itself. It all starts with a song co-written with Bob Dylan, “I’d Have You Anytime” – elsewhere Harrison does a great cover of Dylan’s recent composition “If Not For You” The rest really runs the gamut. “Wah-Wah” is a stinging jab at John, Paul, and Yoko Ono, while he’d demoed the title track for the Beatles. The hit “My Sweet Lord” is the first big indication of the spirituality that would come to permeate, then dominate his later work. “Let It Down” alternates between gorgeously balladry and the type of a big chorus possible when you have both Badfinger and Derek and the Dominos backing you on a song. “Apple Scruffs” is a blast of acoustic guitar, harmonica and pop harmonization that wouldn’t have sounded out of place on the White Album. “Art of Dying” should have been a Bond theme.

It all ends with four self-indulgent jams spread over the third disc that somewhat detracts from the album, but it didn’t matter. Harrison had made his point. Just as the Beatles were collapsing, he released a wealth of proof that he was as good a songwriter as the other two.

11. Kool G. Rap & DJ Polo – Road To The Riches

Year: 1989

Before there was the Notorious B.I.G., Nas or Jay Z, there was the original king of New York, Kool G. Rap, the illest member of the Juice Crew. Dude rapped with a lisp and was lyrically hard enough no one really noticed. On this, his 1989 debut album, G. Rap has all angles covered. He wasn’t going to get rich or die trying (or declare bankruptcy); he’s audibly confident he’s on his way (see the title track).

“It’s A Demo” rides the “Funky Drummer” sample as hard as it can be rode, while “Men At Work” stomps all over the Incredible Bongo Band—basically every essential hip-hop sample is going to get aired out and spat all over. But G. Rap laid down some sampled material himself; his exclamation of “Poison” was rewired to explosive effect on Bell Biv DeVoe’s debut album Poison and accompanying hit single “Poison” the following year (an accident at the time—these days such a thing would have been mapped out and cross-promoted months in advance).

The best, perhaps, is “Truly Yours,” on which, over a blend of samples of Timmy Thomas and Kool and the Gang, G. Rap tells off various types beneath his contempt. It’s endlessly quotable, but perhaps best is that he declares that, because his label is distributed by Warner Bros., he’s “gettin’ Bugs Bunny money.” So, like, carrots and dynamite?

12. David Bowie – Low

Year: 1977

His 1977 album Low was conceived of and released at a strange time for David Bowie. Over the last 10 years he’d released many albums, twisting himself from a whimsical English pop singer to a rock star from outer space named “Ziggy Stardust” and even briefly dallied with American R&B before reimagining himself as “The Thin White Duke.”

For his next move, all that was out the window and Bowie relocated to Berlin and France to record Low in collaboration with Brian Eno with participation by Iggy Pop. The resulting album—it’s A-side stuffed with taut, sharp, sleekly modern short songs and its B-side four slow instrumental soundscapes—was brilliant and undeniably one of Bowie’s best. Upon release, it tanked. Bowie was pleased.

It was, as the cliché goes, ahead of its time. The first song, “Speed of Life,” though irresistible, had no words and a squalling synth throughout. Where there were words here, they could be disturbing, like, “Baby, I’ve been breaking glass in your room again, listen, don’t look at the carpet, I drew something awful on it.” One of Bowie’s best, biggest songs, “Sound and Vision,” is right here but annoyed listeners may have simply missed it, particularly since it takes a full minute and 27 seconds to get to Bowie’s first line.

The slow, creeping “Always Crashing in the Same Car” is a masterwork of perfectly placed, futuristic instrumentation that artfully uses reckless driving as a metaphor for making the same mistakes over and over again. Meanwhile, the beautiful, mid-tempo instrumental “A New Career In A New Town” manages, with no words, to portray the rush of optimism that comes with a fresh start.

The instrumental B-side must have seen baffling at the time, sure. It’s one of those things you’ve got to find the right time, place and mood to listen to. It’s best taken back-to-back with the B-side of Bowie’s next album “Heroes,” which also featured instrumentals in a similar vein, and maybe with some of Eno’s Ambient albums on hand as well. If you like Low, it’s the first album in what’s called Bowie’s “Berlin trilogy,” the next two albums being “Heroes” and Lodger. Some people get so immersed in this period of Bowie’s discography that they find no need for anything else he ever did.

13. Led Zeppelin – Physical Graffiti

Year: 1975

Speaking to NPR when it was reissued this year almost 40 years to the day after its original release, Led Zeppelin guitarist and principal Jimmy Page called it “the mother of all double albums.” This is, perhaps, a bit immodest, but at least close to true. Its competition would be a short list; Exile On Main St., Blonde on Blonde, The White Album, Quadrophenia...

