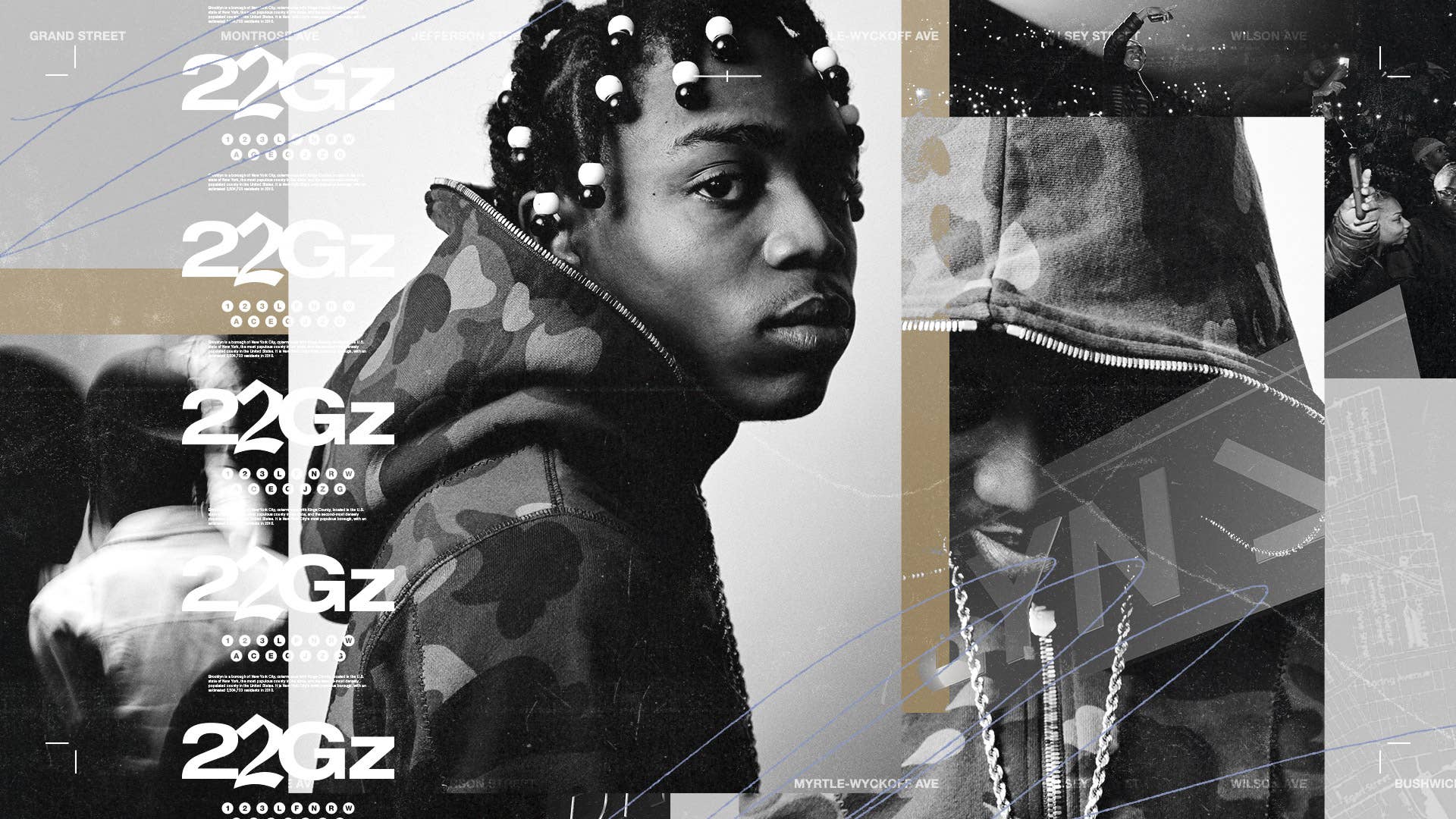

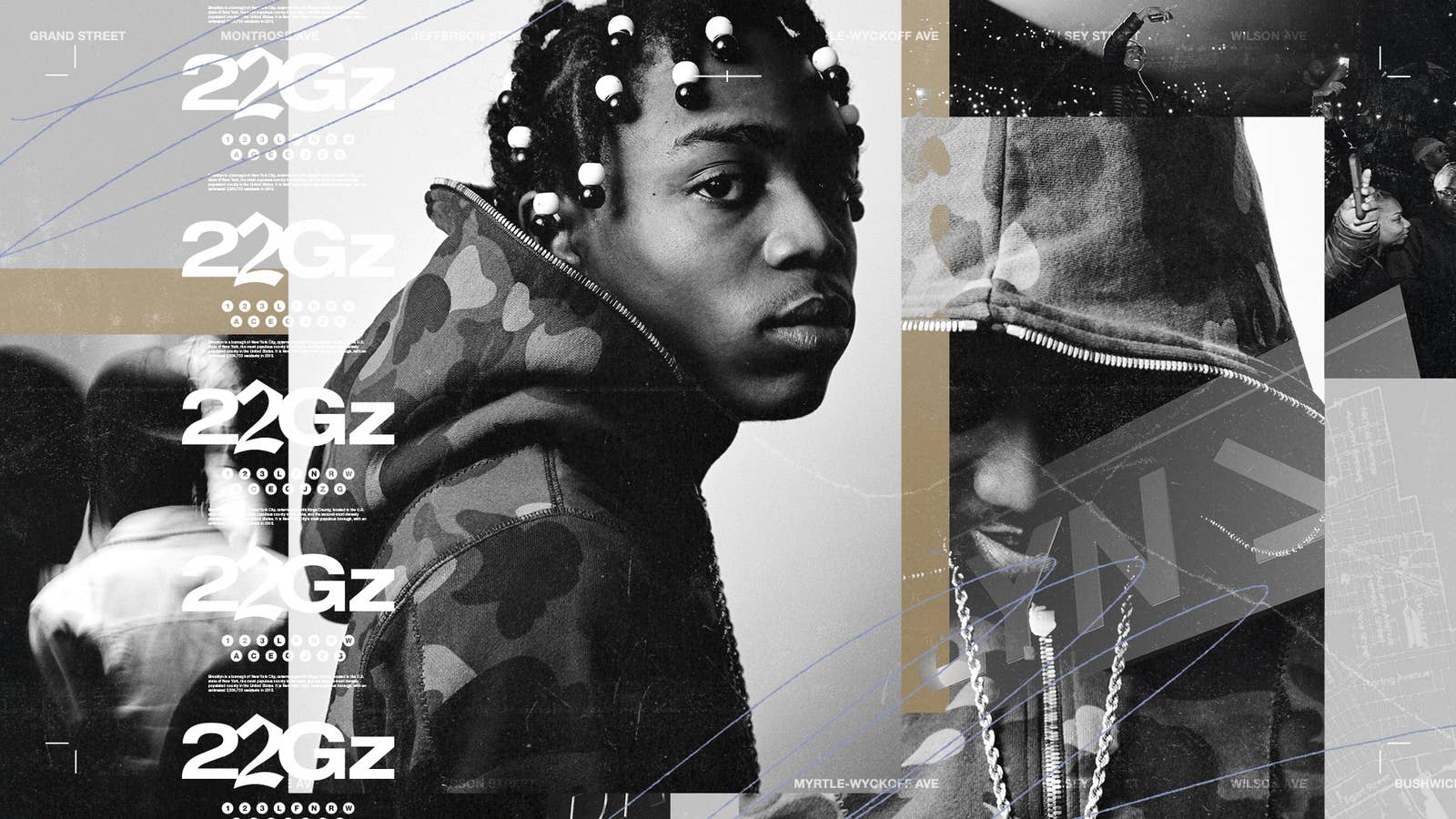

22Gz can’t stop smiling.It’s a vast and cheesy grin, and if you look closely enough, one corner of his mouth stretches a little longer than the other. It’s the kind of expression you’d expect to catch on the face of a buzzing young artist who is just now growing accustomed to his budding celebrity for the first time. Or, depending on the angle, it could be perceived as the smirk of a villain whose plot has not yet been revealed. On this overcast Thursday afternoon in early February, 22Gz’s confident mug fits both descriptions.

