“I’m going to be brash. I’m going to be unapologetic. And I got a lot of swagger. Every detail matters to me.”

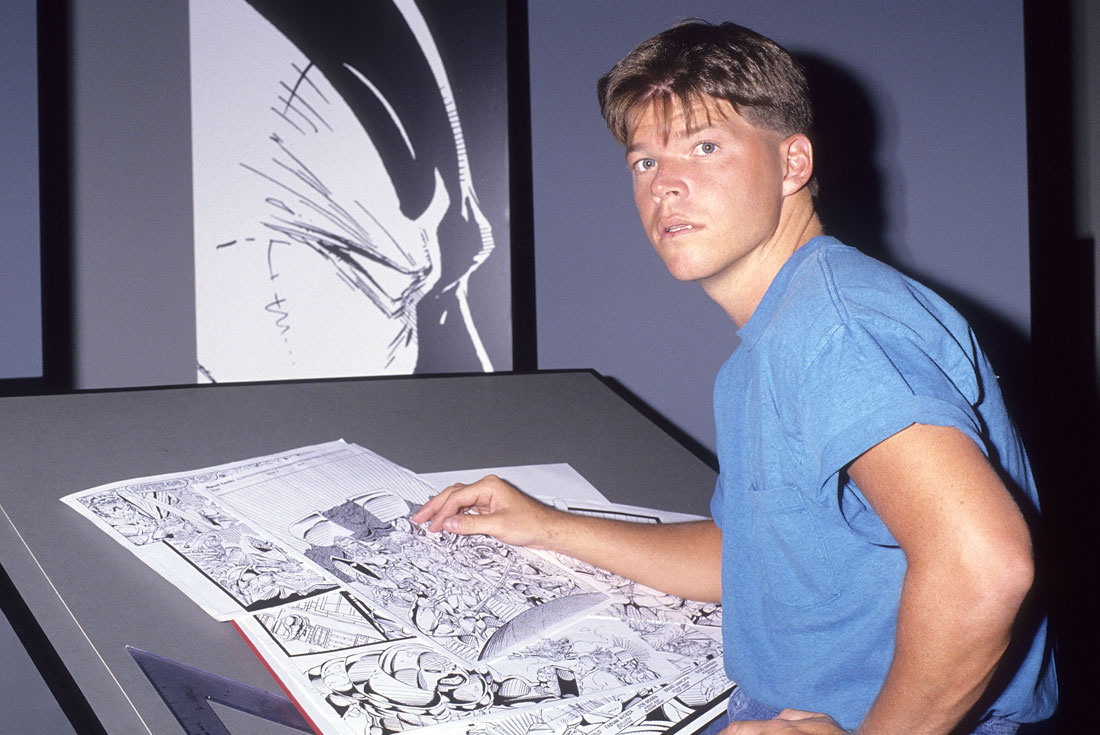

That’s how Rob Liefeld, the acclaimed comic book creator—and one of the men credited for creating Deadpool, the Merc With a Mouth set to get his own film, the first in the Marvel Cinematic Universe to earn an R-rating, on February 12—greets me. I can’t front like I wasn’t expecting it; growing up as a fan of comic books, you couldn’t open up Wizard magazine and not spot something Liefeld had created or was currently drawing. I’d seen the tales of Liefeld’s prolific progression, from a young upstart wetting his feet in the industry, to emerging as one of the creative minds behind the ‘90s dominance of Marvel’s X-Men series, to founding one of the most important publishers in comic book history, Image Comics. It’s also not hard to find articles bashing Liefeld’s signature style (pouches, everywhere!) or whispered tales of what it was like working for him. Being a goddamn professional, I was prepared for the worst: a fierce, confrontational, possibly unhinged artist.

