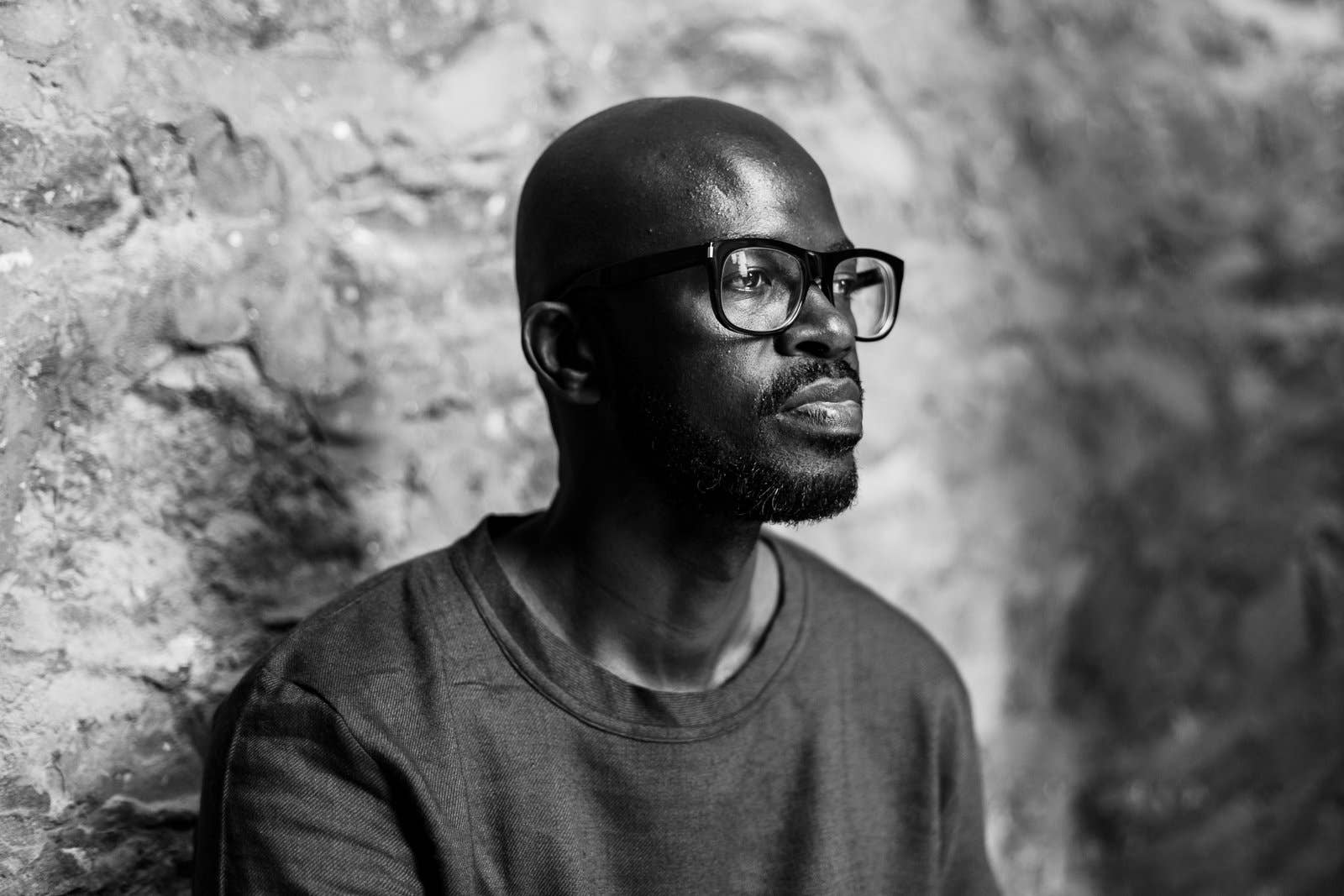

Black Coffee's smooth, soulful music exudes intelligently futuristic vibes. Totally original and dance-orientated, from first play, the South African artist's bumpin' rhythms inspire movement and emotion. The Durban native's aim for his music is to promote appreciation for a wide-ranging spectrum of genres, cultures and races. He asks for his audiences to hear him with an open heart, and mind.

Deeply patriotic, Black Coffee loves South Africa. Happiness feels tangible when he's on the decks, channeling sunshine on skin, passion, exotic roots and his culture though his sound. He believes he was put on earth to make music that would shine a light on the struggles of his community; to encourage compassion, understanding and equality in a world where racial divides have stifled his own progress in the past. Born in a township, where he spent his childhood, then raised by his grandmother in Durban as a young man, Black Coffee now has a family of his own and wants his children to thrive in a fair and free society, a place free from the judgements and constraints he still struggles against as a black man today.

