College, for many, is the time of new possibilities. During my first and only year of college, in the serenity of a small Pennsylvania town, two rap legends gave me clarity about how boundless, subversive, and versatile the hip-hop world is. I can’t say I retain much from those general ed courses, which is my own fault, but I learned to engage hip-hop in a totally different way thanks to MF DOOM and Sean Price, two rebels who shirked industry norms and helped many discover new hip-hop scenes that existed outside the mainstream bubble.

Like most people growing up in the aughts, my perception of hip-hop was defined by BET, MTV, and the radio. It was a nice crash course, but in hindsight, it was limited. It wasn’t until I started to delve into the mixtape scene that I found artists who existed outside of the 106 & Park countdown. But even then, my feeling was that rappers like Papoose and Saigon sought to eventually ascend into that mainstream sphere themselves.

I knew that being hip to the “next up” artist wasn’t the same thing as being up on the scenes that existed outside mainstream visibility and were supposedly “too smart” for BET, like Little Brother. Mainstream acts like N.E.R.D, Kanye West, and Lupe Fiasco were instrumental in piquing my interest in left-of-center sounds, but I hadn’t yet engaged with “the underground.” That opportunity finally came in the summer leading into college, with lots of free time and a budding curiosity.

The first person I tapped into was Sean Price and Monkey Barz. I had previously heard him on the GTA III soundtrack, but I didn’t know much about him. It only took my first listen to notice that he sidestepped the norm. Most artists in my admittedly limited rap consciousness at the time were coveting riches, and fakin’ it til they made it, so imagine my surprise when my new favorite MC became “the brokest rapper you know,” Sean Price. Not only did he make no bones about not having the trappings of wealth that rappers were “supposed” to have, he made his brokeness a central theme of his sound. Sean P cracked a code for my rap listening experience. It was an extended comedy bit over song, like an Al Bundy who once scored on four stickups in a night instead of touchdowns. I had experienced rappers who were crotchety and merely came off miserable with their industry experience, but P captured that same resentment and made it hilarious.

In the solitude of my dorm room, secluding myself from the challenge of trying to actually meet new people, I was invested in finding more magnetic MCs that BET had hidden from me. That same summer of ‘06, I was listening to Ghostface Killah’s Fishscale, a beloved album that had several standout beats produced by MF DOOM. “9 Milli Bros” was a fitting banger for the Wu reunion and “Clipse Of Doom” was a noxious sample fit for battle rhymes, but “Underwater” was the one for me. It wasn’t just Ghost charismatically exploring a nautical netherworld; it was the way DOOM’s beguiling soundscape actually sounded like one was underwater, years before OVO changed our understanding of that phrase.

Around the same time, I came across a massive Wu-Tang blend on Limewire, and a friend told me they were actually rapping over the beat for DOOM’s “Rapp Snitch Knishes.” I found it, and immediately died laughing. How could one not be amused by, “‘Do you see the perpetrator?’ ‘Yeah, I'm right here’/Fuck around, get the whole label sent up for years.”

DOOM was a social phenomenon in the purest sense of the phrase, like the lone game of telephone that carried the same message throughout: Just remember ALL CAPS when you spell the man name.

Like Sean P, DOOM had come for the absurdity of one of rap’s sacred cows: letting people know how you got it in the streets. At my age, I figured that’s just how it was, with artists trying to outreal each other by marketing themselves as true-to-life as possible. I’m sure their labels had no problem with the circumstance; they’d face none of the consequences. Rappers deserve their artistic license to say what they want without police departments and politicians trying to nail them, but damn, there are stories of some artists making it easier than others. “Rapp Snitch Knishes” is an unforgettable song that struck at that. As an avid fan of satire, I was hooked.

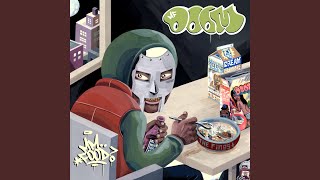

It wasn’t just the concept of “Rapp Snitch Knishes,” though. It was DOOM’s mic presence. His verse made me check out the rest of MM..FOOD, and I was immediately hooked. I hadn’t been exposed to many actual concept albums yet, so it shook me up to hear someone use random foods as the setoff for Adult Swim-worthy narratives. He rhymed like a seer from a parallel universe, back with assonant parables in tow. You might not get the moral of the story, but you’d be entranced as he went from line to line, occasionally tumbling through his rhyme scheme like a downhill runner trying to stay standing.

Then I explored his Madvillainy project with Madlib. It was a meeting of two masterful minds that resulted in a one-of-a-kind listening experience. Some albums are “post” and “pre” moments. It’s hard to play Madvillainy and not have felt like you just had a transformative listening experience. It was like a jazzy, soulful fever dream, as it crunched together short, one-verse songs before it was the norm.