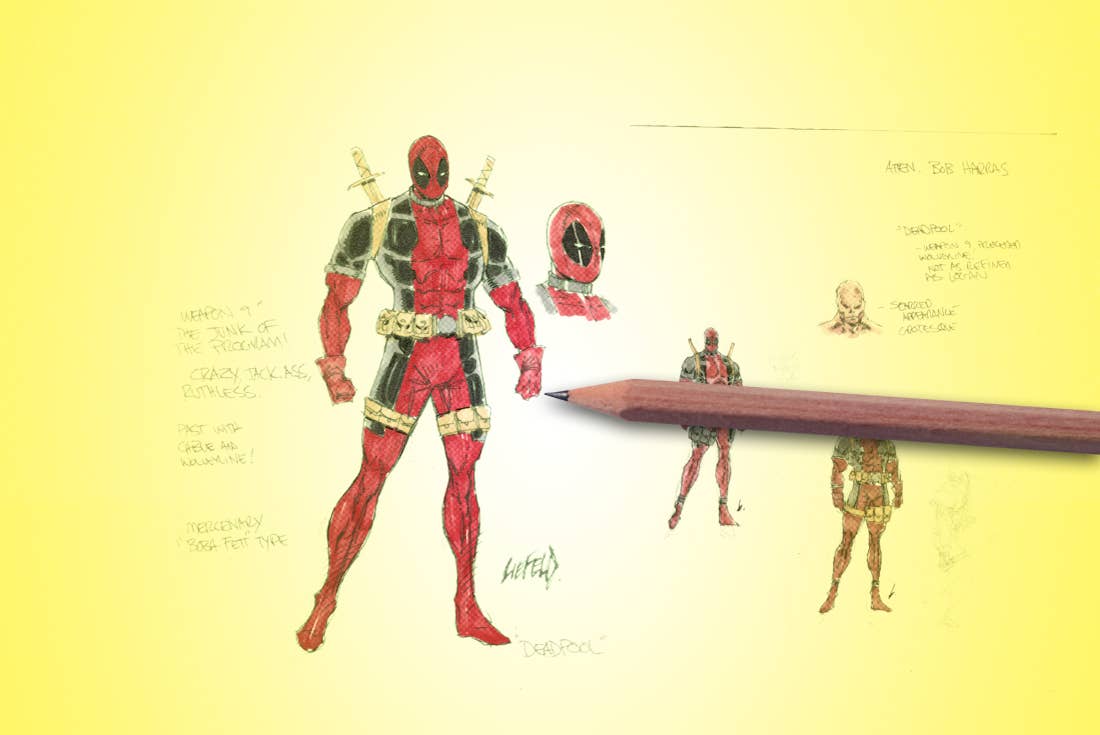

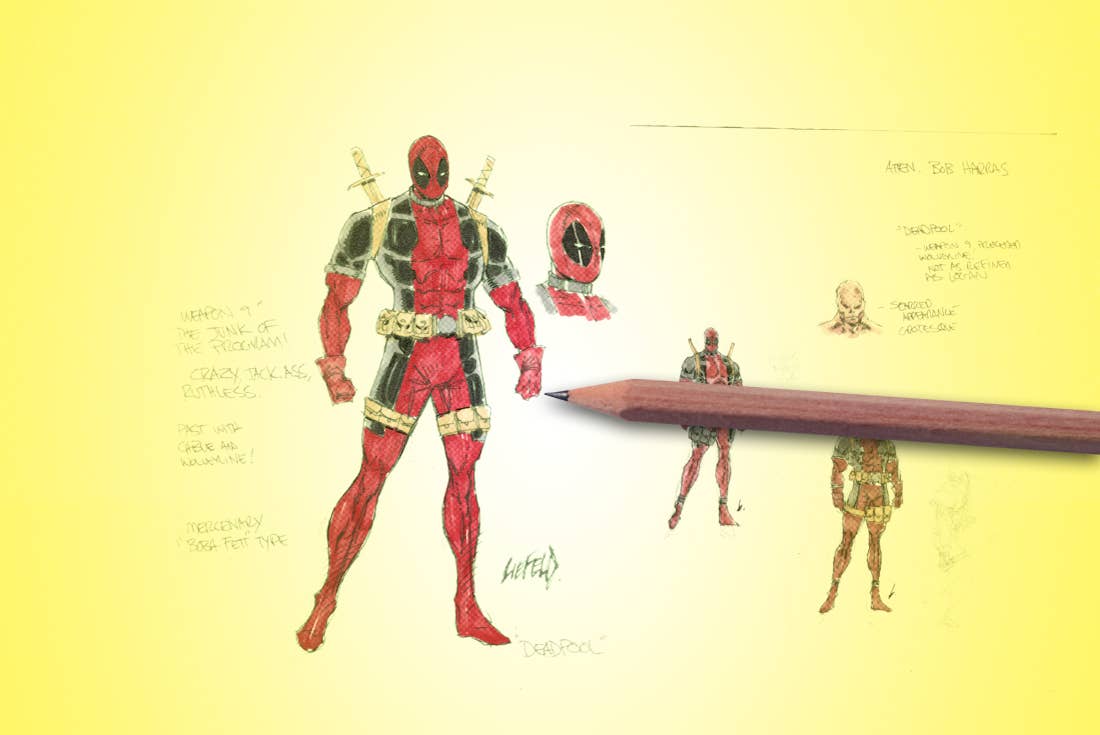

The Canadian anti-hero Deadpool, the most unpredictable character in the history of comic books, first appeared as a villain early into Rob Liefeld and Fabian Niceza’s run on Marvel’s New Mutants comic book series, and caught on VERY quickly—decimating an entire team of mutants in one issue can make that kind of statement. Over the years, a backstory developed. Deadpool was created in the same program (Weapon X) that laced Wolverine’s bones with adamantium, with Deadpool (government name Wade Wilson) being given the same healing factor that Wolverine has, making him damn-near impossible to kill (we’re talking full regeneration, even after being decapitated). He finds out that he has cancer, which pushes him to join Weapon X; he was given an experimental healing factor when he found out, and his body is horribly disfigured by the tumors and lesions, although his healing factor is working rapid fire to fight the disease. Hence the reason you always see him laced head to toe in red-and-black attire. He’s also practically insane, the kind of character that’s literally talking to himself, with two different voices sharing his headspace during a number of his comic book runs. This is a totally unkillable, tactically ready war machine that’s nuttier than squirrel shit, giving zero fucks about his life because all he wants to do is die. That’s the mindset Deadpool’s walking around with on the regular.

“I was like, 'Holy s**t,

i'm awesome.’ million sales after million sales after million sales.”

Deadpool exploded onto the comic book scene, being featured in a pair of impressive miniseries in 1993 and 1994 before finally getting his own solo book in 1997. It was over time that a number of the nuances of Deadpool’s earlier works (which included everything from a teleportation device to an all-seeing “friend” known as Blind Al) were trimmed while others (namely the ability to break the fourth wall on any occasion) were ramped all the way up, creating the finely-tuned, psychotic jokester who’s concocted some absurdly devious plan to get his man, by any means necessary. Rob Liefeld’s career has gone on a similar trajectory, with his creations and movements within the comics industry helping shape the future of the scene for years to come.

Understanding Liefeld, and the character he created, starts with understanding his beginnings as a comic book fan first. “I always had a great history of comics. I’ve been buying them since I was six years old. I was a student of the craft.” He’s the kind of guy who took that love and appreciation for the art and made his own, landing a gig at DC Comics crafting a five-issue Hawk & Dove (a superhero duo that’s been in the DC Comics universe since 1968) miniseries, and then channeling that into other opportunities. “I had gotten a lot of acclaim for giving a previously dead franchise, Hawk & Dove, a facelift,” Liefeld says, “so now I was about to do the same thing at Marvel.”