A rainy week in New York City has confined the rapper to an apartment in Brooklyn’s Flatbush neighborhood. It’s a cozy multi-bedroom space that belongs to his producer, TeddyDaDon, adorned with family portraits and furniture only a mother would purchase. In a bedroom tucked around the corner from the front door, 22Gz balances on the side of a bench, carefully rolling a blunt. He’s deep into a passionate discussion with TeddyDaDon and his nephew about scamming. Specifically, they’re talking about using fake dollar bills to score ounces of marijuana. They’re careful not to implicate themselves in these amateur heists, but their deep knowledge of the topic betrays their innocence.

“Don’t worry, we’re not doing drug transactions in here,” 22Gz says, smirking.

Moments later, posing for photos for this story, 22Gz shields his face with a BAPE hoodie as he cracks up between takes, poking fun at the sheer awkwardness of the moment. His smile is even bigger and more mischievous than before.

“I’m happy, because I know what the worst could be,” he says. “Shit can always go left. So I thank God and I’m happy. I work hard to make sure shit will never turn left again.”

22Gz is too focused on building his legacy to dwell on hardships. Since releasing his breakout single, “Suburban,” in 2016, he’s become one of Brooklyn’s most talked-about young rappers. The track also earned him recognition as a trailblazer of Brooklyn drill music, although he says he doesn’t always get the credit he deserves as a pioneer. He’s working every day to change that.

Born Jeffrey Alexander, 22Gz had his fair share of misfortunes. His father died before he was born, then his older brother got 16 years in prison. And that’s just the beginning of the challenges he’s been faced with.

“I’ve been evicted on my birthday before, and been in jail for fucking murder, extradition,” he recalls, calling the rainstorm of adversity the reason he can’t stop smiling now that his luck has turned.

Those murder and extradition charges made national headlines when, in May 2017, the rapper was arrested and charged with second-degree murder with a deadly weapon and second-degree attempted murder with a deadly weapon. Alexander was reportedly riding in a white BMW with three other men in Miami, Florida, when the driver of the vehicle attempted to parallel park in a spot that was too small, hitting a gold Buick. Ladarian Tyrell Phillips and Edward Ellis, the Buick’s owner, witnessed the accident from across the street and confronted everyone in the BMW. After a verbal argument, the driver fired a gun, shooting both Phillips and Ellis. Phillips was killed; Ellis survived.

Following the shooting, the BMW raced off, leading police on a high-speed chase. Miami Beach police officers opened fire, killing the driver of the BMW. At the time, Ellis alleged that “the front passenger” (22Gz) was the shooter. Alexander spent five months in prison before the State Attorney’s Office determined the driver of the BMW was the shooter.

This wasn’t his first run-in with the law. In 2014, 22Gz was charged with conspiracy to commit murder, according to Brooklyn Supreme Court records. He and three affiliates, who were believed to be members of the Flatbush gang Young Savages, were accused of plotting to kill members of a rival gang known as Only the Fields. He was never convicted of those charges, but the experience of narrowly escaping hard prison time inspired him to change his ways.

“I started most of this stuff from scratch: the flows, the bars, even the swag is mine.”

“There was a lot going through my mind,” he remembers. “I had two cases open. I got extradited on the plane. I beat the murder already, but I had an open case in New York for conspiracy or whatever. That really showed me I was out here playing in these streets, just doing anything. Waking up, bugging out. That made me really tighten down on myself.”

22Gz’s friends and family also encouraged him to shape up and direct his energy to music. “I had a wanted picture for a shooting, and I was on the run at my bro’s crib,” he says. “I wasn’t really paying attention to it too much, but they was just telling me, ‘I ain’t gon’ front, you got bars. I think you should really take this shit serious. Go to a studio and drop some for the homies.’”

