Sometime around the turn of the 2010s, The Alchemist moved back to his native Los Angeles in hopes of starting a new musical chapter. He was already a well-regarded producer, thanks to his work with rap royalty like Mobb Deep and Dilated Peoples and classic hits like “We Gonna Make It” and “Hold U Down.” But he was looking for something new.

While building his first LA studio, he simply wanted it to be an environment that was “comfortable for people to create,” he says. He wanted it to feel like “a sanctuary.” That’s all an artist can ask for, but the open-door policy he instituted at his new studio, deemed “the rap camp” for a time, did more than that. Alchemist recalls having a New Year’s Eve barbecue, organized by Chuck Inglish, which ended up turning into a week of music-making that forged artistic kinships since credited with defining a subsection of 2010s rap.

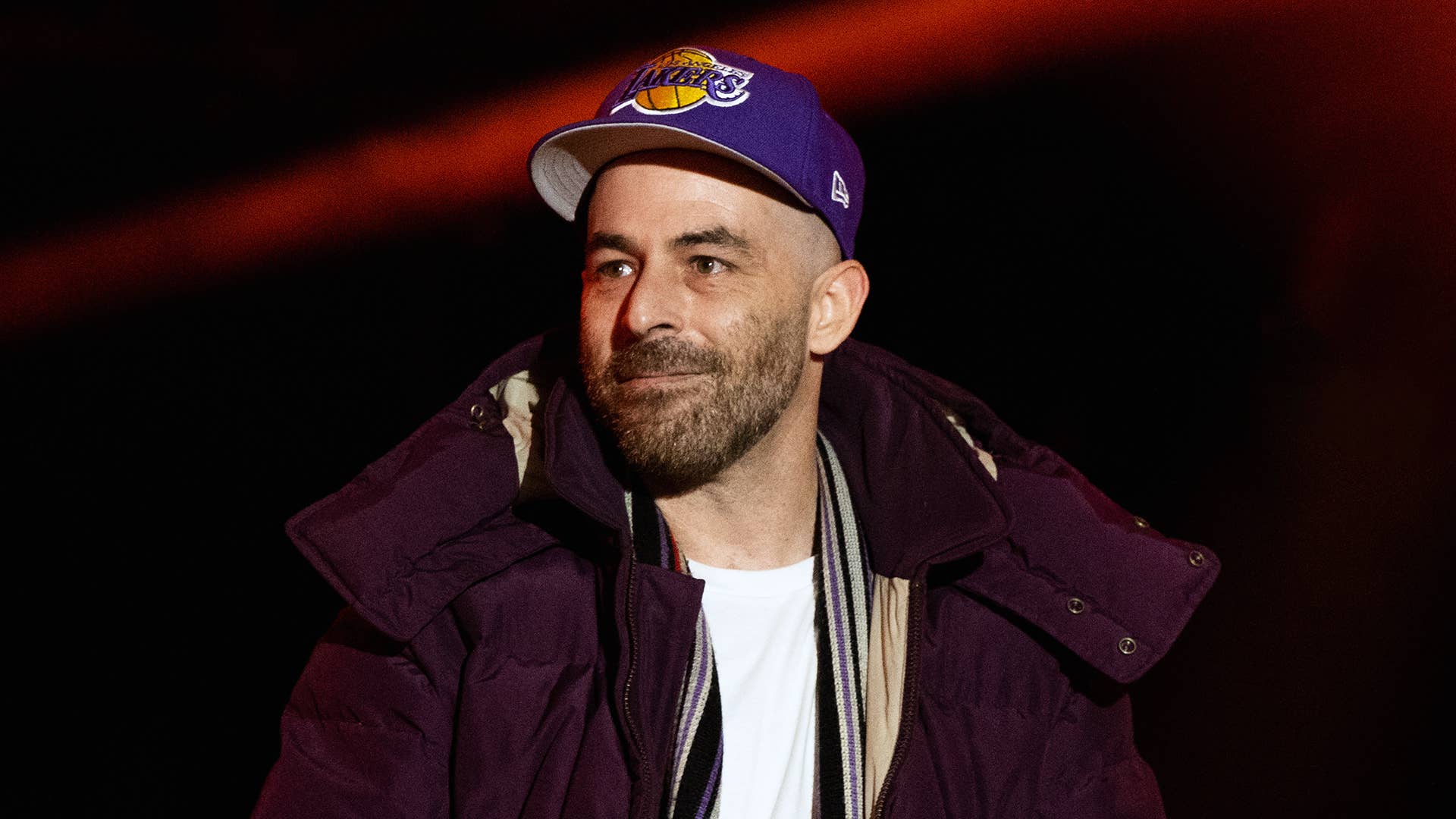

Rap fans can always be sure that three things are eternally looming: death, taxes, and a dope Alchemist collab album. In 2021, he dropped eight projects, including two with Boldy James, one with Armand Hammer, and a pair of This Thing of Ours EPs featuring a loose crew of talented lyricists he was connected with through his close friend Earl Sweatshirt. That torrential output earned him the distinction as Complex’s Best Hip-Hop Producer Alive for 2021 (you can see past winners and read the full explanation here).

Alchemist says he appreciates the honor, but he has no plans to wield it over his peers. After all, he credits fellow producers for helping to motivate him to lock in the studio every day and make music. He says also compelled to stay busy, because he’s his own boss at ALC Records, which saved him from a previous industry experience where his “fate is wrapped in the hands of A&R meetings, record labels, and radio guys.” Now, his fate is in his own hands, as he drops free projects, bolstered by creative merch, vinyls, and touring.