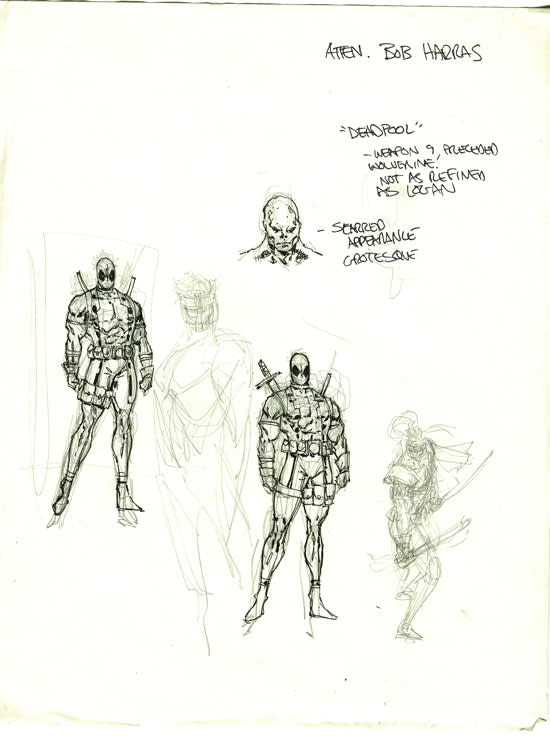

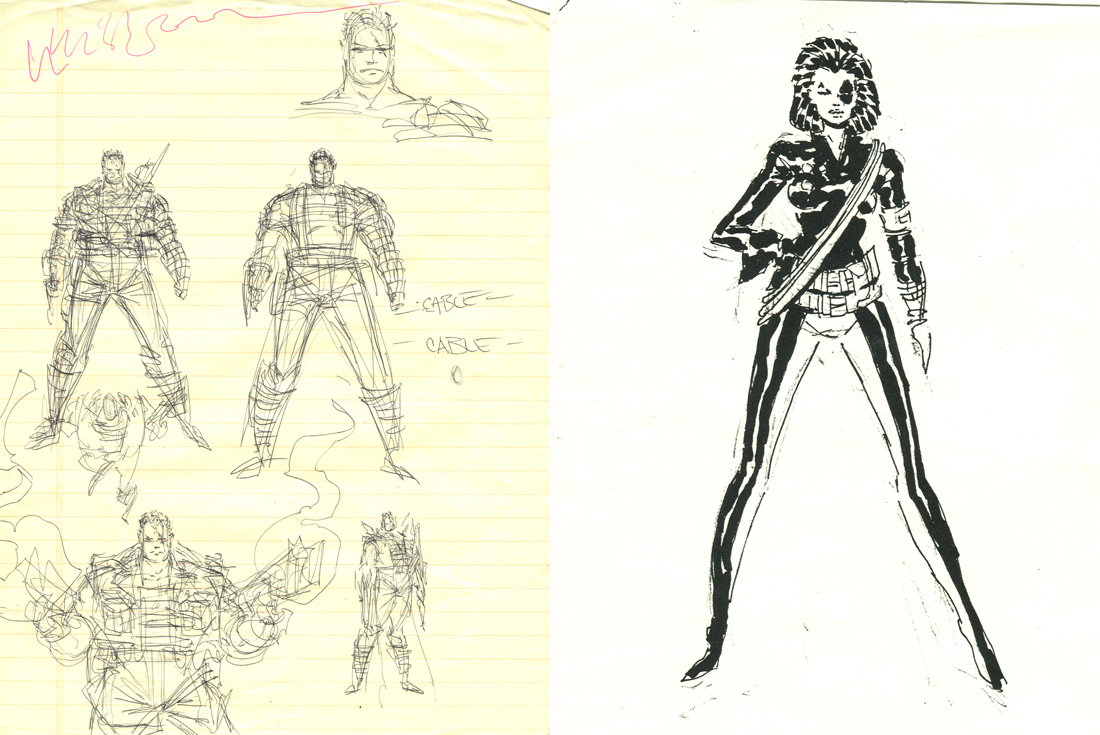

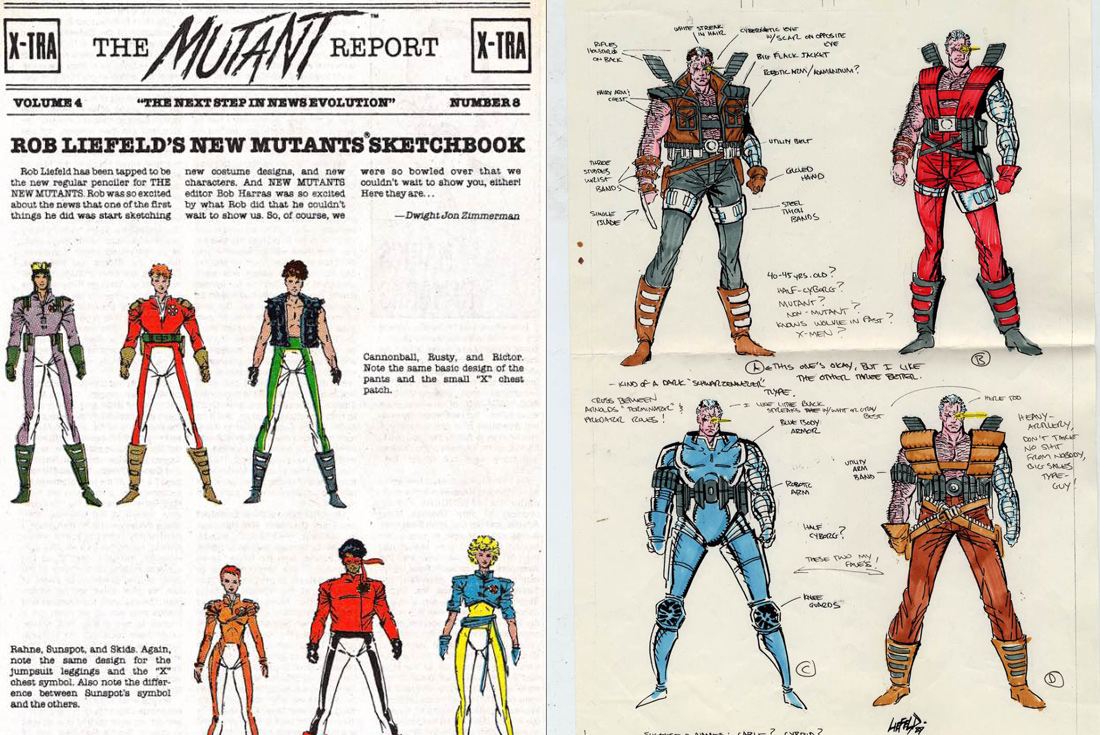

For all of Liefeld’s swagger, he isn’t wrong. When he moved to Marvel from DC in 1989 to become penciler for The Mutants, one of their lowest-selling titles, “They told me, ‘Rob, we want to make some changes. We like what you’re doing. We want this book to be infused with your energy and characters.’ They were 50 percent behind in sales to the other X-Men books at the time. That’s historically accurate.” Liefeld introduced a new character, Cable, the time-traveling future son of Cyclops. “They came to me and said, ‘We need a new teacher for the group, we need to fast forward.’ My first issue with Cable, there were 10 new characters introduced. They hadn’t had a jolt like that. Not only was there Cable, but there were nine other new villains, a Mutant Liberation Front. The success of Cable turned into an additional 300,000 copies for the book.” One of those new villains ended up being—you guessed it—Deadpool, who was introduced in New Mutants #98 in February of 1991.

Deadpool has since become his own behemoth, a now 25-year-old character that’s synonymous with the last decade of Marvel Comics’ growth. But it’s clear that, to Liefeld and many comics historians, “there’s no Deadpool without a character named Cable.”

“Cable started skyrocketing up the chart. It doesn’t take a brain surgeon to figure out that young Rob Liefeld was turning up the crank. They rewarded me by giving me the entire book to write and draw.” That book? The mighty X-Force, which starred Cable and his band of merry mutants.

The first issue of X-Force sold an unheard of five million copies back in 1991. “I was like, ‘Holy shit, I’m awesome.’ Million sales after million sales after million sales. I was kicking down doors and breaking records. That’s because my passion has always been real.” And while the Deadpool of those early X-Force days wasn’t the fully-fleshed out character that he is now, the look of Deadpool—along with being written into the history of a certain comics dynamo—helped push him from a badass who will take out an entire team of mutants to the cover of X-Force.

