On October 28th, 2017, Ice-T will step into a time machine.

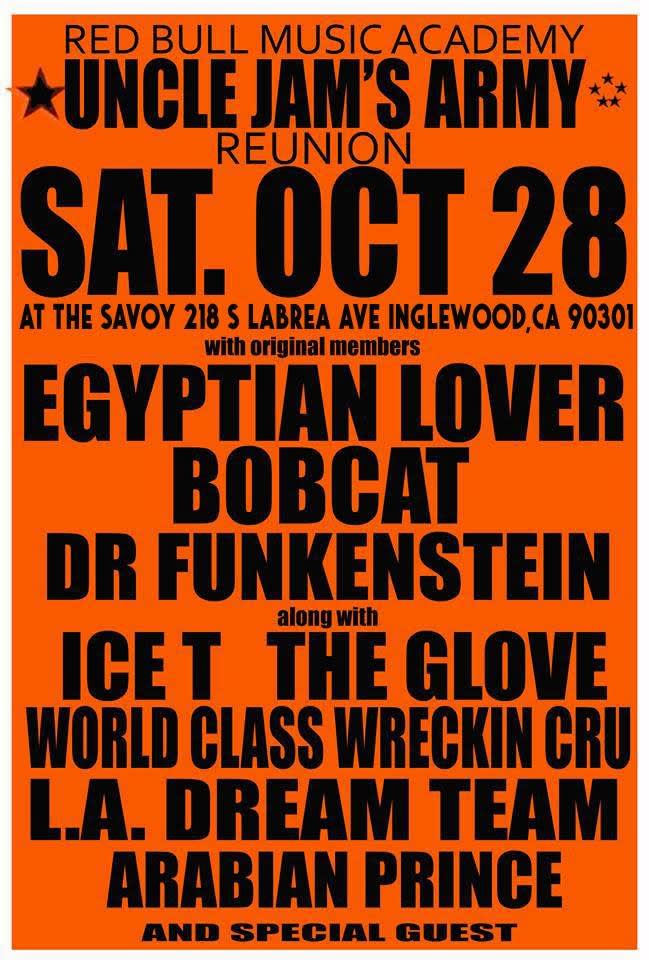

Don't worry—the rapper/actor won't be part of some weird Tank Girl sequel. Instead, he'll be traveling back to the very beginning of his music career in 1980s Los Angeles. As part of L.A.'s Red Bull Music Academy, Ice will be giving a lecture on his early days. And later that same night, fans will get a blast from the past when he reunites with members of the legendary DJ crew Uncle Jamm's Army (or Uncle Jam's Army—spellings differed) for a party on the former site of the influential venue Skateland USA.

Uncle Jam(m)'s Army was the DJ crew in L.A. during the early 1980s. Founded by Rodger Clayton in the mid-1970s, the crew had the top DJs of the time, some of whom would go on to shape the sound of hip-hop in the years immediately following the crew's heyday. Members included Egyptian Lover; DJ Bobcat and DJ Pooh, who would form the influential production collective the L.A. Posse (Bobcat was the DJ for LL Cool J, while Pooh went on to co-write Friday with Ice Cube, in addition to producing classic rap records and malt liquor jingles); Joe Cooley of Rodney-O & Joe Cooley fame; former N.W.A. affiliate Arabian Prince, and many more.

And of all the DJs, b-boys, and assorted hangers-on, there was one main guy Uncle Jamm's Army would let on the mic at their parties, some of which drew up to 5,000 kids: Ice-T.

So I called Ice to learn more about Uncle Jamm's Army, L.A. in the '80s, and what the hell to expect on Saturday. You can also check out the Red Bull Music & Culture documentary on Uncle Jamm's Army above.

(This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.)

There are two things with this event: your talk, and then the reunion party. So, to start with the lecture: what are you planning on talking about?

I kind of roll with the punches. I think usually when people around hip-hop wanna talk to me, they wanna know a lot of stuff about how it started, especially West Coast hip-hop. I was there at the birth of it, and gangsta rap. Kind of like my journey—where I started in the streets of South Central and dealing with all that stuff. And now, how the fuck did I end up being on television playing a cop for 19 years? [Laughs.] So there's a lot to talk about.

