Hunched over his laptop, Willo Perron is scrolling through a digital mock-up of an unreleased project for Jay-Z’s 4:44 album. Over several peach-colored pages, in simple black Larish Neue font, there are release dates for 4:44 in different countries, photos of the 4:44 ads plastered on billboards, buses, taxis, and subway stations that teased the rapper’s thirteenth studio album, and more. “It’s really a manual for the 4:44 brand,” he says, sitting in his West Hollywood studio on an October afternoon.

Perron, a multi-disciplinary designer and director, collaborated with Jay-Z to concept the packaging and creative direction for 4:44. He designed the album artwork and played a seminal role in the brilliant rollout that included the mysterious “4:44” ads and the black and white teaser starring Oscar winner Mahershala Ali, which premiered during the 2017 NBA Finals. “We went through a few other iterations of what the record was going to be called,” Perron says in his first extensive interview. “When we landed on 4:44, I was like, ‘It’s just this color and these digits.’ We wanted to do a really didactic campaign.”

While he won’t say much about it, he also designed the set and stage visuals for the official 4:44 Tour, which kicked off late last month. During the show, Jay-Z performed on an octagonal stage, placed in the middle of the stadium, with eight vertically-suspended screens hovering above him that showed various camera angles from the stage and footage of peers and family, some of which he erased himself from.