It’s also the Led Zeppelin album casual fans might not get to—or through. I, II, III, IV, and Houses Of The Holy are no-brainers. Physical Graffiti is where the band stretched its legs and started challenging listeners more. Part of its range stems from how it departed from a set time period in its development. Only eight out of 15 songs on it were recorded for its release. The other seven ranged as far back as the recording sessions for Led Zeppelin III. It was the band saying, “This is who we are now, mixed with who we’ve been”—though fans at the time may not have been clued into this. Regardless, it was them presenting everything they were about to the record-buying public.

No surprise, then, that this album has immense range. Among the new songs, you’ve got down-and-dirty rock on the album’s openers and closers, “Custard Pie” and “Sick Again”; funk in “Trampled Under Foot”; prog weirdness in “In The Light”; truly astounding slide-guitar pyrotechnics in “In My Time Of Dying”; experimentation with Middle Eastern textures in “Kashmir”; proto-metal in “The Wanton Song”; and a sweeping ballad in “Ten Years Gone.” The Houses Of The Holy outtakes “The Rover,” “Houses Of The Holy” and “Black Country Woman” slot perfectly among all this—and who else would put out an album called Houses Of The Holy and then slip a song called “Houses Of The Holy” on their next album? Among the Led Zeppelin IV outtakes, “Down By The Seaside” defies categorization, with a breezy verse and chorus befitting its title but with a rock bridge that shouldn’t fit the song at all but somehow works perfectly. “Night Flight,” meanwhile, is a baffling slice of country rock that recalls The Band, while “Boogie With Stu” features the Rolling Stones’ Ian Stewart, always welcome. Finally, the shimmering acoustic instrumental “Bron-Yr-Aur” takes us back in time five years to the writing sessions for Led Zeppelin III; a perfect excursion.

The funny thing is that, as brilliant as this mixing of eras of the band was, the band had shot itself in the foot. They mined a vein similar to their contemporary material here on their next album, Presence. Without the older material breaking up such intensity, fans reacted adversely.

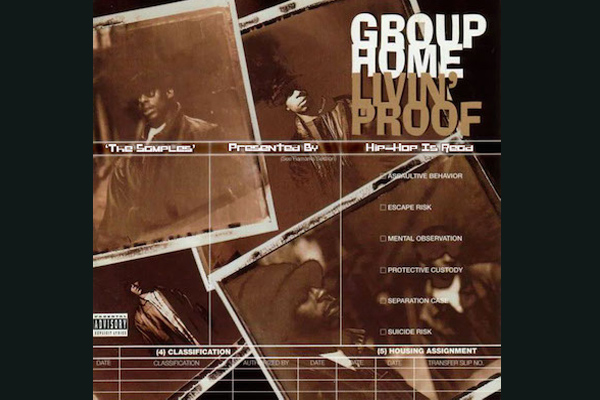

14. Group Home – Livin’ Proof

Year: 1995

In 1995, if you were a New York City rap group selling gritty, street-level observations over raw, sample-driven beats, it was like, “Join the club.” Post-Wu-Tang Clan, everyone was doing that. It didn’t help Group Home’s case that their star producer, DJ Premier, had been at it with his own group, Gang Starr, for four albums and their latest, ‘94s Hard To Earn, had presumably satiated the public’s need for an album like this (Group Home members Lil’ Dap and Melachi the Nutcracker had even been featured on it). Furthermore, Premier was emptying his creative reserves by throwing tracks on seemingly every NYC rap album out at the time.

Small wonder then that this thing is maybe better than any Gang Starr album or Jeru the Damaja’s first two albums. Tellingly, the worst thing on it—“Serious Rap Shit”—is produced by Guru. Jaz-O handles another track; the solid “4 Give My Sins.” Beyond that, it’s all Premier, coiled and menacing—yet rough around the edges where needed—as ever. Dap and Melachi, meanwhile, prove highly effective foils, describing their surroundings with little to none of the egocentric stance that marred Guru’s lyricism.

15. Isaac Hayes – Hot Buttered Soul

Year: 1969

Ah, Isaac Hayes: accidental sex symbol and civil rights icon. He’d lingered behind the scenes at Stax-Volt for years, writing for Sam & Dave with his partner, David Porter, and releasing one album, Presenting Isaac Hayes, which was, according to label president Al Bell, a drunken joke. Then Stax lost its entire back catalog in a bad deal with Atlantic and, beginning in 1968, Bell set about replacing the entirety of it by recording and flooding the market with nearly 30 albums. One of these was a project no one expected to do anything at all; Isaac’s second album, Hot Buttered Soul.