Complex had an extensive talk with the producer about his 2021 highlights, his thoughts on “underground rap,” how his craft has evolved over the years, and his 2022 plans (which already have him on the fast track to 2022 Best Hip-Hop Producer Alive contention). The interview, lightly edited for clarity, is below.

You were just named 2021’s Best Hip-Hop Producer Alive. How does that feel?

That’s pretty crazy. I mean, I don’t know if I can take that, because there’s a lot of great producers out there. I love the recognition. I mean, it’s dope that you care, but I can think of a lot of living guys that are pretty damn good.

What does that dignification mean to you? How much do you care about being perceived as the best producer?

I would never imagine myself that, you know what I mean? I try to be the best version of me. I can’t compare myself to anyone else. I get my inspiration from everyone else, so I often feel inferior. Some of the people that I look up to, I think, “Ah, I could never be that good.” I always feel weird with compliments because we do this for ourselves first, but of course we want to get the recognition, too. It’s always been awkward, just because I’m tempted to put the light somewhere else. Like, nah, have you heard V Don? Have you heard [these other producers]?

I feel like producers have a brotherhood, even more than MCs do. I’m happy to see other guys doing good. I’m not afraid to say I’m inspired by other producers that are existing. I feel like MCs may not want to give it up like that sometimes. But I love the opportunity that I’ve been given, and the fact that I’m in this era and still getting acknowledged. It gives me energy to keep going, because I feel like I’ve got a lot more juice still, even though I’m not a young guy. I love it.

I’ve got to give a lot of credit to the artists I’ve been able to work with, too. Because had I drifted off into obscurity and not connected with the right new young artists, it may not have given me those extra laps that get the next heat.

“I can’t ever stop and become a teacher, because I’m also still a student to a degree.”

In your recent interview with Idea Generation, you talked about the rap camp where you had an open door policy in your studio. You’ve worked with so many artists with distinctive sounds, but they’re all connected through you. How does it feel to be an integral part of a community of lyricists?

I never really wrote that on a board, like, “That’s my goal.” But I think that was my goal in the back of my head. I always wanted to have an environment where it’s comfortable for people to create and not pressure them. The studio is a sanctuary. Sometimes, when people fuck up the studio and it’s a mess or something, I’m always like, “Yo, this is a sanctuary. You’ve got to protect it. This is our shit.”

I always looked at old footage of the Beastie Boys when they made “Check Your Head,” and their studio was a certain way. It was a studio where everybody would meet and make music at. It inspired me to have a place [of my own], because all those years in New York when I had the whole run with Mobb Deep and everything, I never really had a studio. I had my crib where we would meet, and my apartment had a studio in it, but it never felt like I had one. I would go to see Havoc in Queens at their spot, and it felt like a real studio and everybody would meet over there. That was another thing that inspired me—having a place where you can start and end at every day.

You have a lot of collaborative albums with artists. When you’re working with an artist for the first time, how does the collaborative process work for you?

I approach each one differently—the same way as a painter would step to the canvas and try to do something different. Everybody is different. Human beings all have their different nuances and quirks. My process is to become friends first, or just to get to know a person and like them. If you’re a good artist, you’re really in tune with yourself, and you’re making music that is representative of you as a person. When I think back on a lot of the good music I made with people, when we first met, there was a moment where I was like, “I like this guy.” Either they said something or cracked a joke. We’re pretty funny. If you’re too stiff, that may not work.

Humor’s a big part of everything we do. You don’t always hear it in the music, but a friend told me that a long time ago. A very intimidating and respected person—I think their reputation would beat themselves in business—told me when they go in meetings they usually crack a joke real quick, just to break the ice. Because he’d notice that people would be on edge a lot, based on his reputation. So he was able to put their guard down a little bit. If someone doesn’t have a sense of humor, that’s kind of like, “...damn.” That doesn’t mean we can’t make good music, but I noticed that all my friends spend a lot of time laughing. Or we look at things in a certain way, which is the only way that artists do, or comedians do. We all have a certain way that we look at stuff, which gives us our perspective.

I think that’s part of it: to become friends with the person, or just get to like something about them. Even if I don’t like them, maybe I could respect something about their creative process to go, “Well, he ain’t the funniest guy, but man I really respect how he gets his ideas and puts them together to make songs.” Or, “I like the type of beats he picks.” Whatever it is, I start there, and build some type of ground that we could get on. Then the music usually comes easy after that. At this point, I feel like I’m lucky enough that if I’m linking with somebody, they fuck with me. I’ve noticed that I don’t have to go too far out of what I think will work.

It’s funny because what you think will work for people, doesn’t always work. When I would work with new artists, I’d go check their stuff out and I’d be like, “OK, I got it. I know what he likes.” But a lot of times I would be wrong. It’s like coloring in the lines too much. If an artist has a [certain] style and then you collaborate with them and you present something that’s pretty much indicative of a style they’ve already done, it almost makes the artist defensive. It’s almost like, “Oh, you know me so well. That’s the type of sample I want to use, because I used it two years ago on another joint? You think I’m going to write a song like that, because I wrote it before?” I think as artists, we all have that little knee-jerk reaction when people do that, but I think it’s natural for us, because that’s what we have to go by. I have to judge on what you’ve shown me.

A lot of times, I get upset because people want to put me in a category based on what I’ve done: “Oh, wow. He makes these type of beats.” And sometimes I get mad, like, “You don’t know the corner I’m about to turn.” But why would I get upset with them? They’re just basing it on what I’ve shown them. Until I show them otherwise, I’ll continue to be put in a category that is more related to what I’ve [already] done. I think that’s a mistake I’ve made in the past when I was trying to pick these samples. As you get into it, you start to learn more about what fits. Because I do a lot of different styles when it comes to making beats.

