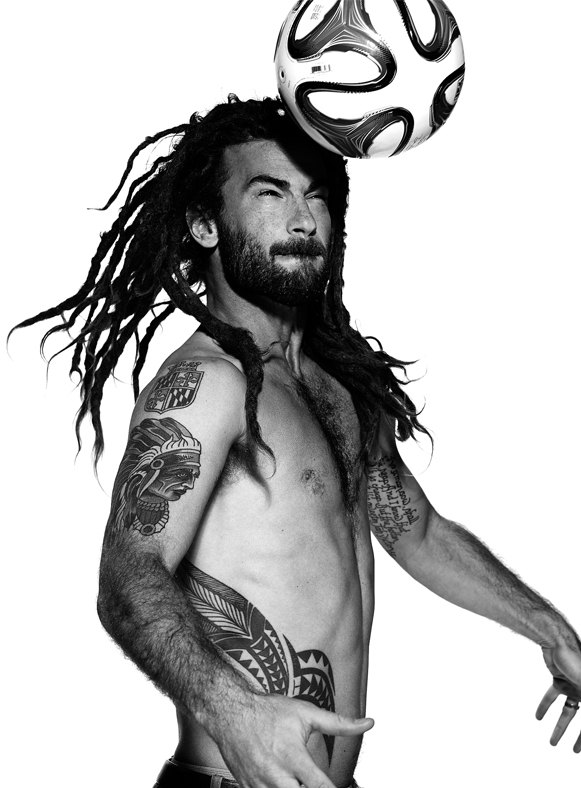

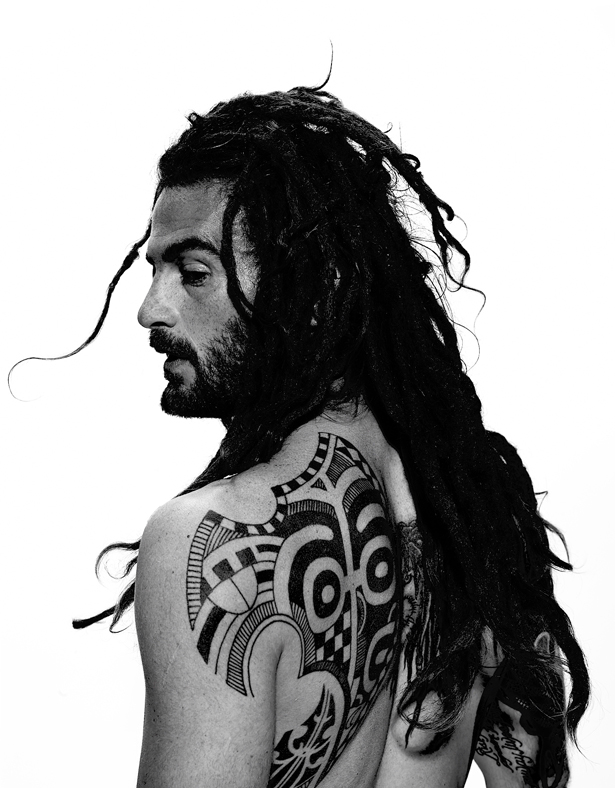

Kyle Beckerman / Can He Kick It? 0%

Kyle Beckerman / Can He Kick It? 0%

SINCE HE WAS 8 YEARS OLD, KYLE BECKERMAN HAS BEEN DREAMING OF PLAYING IN THE WORLD CUP. HE DIDN’T MAKE THE U.S. SQUAD IN 2010, SO THIS MAY BE HIS LAST SHOT...

Written by Adam Silvers • Photography by Zach Gold

By last October, the United States Men’s National soccer Team had already secured its place in the 2014 World Cup. The Americans had a final match to play in the qualifying rounds, a road game against a Panama team that could stamp its own ticket to Brazil with a victory. But the USMNT didn’t need a win—in fact, a loss would ensure that their bitter rivals Mexico missed out on the Cup altogether.

