If you want to better understand an artist and their work, a biopic is one of the worst places to start. But Hollywood insists on making them, and we watch them because it’s undeniably thrilling to witness a performer inhabit a familiar stranger, like Jamie Foxx as Ray Charles in Ray or Angela Bassett as Tina Turner in What’s Love Got to Do With It. The conventional artist biopic is a vehicle for performance—almost like a late-night show’s impersonation, but with a budget and sincere conviction—rather than a means to gain real perspective on the cultural context the star emerged from, the musical history that informed their particular style, and the ideas that fueled their creativity. The stories told in these films—because they have to get in and out in two hours time—are always too logical to accommodate the question, why create?

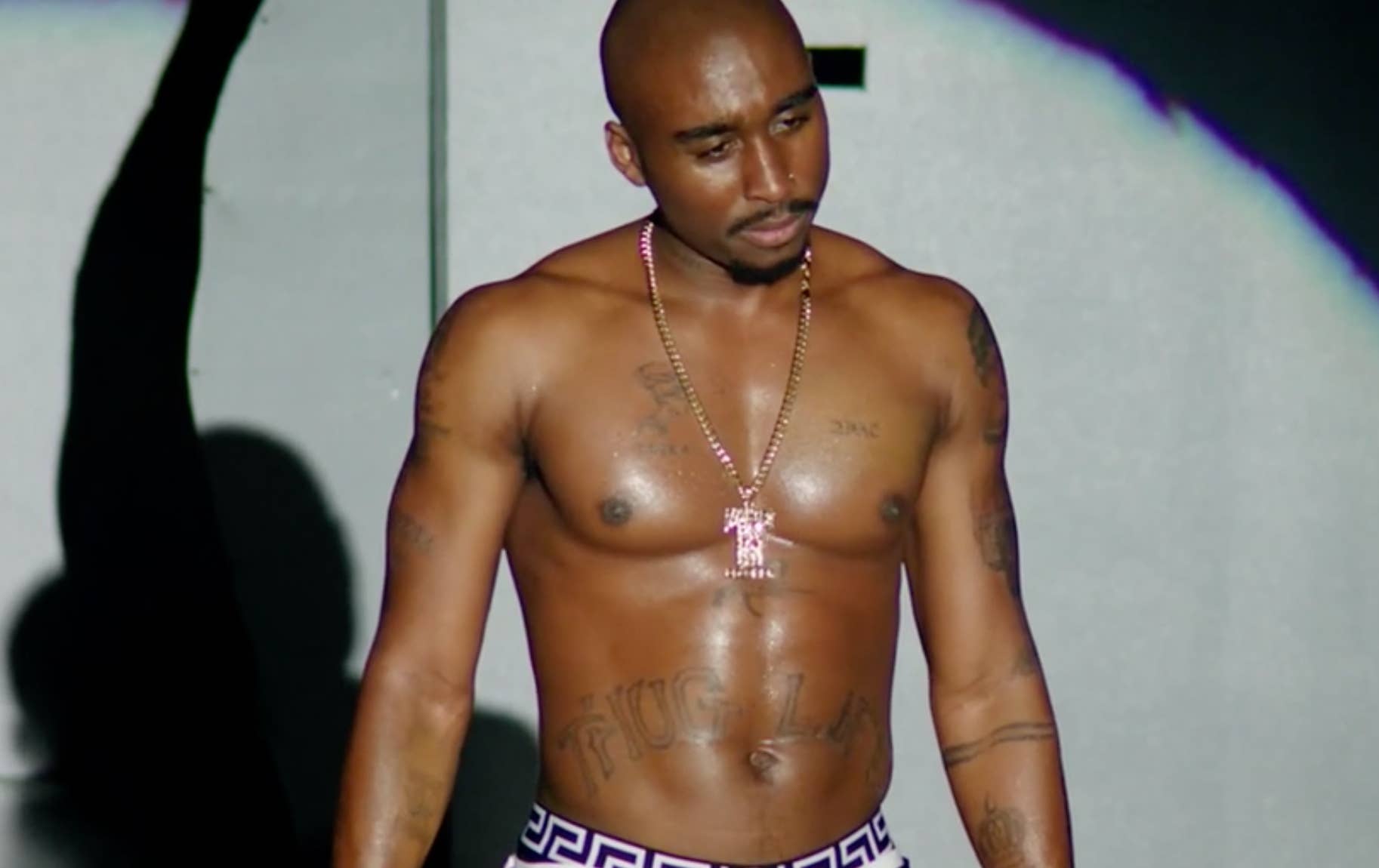

I have yet to see the Benny Boom-directed Tupac Shakur biopic, All Eyez on Me, but the trailer suggests that it will be a straightforward depiction of Shakur’s life, from a young boy raised among black revolutionaries to the rap star at the center of the East-West divide. Virtually all biopic trailers (and the movies themselves) hit the same story beats. There’s the hushed build-up before the revelation of the lead made up to look like the star we adore; there’s the childhood incident that will shape the artist’s life to come, and then there’s all the trouble, be it drugs or booze or love or some other form of abuse. What’s Love Got to Do With It. Ray. Walk the Line. Get On Up. Now, All Eyez on Me.