Instead it was a surprise smash hit. With four tracks spread over 45 minutes, the album is a monster. Hayes, in what would become his signature style, essays Burt Bacharach and Hal David’s “Walk On By” for an awesome dozen-minute stretch. He then echoes early Funkadelic on “Hyperbolicsyllabicsesquedalymistic” (twenty years later, Public Enemy grabbed a piano snippet of this for “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos”). Just as huge was Hayes take on Jimmy Webb’s “By the Time I Get to Phoenix,” which has him delivering a spoken-word intro for the first third of the track’s 18-minutes; a holdover from his club days that was apparently enormously effective with women.

The rest is history. The Shaft soundtrack. Jesse Jackson melodramatically removing his hat at Wattstax. Chef on South Park. Scientology. But it all began right here, because someone forgot to read the fine print.

16. James Brown – Hell

Year: 1974

Collecting James Brown on Polydor (‘71 to ‘81) is a certain sort of madness—will you ever get enough? But this, along with probably The Payback, has to be in any record collection. Speaking to Wax Poetics magazine in 2008, Pete Rock said of Hell, “The entire album, the sounds, everything you hear is just pure energy.” Brown put the bang of a ceremonial gong between each track. Golden-era-of-hip-hop producers (like Rock himself) sliced the thing up like a Christmas turkey, which is clear the second you drop the needle on the A-side opener “Coldblooded”—you’ll think you just put on “Baby, You Nasty” by Lord Finesse and DJ Mike Smooth.

The thing gets thicker as you dig deeper; check the sick loping groove of the C-side closer, “Don’t Tell a Lie about Me and I Won’t Tell the Truth on You.” All of this culminates with a 14-minute take on “Papa Don’t Take No Mess” spread across the entirety of the D-side. Rock could relate; “It defined my father perfectly [Laughs].”

17. Kool Keith – Sex Style

Year: 1997

When Dr. Octagonecologyst, Dan the Automator’s album with Kool Keith, came out in spring 1996, suddenly everyone wanted a piece of Keith. So it was pretty amusing and awesome to behold what he came up with as his first solo offering, Sex Style, the following year. The cover was a slapped-together collage of Keith wearing a hot pink thong advanced upon by a prostitute or a stripper with a box of children’s cereal in the background and a big car, a motel sign, champagne, flowers, and palm trees displayed around him. The music contained therein matched this visual tableau.

With hooks like, “Yo baby, don’t rush it when I sit up on it” or “Make up your mind, who you want to pump the butt?” or “Regular girls, they’re so boring, regular girls could never turn me on” or “Keep it real, represent what? My nuts,” it’s pretty clear where Keith’s head is at. With creeping, bouncy production from KutMasta Kurt, he sounds completely comfortable; the titular style clearly suits him. He put out dozens of albums after this but none ever worked this hard.

18. Kraftwerk – The Man-Machine

Year: 1978

All ten Kraftwerk albums are worth checking out, but this one was where it all coalesced. They invented vocals over keyboards and drum machines—pretty much the formula for modern pop. You can hear it really happen right here on their 1978 album The Man-Machine. Six songs spread over one disc, three per side; it’s all over in 36 minutes—not a second of it wasted.

“The Robots” is the perfect soundtrack-that-never-was for the climax of Karel Čapek’s 1920 play R.U.R. “Spacelab” is as spacey as the title implies, while “Metropolis” should have been sent back in time 51 years to score fellow Prussian Fritz Lang’s film of the same name. On the B-side, “The Model” is something they probably could have invaded MTV with in the following decade with the right timing and promotion.

“Neon Lights” was just the kind of tension-releasing atmospherics the album needed, while there’s plenty of hip-hop DNA in the album closing title track (Jay Z picked up on that). There are other Kraftwerk albums that shattered precedents a bit harder than this, but The Man-Machine was the one where they proved they were, as Detroit techno legend Carl Craig said, “so stiff they were funky.”

19. Main Source – Breaking Atoms

Year: 1991

On the 1993 A Tribe Called Quest track “Keep It Rollin’,” Large Professor, who’d produced the song, threw in a plug of sorts at the end of his verse, advising listeners to “buy the album when I drop it.” He never did, at least not that decade, but at least we have this. Released two years before and boasting full-album production from Large Professor, Breaking Atoms belongs in any conversation about the standout albums of the golden era of hip-hop, but the dissolution of the group’s label Wild Pitch left it out of print for years; a collector’s item, albeit a dope one.