It didn’t take much for me to realize this was what freedom sounded like. This is what’s possible without a label exec putting a metric-based ceiling on genius. I knew hip-hop was storytelling, but I hadn’t heard someone have that much freedom with it beforehand. That’s not a statement on the history of rap, but my personal listening experience. DOOM embodied the supervillain, and like P, he cloaked himself inside his own sonic universe. It was unabashedly nerdy, but also so vast that you could delve in and marvel alongside someone else, who you inevitably put on to his music. You didn’t need a million other people to be in on this.

Perhaps that immersiveness was a credit to DOOM being a rapper and producer who controlled the bounds of the experience. His Special Herbs instrumental series was an entirely different experience for me. His prolific nature and versatility was astounding, and I was intrigued that he wasn’t scared of just looping certain samples, knowing that his rhymes (or those of his rap peers) would keep you enthralled.

Listening to his beats opened up a whole new world of artists to explore. Sometimes I’ll play the Special Herbsbox set on Spotify, clicking on a random song which invariably triggers an old memory. Those moments take me back to nights in ‘06, listening to his brilliance in the wee hours of the morning while I ponder my future.

Ultimately, things led me here, writing about music for a living. Who knows how much appreciation for music I’d have if I didn’t push beyond the mainstream and explore the scenes once deemed “the underground.” If anything, they were the painted sky over the steely skyscrapers of mainstream rap, with their sterile polish and recycled machinations. Try as they may to convince us that industry might automatically means merit, few mainstream acts reached the heights that artists like DOOM and Sean Price did.

As I’m learning in the time since DOOM’s tragic death, millions of others felt the same way. There’s confusion about what “underground rap” even means in 2021, but DOOM’s career harkens to a time when there were clear lines between mainstream rap and other scenes. Major labels had connections with TV, radio, and the biggest press outlets, and an artist generally had to go through them to reach the masses. DOOM was one of the few exceptions who grew his fanbase organically.

Most learned about him through word of mouth, whether it was small internet message board communities, friends, or indie radio stations (with no motivation beyond playing the best rap music). I learned his name from friends, who I’m pretty sure learned about him from friends, and so on. He was a social phenomenon in the purest sense of the phrase, like the lone game of telephone that carried the same message throughout: Just remember ALL CAPS when you spell the man name.

He prepared himself for that dynamic as a literal mysterious masked man. While so many MCs sought relatability with fans via their life story, DOOM went the other way, pulling us in with intrigue about just who he was. Being a DOOM fan was deeper than enjoying the music. The average rap fan could tell you a random fact about where their fave went to school, or what their parents did. I remember so many people my age, unaware of his previous career exploits as Zev Love X, who just wanted to know what DOOM looked like. Even today, the internet doesn’t trace the timeline of Daniel Dumile’s career besides occasional interviews and features—mostly from the DOOM days. There was an entire mythos to tap into with DOOM, which so many kids like me were eager to explore.

He carried that mystique into his art, cultivating an overarching narrative of a rap supervillain who was observing lesser MCs making the same old song. Nothing else anywhere sounded like “Accordion” or “One Beer” or “Figaro.” He rhymed about his supremacy with a jest that belied Jay-Z’s passionate cases for GOAThood. On “Doomsday,” he referenced his jail stint without the chest-thumping ego the average artist would employ. DOOM’s approach was just different.

For a kid who was used to being presented with a limited amount of rap archetypes, DOOM was exciting. From my limited scope, it felt like so much of the mainstream rap that was presented on TV and radio were rappers who rhymed about being in the streets, and then the occasional rappers they co-signed (an Eminem or Kanye) who sidestepped rapping about guns and drugs. And again, there’s nothing wrong with that content, but balance is important. DOOM defied all that. He rapped about whatever he wanted in an oddball package. He was too inaccessible to even be worried about labels like “nerdy” or “weird.” After all, there are plenty of Black people who are just that. We deserved some representation, too.

It’s fitting that Odd Future, a collective that represented the same thing for another generation of kids, were devout fans. They helped introduce DOOM to an entire generation of teens in the 2010s. But his impact didn’t just reach the artists who so obviously carry on his torch. Playboi Carti and Aminé are two artists who shouted him out in the days after his death. Even if they don’t sound like him, DOOM helped give them the freedom to explore left-of-center sounds. Carti’s rebellious, paradigm-pushing presence is in the lineage of DOOM.

There are so many incredible acts that shaped my experience in the aughts, but it’s mainly about DOOM and P for me. Both of them actively shunned the majors, and thankfully so. They had the free rein to create engaging extensions of themselves that mere marketing couldn’t possibly envision. Their insularity was more sophisticated than, “I’m underground, fuck the mainstream.” That was implied, but they struck at those sentiments using their wit, humor, maverick lyrical approaches.

These guys didn’t need to be sold; the brilliance sold itself.