While the biggest story from 2020 was the COVID-19 pandemic, issues with police conduct and police violence in the Black community were a huge marker of a tumultuous year as well. When you realize that many of those issues, for Black people, have been felt for decades, its important that films like Warner Bros.' Judas and the Black Messiah (hitting theaters and HBO Max on Feb. 12), which details the murder of Chairman Fred Hampton and the individual who kept tabs on him for the feds, are seen. At the very least, viewers are given a glimpse at the work of the Black Panther Party and how those issues have continued to plague cities across the country.

One of the men at the forefront of the Black Panther movement was Emory Douglas, who rose to the position of Minister of Culture within the Party, changing the face of their newspaper—The Black Panther—which ultimately changed the way information was given to the people. His images helped inform the community on everything from the Party's Ten-Point Program, to issues of police brutality, while also putting a spotlight on the oppression Black people faced. Douglas' revolutionary work has reached icon status, becoming a visual statement of the change many believe in and fight for. His works were a call to action, and continue to have an impact on the movement.

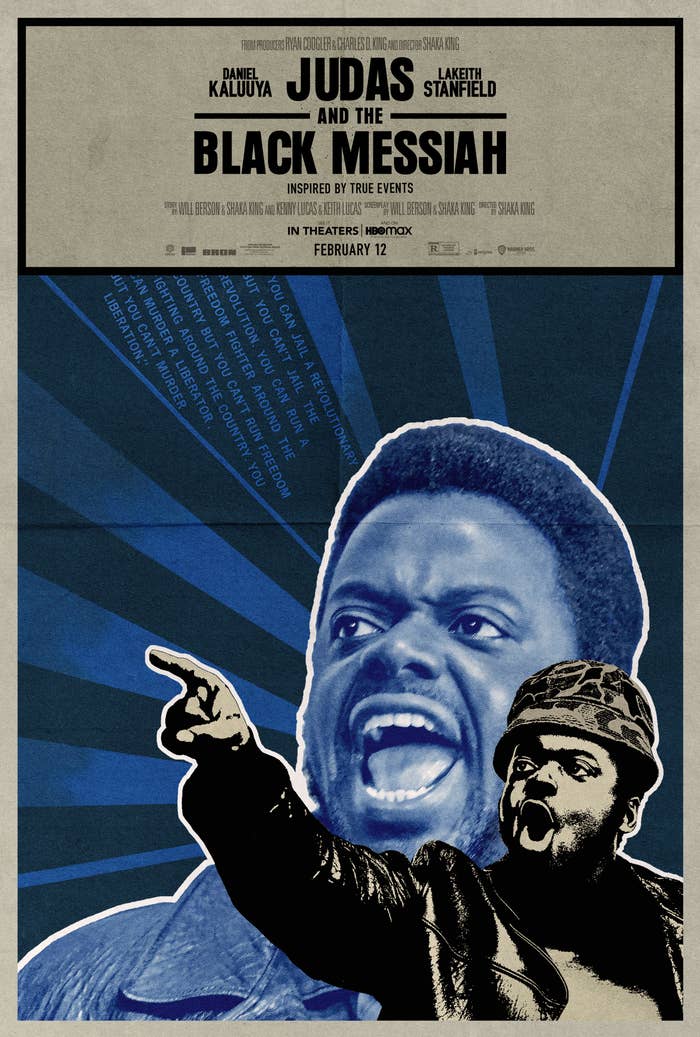

Ahead of the release of Judas and the Black Messiah, Douglas has remixed one of his works, placing Daniel Kaluuya—who portrays Chairman Fred Hampton—into the iconography of what would've been done back in the day. Douglas explains that it was Kaluuya's powerful performance, bringing Fred Hampton to life on-screen, that brought him to create this piece. "That's why I was able to remix it in [that] spirit, [because I was] inspired by that."

Douglas recalls meeting the Chairman in Chicago. "Fred would always be busy. You [would] come and connect and then he'd be gone and take care of what he had to do. The first time [we connected] was when he came out to central headquarters when they first started. Every one of their chapters or branches [that] were beginning to start up had to come to central to see what we were doing at that time, so they could go back and do that in the spirit of what geographic location where they were."