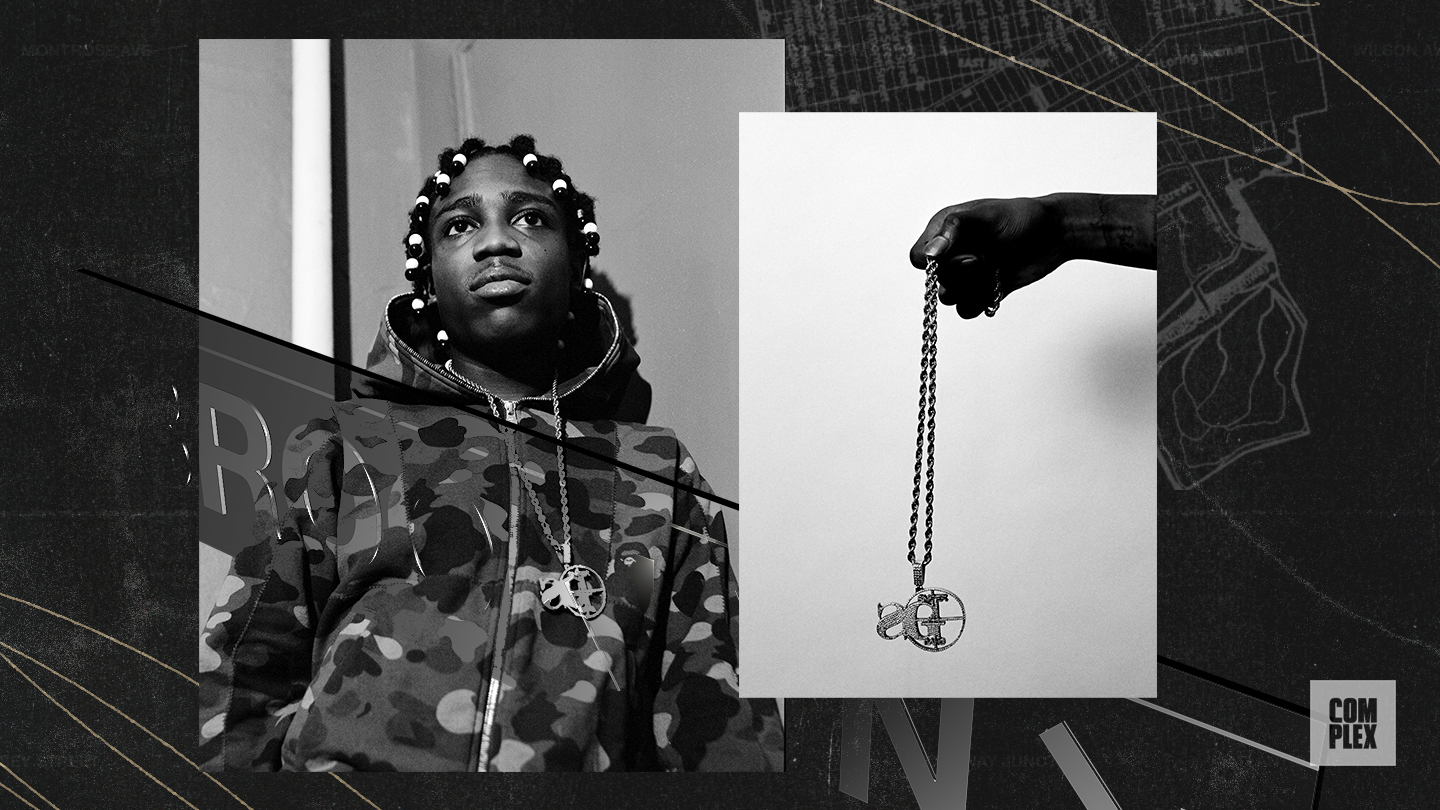

In 2016, he released his first song, “Blicky,” under the name 22Gz, which combines aspects of his childhood and street life. The “22” (pronounced “Tutu”) refers to 2 Lane Avenue, the New Orleans address where his parents discovered they were pregnant with him. Then he “added the Gz to it because of my affiliations.” On “Blicky,” 22 says he was just trying things out. But “Suburban,” his second release, transformed him from a street artist to full-blown rapper. The breakout hit is widely considered the first major record to lay out a blueprint of what the Brooklyn drill sound would become—full of raw, unfiltered intensity and bass-heavy production from AXL Beats. The accompanying video and overall style were reminiscent of the work of early 2010s rappers in Chicago’s own drill scene, but 22Gz’s take on it was fresh in Brooklyn when “Suburban” dropped. It generated hype immediately.

“That’s what gave me the push. I asked for 100,000 [views on YouTube], and now I got a million,” he says. “So it’s only right that I keep going.”

22Gz brought an authenticity and aggression that was unrivaled in Brooklyn at the time. He packed each verse with vivid details of his street lifestyle, like, “It’s a man down when we lurking/Pull up in all black we purging/Pull up in all black suburbans/If he ain’t dead, we reversing” from “Suburban.” Later, on 2018’s “Spin the Block” he spewed more deadly lines as warnings for anyone trying to diss his crew: “Headshot, face shot, if them rakes is dropped/ABS and PIX11, yellow tape the block.” As 22Gz would argue, you can say what you want when you’ve really lived that life.