It’s difficult to believe what’s coming out your speakers when you crank tracks like “Looking At the Front Door,” probably the most infectious diatribe by a pissed-off boyfriend ever recorded; “Just a Friendly Game of Baseball,” an awesome crime narrative set to a creeping jazz sample; and “He Got So Much Soul (He Don’t Need No Music),” in which Large Pro traces the evolution of his talents from when he was “negative three months old” to now, all over a choice snippet of “Hey Joyce” by Lou Courtney. Also not to be missed is the historic posse cut “Live at the Barbeque,” which features the debut on wax of a young man who’d go on to big things; one Nasir Jones.

20. Meat Puppets - Meat Puppets II

Year: 1984

The day Michael Jackson died, June 25, 2009, I made my way from Chicago to Summerfest in Milwaukee solely to see Meat Puppets play. I got into the festival grounds and made my way to the stage I was looking for. Nirvana was playing on the sound system, which seemed to indicate I was in the right place. I sat on some bleachers and a stoned teenager sitting beside me asked me “Is this where the Meat Puppets are playing?” I said yes. He said “Are they the band that Nirvana covered on MTV Unplugged?” I said yes. He said “What album are those songs on?” I said “Meat Puppets II.” He said “What year did that come out?” I said 1984. This guy had found the right person to ask all these questions; maybe it was because I was wearing a Black Flag T-shirt. Four years later I was in a new job where most of my peers are 10 years younger than me. One weekend I went to see Meat Puppets again and on Monday morning they asked me what I’d done that weekend. I said, “I went to see the Meat Puppets.” They said, “Who?” I said, “OK, did you ever see Nirvana on MTV Unplugged?” They said, flatly, “No.”

And so the easiest way to explain who Meat Puppets are is being erased. Regardless, this album remains a triumph. Courtney Love once said she dismissed it as atonal noise until Kurt Cobain performed it for her in its entirety. An enviable privilege, but this shouldn’t have been necessary; especially when you compare it to their previous album, which sounds like someone howling into a wind tunnel. Here, the range of human emotion covered in just over 30 minutes is astounding. “Split Myself In Two” eases us in with a fairly standard punk vibe, as does “New Gods,” but then “Magic Toy Missing” is a frantic, weird country instrumental. “Lost,” which label mates Minutemen covered, “Aurora Borealis” and “Climbing” have an appealing Neil Young and Crazy Horse feel, while “We’re Here” achieves the emotive, ethereal sound and feel so prevalent in early ‘80s indie rock.

Three of the album’s songs are elevated to hits of sorts by Cobain covering them backed by the Kirkwood brothers on Unplugged. “Plateau” is sublime, particularly when it explodes into an epic walk home at the 1:41 mark. “Oh, Me” is a brilliantly understated ballad to oneself. “Lake Of Fire” is as dire as its title implies, albeit with an appropriate measure of absurdity (this “lady who came from Duluth” doesn’t sound too scary). After that it all ends with the one-two punch of the perfectly composed and executed “I’m a Mindless Idiot” followed by the aptly titled “The Whistling Song.”

21. Neil Young and Crazy Horse – Tonight’s The Night

Year: 1975

It’s an album overstuffed with storylines. Crazy Horse guitarist Danny Whitten had died the previous fall, followed by the band’s roadie Bruce Berry, both of heroin overdoses. It was with all this in mind that Young entered the studio to record a new album in late summer 1973, hot off of a by-all-accounts disastrous tour (immortalized on his first live album Time Fades Away) that trashed the goodwill of the American record-buying public that he’d built up with his breakthrough album Harvest.

What’s more, he didn’t release this until after he’d put out On The Beach, which, in hindsight, is the reflective comedown Tonight’s The Night needed. And somewhere around this time he recorded a now-mythical album called Homegrown that supposedly bridges all this perfectly and he’s never released it.

No matter; Tonight’s The Night stands as his best album. Young once insisted no one ever listen to it during the day and you can see why. It begins and ends like a drunken wake and in between has him relaying tales of characters with “bullet holes in his mirrors” who “roll another number for the road.”

Amongst all that we have “Borrowed Tune,” which, Young openly admits in the song, borrows from the Rolling Stones’ “Lady Jane”; signature mid-tempo rockers in “World On A String” and “Lookout Joe”; bleary-eyed jams like “Speakin’ Out” and “Tired Eyes”; and material not-too-dissimilar from Harvest like “Mellow My Mind,” “Albuquerque” and “New Mama.” The conceptual masterstroke comes in throwing in the 1970 live track “Come on Baby Let’s Go Downtown,” which basically amounts to having Whitten sing and play guitar at his own funeral.