In the modern era, the path to becoming an artist can be easier. Find a copy of Photoshop, hone your skills, and you're throwing work up in the digital space in no time. Emory Douglas' path to working on the artistic side of the Black Panther movement was different, and unique. Douglas says he was interested in the world of art as a kid, but his first introduction to the world of printing (where his art would really shine) was at the age of 13, during a stint at a youth detention center. "Because I had art ambitions and desires," he explains, "I went to the printing shop. That was my first experience doing something graphic. When I got out and couple years later, I [went] to City College to take up arts. The teacher at San Francisco City College said I should take up commercial art. If I took up fine art, maybe I'd been a fine artist, but I wouldn't have known the production aspect of putting publications together and all those things. That came about taking up commercial art at City College.

"At that time," Douglas continues, "the head of the department [and] the department itself was always trying to raise the level of your artwork in the context of the Art Institute in LA. They [would] teach you drawing, printing aspect, photography, all those basic things that went into production of putting the product together, and I developed skills to the point where they was sending me out on the job assignments. On those job assignments, I began to get a better understanding. But it was more so when I worked in the community-based printing shops, learning a lot of things that could be done. You had these advertisement agencies [with] high-end equipment [that] a lot of these community printing shops did not have, but they knew how to cut the corners to get the same thing done. You learn short cuts, the limitations in the context of what you may have had to work with."

Douglas says that he was always in tune with the world of activism and how things were different for Black people in America. "In 1951, when I was about 7 years old, I remember traveling South with my Auntie and we'd catch the bus going to Oklahoma. We get off the Greyhound bus in Oklahoma City, and she grabs my hand when we going to the station, she said, 'Now we have to sit in here. You can't sit out here.' When we get there, she said, 'You got to use this bathroom in here. You can't use that bathroom out there.' And it had 'Negroes' on it." As he grew up, he recalls keeping up with the beginnings of the Civil Rights movement, coupled with the sit-ins and Free Speech movements in the San Francisco area specifically. That would turn into keeping up with international news—the unrest in South Africa and other countries across the world. Fast forward to the mid-60s, which places Emory Douglas in college, working on posters in the midst of the Black Arts West movement.

"They knew I had posters," Douglas remembers. "Some were radical. Some were moderate. It's just a broad Black arts movement of Black consciousness in many ways, so they knew of my work in that. They wanted me to do the flyer for [an] event." That put him on the radar of Amiri Baraka, the organizer of the Black Arts Movement. At the time, Douglas shares that he was "just wanting to be a part of the movement, to make change and try to make change, and wanting to learn. As you got involved and learned, you became informed." You also met people, which is how he got involved initially with the Panthers, by designing a poster for an event that would bring Malcolm X's widow Betty Shabazz to the Bay Area.

That eventually put Douglas in regular contact with instrumental Party figures like Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale fairly early on—Douglas puts it at about three-and-a-half months into the formation of the Black Panther Party, who were already generating periodicals. Douglas remembers that they were trying to recruit Eldridge Cleaver, who was writing for Ramparts Magazine, but was unable to due to his issues with the law. It was a true act of serendipity; Douglas was already community-minded, and with his background in the world of printing, and already being on Cleaver's radar, Cleaver suggested to the Panthers that Douglas could be an asset in their newspaper operation.

Douglas remembers: "Huey said, 'Well, we're going to start this paper and we want you to be the artist. You will be the revolutionary artist and eventually become the Minister of Culture'. He said, 'the paper would be about telling our story from our perspective, our point of view, it'd be like, it could criticize you on the one hand, it could praise you on the other, like a double-edged sword.'"

Douglas' work has become both iconic and important, but he doesn't put himself ahead of the message. "It wasn't just the individual. It was inspired by what we're about. [Being] against the war in Vietnam, against mass incarcerations, quality of life issues, education [and learning our] true history. That is the foundation of the spirit of the art. That's the spirit of the people."

At the age of 77, Emory Douglas is technically retired, although he does have projects he still works on, including another book of art that's currently being created. With the struggle still alive in America today, he's repurposing his influential work as a Panther for today's trials, continuing to be a voice for and of the people.