I think the key is to figure out which ones fit which artists. Sometimes they will be like, “Oh man, why is he doing that style?” I think as a producer, it’s your job to blur the line. Just like Madlib and Oh No. They both fucked my head up so many times, playing me things that showed me you could do different things and not be stuck in one genre or style. As a producer, that’s a way that you won’t get bored either. You can just keep switching up your modes. Try a different style.

“Mac [Miller] taught me a lot of tricks that I still use with Pro Tools. He was really clever with the sh*t.”

You’re renowned for particular sonics and vibes in your music, but you do experiment, too. Would you be amenable to working with an artist that nobody expected, like a Gunna or YG?

There’s no fences in this rap shit with me. There’s no backstage. There’s no VIP area for me. I want to go everywhere. I want to do it my way, of course, but at this point, I like surprising people. Once you get a style that they can put their finger on, it’s not fun anymore. As you get further in the game, the goal is to challenge yourself to go outside of your comfort zone, but don’t turn into a complete fucking weirdo where people are like, “Damn, he’s doing bad because he’s been good for so long.” You know what I mean? “He’s doing bad on purpose.” I don’t think that’s the goal, but I do think there’s ways to challenge yourself to go outside of your comfort zone as you get older, and make shit that’s still dope in some new territories. That usually happens when you bring other people in.

When you bring new energy in, you get a different outcome. Any time I collaborate with different people, I get something out of it. I don’t know exactly what I am. I’m constantly learning new styles. I couldn’t even describe what my style is to you. Whereas a fan or listener would be like, “What? You’re tripping. This is your style.” But that’s only based on what I’ve shown them already. I’m telling you, I can listen to a beat from a year ago, like, “I know new things already.” I’m always hanging around people who put me up on [new] tricks.

It was just Mac [Miller]’s birthday. God bless. Mac taught me a lot of tricks that I still use with Pro Tools. He was really clever with the shit. Last week, one of my engineer homies came over here and showed me something, and I’m like, “Okay, that just changed the way I’m doing shit from here forth.” I can remember when I would learn new things and implement them into my workflow, and it would create a new style or a new sound. I can’t ever stop and become a teacher because I’m also still a student to a degree. I think there’s things people could learn from me, but I would never be the all-knowing guy, like, “This is how you make a beat. This is how sonics should be.” I’m still discovering shit. I don’t think you could ever master it entirely.

[It’s important to] continue to learn and implement new things into your style and your workflow, to create a [new] outcome. [But] if there’s an underlying thing in all the stuff I made that someone could pinpoint, well, then I did it. Then I could say I did it. If you could listen to Cycles, the project I just put out, and listen to a Boldy James album or listen to a Dilated Peoples beat from a long time ago or the Grand Theft Auto stuff. If there’s something similar in all that, then I feel like I did the right thing.

In what ways do you think your production style has changed over the years?

I started paying way more attention to the details and sonics in the last 10 to 15 years. Once I got an actual studio in LA with a sub[woofer], I started paying more attention to things that I didn’t pay attention to in the past. I would listen to old things and be like, “Damn, I didn’t even realize that. I could change that and make it better now.”

But I hate producers who say that all the time, so I don’t want to fall into that trap. I don’t want to be that guy who plays a beat for you, and every time, he’s like, “Oh, I can fix that snare. I can make the fucking hi-hat a little bit better.” It’s like, relax. I understand it, because I am that guy a lot, but I try to not be, because it’s annoying. And the other ways that my style has changed over the years? I feel like I got more free mentally.

I can’t really pinpoint when my style and technique changed over the years. But in the earlier days when I was in New York, I started to develop a style that was based on the people I was inspired by, and it was based on the ASR 10. I had some fences up, and kept myself in a certain area. There were things I wouldn’t do. When I did “The Realest” for Mobb Deep, I was embarrassed by it, because it was a one-shot, a loop. It was just like a two-bar loop. We gated the kicks and snares out of it and added it on the tape. We had too much tape at the time, and the engineer Steve Sola did a lot of work because it was just a two bar loop. But at the time I couldn’t accept it. The beatmaker side of me wouldn’t accept it. Like, nah, too easy.

“When I got older, I started wanting to appeal to people that like music, live a regular life, and don’t care about snares. People who care about snares, I’m one of them. I get it. But I didn’t want to make music just for them anymore.”

After the success of that record and how people loved it, it made me realize that it’s not always about your kicks and snares—it’s your decision-making. Sometimes it’s a sleight of hand. It’s not a how-to video. Sometimes it’s like magic. The record gives you a feeling where you open up the hood, like, “Damn, there’s only two wires connected. There’s not even an intricate system in this engine.” You still enjoy the ride. Whereas, [when] I got older, I started wanting to appeal to people that like music and live a regular life and don’t care about snares. People who care about snares, I’m one of them. I get it. But I didn’t want to make music just for them anymore.

I felt like I had a lot of shit to prove in the early years. Even after we did the Mobb Deep stuff, and “The Realest,” and I was on their album, I was a new guy out there and I felt like I needed to prove myself still. Then when P[rodigy] used “Keep It Thoro,” I felt like that was a crafty kind of beat that I put together, so I felt better and I felt like I wasn’t a one-hit producer. Not that “Realest” was a hit, but the streets were fucking with it, so I felt like I could just be a guy who found a good sample. But I felt that once I did “Keep It Thoro,” it helped solidify me, like, “Okay, this guy’s dope.”