22. Nirvana – Bleach

Year: 1989

It was the first Nirvana album to get the deluxe reissue treatment a half-dozen years ago (Nevermind followed in 2011 and In Utero in ‘13) and was likely a rude awakening for both new fans discovering the band through and old fans who may have forgotten what they really sounded like at first.

Krist Novoselic gets in the first word with a rumbling bass riff on “Blew,” which then blows the band’s debut wide open. Kurt Cobain’s gifts with melodies are already there, but the band is raw; they sound more like their then-peers Melvins and Mudhoney than what they’d later morph into (Dave Grohl wasn’t in the band yet; they record 10 songs with their original drummer Chad Channing and three more with Melvins drummer Dale Crover). Cobain will actually take a conventional guitar solo, rather than his later style of either simply playing the central melody of the song or sending a squall of noise through his amp.

Among all the riffery on display, some songs really stand out. “School,” with its repeated lyrics of “You’re in high school again” and “No recess!” well express how much he hated his education. “Negative Creep” is a great example of Cobain’s ability to mock himself and rock hard at the same time. “About a Girl,” written after Cobain spent an entire afternoon listening to Meet the Beatles! repeatedly, seems to drop from out of nowhere.

The song's expert inclusion in the band’s appearance on MTV Unplugged years later pointed backward to an earlier version of the band its newfound legion of fans likely missed entirely. And “Love Buzz,” the band’s first single, is actually a cover of a 20-year-old song by a Dutch rock band called Shocking Blue that somehow fit Nirvana like a glove and became a live workforce.

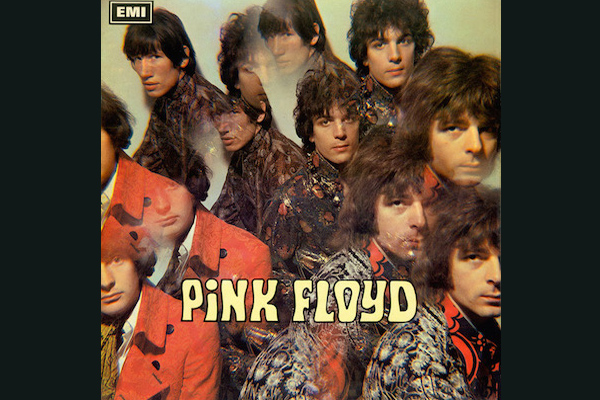

23. Pink Floyd – Piper at the Gates of Dawn

Year: 1967

Those who have only ever been exposed to Pink Floyd through classic rock radio or syncing Dark Side of the Moon with The Wizard of Oz in a darkened dorm room are not going to know what to do with this. Nevertheless, to a certain sort of head, Pink Floyd’s 1967 debut album is their best. They never did anything quite like it again and yet it charted a course for the celestial overtones and experimental ambitions that would stay with them for the next half-dozen years (their eventual crash back down to Earth was pretty ugly).

The reason it stands at such distance from the rest of Floyd’s catalog comes down to one man: Syd Barrett, the band’s leader, lead vocalist, songwriter and guitarist. His personality dominated their early work until LSD abuse and erratic behavior forced his ouster—he’d only contributed one song to their second album. Nevertheless, he’s on fire here; launching straight into outer space on the album opener “Astronomy Domine,” then starting the B-side in “Interstellar Overdrive.” Much of the rest of the time he’s showing off how much irresistibleness he can pack into three minutes or less. There’s “Lucifer Sam,” with its menacing, spy-theme of a groove; the elegiacal “Matilda Mother”; the child-like fun of “The Gnome” and “Bike”; the flooring psychedelia of “Burning” and “Chapter 24.” Barrett’s lyrics, while brilliant throughout, very much sound like the musings of a man working his way through too much consumption of psychedelic drugs.

An anecdote from the recording of the album holds that in March 1967, Pink Floyd was working on Piper at EMI Studios with Norman Smith, the Beatles’ former engineer, when he took them into Studio Two to visit the Beatles as they continued work on Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. At this session, John Lennon began behaving erratically, claiming to feel ill, and Beatles producer George Martin took him up to the roof of the studios for some fresh air and left him there. When Paul McCartney and George Harrison were informed of this, it “suddenly struck the two Beatles with force. They knew why John was ill—he was in the middle of an LSD trip”; this according to Mark Lewisohn’s 1988 book The Beatles Recording Sessions. “He was quickly fetched down to the studio before he killed himself.” Who probably dosed him? Syd.

