What is it like to create the raw sounds that producers and musicians use to make songs?

For William “Sound Oracle” Tyler, it’s like making the art that Nick from Family Ties would construct from garbage. For Raymond “!llmind” Ibanga, it’s like cooking. For Robert “G Koop” Mandell, it’s like creating (and then immediately destroying) an elaborate sand mandala. To these elite music makers, the metaphor for describing the art of sound design may differ, but the creativity and dedication needed to stand out in this essential but little-understood corner of the hip-hop universe remains consistent.

Given how producer-centric hip-hop has become in recent years, most fans understand that a producer is the person who makes beats that rappers spit on top of. But less examined is how the sounds that producers use are created. The drums that knock in a certain special way, the head-turning keyboard sound, and the “ahhhh” that you hear everywhere? Someone had to create those in the first place, before they could be deployed in your favorite songs.

The process of creating those sounds is called “sound design”—a term that encapsulates not only individual sounds, but also melodies and loops that producers will then sample, rearrange, and add elements to (you can get an in-depth look at that process here).

Sound Oracle got his first break in 2009, coming up with sounds for Polow da Don, which led to a gig with Timbaland. His drums and loops have shown up on songs by JAY-Z, Justin Timberlake, 50 Cent, Drake, and more.

“I saw him really reaching the same way when I reach, when I go try to make a drum,” Timbaland says about his protégé. “I saw his technique on how he really pays attention and really wants to learn. He really digs for the sound and the sonics.”

Sound Oracle often starts with white noise when creating sounds. “You shape and you mold,” he says. “You pitch up amplitudes and frequencies until it sounds like a snare or it sounds like an 808. And from there, you manipulate it more.”

“I have a lot of big producers that buy from me, a lot of legends that buy everything that I make.” - Sound Oracle

Producer Jake One is known for his drum sounds, but instead of working in conjunction with a super-producer like Timbaland, Jake bundles his sounds together into packs and sells them to everyone. His talents are showcased in his Snare Jordan collections of drums, loops, melodies, and other sonic goodies. He has heard his sounds on hundreds of albums: “I can pretty much listen to almost any rap album and be like, ‘Oh, that open hi-hat, that's mine.’”

Jake uses a number of different types of source material to create his magic. In addition to taking drum hits off of existing records and changing them, he’ll sometimes get even weirder. “I might even hear a drummer on YouTube and just snatch that snare and compress it and run it through my process and combine it with other sounds,” he explains. “Or I might chop up seven tom sounds and make a percussion loop.”

!llmind, the Grammy-winning producer whose sound and loop collections are sold under the name Blap Kits, makes new material out of “folders and folders” of sounds he’s collected over the years.

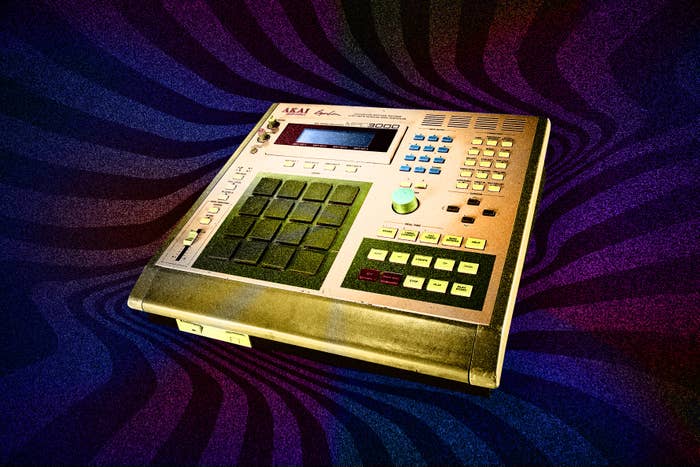

“Some sounds are from old beat machines,” he elaborates. “Some sounds are from live drums. Some are from live percussion sessions where I'm mic'ing up instruments like tambourines, snare drums, or kick drums. And then I take these sounds and import them into a program like Pro Tools and and just manipulate the hell out of it. I'll use compression, I'll use reverb, I'll use layering techniques, EQ techniques to alter these sounds and turn them into something new. It's almost like cooking—I'm taking all these different raw ingredients, and then mashing them up together to create something completely new.”