Over the years, I started letting go of that, [although] I still have things to prove always. You never feel too comfortable, like you’re just the man. I still want my peers and the guys that I respect to be fucked up when I drop something. I want to get a call from DJ Dahi. I could name a hundred guys that I respect, whether it’s a sample or a chop or a replay, whatever it is, I just want them to be inspired by it as well. But the most important thing is making records and songs that are great. Madlib and Oh No really helped me without even knowing it. I didn’t ask for their help, but by just being themselves, they gave me a lot of confidence.

I looked up to producers who had no end game other than making beats for rappers, going to studios, and selling beats. It seemed like that was the end game for all my heroes. It didn’t seem like there were any other ways. So over time, I started to feel like, “Wow, you can do an instrumental project. I can be expressive with production and not always have to depend on the MC.” Or like J Swift… Do you remember him?

I’m familiar with the name.

He was a producer in the ’90s. Legendary. He produced Pharcyde’s first album—all of Pharcyde’s music—and was basically a part of The Pharcyde. He was one of the first guys I was around when I was a teen, because I used to hang with The Wascals. They had a big mansion in Hollywood and J Swift was the producer. He had a big afro, he was a real vibe guy, and he made crazy beats. I went over to his crib one day and he wasn’t there. Then he came back after the weekend, and he had his hair buzzed. His afro was gone, and I’m like, “Yo, what happened?” He’s like, “Man...”

He had gotten arrested on some really stupid shit. It was like a parking ticket. He said he got caught up in the system for three days, and had to cut his hair in jail. He was back at the crib, really depressed and upset that he had to cut his hair. Then he turned his drum machine on and started making this beat. I think it was a Bob James sample. It was really dark and moody, and he’s like, “Yo, this is how I feel right now, man.” It fucked me up as a kid, because prior to that, all I knew was making beats for rappers to rap to. And he literally made a beat that was how he felt. He didn’t say he was going to give it to anyone to rap over. I always remembered that, like, “Damn, that’s a trip. You could make a beat how you feel?” I never even thought of that. I just thought, “Yo, make some dope stuff that’s like the stuff you listen to, for a rapper to rap.” Prior to that, I wasn’t really being too expressive.

As a producer, your fate is also wrapped in the hands of A&R meetings, record labels, and radio guys. There were years where I’d do interviews and they’d ask, “What do you got coming?” I’m like, “I can’t really say, because I don’t know if the sample’s going to clear. I don’t know if the album’s getting pushed back, or if radio’s not responding or this.” Your destiny was not in your control, creatively. That used to upset me and started worrying me. I came into this game as a rapper first—I was a young kid in a group. Switching to being a producer for hire, and having success, it was like, “OK, where’s it going to go?”

To the world, if you’re a beatmaker or producing those albums, you’re as good as your latest joint on whoever’s album. Let’s say you’ve got three or four placements, and you’re waiting to see what happens with these albums, and a year passes by and nothing comes out. People might think you haven’t done a beat for a year. Perception is a trip. I started feeling like I was copping pleas in interviews, like, “No, trust me! It’s coming!” I wanted people to know where I’m at creatively, but I couldn’t.

This was prior to social media and Instagram. Now, if I want somebody to know where I’m at, I’ll just go Live and play a beat. Or I’ll play a snippet of a new Roc Marciano song I’ve got or a Prodigy song we haven’t dropped. But there was a time where I really felt like, “I can’t live like this.” I need to bring people up-to-date to where I am creatively, and not be so behind it all the time. That was a major thing for me—doing my own thing. Being able to just drop at your own time and control your shit is a great feeling.

As you made that breakthrough, you helped other artists shift their own models. Boldy James was just saying he feels like he’s at a great point in life, and when you worked with Gibbs, y’all had a Grammy-nominated album. How intentional are you about trying to use your esteem and respect to help shine a light on deserving artists?

As much as I can, but everybody has to walk their walk and do their journey and go through it. That’s one thing I had to learn the hard way. As you get older, and you’re around young guys, you’ll see similar things that have happened to you.

Your first reaction is to be like, “Yo, listen, don’t do it. I was there. I went through the industry. So-and-so went through the industry. We did the majors, and then you’re going to go through this whole thing. And then some of it’s going to be good. Some of it’s going to be bad. You’re going to get off and you’re going to end up where I’m at now. Skip all that shit. Come over here right now, and let’s just do it.” But it doesn’t work that way. Unfortunately, everybody has to take those steps in their own way. Having me as a reference point is good, and they can use my notes, but they’re still going to have to go through it. What I went through is not exactly the same as what they’re going through.

We’ve all had that period in our career where we were kind of lost, and going through the motions of the music industry. And that’s where I like to speak to some of the guys, like, “Yo, just be conscious of that. I’m not telling you not to do it. Take my playbook. Look at these notes. This is shit that happened before. Just refer to the manual, bro, because a lot of us went through this shit. Everybody’s going to tell you what you want to hear at first. They did it with me. They do it with everybody when you come into it. And then later on, what I’ve discovered is, it’s never going to be the way you want it. If you want it done, you’ve got to do it. That doesn’t mean not to have a team, but I think you need to start first. Build your shit up the way you want to do it.”

I know a lot of creative people, and we’re control freaks. I have to see certain things all the way through so I can be happy with the end result. But over time, I find people who I can implement into my formula, who can do certain things for me so I don’t have to do everything. If you get the right people, that’s the goal. [You want] to build that team over time, but I think you still need to be the brain of it.

What I’m more concerned with is telling some of the younger guys [who are in label deals], like, “All right. Don’t jump out of the ship. These guys are still here with you right now. Let’s ride this and do what we’ve got to do to keep your brand the way it should be until your deal is up with these people. Then you can take your shit on your own and do it the way you want. Make that transition smooth, instead of ‘Fuck the label’ when things start going wrong. Try to make everything work until you get to a point where you can be more hands-on with it. There is a value to having people spend a lot of money on you.” I think if you have a goal and a long-term plan, that’s what’s important. I always try to have a nice little plan ahead of me.