“It was a strange circumstance, one I’d never been involved in,” Kyle Beckerman, midfielder for the US team, recalls later. “We were already qualified. They needed to win.” Panama led for most of the game, until the U.S. tied the match on a corner kick early in the second half. But with less than 10 minutes left in the match, Panama pulled ahead 2-1. With time running out, playing in a hostile stadium, in a game that didn’t affect their own qualifying status, the Americans could be forgiven for hanging back, letting Panama win, and forcing Mexico to miss their first World Cup since 1990. But Beckerman and his teammates had a different idea: “The way we looked at it is, ‘If we’re coming to play, we’re coming to win.’”

In the 92nd minute of the game—two minutes past the end of regulation, during extra time—the U.S. knotted the game at 2 on a header by Graham Zusi. At that point some of Panama’s players began urging the Americans to take their foot off the gas. “It was weird,” Beckerman says, shaking his head. “You just don’t do that.” Ignoring their pleas, the U.S. completed the comeback a minute later when second-half substitute Aron Johannsson crushed a shot from outside the penalty box into the lower left corner of the goal, winning the match 3-2.

The next day, Mexican soccer fans were effusive in their gratitude toward the USMNT. For U.S. soccer, a program that’s essentially just 24 years old and still fighting for respect on the world stage, it was a new role—playing the bully instead of the upstart. Jogging off the field that night, Beckerman explained the sentiment behind the effort of the American team—and his own: “The United States may be going to the World Cup, but I might not be. I can’t take it easy, bro!”

The summer of 1994 was notable for many things: the withdrawal of Russian and American troops from Berlin, the O.J. Simpson trial, the release of Craig Mack’s “Flava in Ya Ear.” It was also the year that the U.S. hosted the World Cup, and modern soccer in the U.S. was born. Led at the back by the no-nonsense defender Alexi Lalas—with his long orange mane—and at the front by versatile midfielder Cobi Jones—with his trademark wild locks—the USMNT combined a counter-attacking style of play with a strong physical presence to forge the identity of the American game. Not only did they establish the U.S. brand of soccer on the pitch, they brought the game to a broader American consciousness in the process.

Expected to host but not make an impact on the tournament itself, the United States had to fight for respect both on the pitch and off. The team reached the knockout stage for the first time since 1930, and gave eventual champions Brazil all they could handle in the Round of 16 before succumbing in a 1-0 defeat in front of 84,000 spectators at Stanford Stadium. Twelve-year-old Kyle Beckerman wasn’t at that game, but he did convince his parents to make the trip to RFK Stadium in Washington D.C. for a match between Saudi Arabia and Belgium in the group stage. “It wasn’t a headlining game,” he remembers, “but a really good goal was scored by Saudi Arabia and it was an awesome experience to be a part of it.”

Born in suburban Crofton, Maryland, Beckerman started cultivating his signature dreadlocks at an early age. His hair first started knotting up in middle school, and while he didn’t mind being the proverbial “white guy with dreads,” his mother wasn’t so crazy about the idea. “I’d have maybe one or two,” he recalls. “Mom would find out and she’d be like, ‘Get in there and rip those out.’” But as with soccer, so with hairstyles: Beckerman has always understood the power of persistence.

In 1990, while other 8-year-olds were engrossed with Super Mario Bros, Beckerman started taping World Cup matches on his parents’ VCR. The United States was playing in the tournament for the first time since 1950. “I watched every match on video,” he remembers. “The U.S. played a great game against Italy. It was the first time in ages we’d been to the World Cup.”

Four years later the U.S. hosted its first World Cup, and Kyle covered his bedroom walls with posters of the U.S. team’s biggest players. “Tony Meola, Alexi Lalas, Eric Wynalda, Tab Ramos—they were all heroes to me.”