24. Sly and the Family Stone – There’s A Riot Goin’ On

Year: 1971

Sly and the Family Stone could have exited the '60s with their legacy in music secured. They, under the tutelage of prime mover Sly Stone, had established intimidatingly high levels of musicianship, creativity, arrangement and social awareness. So of course they had to shatter the form and unravel completely to come up with something even better.

Stone recorded There’s A Riot Goin’ On’s 11 tracks himself at a custom-built studio in Sausalito and another one in his Bel Air mansion, bringing the Family Stone in for overdubs as needed along with musicians such as Billy Preston, Ike Turner and Bobby Womack for further assistance. By all reports his head was full of drugs; whenever he liked, he would bring in girls to sing over works in progress, telling them, “I’m going to make you a star,” then wipe the tapes the next morning.

The resulting murky sound has been hailed as a plus that fit the drug-addled mood of the music. “Luv n’ Haight” recast San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury as something that, at the dawn of the ‘70s, wasn’t too cool anymore. “Family Affair,” meanwhile, is a mid-tempo funk driven by Sly’s drum machine, stoned-sounding vocals, and Preston’s Fender Rhodes; a deep hit undeniable in any era. Equally riveting is “Time,” a fascinating oratory on the illusory nature of time from a man who was habitually late (his frequent no-shows at concerts caused riots, which is why the title track here goes on for zero minutes and zero seconds, because, Sly said, no time should be given to riots). Even a seeming throwaway like “Spaced Cowboy” is a thickly funky drum machine breakdown complete with yodeling.

When he finally decided it was done in the fall of 1971, Stone drove the master tapes over to CBS Records’ offices and personally delivered them to Clive Davis, who wisely didn’t tinker with them at all and promptly released the entire mess. It shot straight to number one on both the U.S. Billboard Pop Albums and Top Soul Albums charts and music critics continue to freak out over it to this day; proof that sometimes brilliance can emerge from chaos.

25. The Band – The Band

Year: 1969

People often confuse this with The Band’s first album. It’s an easy mistake to make, given its eponymous title. But Music From Big Pink, their album of the previous year (1968) makes much more sense as a debut. It’s brilliant, but embryonic, and it begins and ends with songs written by the man who had introduced them to mainstream awareness; Bob Dylan. You won’t find his name anywhere on The Band.

Instead what you get is an album that unabashedly goes through every twist and turn possible in American music. The album’s opener, “Across the Great Divide,” sounds ripped right out of Prarie Home Companion, but bear with us; it’s going to get way better! Levon Helm, the band’s drummer and tellingly its only American (the rest were Canadian), and an Arkansan to boot, takes over for “Rag Mama Rag,” with its country road booty call promising, “The bourbon is a hundred proof!” Band VMP Helm is on point again on the staple “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down”; nailing details of scenery like, “In the winter of ‘65, we were hungry, just barely alive.” Dude didn’t mean 1965.

Elsewhere, spell-binding slow-burners like “When You Awake,” “Whispering Pines,” “Rockin’ Chair” and “Unfaithful Servant” are jaw-dropping in their execution, both in the flooring sincerity with which The Band’s three lead singers deliver their vocals and in how keyboardist Garth Hudson surrounds the proceedings. If the keyboard line on a song needs to sound exactly like a cicada bug, it’ll do just that.

The Band rocks out plenty in the meantime. There’s the funky classic rock radio staple “Up On Cripple Creek,” the storm-foreboding “Look Out Cleveland” and “Jawbone,” which jerks in and out of different textures yet somehow makes musicological sense. Most astounding is “King Harvest (Has Surely Come),” which ends the album and reverts between a meditative chorus and barn-burning (literally) verses before settling on an understated solo by guitarist Robbie Robertson.

26. The Clash – Sandinista

Year: 1980

Legend has it that The Clash were only able to convince CBS to release London Calling as a double album if they told the company it was receiving a single album with a bonus 12-inch right up until the time of actual release, and then, for their next release, were only able to convince CBS to release Sandinista as a triple album if they told the company it was receiving a double album with a bonus 12-inch right up until the time of actual release. Any story like that’s gotta be true. Regardless, here we are: The Clash’s best album, recorded in England, New York City, and Jamaica in 1980 and shoved out at the end of the year, is a 36-track mess.

Sandinista begins hugely with “The Magnificent Seven,” placing The Clash alongside Chic, Kraftwerk, Some Girls-era Rolling Stones, and Blondie as contemporary bands who quickly got in step with hip-hop. “Ivan Meets G.I. Joe” is a shattering disco oddity. Perhaps one of the biggest songs on the album is “Lose This Skin,” which features Clash associate Tymon Dogg on lead vocals. Dominated by fiddle and propulsive, the song is about 10 years ahead of itself in the annals of English rock; no matter since it’s buried on Sandinista.