There definitely is! When did you first become aware of UncleJamm's Army?

Well, really since their birth. Actually, what Uncle Jamm's Army was, was a bunch of club promoters that realized there was a market in the ages 16 to 20—kids that couldn't get into clubs yet. And they basically put together the earliest form of a techno-type rave, but they did it on a massive scale. So when you were in that age bracket, and even if you were 25 or something, this was where you would go that it wasn't a club yet. And they realized there was a massive audience for that, and of course everybody would know when they were throwing parties. They had big promotions on the radio, and I think we just went to investigate them at some of their smaller events.

How did you first get involved as a participant, as opposed to just someone going to the parties?

When they first started, I hadn't even started to rap yet, 'cause they were pre-me rapping. At that time, we used to go there, but we was criminals. So I would show up in there—you know, there'd be like 40 of us. My crew, guys and girls, we used to all wear Fila and go up in there as some place to go. So Rodger and them were aware of us. They were like, "OK, Ice-T and these cats, these are some interesting individuals." 'Cause we were part gangbangers, part players—it was different.

And then, as I started to try to rap, they were the first people that let me on the stage, 'cause they were like, "Well, he's got a lot of street pull. Let's see, can he rap?" And you know, I sucked right out the gate, but I was the only person they would ever let rap.

I heard they almost never played rap records at their parties.

Well, there was no rap records, you know? There was none; at that time, we were rockin' off of groups like Egyptian Lover. I call it "aerobic music." Lots of breathing and shit, you know? [Laughs.] A lot of, "ahh," "uhh," "ahh," you know? This is pre-rap. Run-DMC and them hadn't hit yet.

I read you used to dance, in addition to rapping.

I used to try to breakdance sometimes. Once you get connected to hip-hop, you try to do every part of it. You get in. That's the cool thing about hip-hop—hip-hop is a culture that you like and it's tangible. It's something that, with a little practice, you can do. So first, you're trying to dance, you're trying to lock, you touch the turntables, you kinda get in where you fit in.

I tried to be a DJ, but then I was getting more attention rapping, and it was easier, 'cause I didn't have to carry speakers around. So I would just show up in places and start to rap and stuff. I really didn't take rap serious until Run-DMC broke, because no one had made any money doing it, and I was on the streets hustlin'. We were getting money, so it was just something to do to get girls. It was something to do as a pastime. Never thought it could actually be an occupation or a job. It was just fun to do.

I sucked right out the gate, but I was the only person they would ever let rap.

Uncle Jamm's Army had a pretty famous show at the L.A. Sports Arena that had around 5,000 people. Were you there that night?

Yeah. They had more than one [show at that venue]. They did the L.A. Sports Arena, they played the big venues. But the big one you're talking about, yeah. It was phat. You've got a whole dance floor full of people dancing. Back then they did the Freak, everybody's freakin' on each other. And you had no acts. There was no headliners; it was just, like I called it a rave. Nowadays, you do raves, and it's all DJs. There's no rappers, there's no singers; it's just DJs. So you had Bobcat, who's one of the DJs. You had Arabian Prince, of course, you had Egyptian Lover. You had Battlecat. You know, you had Rodger and Gid [Arthur "Gid" Martin]. And they basically were the show.

Out of that crew you just mentioned, and other people like DJ Pooh who were involved, you had folks who would lead the next half decade or so of hip-hop. Why do you think that kind of talent and that kind of innovation came out of Uncle Jamm's Army?

Well, hip-hop is a youth-based culture. When hip-hop really hit New York, all of us were young. So, whether it was Dr. Dre, who was running the World Class Wreckin' Cru, and they were doing the same type of parties [as Uncle Jamm's Army] in Compton and stuff. You had another group called Bay 5. All of us were just youngsters involved in music at the time. So it was natural that would progress as New York hip-hop started to merge with West Coast techno. You'd come out with groups like myself, N.W.A., Coolio, and all these different people.

What was Rodger like back then?

Rodger was a very business-minded guy. He was a hustler. He was the West Coast Puffy, you know? He could take anything and make it into something. If he liked you, you could talk to him, but other than that, most people couldn't even talk to Rodger, you know?

