The British film industry doesn’t make movies for kids from South London. There are plenty of British films about working-class people, but those films aren’t actually for working-class people. Yet, in the mid-2000s, a gritty little film called Kidulthood, about a group of kids given a day off school following a classmate’s suicide, changed all of this. It kicked off a wave of British hood movies and the film’s young upstart distributor, Revolver Entertainment, was quick to make the most of that trend.

Films like Anuvahood, Sket, Shank and Ill Manors brought grime stars and estate kids to the screen, in films actually made by and for the youth of the time. While not all these films were ‘good’ in the traditional sense, they were fast, exciting and a welcome break from the stuffy film establishment that was churning out things like The King’s Speech. If nothing else, they gave us a far more accurate London than the one depicted in Love Actually. Revolver Entertainment’s flame burned brightly but briefly, winning awards and raking in the dough, but crashed into administration by 2013, amidst flops, tumbling DVD sales and rumours of unsustainable decadence. But it seemed like a hell of a ride.

When I went there on a very rainy afternoon in November 2014, there was not much to see at Princes Place. A cul-de-sac in West London’s fancy Holland Park, it was all expensive houses and some sweet kids messing about with bikes trying to avoid the rain. Five years ago, though, this was home to Revolver HQ.

Back then, by all accounts, they lived like ballers. The office was decked out with a basketball court, fancy coffee machines, and even their own screening room.

Back then, by all accounts, they lived like ballers. The office was decked out with a basketball court, fancy coffee machines, and even their own screening room. The location seemed rather fitting for Revolver. Not only is it only little more than a stones throw away from the (much rougher) Ladbroke Grove setting of Kidulthood, it’s also notably away from the media hub of Soho and the rest of the British film industry. Revolver were doing things their own way, not playing by the rules, so why should they hang around with everyone else? Holland Park is a very posh area—house prices are in the millions and it’s home to several national embassies—and the idea of the rowdy kids that made Sket and Shank moving in, building their own MTV Cribs-worthy base, just seemed too perfect. Was it a sensible idea? Was it sustainable? Probably not. It was almost certainly, at least a small part of their decline.

1.

Started by entrepreneur Justin Marciano in 1997 with supposedly just £1,000 of his own capital, Revolver Entertainment had ignoble beginnings. They specialised in putting out straight-to-video products, often motorbike videos and softcore porn. Highlights included Snoop Dogg’s porn production Doggystyle, a compilation of Comical Ali (the briefly-viral Iraqi spokesman), and Thumb Wars, a lame Star Wars parody starring thumbs with eyes painted on.

They specialised in putting out straight-to-video products. Highlights included Snoop Dogg’s porn production Doggystyle.

They were the sort of things you buy as a Secret Santa present for people you don’t really know, or pick up stoned at 3am in ASDA. If it sounds like I’m being snide, I’m really not—there’s definitely a market for these things and they did good business. Darrin’s Dance Grooves, with Britney and NSYNC choreographer Darrin Henson, shifted over a hundred thousand units in 2002. This success led to their first cinema release in 2004 (surfing documentary Billabong Odyssey), and quickly they were releasing respectable, critically acclaimed films like Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man and Terry Gilliam’s Tideland.

2.