“I'm not someone who uses presets. I try to make every sound from scratch every time.” - G. Koop

G. Koop goes deeper still, delving into modular synthesis to create new sounds. He frequently uses the word “scientific” when describing his approach, comparing what he does to Malcolm Cecil and Bob Margouleff’s work on the TONTO synthesis system in the 1970s, which powered much of Stevie Wonder’s classic music of the period.

While he laughingly admits it’s “not the most practical way” to make music, Koop says, “I'm not someone who uses presets. I try to make every sound from scratch every time.” That makes his work difficult to recreate, even for him (hence his vanishing sand mandala metaphor).

Koop’s work, sometimes in tandem with Jake, can be heard on “Bad and Boujee,” as well as songs by Rihanna, 21 Savage, and Future. Speaking of Future, the Atlanta kingpin’s latest album Future Hndrxx Presents: The WIZRD features production from ATL Jacob, a young producer who relies on a sound designer. That sound designer (all Jacob will let out, for fear of having his swag stolen by other aspiring beatmakers, is that said person is named Ricardo and is “from overseas”), like Koop, makes his sounds from scratch.

“Back in the days, we had record stores. I feel like now kids are becoming the record stores by making their own samples.” - Timbaland

The two sides of the sound design business—creating sounds for yourself or for one premium client, and putting a bunch of sounds in a pack to sell commercially—co-exist peacefully, often on the same song. Sound Oracle has created an entire company to sell his sound packs, and the business’ clientele may surprise you.

“Big time producers buy sample packs,” Sound Oracle reveals. “I have a lot of big producers that buy from me, a lot of legends that buy everything that I make.”

The idea of producers using sounds from other people has now become big business. Laura Zax is the vice president of marketing for Splice, a company that offers sounds, melodies, and loops to producers using a Spotify-like subscription service—one monthly fee gets you access to their entire library.

The company’s user base isn’t limited to aspiring producers. The main drum sounds on Demi Lovato’s “Sorry Not Sorry,” produced by Oak Felder, come from Splice’s library. Zax says that the company is able to succeed thanks to a new openness on the part of producers and sound designers alike.

“The culture of music has changed so much, even in the past few years,” she says. “In 2016, we would talk about how we wanted to build an open ecosystem for music creation. We thought it would take longer than it did. It turns out that monetizing the act of being open with your process definitely helps accelerate openness.” Zax continues, “But also, with the rise of YouTube, people are used to seeing people pull back the curtain now in a way that they weren't before. It's been less of an uphill battle than we thought it would be to get people to open up their project files and open up their hard drives, and give back to the creator community.”

The ways producers get their sounds and ideas—from kits, from other producers, from sound designers—was on full display at the sessions for Dreamville Records’ Revenge of the Dreamers III. !llmind, who was present, describes the scene. “That was all of us in one studio,” he recalls. “You're talking 20 to 50 producers in one building at one time, and everyone is collaborating. You have guys that are trading flash drives, air dropping melodies to each other, and emailing song ideas to each other. It becomes this big collaborative effort. I think that's kind of what sound design is: It's the art of manipulating sound. Whatever happens to that sound after that, it can kind of go in a million different types of ways.”

While the phenomenon of having sounds available commercially may be comparably new (!llmind, a pioneer in the field, released his first Blap Kit in 2011), in some ways it’s just the latest version of an old story.

Beginning in the mid-1980s, sampling became the cornerstone of making hip-hop. And what is sampling, after all, if not using someone else’s sounds, loops, and melodies to make music? It’s a parallel not lost on Timbaland.

“The model that I see a lot is these kids are mixing with sample packs and sharing music,” he says. “I feel like it's the wave of sharing data. Back in the days, we had record stores. I feel like now kids are becoming the record stores by making their own samples.”

Jake makes a similar point. Addressing anyone who thinks that producers collaborating or gettings sounds from each other is a new phenomenon, he points out that credits during the sample era often didn’t reflect the amount of people involved in making a song.

“If you credited every single record, then we'd have 30 co-producers on every song from those times, too,” he says.

After years of releasing sounds to the public, !llmind now hears his drums all over the place. “Every snare is like my little baby,” he says. “When I hear it, I'm blown away every time.” He ends our conversation with some advice for people who want to hear their sonic creations on their favorite artists’ tracks.

“If you're a sound designer, if you're a producer, just make sure you're honest with your sounds and honest with your music. Ask yourself the question, ‘Am I contributing positively to this culture?’ Just contribute sounds that are original, sounds that are good, sounds that are useful.”