“Deadpool was intended, as Cable was, to be tied into Wolverine’s history,” Liefeld remembers. As a kid, he saw how the X-Men rose in popularity when they added Wolverine, and at that point he was admittedly “invested in the soap opera around Wolverine himself. He is my favorite comic book character of all space and time.” So how do you indoctrinate one of your new villains into Wolverine’s canon? You make him the Danny DeVito to Wolverine’s Arnold Schwarzenegger. “I stole that crap straight out of Twins. When they go to Danny DeVito, ‘How are they twins?’ he goes, ‘All the purity and strength went into Julius. All the crap that was left over went into what you see in the mirror every morning.’ That’s Wade Wilson. I wanted a mercenary, a bounty hunter who got in the Weapon X program, got screwed up and pissed off and sold his talents to the highest bidder. He was a jackhole.”

With the growing popularity of the X-Force comics (and Marvel’s huge line of mutant-lead titles in general) came a memorable Saturday morning X-Men cartoon and a line of action figures. And wouldn’t you know it, Deadpool and the X-Force crew were front-and-center with their own figures. “They called me and were like, our second line of X-Men toys is focused on X-Force. I was like, ‘What?’ Now I’m a toy designer.” Why Deadpool? Liefeld credits it to what one Marvel head called putting “hardware with software,” i.e. Deadpool was overflowing with all kinds of weapons. “As a kid my favorite book up until X-Men was Avengers. What does Captain America have? He has a shield. What does Thor have? He has a hammer. What does Hawkeye have? He has a bow and arrow. That’s why Cable came with weapons. That’s why Deadpool had swords and machine guns and pistols. It’s like, let’s weaponize these dudes. That’s what matters.” It might sound negligible, but when you consider that, for example, Jean Grey and Cyclops were “temple touchers” (basically, their mutant powers were always activated with a touch of their temple), they were hindered in the “cool factor” department, and that allowed these new mutants (and adjacent mutants like Deadpool) to take center stage. Fan demand was high enough to have Deadpool cover X-Force #2, and to throw the price of those early issues to enormous heights.