Frequently headlining festivals and super-clubs, Black Coffee was a resident at Ibiza Hï this season—a hugely coveted spot. The introverted 40-year-old producer, and Drake collaborator, has never drunk or taken drugs—despite living by the night's party scene for his whole career. Here is a man dedicated to educating us about love, asking for prejudice and ignorance to be recognised and abandoned so we can all co-exist in a better world: a world that dances and vibes together.

Complex had a catch-up with the man himself.

COMPLEX: In Cape Town, the black/white divide feels greater than in many other cites. Would you agree?

Black Coffee: Everyone I meet in Europe tells me they love Cape Town, but in my head, I know that doesn't mean they have truly experienced South Africa. Cape Town is such an international city; everyone whose been to Cape Town will tell you how European they think it is—which is a good thing, in part. But if you are in Africa, you should feel like you are actually in Africa. Yes, go to Cape Town, but also you must see the rest of Africa.

Do you still feel a divide now, even though you are celebrated as someone special?

It's there. Every now and then, it surfaces—but it's not just in my country. I travel every day and, today, I had two flights to get here [London]. Most of the time I fly from Barcelona to Berlin, I'm the only black person in the airport and I see the looks. I grew up knowing that I'm black, and racism is there, but sometimes it's not in the form of racism—it can be like today. I tried to enter priority boarding with my pass, and the guy didn't even want to look at my boarding pass. He said, "Go back to the normal queue." Nowadays, when I travel, I am always on my toes—always ready for what could happen. I told that same man, "I am priority boarding now, so please don't waste my time." He wasn't happy. Then I sit on the flight—I'm quite tall, and the guy behind me is tall too—and as soon as I start reclining, there is tapping on my chair and a voice says: "You must sit back up right now!" I always stick up for myself, but this was so awkward. I then get reported to the flight attendant, who says: "It's okay. He has a right to push back his chair." So to cut a long story short, I'm used to these kinds of things happening. I'm from a place where there is black and there is white, but I have to keep on pushing on.

Do you find people treat you better when they see your material worth?

Definitely! What you possess changes everything.

Does that heighten your resentment of people in general?

I try to not let it; if you pay attention to people who have a problem, you have the same problem. In Greece, most black people sell fake Louis Vuitton bags on the beach, so a typical Greek person is going to assume that's how society works—that's what black people do. So, it's how I navigate my way through that problem, that keeps me sane. I used to be very paranoid when I walked into a shop and no one helped me. I thought they assumed I was there to waste their time, so I would retaliate and buy the most expensive item that I didn't even really need. A friend of mine did the same thing, subconsciously. He collects watches—he has a lot of them, which are all timepieces—and that's how we initially became friends: for our equal love of watches. He told me about a guy who comes regularly to his house to sell designer watches to him privately, and, sometimes, he will buy all of them. I asked him why. The problem is, we are both so scared of people believing we cannot afford what is for sale. But it's okay to say, "No, I don't want to buy this today." That was a journey I had to go through.

I think, on the flip side, it's not that different for a woman. If you're travelling somewhere expensive, own something particularly costly or sat in a bar alone wearing a nice dress, people commonly assume that you're funded by a man.

It happens with my wife a lot. When she drives her own car, or any of mine, the comments she gets is ridiculous. And she works herself! The assumptions are that she must have a Sugar Daddy, but I say to her all the time: "Do not even respond." If I walk into a shop and you think I'm there to waste your time, I should not respond by buying. There's a shop here in London that sells classic leather jackets; there's this one I love right now, which is £4,000. Sometimes you want something, and sometimes you need something—but I don't need this. I was in Berlin last night and I saw that same jacket and I still said no, but it's taken me a long time to get to that place.

How do you hope to represent your country on a wider scale?

So many South Africans will mention my name and, for me, that is so powerful. A simpler example is, there is a lady I know who is in a wheelchair, the wheelchair is motorised, and she had problems so she posted on Twitter saying she needed a new wheelchair. She said she would like to work for it—the chair she needed cost way more than she could afford, about 6,000 euros—and she said: "I make beads, so I want to create beads and sell them to contribute." I saw this and it really touched me so I spoke to her privately on Twitter. I asked her how much she had raised and it was only 150 euros. I told her I would double the amount of money she had and that we would go and find people to create a big batch; the 300 euros would then pay for the materials. I told her I would get her the wheelchair so she could pay the people who would help out with manufacturing—paying them with the money she made. I told her, "I'm going to take all the beads you make and give them away at the closing parties in Ibiza."

So we spoke and she was really excited and started working on the beads; she didn’t speak me with me again until she was done. By that time, someone who had seen the story online had brought her the wheelchair! But I still wanted to help. Every year, I want her to be my supplier. I want to give these beads away at shows so people can have a part of my country, and this is what I'm talking about: when I play, it's a night of music, but it's also important that it comes from this place, my home. I want to find things that are premium about my country and showcase them to them world.