“I’m not with blanket sh*t: ‘Underground is all good, and commercial is all whack.’ I am not the flag-holder for everything underground. There’s good and bad in every category.”

What do you think about the term “underground rap?” I wrote a story about it last year, and when I talked to Slug, he was prideful in the idea of representing the underground, whereas when I talked to Mavi, he was indifferent about being categorized. Where do you stand? What does that term mean to you in 2022?

I don’t even know, man. I hate labels. I hate names and terms. I don’t like the name. It alludes to the fact that we’re underneath the ground, in the sewer, making music or something. Do I like underground music? Hell yeah. Because you’re really [talking about] people who are doing things their own way.

[But] I understand Mavi’s take, too, because he just toured with Babyface Ray and Jack Harlow. Of course he doesn’t want to be considered “underground.” Nobody wants to be underneath the ground, transmitting their music to the people on top of the ground. You know? So from a literal perspective, it’s like, “Nah, man.” But what underground music represents when you unpack it and go, “OK, what is this?” There’s some good shit.

Let’s also say this, I’m not with blanket shit: “Underground is all good, and commercial is all whack.” I’m not that guy, man. I am not the flag-holder for everything underground. There’s good and bad in every category. Sometimes I think I get confused for that guy, because of the type of music I make. I like some commercial shit, and I like some underground. I like what’s dope to me. I’m not going to just write off a whole style and be like, “Oh, commercial.” And people are like, “Oh, he’s got to like it. It’s rap in the underground.”

I think people have got to get off that shit, and stop putting everything in categories. That’s why I like seeing a tour like Jack Harlow, Ray, and Mavi. Whatever promoter put that tour together, salute. That’s dope. I think we underestimate these kids. It’s the older guys. We know so much, so then we start trying to categorize and catalog everything. It’s like our brain is a fucking record store.

I guess I took both sides on that answer, because I understand what Slug is saying, and I love the music that comes out of it. I just always feel like the word “underground”—it’s like it gives the wrong idea to the girls. We’re not trying to scare the chicks. [Laughs.] Are you kidding me? It doesn’t mean we don’t like women and all that. We’ve got to fix that.

Your response is in line with how I feel, as well as a lot of the people I talked to. It’s kind of ambiguous. And with categorization comes people putting limits on you.

Yeah, exactly. I think it’s a natural human thing for us to do. We want to understand things and organize them, so I don’t put people at fault for it. I just think it’s a weird, human thing that we do in the world, but it really doesn’t matter. I think some of these good artists now are melting all the genres anyway, especially the big commercial ones.

Yeah. Like, you’ve got Drake rapping over drumless loops. What does underground really mean at that point?

Exactly.

Earl Sweatshirt had two tracks on This Thing Of Ours, and you two have had a lot of collaborations over the years. Can you speak to the relationship y’all have, inside and out of the studio?

That’s my little big homie. Earl’s special. Anyone who knows him knows he’s a very important person in this whole system of rap music, and Los Angeles hip-hop culture in general. He represents a lot.

I’ve got him by probably 20 years, but we hang like we’re in the same grade, and it helped me a lot. He has an old soul and he’s really like a very wise, young man. I think we share a lot of things personality-wise, and stuff related to our lives. We both had a kid around the same time. That’s like my brother. Musically, he is very important. I think he’s a style father, somebody who forges paths for this rap shit, and he’s definitely a leader. But as a person, he’s just one of my favorite people, and one of the closest homies of mine over the years.

I think our relationship is exemplary in a way that could help mend the generation gap that exists at any given time in music. I’m way older, and he’s much younger, but there’s this common ground we meet on. He’s putting me up on shit. I’m putting him up on shit. And it’s not always me showing him the old shit and him showing me the new. He’s showing me M.O.P. songs I didn’t know about. It’s really just sharing and standing on the same ground. It’s helped me so much, as far as learning how styles have progressed, understanding the new styles of music, and just not turning into a bitter-ass old man.

[It’s important] having the young guys around me that I can trust, so I can have an understanding of the styles as they progress. And it’s [important] to have a place where we could meet in the middle, because there’s no reason why that generation and the older always have to have this standoff. The music is going to change. I always wonder if Grandmaster Flash and the Sugar Hill Gang—did they not like it when Nas was coming up? Was it like, “Oh, nah, nah! Rap has changed!” I always think about just moving the gap down to different generations and studying it. I think my relationship with Earl is important, because that’s a way that my generation and his is meeting in the middle when we do music.

“My relationship with Earl is exemplary in a way that could help mend the generation gap that exists at any given time in music. I’m way older, and he’s much younger, but there’s this common ground we meet on.”

Do you two have any projects coming in the near future?

Yeah, we have a pot that’s been bubbling. We have several things in motion. I’ll just say that. But stay tuned.

How did the idea to put that YouTube album come about? That’s such a brilliant idea to me.

Forward thinking. Drugs. Just thinking up out of the human box.

There’s a popular narrative that artists like Earl or Gibbs or Griselda represent a “revival” of lyricism. How do you feel about the idea of a “revival of traditionalist rap?”

Corny, stupid. They’re acting as if it went somewhere. You guys just stopped paying attention. This shit didn’t happen overnight. It’s been a progression. Like, Roc Marci was getting busy in 2001. It was a slow progression.