“At San Diego Comic Con last year, the Wednesday night before the show opened, I bought two new high graded copies for $400 each,” Liefeld tells me. “They were marketed as $500 each, but the retailers gave me a discount. I bought nine #6s and nine #5s. Again, they were going for about $500. Then they showed the trailer. I made sure [to look] the next morning. I go, ‘Oh, these comics are $1,200.’”

“My friends are like, ‘why are you giving all these characters to marvel?’

i'm like, ‘because it’s a really good deal!’”

Not too many artists understand that power, but then again, not too many artists are Liefeld, who is kissing himself for the rollout of Cable, Deadpool, and his other properties from his Marvel heyday. “Marvel is a good deal. My friends are like, ‘Why are you giving all these characters to Marvel?’ I’m like, ‘Because it’s a really good deal!’ The equity and sharing program they had in place. As a 20-year-old I was thinking retirement. I’ve already seen that Wolverine has done really well. Imagine if I had a piece of that. As a comic book artist you’re like, ‘I’ll get paid if they make this thing into a toy. Let me check that box right now. Let me sign that.’ Back in 1991 they would just send me forms and I would just fill it out. It has served. If I could go in a time machine I’d talk to Rob Liefeld and say, ‘You did good by the family.’”

Based on the success that Marvel has had with Deadpool (ranging from tons of merchandise, toys, video games and, of course, numerous comic book titles), Liefeld admits to having no problem riding the wave. “I participate in all platforms of Deadpool’s exploitation going back to 1991. People make out these corporations as being bad things. I’ve done my own stuff. I love that. I love doing it. I’ve built quite a great catalog that I own and manage. It doesn’t happen unless I do all this stuff with Marvel first. Again, I read the fine print. Every year of the last several years has been a good year. We are very happy. Here’s the deal: if I didn’t have those deals, I would have jumped off a bridge. People go, ‘Are you happy?’ I’m like, ‘Do I look sad?’ I’ve got to be honest. If I was the dumb bum who didn’t make that happen… Character participation, let’s call it that. Let’s call it that. That’s a good thing. Royalties are good.”

Some might say that getting paid off your hard work is amazing, but any creative person knows that it’s never that easy—sometimes it becomes deeper than getting paid, especially when we’re talking about who owns intellectual property. When Liefeld says he’s done his own stuff, he’s referring to his creator-owned series, of which he has many (including fan favorites like Youngblood, Supreme, and Prophet). For creatives in the comics industry, it’s not just about enhancing the pillars upon which said publisher has built their empire; the hope is that you can create exciting new characters. And get the credit for them—that’s where things get dicey. While creators might get a solid paycheck from one of the “Big Two,” they aren’t always given the proper recognition. Any characters they create often become the property of Marvel or DC Comics, which doesn’t sound terrible, until you look at the story of a guy like Jack Kirby. Kirby was one of the most prolific artists in the industry, with a hand in Captain America and the Fantastic Four, the X-Men, and the Hulk, but ultimately he got discouraged, and sued Marvel Comics for proper compensation for his successful franchises. Kirby’s suit didn’t help him find any justice—a judge ruled that his freelance work didn’t entitle him to retain copyright.

It’s a tough situation for anyone to be in; do you stick with Marvel, where you can potentially get paid very well for characters that could earn Marvel billions of dollars, or do you jump ship and invest in yourself? For Liefeld, as well as a group of artists who were behind the highest-selling Marvel comics of 1991 (including Todd McFarlane, Jim Lee, and Erik Larsen), it was time to strike out on their own. So in 1992, the crew helped found Image Comics with the idea of creating—and owning—their own characters and series. Even if you aren’t a comic book nerd, you’ve no doubt heard of The Walking Dead and Spawn, two fine examples of Image series that impacted the worlds of television and movies, respectively. It was the spirit of guys like Rob Liefeld, coupled with the “fuck the system” attitude of Todd McFarlane, that turned these rock star artists into men who caused a cataclysmic shift in the way creators approach their craft, even if Liefeld and Jim Lee ended up going back to Marvel in 1996 in an attempt to redefine some of the company's major properties, like Captain America and The Avengers.