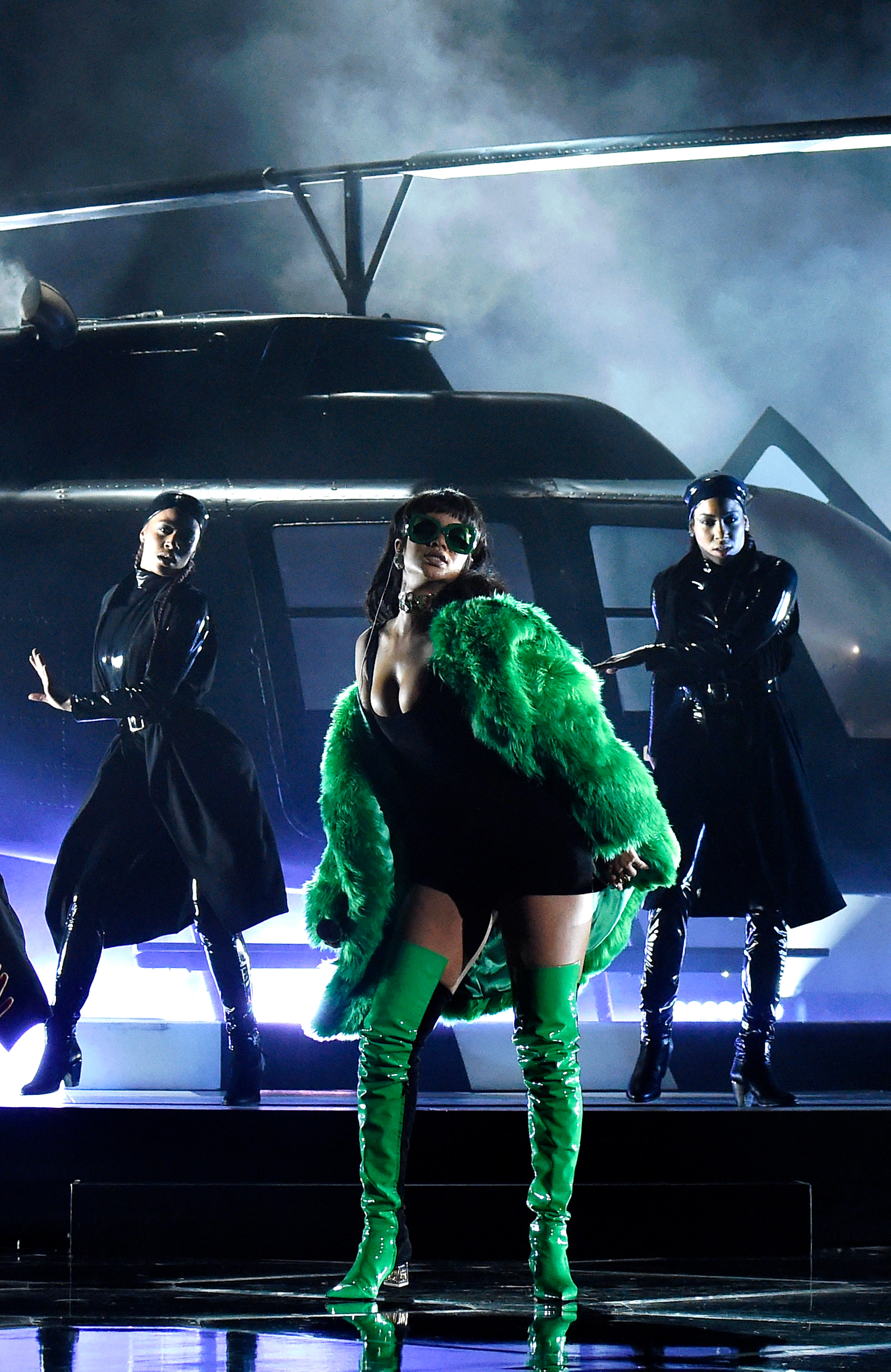

Perron first worked with Jay-Z on the rapper’s 2012 American Express UNSTAGED performance at South by Southwest. But he’s been behind the scenes of other memorable album covers, live shows, retail spaces, and videos for years. In 2008, he worked on Kanye West’s critically acclaimed Glow in The Dark Tour. Rihanna has enlisted him to creative direct many of her performances, including her Diamonds Tour, ANTI Tour, and her 2016 MTV Video Vanguard Award production. “I guess after years of successful Kanye and Rihanna stuff, you eventually get that call [from Jay-Z],” he says. He also designed the set and stage visuals for Drake’s 2013 Would You Like A Tour? and built several of Stüssy’s retail locations. Most recently, he was responsible for the blockbuster Nike x NBA global launch, where the league’s new jerseys were revealed behind three moving big screen monoliths.

The titles creative director and art director have become commonplace today. Nearly all of the top acts in music have at least one consigliere in their team. The Weeknd has La Mar Taylor. Mike Carson oversees Big Sean’s project. West, over the years, has built an entire team of collaborators under Donda, his well-regarded creative company. But when Perron first worked with West, the profession didn’t exist. He didn’t set out to become one either. “Back in the day, I think that was more management in the artists’ ears,” he says. “I don’t think anyone really cared about titles, but I was like, ‘If I’m going to do this everyday, with this guy, it can’t just be ‘Kanye’s entourage has a couple creative guys in there.’ It felt like a lack of respect for the craft. But it definitely wasn’t intentional.”

“Willo is the original,” adds Matt George, the man behind streetwear emporiums Nomad and Stüssy in Toronto and Vancouver. George has known Perron for almost 15 years and has worked with him on various projects, including Stüssy’s brick and mortar locations. “Willo’s one of the guys that made that term synonymous with these kids. You hear people all the time now say they’re creative directors, but he is the truest sense of that word.”

For the last two decades or so, Perron has masterminded some of the biggest projects, for some of the biggest artists and brands in the world. But after all the success, where does he want to go from here?

Perron is much more inconspicuous than the well-known names he works with. Dressed in a plain white T-shirt, navy blue trousers, and a pair of grey New Balance 992 sneakers, he has wispy brown hair combed over to the right side of his head and a grey beard. He could pass for any 43-year-old who lives in L.A.

But, as he tells it, he’s always had an appetite for art, fashion, and design. He was born in Montreal, the son of a pianist and a psychologist who loved to play the piano, sing, and paint. As a kid, he attended the performing arts school Fine Arts Core Education (FACE) or, as he calls it, “the Fame of Montreal.” “Every second class was an art class,” he remembers. “We’d go to English and then band practice.”

He dropped out at 14—“I was miserable, but luckily I had very understanding parents,” he says—but continued to immerse himself in the creative field. He studied books on German-American architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and other mid-century and modern architecture that his older brother found at thrift stores. He taught himself graphic design and video by reading books and going to “weird” Polish film festivals. He was inspired by Stüssy and Freshjive founder Rick Klotz. By 19, he was designing for Rewind, a local snowboard brand, and Lithium, which he describes as “post-wave, early clubwear”—gigs he says he landed by simply being “one of the kids who did everything in the city.”

For the next few years, he ping-ponged from one job to another. In his early 20s, he opened an indie hip-hop record store called Science in Montreal and later founded Audio Research Records with A-Trak, Dave 1 of Chromeo, and Vice co-founder Suroosh Alvi. (Audio Research folded in 2007.) Then, in 1997, he moved to Los Angeles and designed for snowboard/outerwear label Dub and skate brand Droors, which were both owned by D.C. Shoes. Two years later, he became the creative director at New York hip-hop label Rawkus, previously home to Mos Def, Talib Kweli, and Pharoahe Monch. By the time he relocated back to Montreal in 2002, he owned several local shops—an audio store (Moog), a sneaker shop (Goodfoot), a men’s multi-brand streetwear retailer (Eskimo), and a women’s multi-brand brick and mortar (Mosquito).