Beckerman told himself that he wanted to be a pro when he grew up, but he didn’t really know what professional soccer was. Major League Soccer had only been founded the year before (in part to attract the World Cup), and wouldn’t start play until 1996. What he really meant was that he wanted to be on the national team. “I just wanted to wear the awesome uniforms,” he recalls. Even the ’94 squad’s infamous denim kits didn’t dampen his enthusiasm. “It didn’t matter what the jersey looked like. It’s the crest—that’s what it’s all about. If that crest is there, the jersey is going to work.”

A standout player at Arundel High School, Beckerman traveled with the U.S. junior team to New Zealand in 1999 to play in the Under-17 World Cup. The U.S.’s participation in the tournament was part of a larger strategy to establish American soccer on a global level. “The goal was to win the World Cup in 2010,” he says. “That involved huge youth investment. We were sent all over the place—Germany, Austria, you name it. We were just little high schoolers, but we had this mindset that we were representing U.S. soccer. We wanted to show everyone that we can play soccer in America. We were naive, but when we were going against big soccer countries we thought, We’re going to kick their butt. We were able to beat a lot of countries. We took a lot of skins.”

Beckerman signed with the fledgling MLS the following year, skipping college to join the since-defunct Miami Fusion. He moved to the Colorado Rapids in his third professional season, and was traded to his current club, Real Salt Lake, in 2007. During his career, Beckerman has seen MLS grow from an afterthought into a healthy, expanding entity. “When I first got into the league there were 12 teams, then we went down to 10, and there was nobody in soccer stadiums,” he recalls. “Now we’re at 19 teams, and we’re packing out crowds.”

Despite being a five-time MLS All-Star and captaining Real Salt Lake to the league championship in 2009, Beckerman was not selected to play for the national team at the 2010 World Cup. As in other countries, America’s top professional players compete for spots on their respective national teams. Beckerman refuses to speculate why then-coach Bob Bradley didn’t pick him for the 2010 squad, which lost to Ghana in the Round of 16. “When it gets to the national level everybody’s good,” he says. “So it becomes coach’s preference. I wasn’t in his plans, and that’s just the way it is.”

This time around Beckerman will be making his Cup debut under new coach Jurgen Klinsmann, who appreciates his persistence and work ethic. “Kyle is a role model of maximizing everything he has,” Klinsmann has said. “If I need someone to point to and show another player how to maximize your potential then you look at Kyle, because that is why he is here.” Leading by example, Beckerman lets his play and work ethic do the talking.

Beckerman isn’t just well-suited to be the flag bearer for Major League Soccer in the United States; the role was tailor-made for him. There are other stars on the team: midfielder Michael Bradley, forward/attacking midfielder Clint Dempsey, and winger Landon Donovan. But Beckerman is the anchor of the US midfield—and he’s spent 14 years fighting for club and for country, at home and abroad.

Although he played for the U.S. in last year’s Gold Cup—the tournament that decides the CONCACAF championship—as well as the World Cup qualifiers, Beckerman’s main goal has been simply to win a seat on the plane to Brazil, right up until the lineups were announced last week. Now he’s ready to put aside his humility. “We want to go there and try to rock the boat a little,” he says. “We want to see if we can do something special.”

A defensive midfielder by trade, but more than adequate at taking an advanced role when called upon, Kyle Beckerman plays a position known as a “holding midfielder” that’s all guts, little glory. “It’s big in transition,” he explains. “You’re going to start the transition from offense to defense. You do a lot of scrappy work. One of the biggest things about that position is to make people around you better, to make their job a little bit easier, so that your attacking midfielder can get more space, get the ball in a better spot.” He says he enjoys the position, “but it’s a lot of grind work.”

The holding midfielder’s contributions might not show up in the postgame stats, but he can be the player who brings a winning team together. Since his move from Colorado in 2007, Beckerman has made 180 league appearances for Real Salt Lake, who won the 2009 MLS Cup after sneaking into the playoffs with the last Wild Card spot in the Western Conference. Even more impressive, their improbable victory came on the heels of a disappointing home defeat in the conference finals a year earlier.