Liefeld and Lee’s return was a move that questioned what system is best suited to the creation of quality comic books. Do creators benefit more from the establishment, developing careers through the machinery of the major publishers? Or is it best to have the option of working for a Marvel or DC while cultivating independent for distribution through a publiser like Image? Liefeld, the seasoned vet who’s played on both sides of the creative fence, has an interesting take on the phenomenon: “My system is great, but the system now is great because of what we did in the ‘90s.” Liefeld and the co-founders of Image rejected the industry, changing the future of comic books for years to come, for the better.

Sadly, after four years of being a part of Image, Liefeld resigned from his position in September of 1996. His choices weren’t sitting well with his partners, and he filed his resignation just before he was set to be voted out. That same year, he moved his Extreme Studios creations to Awesome Comics, and when that company went under in 2000, Liefeld returned to Marvel, working on penciling and cover art for both the Cable and X-Force series, and collaborating with Deadpool co-creator Fabian Niceza on the critically-acclaimed Cable and Deadpool series, and eventually penciling the first nine issues of the 2010 series Deadpool Corps.

With the comic book boom of the 1990s long gone, Liefeld has yet to achieve the same success again, although Image Comics grew in stature, adding successful series like The Walking Dead to its stable, effectively setting new trends for the future of comics and how they impact mainstream media.

This new era opened the doors for darker, less-cartoonish characters to blow up outside of the panels of your favorite comic books. Liefeld sees that tone as a clincher, the thing that’s going to separate Deadpool from what DC’s done on The CW with The Flash and Arrow. “I like all my entertainment adult,” he says. “The only thing[s] I watch are on Showtime, Netflix, HBO, or Starz. Once you see the adult stuff, you don’t want to see the kid stuff. I think The CW is made for kids and that’s great, [but] the reason why Walking Dead does six times that number is because it’s more adult. It can make as much as it can on subscription cable service, not paid, but a basic cable. It’s very violent, very gory, there’s more adult content. I do believe Deadpool is going to have a huge, huge impact in terms of people going, ‘I want that now. I want that.’”

It’s something that Liefeld—and hardcore Deadpool fans—have wanted for a long time: a hard-R rating. In the current comic book film climate, most movie adaptations are PG or PG-13, ratings that would completely compromise the ultraviolent, ultra-lewd tone of the Deadpool comics. The rating is a win for fans, and is a key to why Liefeld feels that Deadpool will be a gamechanger. “This year,” Liefeld says, “is going to show, more than ever, that the product has to change.” Deadpool fans shrieked in horror at Ryan Reynolds’ first portrayal of the Merc With a Mouth in X-Men Origins: Wolverine; the first nine or 10 minutes of the film gave us the motormouth as he’s portrayed in the comics, but by the end of the film, Deadpool was literally muted. The fight to bring Liefeld’s character to the silver screen had been rumored about since as early as 2000, with plans to spin Wade Wilson off from the Wolverine film early into its production. It wasn’t until 2010 that Liefeld actually caught wind of the new project. “Tim Miller called me five years ago and he said, ‘Rob, I bought your Deadpool comics, I bought this as a kid,’ and was like, ‘I’m the director of Deadpool.’” It isn’t a kids film by any means; Liefeld, who is a father and has a nephew, actually had to tell the parents of his sons’ friends that they should not be taking their kids to see the film. Although he’s no fool: “They are going to find a way like I did with R-rated movies. My nephew already said, ‘Uncle Rob, I’m seeing it.’”

Deadpool’s been buzzing on the Internet for months, and it’s about to blow up Hollywood. Now, with rumors that a sequel is practically in the bag, it’s hard to resist asking Liefeld what’s next for the franchise. When I do, Liefeld resists the question, quipping slyly that “when a guy like me who talks all the time tells you he can’t talk, that’s serious.”

His silence speaks volumes for Deadpool’s future. Liefeld doesn’t hesitate to thank Ryan Reynolds, Tim Miller, and everyone who made this film possible. He also brings up his patience a few times—he’s sat for 25 years and watched Deadpool rise from the sidelines to becoming a strong contender for best superhero film of 2016. For all of the brashness, all the swagger, Liefeld’s talent lies in setting up his shot. He’s been waiting for the right time to strike, and on the eve of Deadpool’s release, he’s ready to pull the trigger.