We’re all students of music. I don’t think any of us are trying to bring back a style. I think that we’re enriched in a style that is classic. When artists are really entrenched in a [sound], [people] move on and [the artists] get stuck in that era. Like reggaeton was when it was then, or crunk was what crunk was then. Then it moves on. I don’t think what we’re doing is like that, in that way. I feel like it’s been gradual and there have been a couple of nuances that got added into the soup.

Somebody like Roc Marci started just saying, “Fuck it, I’m going to rhyme to the filet. I’m not even going to put a drum on this shit.” Sometimes it was just because he wanted them to hear what words were being said. Sometimes it’s because he just didn’t want to—he ain’t got time for that shit, and the loop sounds nice. I think there were little things that happened, and now people look at it like it was this intentional soup that was created to create this underground sound. But it was literally a necessity becoming the mother of invention.

Samiyam, one of my favorite producers, has this style that is imitated. You could look online and see people making Samiyam-type beats. I don’t know how to describe [the style]. It’s very messy and not quantized and perfect, but it’s amazing. And I remember talking to him about it one day, and him telling me, “Yo, I was trying to make DJ Premier, Pete Rock, perfect type beats.” But with the machine he was using, and the way he could do it, he did it by hand. And that’s how it came out. Then it became his style. Now they copy it, and it’s funny.

Sometimes I feel like when people say “revival” or “it’s like that old shit,” no. It’s happening right now. Griselda’s happening now. Freddie Gibbs is happening now, Roc Marci. These are all things that are happening now in real time. If the sound of it is reminiscent of something old, well, so be it. I think there are so many things that add to it.

I was talking to Jay-Z one time, and I told him that I thought “Dear Summer” was one of the first joints that’s kind of like what we’re doing now. I also spoke with Ghostface before, and told him that when he was rhyming over the Delfonics. He was doing it early. And if you really want to get to it, [Ghostface and Raekwon] were rhyming over the whole filet of a record, or like an undercooked loop or something, even prior. So I think it was gradual. And I don’t think it’s a revival. I think what we’re doing now wouldn’t have been done that way. Like, the way Griselda took the things that they did and added it to their soup: Let’s get the wrestling stuff. Let’s slow the beats down with Daringer. Let’s add the ad-libs. That made it special and unique. I don’t think it would’ve been done that way back in the day.

There’s just certain details to how we’re doing it. Is it inspired? One hundred percent. Are we using samples? Yes. I don’t know how to feel about that shit, but I mean, I like that it’s getting attention. When I started seeing Westside Gunn’s neck getting really getting heavy, I was loving it. Because I started seeing other rappers who had to pay attention to him. This perception shit is funny, man. All that fire music he was doing, but once he started making that neck heavy, it was like, “Hold on, who’s this guy?”

Sometimes what we do, they would call it “dusty.” Like, are you crazy? Why is it dusty? Because it’s not like it came out of a keyboard? Or it doesn’t sound like it should be being played in a club in Las Vegas with those synths that are sizzling? That would get confused. But there were reasons why this became a lucrative business. We found ways to make what we’re doing lucrative. By virtue of merch, touring, lifestyle, adding onto it, and doing it the way somebody like Westside really did it. So I do like the fact that it’s getting the attention it’s getting.

One project that exemplified the freedom you spoke of is Haram with Armand Hammer. Can you speak to the freedom you had to create outside of the cultural norms?

I had just come off of Alfredo and all the success of that. First, I called Roc Marci, and I told him, “There’s nobody I’d rather do a whole album with than you after this.” And we started work on a record that’s coming soon.

With Armand Hammer, Earl is the one who put me onto their music. We connected at first through Billy and it felt like a challenge, because I was at a point where I was like, “How did I not know about this?” Just in the world it was in, and the groups we would put in with them, I respect but maybe wouldn’t always be producing for. But when I listened to Paraffin, it just spoke to me right away. That was like, “They are the true essence of art.” The same way I feel about Brownsville Ka.

I thought it would be a dope challenge for me. I did Lulu and I did a Boldy album, which each have the style that’s more comfortable to what I do. I felt like there was something I could do a little different with them, even production-wise. Listening to their shit made me want to do something different.

The only way to get a new result is to bring in other energy. They’re adding new energy. It’s like having co-producers damn near. They have a lot of input. Both of them are very much involved in the making of their records. They don’t just pick a beat and rap. So I felt like I was getting different inputs, and I knew I would get a different outcome from it. After Freddie Gibbs and Alfredo, [I told myself] I’m not going to do what I would’ve done when I was younger and think, “I’ve got to go bigger now.” Of course I want to go big, but I want to follow this shit up with things that are dope now that I have a spotlight, or people are somewhat paying attention.

A month later, you released your This Thing of Ours EP. How exciting is it for you to work with more up-and-coming MCs?

I think it’s all about the right ones. It ain’t much different than an A&R or somebody. I want to gamble on the guys that end up doing something, and work with them early. Like, Earl brought Vince Staples around early. I remember the early days when Vince was around, when he was young, before anybody knew about him. Earl was already saying, “Yo, Vince is the best.” And we knew over at the studio early on, that he was good. Not that I was a part of his success in any way—he did it on his own—but [it was great] seeing it all develop right there.

I look at it like banking and gambling on the ones that are dope, and that gives me another lease on life every time. Thebe was on the first and last song on This Thing of Ours, because I wanted him to be my co-pilot on that tape. Because really, these are all people I met through him. Sideshow, Mavi, Maxo, Navy Blue, and everybody were guys I met through Thebe. So I was like, “You know what, if they were a whole crew, I would’ve done it.” They were like a loosely knit crew. It wasn’t like Native Tongues or something, but it was a group of guys who were all dope and on a different wave than some of the street shit that I work with.