“I’m not going to say a lot of the shit I did, but a lot of this shit is real,” he says. “I ain’t fucking capping, I’m not playing. The rest of the drill rappers, they haven’t really been through what I’ve been through. I’ve been through real shit where all life’s trauma, and I’m still here.”

These raw, real-life experiences are what caught the attention of Kodak Black, who signed 22Gz to his Sniper Gang label in 2018. “You can see that we’ve been through the same shit,” the Brooklyn rapper says, noting that he beat his murder case in Kodak’s home state. “I can relate to him.”

As 22Gz was catching fire, so was the rest of the Brooklyn drill movement. In 2017, fellow Flatbush rapper Sheff G responded to “Suburban” with “No Suburban,” a song that built on the momentum 22Gz ignited. Later, hits like Pop Smoke’s “Welcome to the Party” and Fivio Foreign’s “Big Drip” helped bring the Brooklyn scene to the national stage. But, according to 22Gz, none of this would have been possible if it weren’t for him. Thus, he declares himself the “General” or the “drill pioneer” of the subgenre.

“I started most of this stuff from scratch: the flows, the bars, even the swag is mine,” he says. “I’m not going to say I’m the first person to ever [do this]. Don’t get me wrong, there’s other artists. You had GS9 and Bam Bino. But ‘Suburban’ was for the younger crowd, my crowd. I started ‘Brooklyn drill.’ There was no such thing as ‘Brooklyn drill’ when the other songs was out.”

It’s a bold statement, but 22Gz was the first to multiple trends that validate his argument. We’ll start with his adoption of AXL Beats’ production. The U.K. producer is the not-so-secret weapon of the drill movement, earning credits with everyone from Sheff G to Fivio Foreign to Pop Smoke to Travis Scott and Drake. 22 says he was the first to “borrow” AXL’s beats after unearthing them on YouTube. After he ripped the beat for “Suburban” without permission, he and AXL developed a real working relationship, which was later duplicated by every other major player in the scene. “He was like, ‘Bro, your song is doing good,’” 22Gz recalls. “I said, ‘All right, send me the beat for real.’ He sent me the real beat, and it was lit.”

Another trend he started is the Blixky Twirl, a dance where “one leg crosses the others and you get low with a spin twirl.” As he puts it, “Everybody added they’re own moves and their own twists to it but never looked back to say this guy started it. I've seen Offset Blixky Twirl. It's crazy, I've seen everybody twirl, and it’s not like they tag me or anything. I want to know, do they know that’s my dance, or they just don’t see anything? I’m not saying Offset or 6ix9ine, because [6ix9ine] knew that was my dance and he stole it. But that's what I see. You got the whole NBA doing it. I’ve seen [Russell] Westbrook doing it.

“Hopefully I can make an anthem, so when they see me doing the dance, they know it’s mine,” he adds, brushing it off. “But to start something from scratch, you want your credit.”