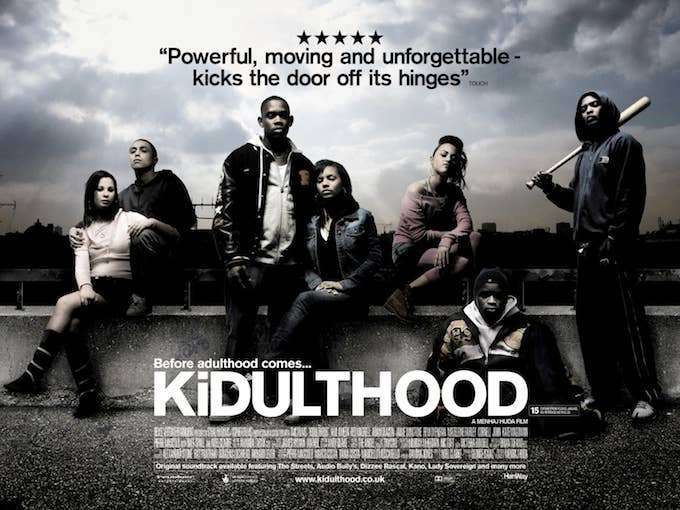

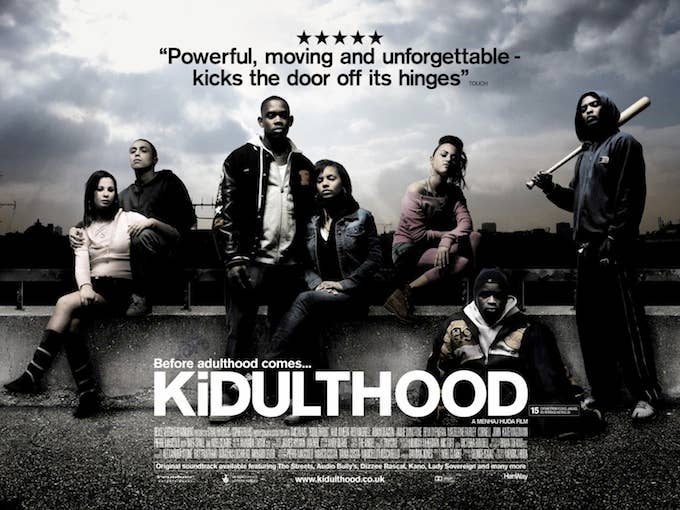

Yet it was the release of Kidulthood in 2006 that changed everything. There were already a couple of British attempts to make a Boyz N The Hood-style hood movie, like 2004’s Bullet Boy with Ashley Waters. But Kidulthood was a kick in the teeth compared to those films. Written by Noel Clarke, and featuring early appearances from the likes of Jamie Winstone, Nicholas Hoult, Adam Deacon and Rafe Spall, it pulled no punches in showing teenagers fighting, fucking and getting fucked up. It really felt like the first time since early Danny Boyle that British youth culture was actually up on screen. The film did ok financially (and was a hit on DVD), but it was its manic energy and roaring grime soundtrack that really made it stand out. Guardian ran think-pieces on it and The Sun called it a “happy-slapping” film. To promote the DVD, Revolver hired a 40ft billboard near Earl’s Court, with the faces of Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, and the rest of the then-cabinet Photoshopped over the cast. Blair himself was turned into Noel Clarke’s villain of the piece.

In a rather high-minded statement, the company said that they wanted the billboard “to encourage and provoke debate, not only about the content of the film, but about the ways in which the Government have dealt with these problems in the eight years since they came to power, to ask how they are making their policy relevant to all young people.” That might not really stand up to much scrutiny, but it definitely helped the film capture the zeitgeist. The image made its way into multiple broadsheets and tabloids, and David Cameron even referenced the film in his notorious ‘hug a hoodie’ speech later that year.

As they entered the second half of the decade, Revolver were flying; French thriller Tell No One was a breakthrough smash, and they also distributed Oscar-winning documentary Taxi To The Dark Side. And there was also the Danny Dyer/50 Cent opus Dead Man Running, produced by none other than Rio Ferdinand and Ashley Cole. But the next step would come in 2009, with the formation of their own production arm: Gunslinger Films. Revolver had already produced a few straight-to-video products, mostly things like Danny Dyer’s Football Foul-Ups. But after missing out on the sequel to Kidulthood, Gunslinger meant that they could produce their films targeted at the UK youth market, with low (under £1 million) budgets and keep hold of the international distribution rights. Ultimately, it proved to be a step too far for the upstart distributor, but for a brief while, Revolver created probably the first British production studio to have its own real identity since Hammer Horror or Ealing Studios.

3.

Their first self-produced release was 2010’s Shank, a very British take on the classic '70s gang movie The Warriors. Set in a future (2015) London, it starred Bashy, Adam Deacon and Skins’ Kaya Scodelario as members of teen gangs battling in a capital gone to shit. The futuristic, Mad Max-inspired setting makes it seem a million miles away from Kidulthood, but it followed much of the same gameplan. Again, it’s about group of multi-ethnic London teenagers forced to fend for themselves, dabbling in knife violence, fighting and other stuff to scare the Daily Mail. Shank did average business, and was reasonably entertaining, but it was Gunslinger’s next production that would really give Revolver their moment in the sun.

You know a type of film has hit critical mass when it gets a wacky parody made out of it. And in the grand tradition of Naked Gun, Hot Shots and Scary Movie, early 2011 saw the release of the first British hood spoof Anuvahood, co-written, co-directed and starring Adam Deacon. From its gaudy pink and yellow poster to the fact that it looks like an even worse version of those already terrible Epic/Date/Disaster Movies, it’s easy to expect it to be awful. The critics hated it and it’s currently got 15% on Rotten Tomatoes.