Part of my intent with This Thing of Ours was to show that all these guys do something, and later you can trace it back and be like, “Ah, it was early.” That’s why I had Earl on it, because how could I take any of the credit? He’s the one who put me onto all this shit. I definitely want to find the ones that are young and dope, and if I have a name that could help, perfect. Like J.U.S, who’s down with Bruiser Brigade, we just did a joint recently. I’m going to keep working with anybody who I feel is dope and fits these beats, who I could shine some light on. And if I could [also] do records with some of the greats that I still haven’t done records with, I’m happy.

You’ve mentioned wanting to collaborate with Jay-Z before. Is that any closer to happening since then?

I feel like it always gets a little closer. We’re in communications. We live in the same city. I think it could happen, man. I really do. It’s one of the last things that is very important to me that I really care about. I think it’ll come eventually.

Are you currently working on something with any of those artists on your bucket list?

Yes. There are two that are like, “This has to happen.” And I do have a lot of Prodigy music, and I’ve been listening to the songs lately and making sense out of it. Who knows?

Do you ever feel pressure to continue being so active?

My goal is to do things moving forward that could maybe even belittle what I’ve done in the past. I don’t want to use my past as a test. I feel like I’ve done a lot of great things and reached crazy heights that I don’t think I ever thought I would, but I look forward to the future. If that’s the label, whatever it is. We’re at a new phase now where I really want to take everything I’m doing further. I’m at a phase where I’m not complacent again. I’m not riding off into the sunset.

It’s going to take some time to do that. Nobody knows what I might have in my mind for my future. So I manifest it and do it, and then they can understand and relate to me. It’s a great history. I love it. I’m still here and it’s a blessing to be able to still be here. I want to take advantage of it, and I want to get better. I still make beats every day, and I don’t know too many guys from my generation who are still doing that. I’m a father now, too. But as these new challenges come, I’m into setting up new challenges. I have a couple of homies that died when I was in high school and I think they just looked over me, because every year, good shit [happens] like the Nipsey song with Dre on the Grand Theft Auto that just came out of nowhere.

Things like that always happen, and they remind me, “Yo, just keep cutting, doing your shit.” I get what I need to get out of it and stay motivated. It will always be a young man’s sport. But I look forward to my son hating my music. That’s my goal. I want to be that father where he’s showing me the new stuff. And I’m like, “That’s dope.” I want to like their shit, but I don’t want to be that dad that gets so inspired by what their kid likes and starts making shit. My son will never be my A&R, if that makes sense.

I will learn from him. I want to understand everything they’re doing, but if he likes my music, I’m in trouble! I’ve seen that happen to guys. Like, their kids turned 15 or something, and they start telling their dad, “Nah, dad, that’s dusty. You’ve got to do this. This is what’s out.” And then the dad starts getting swayed by their sons, like, “My son’s my A&R.” I don’t ever want to do that. My point is, it’s always been a young man’s thing, so we haven’t gotten to a place yet where you can have old [artists.] I think Jay was the first to try to do that. And I think he did it. He’s the only one—we need more. We need more guys in their older era who are accepted to do music that the younger guys may not play, but they [get] respect. And as we get older, we can’t worry about getting approval from the younger generation, meaning, “Where is this style going to go?” I think we’re going to get a new generation of kids who are inspired by it. The catalyst never reached the benefit, right? I do feel like everything that all of us are doing on a bigger scale could be a catalyst movement.

Whether Conway or Marci or any of us reap what we really feel we deserve for some groundwork that we lay down, I’m more concerned with the 15-year-old kid that’s listening to that shit. The 13-year-old kid whose friends all like NBA YoungBoy or the other stuff, and he don’t like that shit. He likes this underground stuff for whatever reason, and he’s getting inspired. Also, he likes new stuff. I feel like there will be a hybrid of what we’re doing now in the future. It’s not going to sound exactly like what we’re doing. It’ll have some elements of it, and when they do their interview with Complex, they’re going to say, “Yeah, I was 15 in 2020, listening to Freddie Gibbs and Griselda, and all my friends were listening to something else.” It’s going to change, and I don’t think the beats will be the same. But I do think we’re laying out breadcrumbs for a new guy. The same way when the older guys heard Kendrick, they were like, “It ain’t the same,” but we could tell it’s entrenched in some type of style. It wasn’t hard to get behind and you could hear the influence of a different generation—but it’s all new.

I think it’s going to happen. That’s why I say my relationship with Earl is good. I just did a DJ tour of Europe last November, and it had been three years since I’d done it because of COVID. Prior to this, I would play all my shit that I produced, and there usually wouldn’t be anybody under 30 in the fucking crowd. It would all be older people—people who grew up with it. Now, I got the Griselda set, I got the Earl songs, I got This Thing of Ours, and I did the show, and I’m like, “I wonder what’s going to happen.” When I saw the crowd, I saw kids that were in their 20s, and then I saw the guys that were 35 and 40, so it was this new mixture. When I played all the new shit, the kids went crazy. I’m like, “Oh, this is perfect. Now we’re mixing it all up.” Eventually, some of these young guys would take some of the older sauce, mix it up and make a new thing.

“[Projects with Earl Sweatshirt and Roc Marciano] are both coming this year. Now, I’ve made my bed.”

What do you have coming up for 2022, musically and otherwise?

Off the top is the new Curren$y project, and [Benny the Butcher’s] Tana Talk 4. I got a song with Kool G Rap, a new Craft Single that we’re about to drop. This tour starts in a couple weeks, so we’re all going to be on the road together. It’s basically like taking the studio on tour.