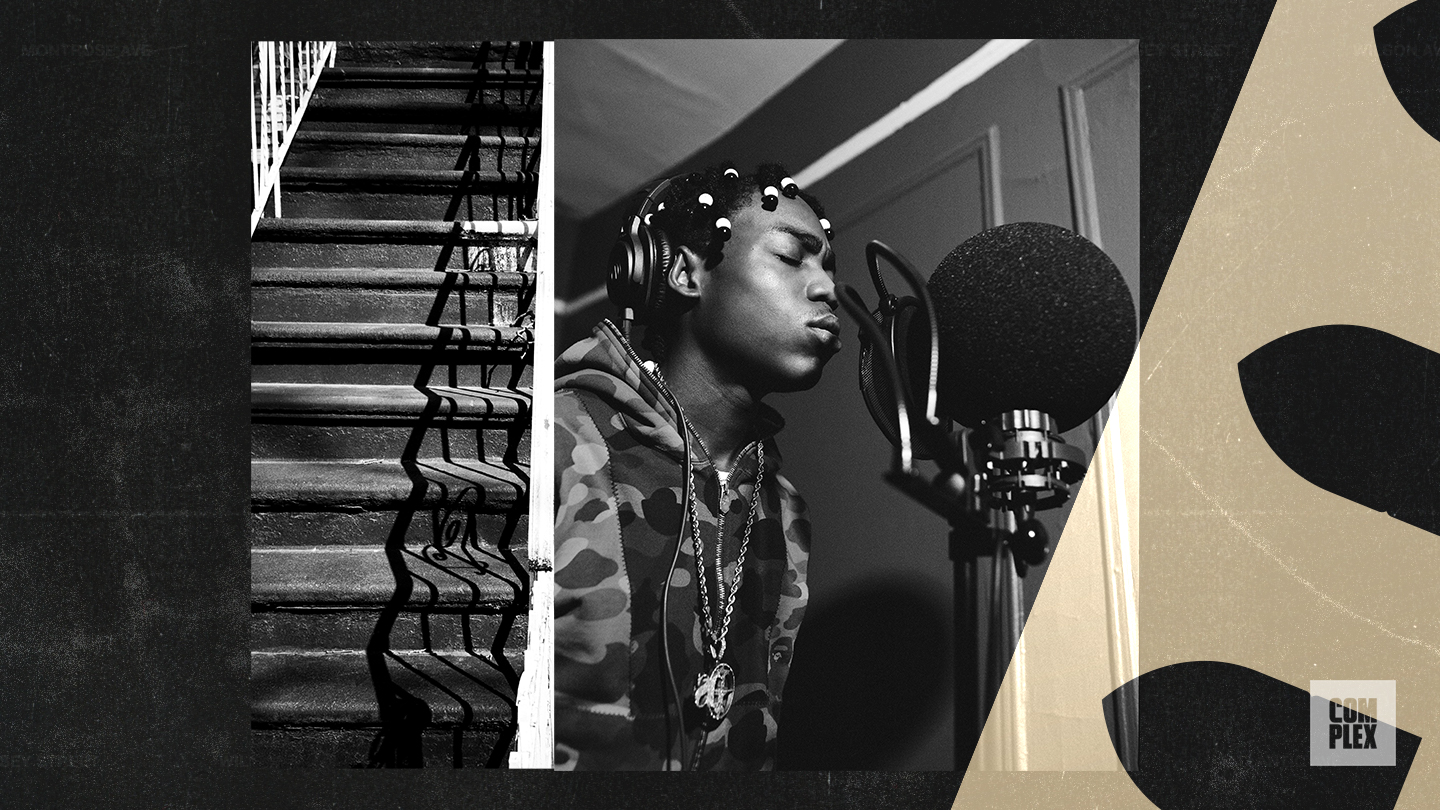

Back in the Flatbush apartment,22Gz is working on a future anthem. His smile has been replaced with a scowl, and he’s rehearsing a few bars aloud, making sure each line lands in the right pocket, hitting with the same vicious energy as it did in his head.

He punches in. “Is you ready for war?”

He recites his next line with the tenacity that Brooklyn drill rappers have become known for. “If we catch ’em lackin, we sending ’em straight to the lot.” The verse takes all of 15 minutes to finish, complete with ad-libs, faux gun shots, yahs, and his Blixky chant. 22 admits that some songs take longer than others, especially when he’s recording a full record from scratch. But what’s more impressive than his recording time is the way he’s able to flip from one mood to the next in an instant before recording. He insists this is the nature of the scene. “This is Brooklyn drill. We have to be aggressive,” he explains. “I have to deliver them bars.”

22Gz says he’s always ready for war because of what he refers to as “the competition.” There’s a growing perception in the neighborhood, and beyond, that 22Gz is the antagonist of Brooklyn drill—the villain. But he claims the entire city is “ganging up” on him. “If you go through most of the NYC Brooklyn drill artists, their hit songs are dissing me—almost all of them,” he insists. “If you go to my hit song, it’s my hit song. You get what I’m saying? It’s weird. It’s like they dissed me to get fame.”

He shakes his head. “The whole Brooklyn, they see it. Everybody should see it now. There is a lot of alliances against me, trying to beef with me. I’m not talking about in the streets. I’m talking music.”

He doesn’t share any specific names, but it doesn’t take much searching on social media to catch rumors of beefs between him and countless rappers in the Brooklyn drill community.