That same year, he began designing retail stores for American Apparel. Perron and Dov Charney, founder of the basics brand, hadn’t seen each other in years. But one day, Charney unknowingly stumbled into Perron’s new design studio in Montreal; He was in awe of the space. “Dov walked in and was like, ‘This is cool! What the fuck is this?” Perron says, mimicking Charney’s raspy voice. “I turned around and it was Dov. He was like, ‘Ah, Willo! It had to be you. What have you been up to?” He told Charney about the shops he owned and walked him to each one. Impressed by what he saw, Charney invited him to design stores for American Apparel. “We took the space next door to one of my stores and built the first American Apparel location,” says Perron. “The day we opened, it was mental.”

He traveled all over the world—to Korea, Miami, et cetera—and opened hundreds of other American Apparel brick-and-mortars inspired by the Italian design book, High-Tech: The Industrial Style and Source Book For the Home, weekly. “It was fucking great,” he says about the experience.

But after three years of building retail stores, he was burnt out. “It was a whirlwind,” Perron says. “I was over everybody.” He needed to get out of Montreal. So, even though he swore he’d never return, he flew to L.A. to visit a friend. To his surprise, he liked how much the city had changed. The short trip eventually turned into a more permanent move, and he sold his stores and house in Montreal.

A week after moving to the city, he got a call from Apple. They wanted him to help with a few retail projects. Perron agreed, but quickly learned he wasn’t cut out for the corporate world. “I went from rolling by myself and hiring whoever I wanted at American Apparel to dealing with this established, political machine,” he says. Less than a year later, he quit. “I didn’t fit in very well.”

He eventually fell into something more suitable. In 2006, he met Kanye West at Kuala Lumpur, the capital city of Malaysia, after the last show on his Late Registration Tour. “At this point, he had College Dropout and Late Registration,” he says. “We just met at this opportune moment when he was trying to elevate his thing past jersey rap.” They clicked instantly, and began working together. “I was a kid who grew up in Canada, in a poor family, who loved rap music and museums,” he says. “It didn’t make sense to a lot of people, but he got it.”

Perron’s first task: help West with his wardrobe. “I went to his house in L.A. and he took me downstairs to a closet the size of a room,” he remembers. “He was like, ‘Take everything that you don’t like out.’ I was like, ‘Are you sure? There won’t be a lot of shit left.’” Perron gazes out the window and, as if he’s back in that exact moment, lets out a chuckle; West’s request is still amusing to him today. “He had his crew—Don C and Ibn[Jasper]—and those guys were really into Bape, Pharrell’s stuff,” he continues. “I was the opposite voice. I was much more into Comme des Garçons, [Maison]Margiela, and well-tailored stuff. But Kanye was like, ‘I’m serious. Take everything you don’t like out.’ So I started pulling shit out. Hundreds of stuff. Some of it, like the Bape Shark hoodie, made it back.” The following week, Perron brought a seamstress to West’s house to tailor the rapper’s clothes.

West, perpetually drawn to people who share his interests and know what he doesn’t, welcomed Perron into his coterie of friends and collaborators. Perron wound up working on “pretty much everything,” including the 2008 Glow In The Dark Tour, alongside stage designer Es Devlin, lighting/set designer Martin Phillips, and catalyst/LED technician John McGuire. “Ye drove that,” he says. “I was more the observation and polish guy.” In the years that followed, he also creative directed his performances for the SNL 40th Anniversary Special and his four-day residency at the Louis Vuitton Foundation; directed a montage film for his MTV Video Vanguard Award; creative directed, photographed, and designed the 808s & Heartbreak cover; and designed the Yeezy Season 3showroom.

“Kanye is a great musician and creator,” he says. “He’s inherently super curious and super involved. I just helped him usher in something else. It was more of: I can influence him by giving him information and he can pick what he wants out of it. But it’s 100 percent him. Anybody who wants to be like, ‘I’m a creative director for Kanye…’ It’s like, no. You’re not. Maybe you helped him figure out his shit, but it’s really him.”

Perron has become known for his work on live shows and tours. But, ironically, neither were initially part of his plan. “I never even thought about doing that,” he says. In hindsight, though, it made perfect sense. “I worked as a clothing designer, designed interiors and spaces, and worked in music,” he continues. “It was everything that I knew, put together.” Soon, he got calls from other tops acts, including Lady Gaga, Rihanna, Drake, Florence + the Machine, Bruno Mars, Miguel, Katy Perry, and Jay-Z.