He was the man. They were makin' truck loads of money, him and Gid, his boy. He had a lot of cats: Rodney O; Russ Parr, who came out with Bobby Jimmy and the Critters, he kind of connected to them. They had the biggest situation, outside of a nightclub. And it was bigger than any of the nightclubs.

What role did Don McMillan and Macola Records play in the scene at that time?

Well, they were the way we made records. They had a pressing plant on Santa Monica Boulevard. You could just walk in there with a tape, and they'd press your wax, just like that. Fuck a record deal, you'd just go in there and make wax. So that night, you could spin it. And if McMillan thought you had something, he would advance you money on a record.

Now, if you walked in there and he gave you $10,000, he's gonna sell records out the back. You ain't gonna know how many records he's fuckin' sold. So he would rip us off. But that's where 2 Live Crew started, I started, Tone-Lōc, Delicious Vinyl—all that stuff started there. Of course, Dre, Eazy—all of us were gettin' our records pressed at this pressing plant, Macola Records, right there in Santa Monica.

What place can you do that; can you walk in the front door with a cassette tape, and walk out with vinyl? You know, that was amazing. No contracts, nothing. So we were able, by the time we got to the majors, to say that we had moved 50,000 records out of our trunk, and we weren't lying.

I have a question about your very first record, "The Coldest Rap." How did you get members of The Time to do the music for it?

I was at a beauty salon called Good Threads, in the hood, gettin' my hair done. That's when I had a perm. I used to get my hair done twice a week. And I used to rhyme to the women there, just bullshittin', just talkin' shit. And this guy named Willy Strong, who ran V.I.P. Records at the time, and another guy named Cletus Anderson, they were a record store. He overheard me rappin', and he said, "You wanna put that on wax?" And it was like "Sucker M.C.'s," where Run said, "Larry put me inside the Cadillac/The chauffeur drove off and he never came back," you know?

I went to the studio, and I had never made a record. He had this record with The Time on it, but there was some people singing. He owned it. Now, how he owned the track, I don't know. But Willy Strong and them owned the track, so they just wiped the vocals off and gave me the instrumental. And I just rapped all the rhymes I had in my head at the time. No preparation, just the shit I had in my mind, and I made a little hook: "I'm a player, that's all I know/On a summer day, I play in the snow/From the womb to the tomb, I run my game/'Cause I'm cold as ice and I show no shame." I made that up on spot, and then I would just say my freestyle bullshit in the hook, and that was it. And that was "The Coldest Rap." That was the first song. And I made, like... I made about $400. [Laughs.]

Well, I'm glad you moved on from those days! What is it like for you to see the electro scene of the '80s start to be taken more seriously and archived? You see it in movies, you see it in books, you see events like this where people are talking about it. What is that like as someone who was there when it happened?

It's just history, you know? People always refer to West Coast rap and at least West Coast people are being honest about it and saying, "Yeah, it was a very techno-based scene." I mean, it wasn't the same boom-bap as New York. It was different.

My first big record probably would be "Reckless," which I did with [producer Chris "The Glove" Taylor]. And that's a techno record, you know? He’s techno.

And it's funny, 'cause Eminem said that's the first rap record he ever heard. I was intrigued by New York rap, so I wanted to rhyme more like New York rappers, with more bars and verses and hooks. And now, you've got rappers like The Game. You listen to him rap, you can't tell he's from L.A. He raps like a New York rapper. So, the emergence of the sound, it just happened like that. Dre and them had Wrecking Cru, they did songs like "Surgery." That's the sound of L.A. at that time.

Lastly, what can people expect to happen at the reunion party on Saturday?

I have no fuckin' idea. I talked to Glove and I asked him, does he have an instrumental of "Reckless"? And he said yeah, 'cause I don't like rappin' over vocals. Then he said, "And I was thinkin' we'll just do some freestyle shit," like me and him used to do. I'm like, "Well, that'll be interesting."

I'm just goin' for support. You know, Egyptian Lover called me and asked me, would I go and be part of this? You know, he's a G. And when you get that G call, you show up. That's how it happened. I'm excited about it. I'm glad I was able to make it happen.