While gossip fuels beef between him and other artists, 22Gz attempts to distance himself—sort of. “I don’t even know some of the guys, period, not from a hole in the wall,” he says. “They all just try to gang up and beef with me, but they don’t know me. And we could check. They ain’t on my type of tip, and I ain’t even on that tip no more.”

“The rest of the drill rappers, they haven’t really been through what I’ve been through.”

One day after Pop Smoke’s murder on February 20, he wrote, “All beef aside, I feel sorry for boy. This type of stuff is the reason I move with who I move with and move the way we move.” 22Gz declined to comment further on Pop Smoke upon a follow-up request.

He becomes visibly agitated while discussing conflict within Brooklyn, but he insists he’s unbothered. “To me, it don’t really matter, but I hope it stops, because I don’t want to hurt nobody, and I don’t want to see nobody on my team hurt,” he says. “Everybody just stay out my way, I stay out yours, and we good.”

22Gz clarifies that he isn’t “ducking no action,” though. He just has larger concerns right now. Besides his issues with fellow artists, he also has an NYPD problem that’s been affecting his pockets. In October 2019, 22Gz, along with four other New York rappers (Pop Smoke, Sheff G, Casanova, and Don Q), were removed from Rolling Loud New York’s lineup at the instruction of the NYPD. The police department argued, “If these individuals are allowed to perform, there will be a higher risk of violence.” 22Gz’s name was at the top of the list, which he suggests was deliberate.

22Gz says he has been banned from performing in his home city for the past year. “If they see me post a flyer, they’ll call the venue,” he claims. “They’ll say, ‘If he performs here, we’re going to harass everybody at the venue.’”

This extends to non-music events, too. 22Gz recalls an incident in which the NYPD’s 71 Precinct attempted to shut down his appearance at a Thanksgiving turkey drive inside a local school. “They went into the school and told them, don’t let me give out these turkeys because I’m a priority,” he says. “We still did it anyway, and everything went good.”

22 insists he doesn’t know where the negativity—the competition, beefs, lack of credit, hounding from the NYPD—comes from, but he feels like it could be a combination of “the gang culture or my gang affiliations or assumptions or rumors.”

“There is nothing I can do to fight against it,” he says. Being barred from performing in New York City does bother him, though. “I always wanted to perform in the middle of my neighborhood, in my city, and have it crazy lit,” he says. “I'm trying to make it out the hood. I have no open cases, and I have no felonies on my record. There is no reason why I shouldn't be able to perform.”

For now, 22Gz is intent on focusing on music. “I can’t call myself the General and not have music to back it up,” he explains. Kodak Black gave him a similar token of advice when he signed: “If you ain’t got no music, you ain’t no rapper. You got to have music in the stash. You must keep working.”

22Gz has been hard at work on two projects—a full-length album as well as a mixtape, Growth & Development, which dropped on April 10. The 13-track tape, produced entirely by U.K. beatmaker Ghosty, includes guest appearances from Kodak Black and Jackboy. As 22Gz would put it, he’s delivering “straight bars” over haunting drill beats throughout the project. Growth & Development showcases what 22Gz does best—brutally honest lyricism, flurries of addictive ad-libs, and an overall charismatic presence—but he hints that the drill sound isn’t all he has to offer. His follow-up LP could introduce new flavors to his style.

“I’ll try rock because that’s closest to drill music,” he says, before adding pop and R&B to the list of genres he’ll experiment with. As for collaborators, he’s “trying to get all the features I can get,” including A-listers like Drake, Migos, 50 Cent, DaBaby, and Lil Baby.

As the Brooklyn drill sound, which 22Gz is quick to remind you he pioneered, is expected to continue breaking into the mainstream, the young rapper is ready to capitalize. In the next five years, he hopes to receive RIAA-certified plaques, hit the Billboard charts, and sell out tours.

At the same time, the growing trend of mainstream artists and outsiders stepping into the Brooklyn drill scene is not lost on him. “That’s cool,” he says, “but save some space for the real niggas.” 22Gz flashes his toothy smile again as he settles back into his seat, admiring the movement he helped start. “You don’t want to have a bunch of crazy-ass killers in the streets, but you can’t just forget about all the real niggas who are really going through that shit.”

See below for the rest of the stories in our Brooklyn drill series:

We also put together a playlist of essential Brooklyn drill songs, which you can follow on Spotify.