At a restaurant a few blocks from his studio, Perron is getting worked up about Bic lighters and pens. His eyes beam with excitement and his hands are extremely animated. “It’s genius!” he says, as he raises his voice and flings his hands in the air. It’s a strange obsession, but not for Perron, who says he “loves essentialism.”

“I like people that do one thing really well, things that are truly proven,” he says. He lists Clarks Wallabees, Levi’s 501 jeans, and Converse All Star sneakers as examples. “For me, to land one of the absolute classics is the ultimate achievement in design.”

It’s funny then that, unlike his personal taste, much of his work is the complete opposite—especially given that he even launched Invisible Tailor, a line of unisex leather jackets inspired by his admiration for essentialism, with George and fashion designer Steven Alan in the late-2000s. They’re often ephemeral, and deal with the collective conscious or what’s happening in the news. “My work comes from research and where are right now,” he says. “How do we tell a story now?”

“Who cares if people don’t like my stuff? Hopefully it’s polarizing enough that it upsets people."

He likes to indulge in what he calls “throwaway ideas.” “Everything starts with a bit of a sense of humor,” he explains. “You have to be like, ‘What’s so throwaway that you wouldn’t expect it to be here?’ You throw the most absurd idea at the wall and see what sticks, and that narrows down to something else and we land on something that makes a little bit more sense. But the ability to put out something that’s meant to be consumed and disposed of really fast is interesting to me.”

Once, he suggested directing a subtitled Korean gangster film starring Drake for the rapper’s Would You Like A Tour? The short movie—one of many “absurd” ideas he’s thrown around—would be played on the massive backdrop screen during the show. There was no real inspiration for it, just that he thought Drake had “great acting chops” and the aesthetic of these dark, saturated films “fit him really well.” “We actually kind of went down that road in the beginning,” he adds, “but then about halfway through he decided he didn’t want it to be so conceptual.”

Perron approaches each project differently, and there’s often no formula for his work process. Some partnerships are collaborative, while others are simply “me in a black vortex.” But what is consistent is the tremendous amount of research he does.

For any given project, he’ll often comb through hundreds of visual references. The treatment for the Magna Carta… Holy Grail album packaging, for instance, includes various images spread over different mediums. Among them: A mood board with photos of NWA, Mike Tyson wearing a sweater that reads “Property About Law, words in Hebrew, and a field of crosses; “Shawn Carter” in Hebrew; photos of bottles of Tom Ford cologne; screenshots of propaganda videos; iconic images by Daidō Moriyama, Ari Marcopolous, and Tyrone Lebon; and stills from various animated short films including the 2009 Dock Ellis and the LSD No-No by James Blagden. “We really liked Dock Ellis and the LSD No-No, and we were going to do this animated film, which happened on 4:44 instead,” he notes.

“Willo’s the type of guy who will disappear for days and just watch a million documentaries and books, if he’s feeling uninspired,” says George. “The amount of research [he does] is immense.”

He doesn’t have a database for references either, so inspiration can come from anywhere—movies, conversations, books, photos he discovers on Instagram or the internet, and dreams. Once, after waking up in the middle of the night, he came up with the idea to design a set with a black helicopter for Rihanna’s performance at the 2015 iHeartRadio Awards. That’s also how, he says, Jay-Z wound up wearing a Colin Kaepernick jersey on Saturday Night Live last month. “I woke up and was like, ‘Kaepernick jersey. SNL,’” Perron remembers. “Jay was already in the zone. He dedicated ‘Moonlight’ to Kaepernick at the [Meadow Music and Arts] festival the weekend before, he just turned down the Super Bowl, so it was like, ‘Ok. We’re already in the fucking sauce. Let’s go deeper in the conversation.’”

Ultimately, his objective is to make sense of uncommon pairings. “A really big part of my research is to bring things together that aren’t necessarily obvious together,” he explains. “You start seeing patterns in things and formulate languages and logics that weren’t there before.”