I’m working on a series right now: The Alchemist Presents tour. It’s going to be a tour series, and it’s going to be anything that I do with the studio or with the merch. I have these three different worlds; the studio, the online sales, and then the stage, and they all do really well. So I’m like, “Why don’t I bring them all together?” I started thinking, “Man, all my friends are the dopest guys to me.” So I wanted to start doing a series of Alchemist Presents concerts where I’ll be featuring different combinations of guys that I already rock with. It may be Freddie Gibbs and Boldy in whatever city. Different combinations. Also, I want to reach outside of people I only do whole albums with, and curate shows that are similar to what goes on in the studio. It’ll be like Earl and Benny here, just randomly. So stay tuned for that as well.

You mentioned working on projects with Earl and Roc. Will those be coming this year?

Those are both coming this year. Now, I’ve made my bed.

[Laughs.] Some more to look forward to.

Definitely. This year’s going to be good. Also, a Larry June EP. I’m just trying to clear the runway for all these things, and lots and lots of vinyl releases that we’re doing. We’re redoing Covert Coup, and there’s a couple other things we got brewing. I’m looking to keep the year busy, and that’s the beauty of being independent. I know sometimes it looks like, “Damn, we’re doing a lot,” but that’s the freedom we have. Sometimes you’re on a label, and there’s a schedule, and you’ve got to wait for someone else. But for me, I try to keep things busy, so I’m always having something drop. Keep people fed.

When it’s something you want to do, it doesn’t feel so much like work, I guess.

I’m more depressed without work. If I don’t have shit lined up, that’s when I start getting worried. Lining things up is important for me, because when you’re your own boss, you can’t abuse the luxury. I can easily just fuck off and watch TV or fucking throw darts at the wall. No one’s going to fire me. Because of that, I’m like, “Don’t play around man. Set your shit up right, and keep your year busy.”

I could probably put a number [up on the wall] and go, “This is what we’re aiming for this year and let’s figure it out.” But it’s really a combination of that, as well as making sure my brand is always something dope. Obviously it’s not money, but as I get older and we’ve dialed in the dope part, I think people know we’re a brand you can trust. Now I want to find ways to expand and not worry so much about, “Oh, this isn’t going to be dope, or it’s about the art.” Of course it is. I think we’ve established that thus far. [Laughs.] That’s where I have fun coming up with different, cool ways to create things that have value, like the baseball cards with Bo.

That was a fire idea by the way.

The cards?

Yeah.

I was lucky, man. They got better than I thought. It really worked well, with the way that we limited them, and now they’re reselling like crazy online, which was really my goal. I could’ve made way more of them and got them to everyone, and then people are mad they missed it. But sometimes all money is not good. It just depends what you’re going for. I don’t want to burn out. I want to create something that lasts. You’ve got to restrain yourself sometimes, from a business perspective. It worked out well.

It’s always cool when you can share your other passions with your music. Just to kind of show more of who you are, and what you’re interested in.

With cards, I was doing that. I do a lot of different art. That was the series I was working on, and once we came up with the titles for Bo Jackson, it made sense. I can introduce my card art through this. That was a cool way to bring all the worlds together. I used to go buy cards, and go to Thrifty’s and get the 25 cent packs and hunt for those rookie cards or whatever. It’s similar to the hunt I do when I go record shopping. It speaks to the same excitement of getting something rare and finding it. That’s why I think it connected with that whole group of people who grew up that same way. Everyone’s like, “Oh perfect. Now you backed it up with some music that I like too. Perfect. These are all things that I love.”

“Shouts to Hit-Boy. This’ll be the only one I got over him. He’s been kicking my ass in every award competition. That’s my man, too. I love him.”

With everything being digital, it’s cool to be able to attach something physical that people will value. I feel like a lot of the newer generation hasn’t experienced that when it comes to consuming music. Everything is just available at the click of a button.

We’re not in the metaverse yet. It’s being built. I’m taking all my physical shit with me into the metaverse, too, just for the record. I’m working on that right now. My physical belongings will come with me into the metaverse.

You’ve got to hit up Elon about those arrangements.

You’ve got to figure this out, man. We need a cloud for physical stuff. We could keep all our belongings in a cloud somewhere, floating in outer space while we live in the metaverse. We’re going to figure it out.

[Laughs.] Is there anything that I didn’t ask that you want to express to the reader?

Shouts to Hit-Boy. This’ll be the only one I got over him. He’s been kicking my ass in every award competition. [Laughs.] That’s my man, too. I love him. I think he’s getting what he deserves. I think he really cracked the code personally, too, because he’d been dope for so long. I think him tapping in with Nas, and Benny, and Big Sean, is kind of similar to how we’ve all been doing, I think. I’m happy to see that, because sometimes you go down and go back up. I’m not saying he was [down]. He’s been the man. I’m just saying, he’s that guy, and he didn’t even have to do it through any system. He was kind of doubling back and linking with people that he fucked with, and that’s what we do.

Yeah. As a producer, sometimes you’ll have periods where you’re not in the forefront as much, and people will think you’re down or “fell off.” But you could just be going back to the drawing board, which you need sometimes, and it looks like that’s what he might have been doing. He’s putting out amazing work.

Yeah, and he cracked the code. I think personally, whatever he is on now, I love seeing it. [I love] having people out there that you respect, who are doing good, like sparring partners. “Man, he keeps me on my shit.” I definitely let him know, like, “Yo, you inspired me, and thank you.” I liked seeing him get what he was supposed to get, because I think it had to do with him not focusing on making hits for everybody, but locking in with people who he fucked with and making real music.

Shout to all of the producers, man. I just think of so many names and you say ”alive,” I can’t say I’m worthy to stand on the mountain and be like, “Yes. Yeah, yeah.”