In between all that come snatches of punk, oldies radio, rockabilly and particularly a lot of reggae courtesy of sort-of producer Mikey Dread. Conventional wisdom about the album holds that it would have been a great double-disc album and a killer single-disc album. Whatever; that would have meant cutting out someone’s favorite song. Somebody somewhere out there loves the version of “Career Opportunies” with kids singing the words.

27. The D.O.C. – No One Can Do It Better

Year: 1989

In speaking to Rolling Stone magazine this year reflecting on the history of N.W.A., the D.O.C. summed up how the other members of the group basically built its star Eazy-E’s persona: “Between me, Cube, and Ren, shit, we had all the pieces we needed to make Eazy.”

Thankfully, he kept some for himself. After contributing lyrics and vocals to N.W.A.’s debut album Straight Outta Compton and Eazy-E’s debut, Eazy-Duz-It, D.O.C. finally got his own project on his 1989 debut, the classic No One Can Do It Better. It lives up to the title, with D.O.C. spitting motor-mouth lyrics that elevated what the West Coast was then considered capable of (he was from Texas though) over near-full-album production from Dr. Dre. The whole thing starts with D.O.C. asking, “Y’all ready for this?” Honestly, you might not be. Must-be-heard-to-be-believed moments here are “Portrait of a Masterpiece,” “Whirlwind Pyramid,” and “Lend Me An Ear”—up-tempo jams on which D.O.C. raps so much you wonder when he finds time to breathe (on “Portrait of a Masterpiece” he has Dre briefly stop the beat to do just that).

He kills it at a slower, funkier tempo on “Mind Blowin’” and the title track; material that wouldn’t sound out of place dropped straight onto Straight Outta Compton. There’s plenty of verbal interaction with Dre here too—like when he asks the producer to go to commercial so he can “take one of them long-ass, eight-ball pisses"—so this feels very much like an N.W.A. project with someone else center-stage.

Mere months after this came out, the D.O.C. was in a near-fatal car accident that crushed his larynx, rendering it difficult for the self-described “kid with the golden voice” to rap. Didn’t stop him; he kept ghostwriting, scoring five credits on Dre’s landmark The Chronic. That’s him on “The $20 Sack Pyramid” and he’s in the “Nuthin’ But A ‘G’ Thang” video, getting a large shout-out from Dre himself right before the snotty girl gets sprayed with beer. Vocal therapy and surgery has since partially restored his voice and he’s working on new music.

28. The Kinks – Lola Versus Powerman and the Moneygoround, Part One

Year: 1970

So you’ve heard all the hits like “All Day and All of The Night” and “You Really Got Me,” the latter either by The Kinks or Van Halen. But do you remember the episode of Family Ties in which Nick asks the minister if they can play “Lola” as he and Mallory walk down the aisle when the couple elopes? Unlikely.

The point is, after the Kinks were done hotwiring American blues into power-pop, pining for pastoral England and predicting the fall of the British Empire, they walked into the ‘70s with a big fat target for satirization square in their sights—life in a band. Fourteen years before This Is Spinal Tap, on Lola Versus Powerman and the Moneygoround, Part One, Ray Davies laid out the basic plot, taking on what it was like to deal with all facets of the music industry, from management and critics to contracts and touring.

Davies is particularly arch tackling the press. As he recounts his fictional band’s rise up the charts, he relays with surprise that, “Now the Melody Maker want to interview me, and ask my view on politics and theories on religion.” These are not things we should ask musicians about and yet we do it all the time. Touring, meanwhile, is simply summed by the sensation of knowing wherever you are, the next day you’ll be somewhere completely different, via mechanisms beyond your control, all expressed with the Kinks’ trademark epic yet understated charm, on “This Time Tomorrow.”

Like with almost any concept album, Davies strays off topic in spots. There’s the aforementioned “Lola,” the catchiest ode to a transvestite not written by Lou Reed, along with the silly-yet-essential “Apeman.” He ends the proceedings by concluding that he’s “Got To Be Free”; a rollicking, piano-driven number that sounds like the weight of the world has been lifted off of The Kinks’ shoulders. It’s a shame they never made a Part Two.

29. The Mothers Of Invention – Freak Out!

Year: 1966

This year, Frank Zappa’s estate released his one-hundredth album. All of that and he’s never topped this; his band’s 1966 debut album. Legend has it that when the Beatles were recording Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Paul McCartney was competing with the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, while John Lennon said of his efforts on the album, “This is my Freak Out!”