4.

But Anuvahood hit its audience perfectly. It made over £2 million at the box office, broke all of Revolver’s previous records and continued to do well on DVD. Again, it was another example of Revolver’s innovative marketing, with aggressive social media getting thousands of fans months before the release, way back before Facebook was de rigueur for film marketing.

They even gave away packets of Fruitella and Chicken Cottage vouchers for every few thousand fans they got (both heavily featured in the story). The film itself is also far more interesting that its critical reception would suggest. It’s not necessarily ‘good’—it’s very cheap and the jokes are obvious—but it’s the sort of film that will be a fascinating time capsule in 20 years. It’s a world rarely captured on film, and if it ever is, it’s in deadly serious ponderings about gun crime or in sleazy exploitative Danny Dyer schlock. It’s so unusual to see people who live on an estate to be shown having a good time, without any sort of moralising behind it. It features cameos from grime stars and black British comedians that the mainstream had never heard of, but also sitcom stalwarts like Linda Robinson and Perry Benson. It’s a strange, fascinating experience.

5.

Things would never hit the heights of Anuvahood again for Revolver. The next Gunslinger production to hit cinemas was Sket, a rather clichéd girl gang story that failed to grab the audience. Maybe the female focus alienated the teenage boys that loved Kidulthood and Anuvahood. Or maybe naming the film after a then-still rather obscure piece of slang confused people (way before Rio Ferdinand popularised it on Twitter). The distributor continued on, maintaining their schizophrenic approach of mixing up similar low-rent British (but less urban) crime cheapies like The Veteran and Turnout, alongside broadsheet-approved fare such as Snowtown and The Imposter.

Gunslinger’s next production was Ill Manors, the directorial debut of Plan B, and it seemed like it should have been more of a guaranteed hit. Fresh off his Strickland Banks crossover success, Ben Drew was now a mainstream star and it was being tipped as the British 8 Mile. Yet the final film turned out to be nearly 2 hours (allegedly cut down from much longer) of non-linear, overly-artistic vignettes of London’s urban depression. In a lot of ways, it’s the best film Revolver ever produced—the rapped character introductions by Plan B are thrilling and it doesn’t suggest there are any easy answers to the city’s problems. Yet it’s so hard going and relentlessly bleak that it was never going to be the mainstream hit Revolver hoped it would be. It wasn’t an expensive film to make—made under £100,000 as part of a low-budget Film London initiative—but it performed well under what was expected of it, and it felt like the beginning of the end for Revolver.

6.

In March 2013, Revolver’s Holland Park offices shut their doors for good, and the company fell into administration a month later. The reasons for the collapse were not clear-cut. While they’d continued to have some successes, the disappointing performance of Ill Manors, as well as another homegrown title Payback Season (starring Adam Deacon as a Premiership footballer and featuring the acting debut of Geoff Hurst!) surely played a part. Overall declining DVD sales also greatly harmed them, as Netflix and piracy both ate into the secondary market that was so important for the sort of films Revolver released. There’s also suggestions that the company didn’t spend their money in the wisest way—an unnamed freelancer told The Daily Star (of all people) that “they just had more outgoings than incomings and overspent. They’d throw great parties and just spent far too much. The offices were like something out of Hollywood.”

So what’s the legacy of Revolver Entertainment, and their oeuvre of hood movies?

Ashley Clark, a journalist and film programmer who’s written about black British film for the BFI, has mixed feelings on them: “Though some are certainly more successful than others, they were all pretty cheaply made, commendably energetic, and featured cash-in soundtracks with popular, of-the-moment music—grime, R&B, whatever—and liberal lashings of violence and unhappy sex. The most interesting thing about them, for me, is that they all seemed to be anticipating, in some respect, the riots that erupted across the country in 2011: that sense of nihilism, social discord, and a complete lack of empathy/understanding between generations, and between youth authority figures.”

With the likes of Noel Clarke and Adam Deacon already in their 30s, Revolver’s films already almost feel like part of a youth culture that may have already past. Maybe someday they’ll gain a cult following from future generations, divorced from the culture that created them, like Blaxploitation or Hammer Horror. And much like Blaxploitation, people continue to debate whether they were revolutionary anti-establishment works or just perpetuated the same old stereotypes. But regardless, they’ll live on as fascinating snapshots of London and Britain in the early 21st century.