These stories bet everything on the uninspired logic of cause-and-effect as the key to unlocking the life and work of our most talented creators and interpreters. A.O. Scott, film critic at the New York Times, described this approach as the “literal-minded, anti-intellectual assumptions that guide even the most admiring cinematic explorations of artists’ lives.” Ray Charles watches his brother die in an accident before losing his sight. He emotes in his music and struggles personally because of the trauma. Johnny Cash loses his brother in an accident, and then emotes in his music and struggles personally because of the trauma. Other forces work on our heroes, too, but there’s a dulling sameness to the story arcs. If you listen to their music, though, you just feel that their genius is being done a disservice with these pat summaries.

Documentaries and miniseries, with their longer runtimes, create room for greater complexity. For instance, Ezra Edelman's O.J. Simpson doc, O.J.: Made in America, makes a coherent argument about Simpson’s life, symbolic significance, and why his trial became a kind of jeremiad for police violence and injustice against the black community in Los Angeles, but Simpson never becomes totally legible to the viewer. Instead the viewer encounters a variety of Simpsons—the smooth talker his boyhood friends remember, the upstanding “credit to his race” the white execs saw opportunity in, the violent abuser Nicole Brown’s family will never forget, among more incidental iterations. The divide isn’t so simple as private vs. public, and there’s no reconciling every side.

It’s possible to fragment a person as they naturally are in a fictional work, but it calls for fragmenting form—something biopics rarely do. Selma, for instance, is remarkable because it’s only a fragment—by focusing on a particular moment in time, it allows access to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in a way the avoids the clichés of formulaic storytelling.

Tupac Shakur would benefit from a more formally adventurous approach, since he’s already an American myth, and we’ve yet to get a truly great rap biopic.

Tupac Shakur, in particular, would benefit from a more formally adventurous approach, since he’s already an American myth, and we’ve yet to get a truly great rap biopic, even though rap music is the most innovative and important development in popular music since rock and roll.

Notorious and Straight Outta Compton are the most high-profile hip-hop biopics, and neither reach the level of artistry that they seek to explain. F. Gary Gray’s depiction of the rise of N.W.A. comes closest but is hamstrung by some limp performances, too much plot to sprint through, and an unwillingness to dig into the more difficult aspects of its characters, especially Dr. Dre and Ice Cube (both of whom were heavily involved in the film, financially and creatively). Much of the debate around the film had to do with the omission of Dr. Dre’s history of abusing women. Imagine a film that was bold enough to interrogate misogyny in the context of rap history. Straight Outta Compton is most necessary when recreating their incendiary live performances and studio recordings—in other words, it understands the music, but doesn’t bring the same curiosity and awe to the lives of the artists.

By cutting the conventional script to ribbons, Todd Haynes’ I’m Not There is easily the most interesting artist biopic. Like ‘Pac, Bob Dylan is a sort of mythological being and instead of giving us the highs and lows of his life, Haynes does something more like music criticism. He splinters Dylan into different approximations that riff on the myths that inform how we hear Dylan’s music, the times that produced him, and how we wrestle with his legacy today. In other words, the story and its form are dictated by Dylan’s persona and art, rather than putting his biographical info into a ready-made, easy-bake narrative pan.

Imagine a Tupac Shakur biopic that was willing to, like Selma, imagine the big picture in one moment—like Shakur’s time in prison. Or one that let the sample-based, collaborative nature of rap production infuse the story being told on screen. The genre is experimental, so why not the art about it?

In many ways, Shakur was just as fractured and contradictory as Dylan. He was a charismatic, eye-catching dancer and actor, sensitive and sometimes goofy. Through sheer force of will, he turned himself into a larger-than-life gangster, and lived that life violently, shooting at police and taking bullets himself. At 23, he was sentenced to 18 months in prison for sexual abusing a female fan, and in the courtroom he addressed the judge, saying, “I mean this with no disrespect, Judge—you never paid attention to me. You never looked in my eyes." He was a canny performer and had a seemingly intuitive understanding of image. His voice alone could tap a vein and birthed a passionate following that hasn’t diminished with generations. What his myth means now is as flexible and agile as rushing water. It shouldn’t be fixed.

Those are broad, simplifying strokes, but even they suggest avenues for an ambitious filmmaker to explore. One of the other qualities that makes I’m Not There work is its interest in film and filmic allusions as a means of illuminating cultural context—something a Shakur narrative could easily replicate. The softness of '80s music videos giving way to the grainy look of '90s hood films, Miramax indies, the nightly news, and the advent of more affordable and portable personal recording devices—there are myriad visual palettes and tropes available for a film that wants to unpack Shakur in the context of the L.A. Riots and the Clinton presidency’s Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. There are multiple genres available, too: prison B-movies, the outlaw western, the gangster picture, the musical.

As the culture evolves and we take a more intersectional approach to what’s valuable and exhilarating about the legends of the past—especially in hip-hop—innovative storytelling should be more important than creating a visual Wikipedia page with a craft budget. For an artist as significant, talented, and multifaceted as Tupac Shakur, it’s the correct thing to do. But it’s unlikely that we'll get it.