It’s understandable that the Beatles would take this as a reference point. Zappa set his sights on everything; the then-emergent hippie trend and square America’s reaction to it, the ridiculousness of romance at the end of the twentieth century, homogenization of perspectives on life and the sheer purposelessness of everything. And that was just on the first disc.

On the second (yes, their first album was a double album), the Mothers address then-current racial turbulence (“Trouble Every Day”) and then just get outright weird on “Help, I’m a Rock” and “The Return of the Son of Monster Magnet,” the latter of which was spread across the entire D-side. All of this was spectacularly well done, packed with earworms and legitimately funny jokes. Half a century ago, this must have been flooring; at least to those who heard it. We know one very famous Liverpudlian did.

30. The Rolling Stones – Some Girls

Year: 1978

A casual scan of the Rolling Stones’ discography likely holds that their early years were iconic and secretly adorable, while they peaked between 1968 and 1972 with their unbeatable four-album run of Beggars Banquet, Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers and Exile On Main St. It may surprise some to learn, then, that they slipped out one of their best albums ever in 1978.

It shouldn’t have worked at all. It was written as an extended ode to New York City, particularly its then nascent hip-hop and punk scenes, but recorded from October 1977 to March 1978 in Paris. The band’s last three albums had kind of sucked; they’d lost Mick Taylor, probably their best guitarist ever, and were still breaking in newly hired guitarist Ron Wood; Mick Jagger was further confusing matters by playing guitar himself; and Keith Richards was on probation for heroin possession.

And yet, track for track, it does work. “Miss You,” a street-sax-slathered nod to disco, was a huge hit and entered into the record Jagger’s perfect rap, “Hey, what’s the matter man? We’re gonna come around at twelve with some Puerto Rican girls that are just dyin’ to meet you!” “When the Whip Comes Down,” “Lies,” and “Respectable” really do summon up some of the fury of punks, then writing them off as dinosaurs, though Jagger takes the musical proceedings as an opportunity to lament “I was gay in New York, which is a fag in L.A.” and boast of “talkin’ heroin with the president” before identifying “the easiest lay on the White House lawn.”

On “Just My Imagination (Running Away with Me)” they pull off a Motown cover—which at their age risked looking lamely nostalgic (see their cover of “Ain’t Too Proud To Beg” released four years earlier)—with style, and turn in their best country send-up, “Far Away Eyes,” in a career full of them. “Beast of Burden” is one of their best ballads ever, while “Before They Make Me Run” is one of their best Keith-songs ever. Album closer “Shattered” fully earns the album’s association with hip-hop and punk while sounding undeniably like the Rolling Stones.

The title track inventories every type of girl you could ever possibly meet; it’s like Jay Z’s “Girls, Girls, Girls” a quarter-century in advance. Speaking to Rolling Stone magazine in 1978, Mick Jagger was asked to compare the song to the Beach Boys’ “California Girls.” Jagger responded, “I never thought of it like that. I never thought that a rock critic of your knowledge and background could ever come up with an observation like that [laughing].” Pressed, “You mean it’s pretentious?” he shoots back, “Not at all. It’s a great analogy. But like all analogies, it’s false.” Well then.

31. Tom Waits – Swordfishtrombones

Year: 1983

There are two sides to Tom Waits. For the first decade of his career, he was a singer-songwriter with jazz tendencies. Then something changed. Maybe it was recording an album of duets with Crystal Gayle in the early '80s that made him snap, or the influence of his new wife and collaborator Kathleen Brennan, who exposed him to Captain Beefheart; or his having just signed to Island Records, frequently the home of eclectic work.

Whatever the case, beginning with 1983’s Swordfishtrombones, audiences were introduced to a very different Waits—one more likely to sing something resembling a sea shanty while bashing on junkyard trash than a piano ballad.

He sounds like he’s on “Shore Leave” on the song in question, rolling into town with “a new deck of cards with girls on the back” before writing “a letter to my wife.” He does just that on “Johnsburg, Illinois,” a tribute to Brennan’s hometown. “In The Neighborhood” would be one of the most affecting songs of his career if it wasn’t backed by the saddest-sounding horn section ever and a lone drummer. Character study “Frank’s Wild Years” describes a couple in such detail it bothers to dwell on “a little Chihuahua named Carlos that had some kind of skin disease and was totally blind.”

There’s plenty of beauty to marvel at here, but there are also songs like “16 Shells From a Thirty-Ought Six” that sound homicidal. Waits has spent the rest of his career traversing the divide between the two extremes. It’s made him one of the most manifestly human singer-songwriters in history.