Despite the time he spent with the national team in 2013 for the Gold Cup and World Cup Qualifiers, Beckerman still made his impact felt in the MLS. He racked up four goals and six assists in 26 appearances for the club last year, but his greatest contribution was the stability he’s brought to the squad. “He was always in the right spots and always composed on the ball,” said RSL teammate Nat Borchers after a 2-0 victory over Seattle last June. “When you have a guy like that, a leader who brings his ‘A’ game, we’re not going to lose.” All the same, orchestrating victory against Seattle in MLS competition is one thing. Rallying America against the best national squads is quite another.

This year’s U.S. squad has drawn a first-round spot in the “Group of Death” alongside perennial powers Germany and Portugal. The USMNT’s tournament kicks off next Monday against Ghana, the team that’s knocked them out of the last two World Cups. “It’s crazy because for four years you’re building up to the World Cup, and it comes down to three games,” says Beckerman. “I believe we can advance, but it’s going to be tough. Every team in the group has great players. Portugal, obviously, has Cristiano [Ronaldo]. He’s the best player in the world right now. But U.S. fans want to see us go against the best in the world. That’s what the World Cup is about.”

Beckerman knows that the USMNT is fighting on two fronts: success on the field abroad, and commanding attention at home. “It’s us against the world, and we’re trying to gain respect for U.S. soccer,” he says. “We’re trying to show we can play here, and we can beat the big boys.”

Success on the international level will help the MLS as well. Long relegated to the second tier of global professional leagues, the MLS is clearly on the rise, with high-profile US players like Clint Dempsey and Michael Bradley returning to North America after successful stints in Europe. Dempsey signed with the Seattle Sounders for nearly $7 million per year, while Bradley has a $6.5 million deal with Toronto FC. They are the beneficiaries of David Beckham’s ground-breaking move to the Los Angeles Galaxy in 2007, which ushered in the designated player rule. The regulation allows MLS franchises to compete globally for top-flight talent by signing up to three players outside of the league’s salary cap.

While multimillion-dollar contracts are far from a trend, Beckerman believes that MLS can attract more top talent. “Beckham’s going to be luring some top players from Europe. There’s already talk that Cristiano will come. If you’re offering the right amount of money, it’s going to be hard to say no.”

Still, Beckerman is adamant that these moves aren’t just about money, and that this is anything but a step back for the likes of Dempsey and Bradley. “I think those guys are going to take on big responsibilities here. They are going to be playing for championships. They’re going to have more pressure now than they did with their old teams in Europe, because of their high-profile signings, and I think that’s going to help them help the national team.” Speaking of pressure, the continual rise of soccer in the U.S. puts the onus on Beckerman and his teammates to make a good showing in the World Cup.

Twenty years after Jones, Lalas, Ramos, and Wynalda donned their famous denim kits, the US is no longer considered an interloper in the global game. Yet, despite being in the top 15 of FIFA’s world ranking for much of the last year, today's team still has much to prove. And of course a strong showing from the USMNT in Brazil is the most high-profile way for the Americans to show the world the growth of the game at home. After a decade when the makeup of the US team featured scant representation from the MLS, this year’s squad includes 10 players currently playing professionally in the States.

For Kyle Beckerman, the 2014 World Cup is the culmination of a nearly lifelong dream. It’s his long-imagined debut, but also, in all likelihood, his swansong. “By the next World Cup I’ll be 36,” says Beckerman, who’s come to terms with the fact that he only gets one shot. “There’s not many guys in the World Cup that are that age. This will be my last go. That’s why I’m doing everything I can.”

After 15 years of being the consummate team player, helping to build a league and a sport in his home country, Beckerman will finally get to don the crest of the USMNT in the World Cup. Perhaps his biggest challenge will be not trying too hard or stepping out of character in hopes of making some kind of a statement on the field. Then again, perhaps not. “Just got to keep steady, man,” he says in a characteristically chill voice. “That’s all I can do, statement or not. You want to be a good teammate. You want to help the team win games. That’s all I really care about. That’s it.”