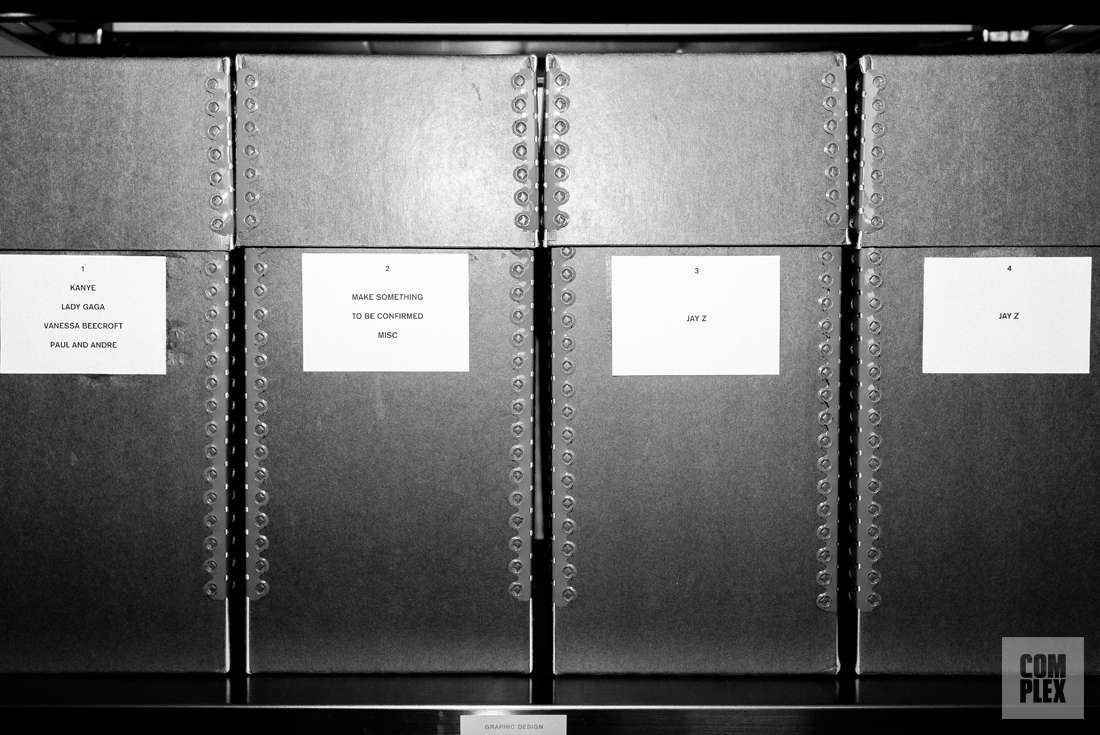

On a steel shelf in Perron’s studio, there are grey file boxes labeled, in black capital letters, with names of people he’s worked with. Among them: Jay-Z, Drake, West, Frank Ocean, Marilyn Manson, Bruno Mars, The XX, Coldplay, St. Vincent, and Lady Gaga.

Over the years, he’s become a go-to for many big-name artists and brands. What’s more, he’s helped birth a new generation of kids who consciously set out to become a musician’s creative director—an occupation Perron says didn’t exist when he first started working with West. “It feels common now, but we invented that thing,” he says.

But he’s not focused on accolades, or whether or not people admire his work. “Who cares if people don’t like my stuff?” he says, perked up on a faded tan leather couch in his studio. “Hopefully they think it’s shit. Hopefully it’s polarizing enough that it upsets people.”

His goal is much bigger. “I want there to be a conversation around my work,” he adds. “I want to start conversations about what’s possible to change within mediums. People should have guts. I’d rather see something that’s really ugly that tried to do something than just not trying at all. That’s more respectable to me. I’ll find something in that that I love.”

Soon, Perron will move into a new and bigger office in Silver Lake in L.A for Willo Perron & Associates, the design studio he founded roughly seven years ago. His team will double in size. He’ll have an art department, and staff dedicated to interior architecture and live shows. “I really want to take it seriously and spend a lot of time building shit,” he says. “Plus, it’s a better place for me to age into.”

More importantly, the new space will allow him to continue to work in various mediums. “It’s not reliant on one thing,” he says. “It’s like a web. We’ll do videos, interior projects, print or campaign projects, and not just have to do tours.” There’s much more he’d like to accomplish.

But after decades in the industry, what is he most proud of? Perron looks around the room and chuckles, unsure how to answer. “That’s a bizarre question,” he says.

After a short pause, he tries again. “If I’m proud of anything, it’s that we helped bring legitimacy and artfulness to mainstream media,” he says. “Kids go to museums because of us. We fucking design books.”

“But there isn’t this mountain you climb that you get to the top and that’s it,” he adds. “It’s continuous. I think about my career more as a punchline to a joke at a dinner party. This is going to be a moment that was great, but it doesn’t define me. There’s going to be a bunch of shit before and after.” And just like that, he has to get back to work. Jay-Z’s team is waiting for his call.